In-depth Q&A: How will the UK’s ‘heat and buildings strategy’ help achieve net-zero?

Josh Gabbatiss

10.20.21Josh Gabbatiss

20.10.2021 | 8:39amA goal to eliminate new fossil-fuel boilers from 2035 is one of the stand-out pledges in the UK’s highly anticipated heat and buildings strategy.

Following months of delays and false starts, the government has finally released details of how it intends to cut emissions from the nation’s building stock.

It contains information about £3.9bn worth of funds to support low-emissions homes, including new grants to support the replacement of gas boilers with cleaner alternatives.

However, it also comes only seven months after the government scrapped its £1.5bn “green homes grant”. And the new money falls far short of the £9.2bn that the Conservative party said it would spend on energy efficiency by 2030 in its 2019 election manifesto.

The strategy comes down firmly in favour of electric heat pumps, subject to “expected” cost declines, while a decision on the widespread use of hydrogen gas in heating systems has been delayed until 2026.

In this article, Carbon Brief assesses the 202-page strategy and how effective it will be in helping the UK achieve its legally binding target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

- Why does the UK need a heat and buildings strategy?

- Is there any new support to help people insulate their homes?

- Is the government banning and ‘ripping out’ gas boilers?

- How will the government support the expansion of heat pumps?

- How will it keep low-emissions heating costs down?

Why does the UK need a heat and buildings strategy?

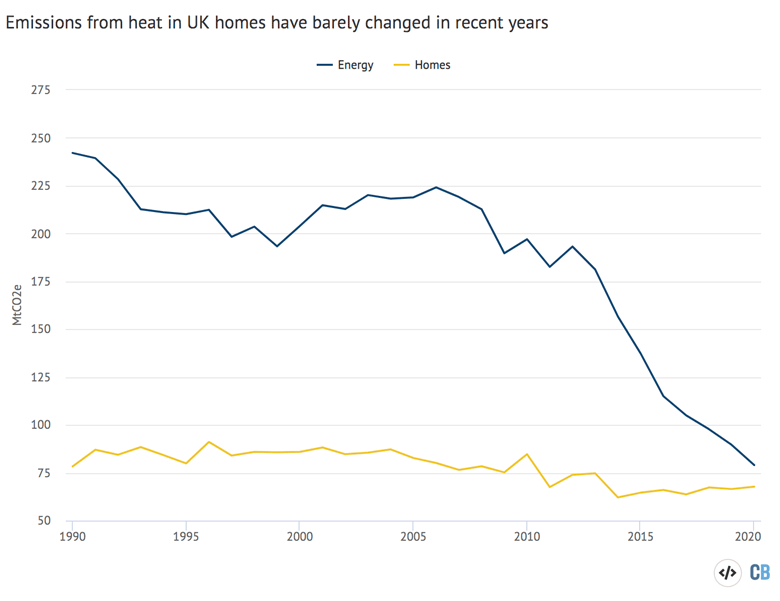

Heating buildings, largely with natural gas, accounts for nearly a quarter of UK emissions. The majority of these emissions come from people’s homes.

While houses are now powered by increasingly clean electricity, much slower progress has been made in decarbonising their heating systems. Emissions are only 14% below 1990 levels and have been increasing slowly in recent years.

The UK has also frequently been described as having among the oldest and least energy-efficient housing in Europe.

Around 19m homes across the country – two-thirds of the total – are ranked in the bottom rung for energy efficiency, with Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) ratings of D or worse.

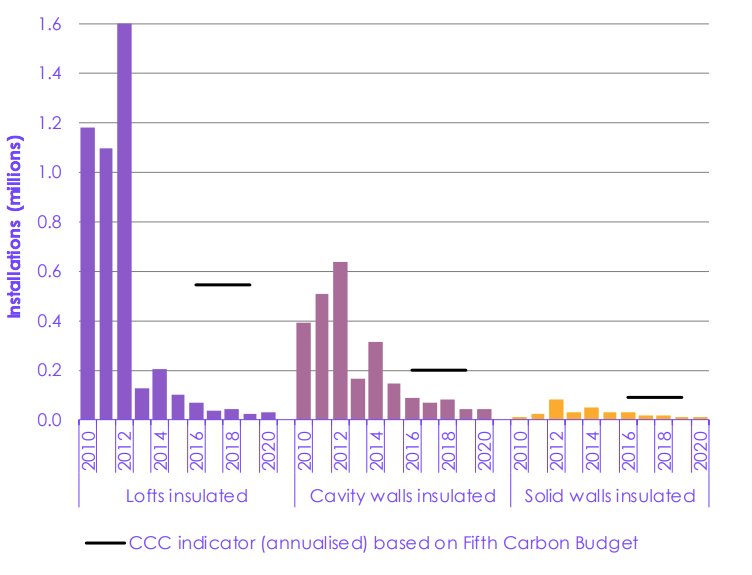

Progress in this area has been slow for the past decade of Conservative rule.

After David Cameron reportedly urged aides to “get rid of the green crap” in 2013 and as his government dialled back spending on energy efficiency, rates of home insulation collapsed. This can be seen in the chart below.

A plan for improving the energy standards of homes and decarbonising heating is, therefore, widely seen as a top priority as the government develops its overarching plan for reaching net-zero by 2050.

The heat and buildings strategy, which has been in the works for two years, is one of many climate-related plans that have faced long delays, following the transport, hydrogen and industrial decarbonisation strategies, among others. The document has been repeatedly – and selectively – briefed to the press before having its publication date pushed back further.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC), the UK government’s climate advisers, have described delays in government planning as “disappointing”, as they have contributed to the growing gap between the UK’s legally binding climate goals and the policies in place to meet them.

Some details of building decarbonisation were announced last year in the government’s energy white paper and prime minister Boris Johnson’s 10-point plan which pledged, among other things, to install 600,000 heat pumps every year by 2028, but were light on detail.

The long wait for the heat and buildings strategy, which is the last sector-specific net-zero plan expected this year, reflects the sensitive nature of the topic.

Unlike other key areas of the economy, such as heavy industry or the power sector, this aspect of net-zero planning will require homeowners to make substantial changes to their properties. As such, it has been met with considerable pushback from sections of the press, as well as a handful of backbench Conservative MPs and trade unionists.

In particular, tabloids and right-wing publications reporting on selectively leaked parts of the plan have warned of gas boilers being “ripped out” of people’s homes, more expensive mortgages for inefficient homes and rising energy bills for poor families, if levies are placed on gas. The Daily Express even launched a campaign to “save our boilers”.

Today’s Times frontpage is reporting govt plans to (consult on & then maybe) include heat & transport fuel in the UK’s emissions trading scheme

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) July 2, 2021

A few thoughts

1/https://t.co/OYt4zGrQLI pic.twitter.com/CaZY3EU1OC

This kind of messaging has, in turn, faced strong pushback, summarised in a statement by Juliet Phillips, a senior policy advisor at thinktank E3G, who described the heat and buildings strategy as “accelerating progress towards greener homes – reducing energy bills, creating warmer and healthier houses, and boosting green jobs across the country”.

Buildings are expected to be one of the more expensive areas of climate policy in the coming years and one that will require significant public funding. However, many have argued that the benefits significantly outweigh the costs.

The Construction Leadership Council, an industry group, wrote to business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng in May to say upgrading “the UK’s draughty homes to low-carbon standards would cost the government only £5bn within the next four years and would create 100,000 jobs, cut people’s energy bills, increase tax revenue and bring tens of billions in economic benefits”.

Meanwhile, climate protesters from Insulate Britain have made headlines in the weeks leading up to the strategy’s launch by obstructing traffic in the name of awareness-raising around the nation’s leaky homes.

While the UK’s major plan for home-efficiency improvements, the green homes grant, was scrapped earlier this year due to mismanagement, other European nations have injected billions into similar schemes to boost their economies following Covid-19.

Moreover, the CCC’s net-zero advice concludes that home-efficiency improvements could more than offset the increase in climate policy costs on people’s bills out to 2030.

The strategy itself received a mixed response, with many concerned over the ambition – and particularly the money – being put forward by the government. Nevertheless, others, such as Phillips, emphasised the importance of the document and said it was now “up to the Treasury to back this plan with a comprehensive investment package”.

Now, if these proposals are agreed it would be transformative for the sector — creating robust incentives to create new offers that work for consumers.

— guynewey (@guynewey) October 19, 2021

The announcements themselves demonstrate a serious commitment to action in one of the toughest areas politically….

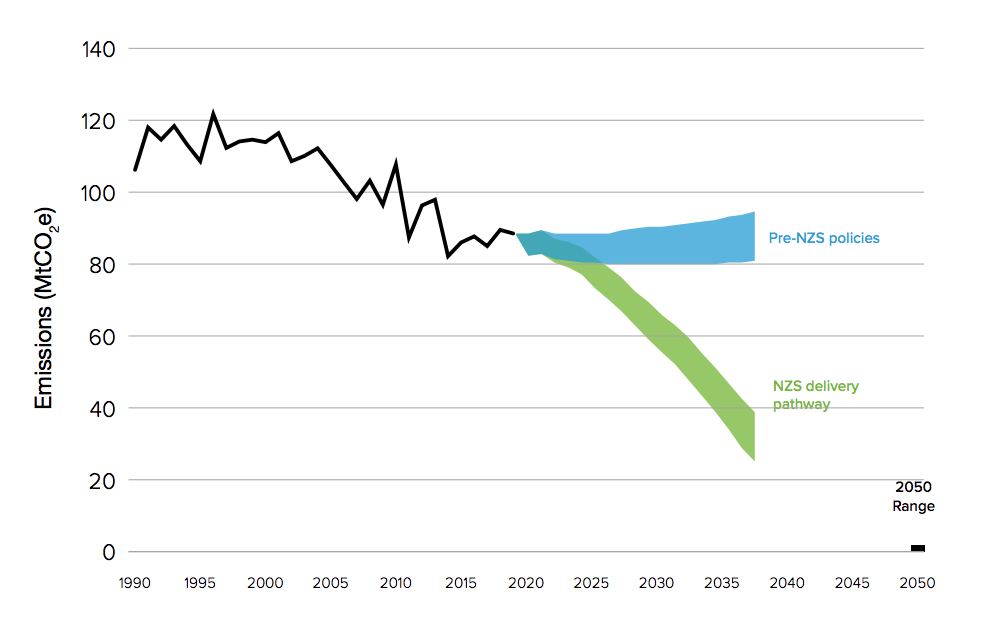

The chart below, from the government’s net-zero strategy, shows the significant shift in projected trajectory for emissions from building heat in a scenario with (green) the government’s net-zero policies compared to one without them (blue).

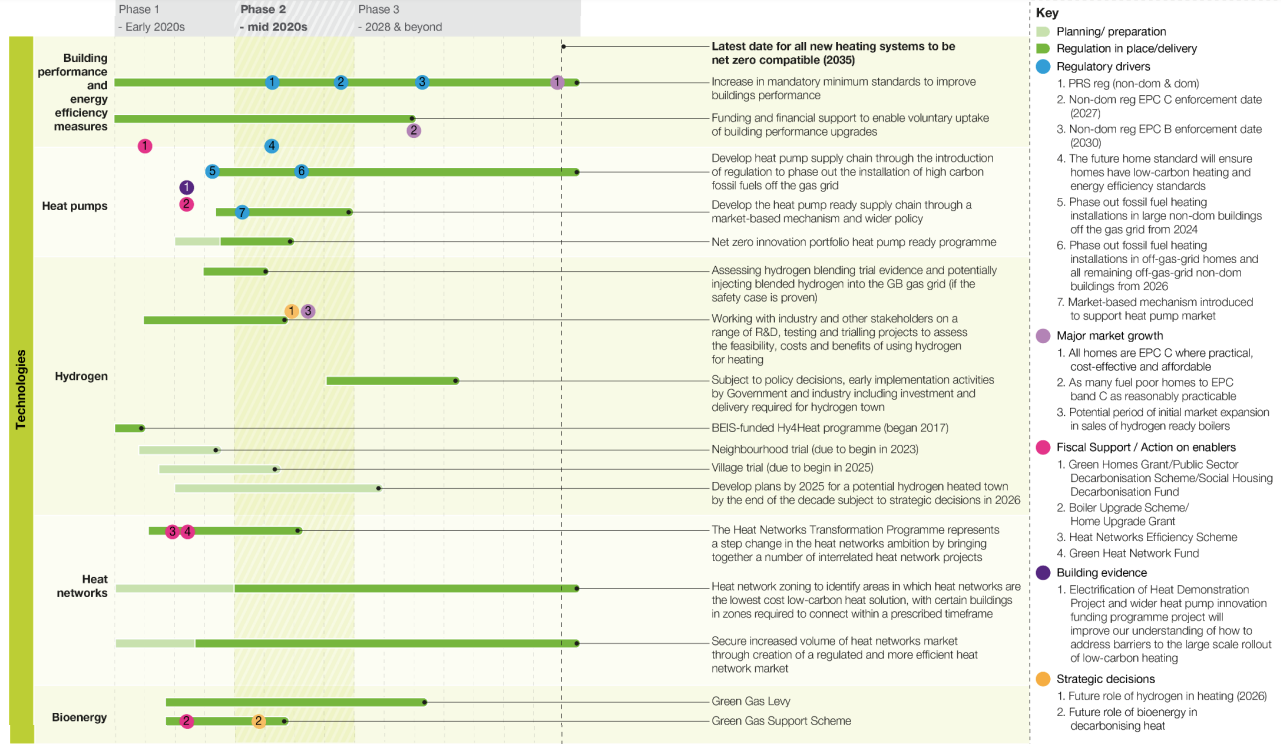

The timeline below shows the details of these various policies, including lines showing when preparatory stages are taking place (light green) and when the full regulation or delivery stages are expected to begin (dark green).

Various other documents were published alongside the strategy including consultations on the use of a market mechanism to mandate heat pump uptake and on phasing out fossil-fuel heating in homes and businesses that are not connected to the gas grid and, therefore, currently use oil or even coal for heating.

Is there any new support to help people insulate their homes?

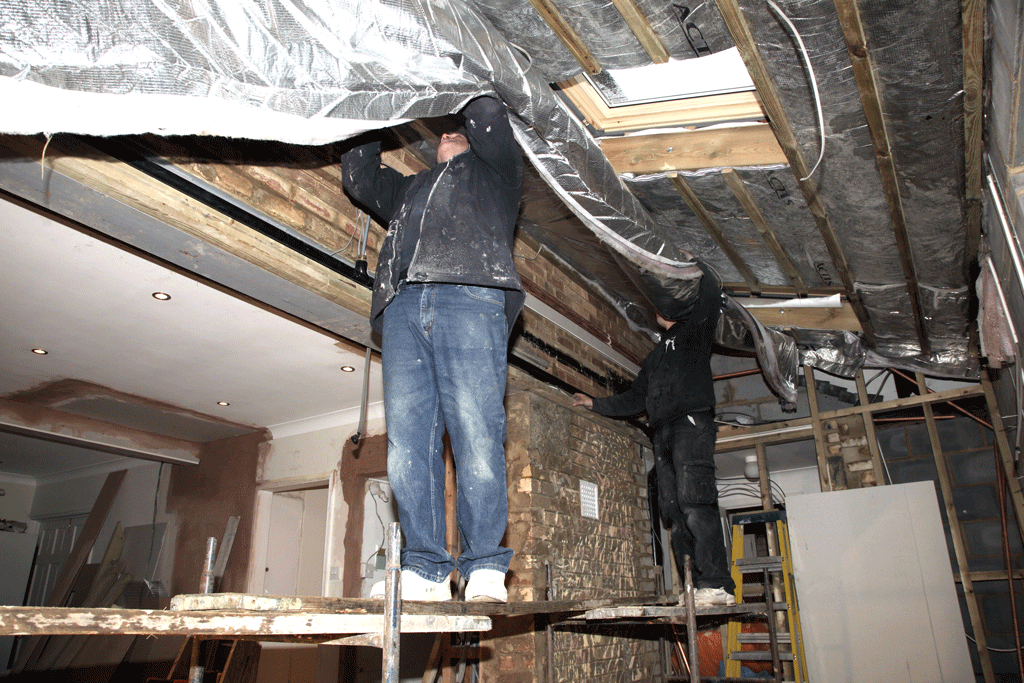

The opening section of the heat and buildings strategy states that the “journey to net-zero buildings starts with better energy performance”, emphasising the importance of a “fabric-first approach” that focuses on improving the efficiency of walls and lofts before replacing heating systems.

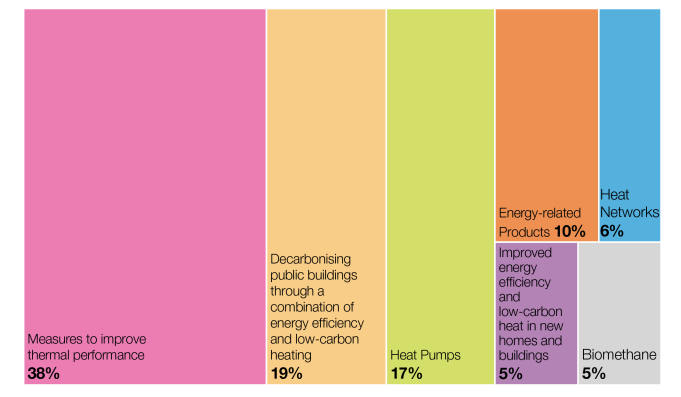

The chart below highlights the importance of these activities in the government’s policies and projections for cutting emissions by 2030.

In total, 38% of cuts over the next decade are expected to come from improvements to the thermal performance in existing homes, with an additional 24% involving such improvements in public buildings and new homes.

by 2030, by technology type. Source: BEIS.

Nevertheless, compared to the headline-grabbing commitments and funding towards heat pumps, energy efficiency receives less attention in the strategy.

Dr Jan Rosenow, director of European programmes at the Regulatory Assistance Project, tells Carbon Brief that while a focus on efficiency measures is “in the rhetoric” there are “no substantive policy announcements in there on energy efficiency that I could pick up”. Instead, he said the strategy mainly reiterated pre-existing policies.

One relevant point that has been picked up in news coverage is a proposal, following a consultation that ended in February, to set a target for mortgage lenders to reach a certain energy efficiency standard – EPC band C – across their portfolio by 2030.

Costs would therefore be passed on to new homeowners, who may then make money back through cheaper bills. However, the plan has come under fire for potentially harming first time buyers.

There is also some additional funding for the existing home upgrade grant (HUG) and social housing decarbonisation fund (SHDF), both of which address energy performance in low-income households. They received boosts of £950m and £800m, respectively.

Nevertheless, the government is now at risk of leaving not only a policy gap to achieving net-zero, but also a funding gap, with experts warning that not enough public finance is being directed towards these kinds of schemes.

In March, the government decided to cancel its flagship green homes grant, initially announced as the key component in a raft of “green recovery” measures. Just 20% of the £1.5bn scheme is set to be spent.

In their election manifesto back in 2019, the Conservatives pledged to spend £9.2bn on energy efficiency in “homes, schools and hospitals” by 2030. Of this, £6.6bn was set for delivery by 2025.

According to Pedro Guertler from E3G, with the additional funding pledged in the heat and buildings strategy, the government has committed to £4.6bn in this period, leaving a gap of £2bn.

This gap is even wider when considering what is needed to reach net-zero, with Energy Efficiency Infrastructure Group (EEIG) analysis suggesting an additional £3.6bn of funding will be required up to 2024-25 to get the nation on track.

Similar funding gaps exist in the government’s plans to support uptake of heat pumps, as outlined in the section below.

Prof Jim Watson, an energy policy researcher at University College London and member of the government’s advisory group on the heat and buildings strategy, said in a statement that funding for low-carbon heating in the government’s plan is “modest”, with “too little focus” on energy efficiency:

“So it will need to be followed up by a ratcheting up of ambitions in the coming months and years if the UK is to stay on track to be a climate-change leader – and to meet medium- and long-term targets.”

Is the government banning and ‘ripping out’ gas boilers?

Perhaps the biggest new announcement is a “confirmed ambition” to end the sale of fossil fuel boilers – which mainly use natural gas – by 2035 and replace them with low-carbon alternatives.

While other European countries are considering similar targets, this move has been welcomed as a world first. (Although the Scottish government has already released its own “heat in buildings” strategy, pledging to phase out new fossil-fuel boilers by 2030.)

The announcement comes after the government announced in 2019 that no more gas boilers would be installed in newly built homes from 2025. Last year’s energy white paper also said the government “expected” all new heating systems to be low-carbon or capable of converting to low-carbon fuel by the “mid-2030s”.

This component of the strategy had been heavily briefed ahead of the announcement – and not always favourably. Despite this, it is worth noting that at the citizens’ Climate Assembly, 86% of attendees backed a ban on the sale of new gas boilers from 2030 or 2035.

Analysis by consultancy Aurora Energy Research hammered home the importance of such a target, noting that delaying the phaseout to 2040 could leave a quarter of today’s home heat emissions unaddressed by the net-zero deadline in 2050 – “roughly equivalent to running a 2 gigawatt (GW) coal-fired power station 24 hours a day for the full year”.

Responding to widely reported stories about the government “ripping out” people’s gas boilers, the initial press release seems to be fending off criticism by stating that “no-one will be forced to remove their existing fossil fuel boilers”.

While it was generally reported as a “ban”, the 2035 target was framed by the government as an “ambition” and a “target”.

Being a cynic, I’d say “confirmed ambition” is constructively ambiguous enough for all in Cabinet to agree to & to spin as appropriate

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) October 18, 2021

So…it’s a ban! But also, not a ban!

Given press around this, I’m not surprised.

(+Basically if market/public treats as ban, it’s a ban.) pic.twitter.com/Qo4fgJ2rZ2

Despite the minor controversy around this target, it is considerably less ambitious than the CCC’s recommendations. The advisers have stated that gas boiler sales should end in the UK by 2033 in residential properties to stay on a pathway for net-zero and that this date should be 2030-33 in commercial properties.

Around 1.1m homes in England are not connected to the gas grid, but still use fossil fuel heating, of which 78% use heating oil, 13% use liquid petroleum gas and 9% coal.

The CCC has said the phaseout date for oil boilers in homes should be 2028 and 2025-26 in commercial properties. However, the government has launched a consultation that proposes an end to new sales of this technology by 2026 in homes – two years earlier than the CCC’s proposal.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) said in a report earlier this year that an end to all purely new fossil-fuel boilers should be introduced globally as early as 2025 in order to stay on a net-zero trajectory.

An important point to note is that both the CCC and the IEA make allowances for boilers that can be converted to use hydrogen instead of natural gas – but are still essentially gas boilers.

The government includes a similar caveat, potentially allowing the continued sale of “new technologies like hydrogen-ready boilers, where we are confident we can supply clean, green fuel” beyond 2035.

The strategy says that the government will “soon” consult on enabling, or requiring, new gas boilers to be hydrogen-ready, but will include a phaseout of hydrogen-ready boilers “in areas not converting to hydrogen” in its 2035 target.

Pedro Guertler from E3G tells Carbon Brief that while the gas boiler phaseout is “world leading”, there is a “risk” that without sufficient support for heat pumps (see below) the target could end up being met with hydrogen-ready boilers instead.

Many experts think that there will only be limited volumes of clean hydrogen available in the coming years and that it should be reserved for sectors, such as steel manufacture, that are difficult to decarbonise without it. An advert by Worcester Bosch, a promoter of hydrogen heat, even states that hydrogen will not be widely available until the 2030s.

New advert for hydrogen-ready boilers from Worcester Bosch. The message is clear: your new gas boiler will burn fossil fuels for a long time. And hydrogen will not be available until the 2030s. https://t.co/trPq2P8NjK pic.twitter.com/YrbhipTvpV

— Jan Rosenow (@janrosenow) June 30, 2021

If there was insufficient hydrogen, these “hydrogen-ready” boilers would likely continue burning natural gas. The evidence also points to hydrogen being a much less efficient source of clean heat than alternatives such as electric heat pumps.

Despite leaving the door open for hydrogen in domestic heating, the government ultimately says that “no regrets” heat-pump technology will “play a key role in all scenarios” and delays a firm decision on hydrogen’s role in homes until 2026, even as it pushes ahead with support for heat pumps.

However, the document does mention that the government will explore blending up to 20% hydrogen into the gas network, with an “indicative assessment” planned by autumn 2022 and a final policy decision in 2023.

How will the government support the expansion of heat pumps?

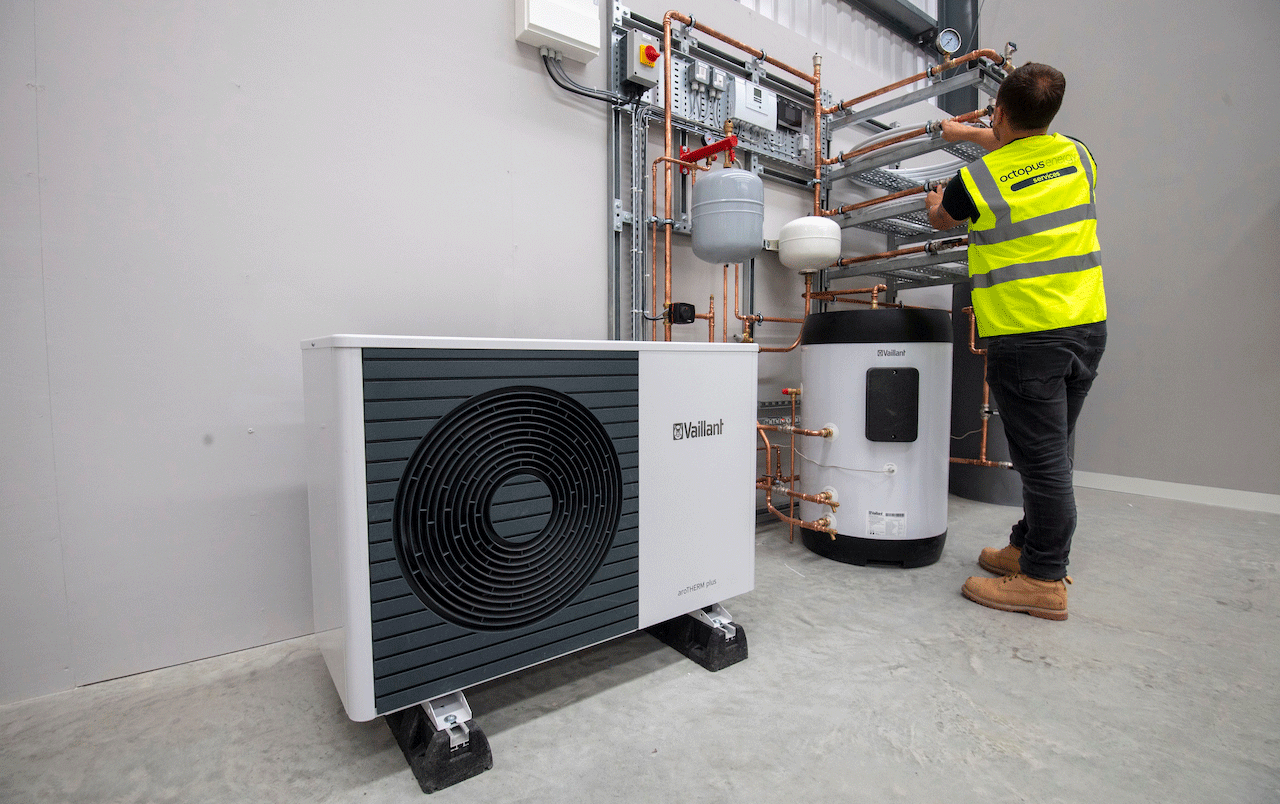

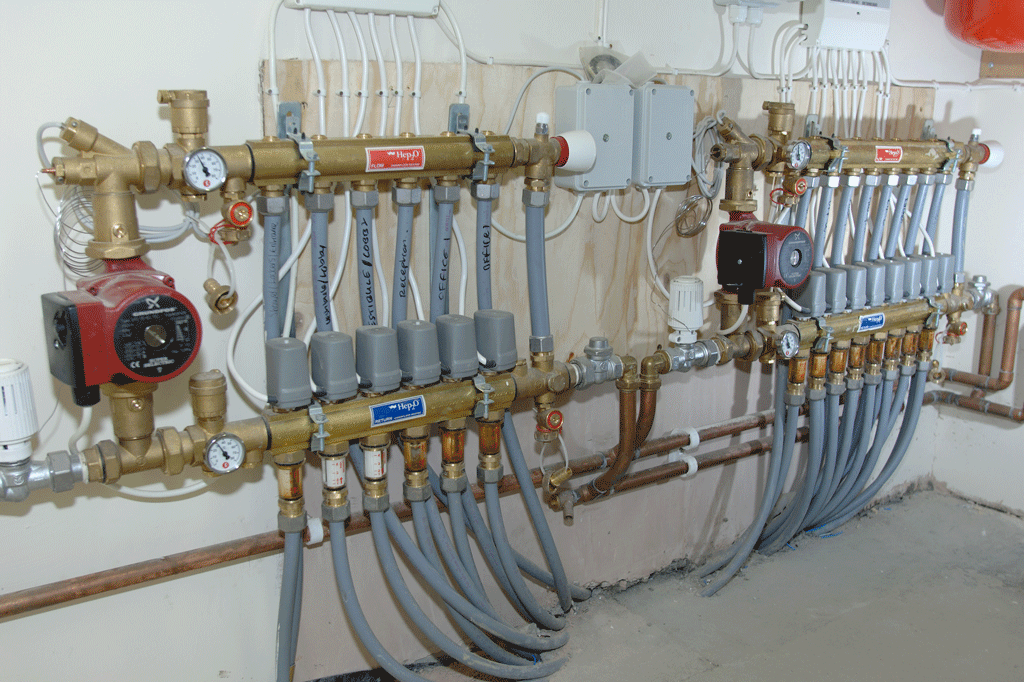

The heat and buildings strategy makes it clear that the government sees electric heat pumps – often described as working like “reverse fridges” that transfer heat from outside sources into homes – as central to its net-zero strategy.

While the government says that a “mix of low-carbon technologies” will likely be used in future heating, including heat networks and low-carbon hydrogen, much of the document focuses on developing heat-pump supply chains and improving their appeal.

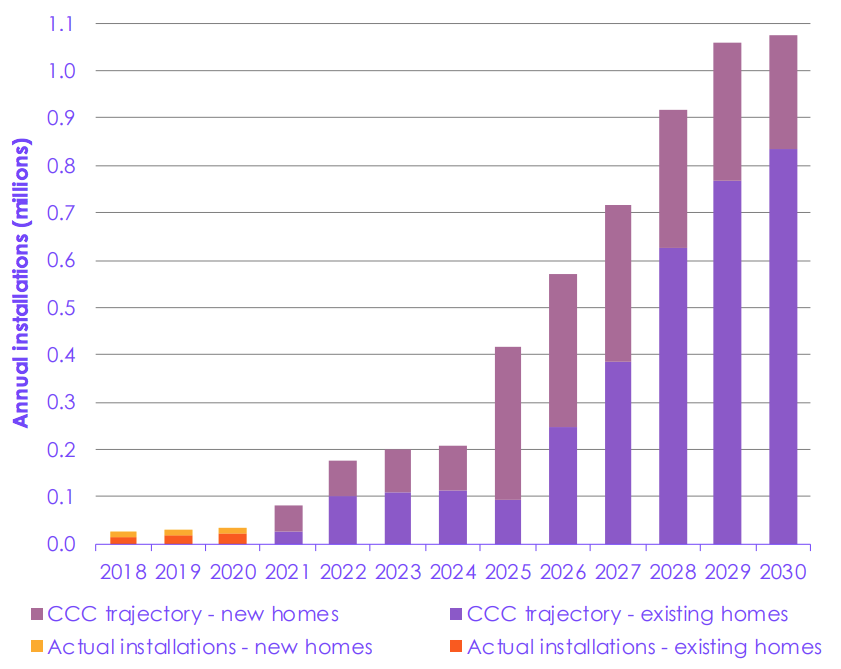

In previous announcements, the government committed to installing 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028, a roughly tenfold increase from the 67,000 units sold in 2021 so far.

The strategy reiterates this goal, stating that this is the “minimum number that will be required…to be on track to deliver net-zero”, noting that approximately 200,000 of these are expected to be in new-build homes.

(It specifies “hydronic” heat pumps – also known as air-to-water – which can supply hot water and, therefore, fully decarbonise the heating of buildings.)

The report also states that meeting this target is “contingent on the market finding ways to reduce the upfront cost of the systems, while continuing to improve consumer experience and appeal”.

The CCC, in contrast, recommends that 900,000 heat pumps should be installed by 2028.

In its latest progress report, the CCC said that the shortfall in government targets in some sectors compared to the committee’s own would have to be made up for elsewhere to stay on track for net-zero, giving the discrepancy in heat-pump targets as an example.

Cost is seen as the major barrier to heat pump uptake, but the government’s press release emphasises big “expected” price reductions of 25-50% by 2025 “as the market expands and technology develops”. It even states that the aim is for heat pumps to cost the same to buy and run as fossil-fuel boilers by 2030.

We often get asked what the costs of heat pumps are. Thought I’d share this great chart from @elementenergy which breaks down household costs in our scenarios.

— Jenny Hill (@JennyC_Hill) August 12, 2021

Kit-wise, ASHP (air source heat pump) is on average £6.5k now- including a hot water cylinder/storage adds £1k… pic.twitter.com/OWPFSuWvKx

A centrepiece of the strategy is a new £450m, three-year “boiler upgrade scheme” – the outcome of a consultation on a “clean heat grant” – which is set to launch in April. This will offer homeowners grants of £5,000 when switching to an air-source heat pump or £6,000 when switching to a ground-source one.

While this grant featured in many newspaper headlines, it received a fairly lukewarm reception from policy experts and NGOs. Dr Jan Rosenow of the Regulatory Assistance Project tells Carbon Brief:

“The funding that has been allocated for heat pumps is very, very small – 30,000 units a year, that’s pretty much what we currently install already.”

He also notes that with a previous funding programme, the renewable heat incentive coming to an end, the new grant is unlikely to significantly boost the market.

From these 90,000 sales, the industry is required to reduce the installation cost of a heat pump by 25-50%. The RHI managed to deploy about 55,000 domestic heat pumps and delivered, well, less cost reduction than that. /14

— Adam Bell (@Adam_Grant_Bell) October 19, 2021

Analysis by Octopus Energy’s Centre for Net Zero concludes that with the grant scheme available to 90,000 households in total, this funding would leave significant unmet demand across the UK.

Based on estimates of this demand, the centre suggests that an unlimited grant could support 380,000 heat pumps by year three, more in line with the CCC’s figures for a net-zero trajectory.

In a statement, Centre for Net Zero chief executive Lucy Yu said that “meeting that unmet demand with further grant funding would bring costs down for the majority more quickly by supporting learning effects”.

Pedro Guertler from E3G found that in order for the government’s boiler upgrade scheme to meet its own target of 600,000 heat pump installations, it would need an additional £850m. This figure nearly doubles to £1.65bn if installation rates are to be in line with net-zero.

Guertler also found a shortfall in funding for low-income households – which need larger grants of around £10,000, according to his analysis – totalling between £1.5-2.5bn.

E3G notes that funding for such households can come from the HUG and SHDF, but using these pots would take away money that could be spent on energy efficiency.

One crucial component of the strategy is a new consultation, launched alongside the main document, on a market-based mechanism to support the rollout of heat pumps.

Under the lead option that the government says it is “most likely to pursue,” there would be an obligation for the manufacturers of gas and oil boilers to sell a rising number of heat pumps, proportional to their sales of fossil fuel systems across a period of time.

It adds that this proportion “could then, in principle, be stepped up over time, in line with the ambitious, but achievable scale of growth in low-carbon heating that is needed”. This mandate could be used to drive the uptake of the remaining 400,000 heat pumps not installed in newly built homes up to 2028, the consultation suggests.

In order to help develop the heat-pump market, the strategy also includes a new £60m “heat-pump ready” innovation programme.

Finally, another “no-regrets action” identified by the government besides heat pumps is the development of low-carbon heat networks – systems of pipes that distribute heat from a central source, such as a combined heat-and-power plant, and deliver it to buildings.

It emphasises the importance of developing a market for these networks, recognising the CCC’s recommendation that around 18% of UK heat should come from these networks “as part of a least-cost pathway to meeting net-zero”.

How will it keep low-emissions heating costs down?

Heat pumps will be a less appealing option if, once a household has purchased one, it is more expensive to run than the alternative gas boiler.

As it stands, environmental levies that are added to customers’ electricity bills, such as the renewables obligation and feed-in-tariffs, are a barrier to progress, as a July report from the Office for Budget Responsibility explains:

“Perversely, these levies incentivise the use of gas over electricity for household and business customers, thereby slowing the transition to cleaner energy.”

Moreover, the UK only has a carbon price on electricity and industry, while gas is effectively subsidised.

This situation is recognised in the heat and building strategy, which states that “current pricing of electricity and gas does not incentivise consumers to make green choices, such as switching from gas boilers to electric heat pumps”.

Given that heat pumps are around three times more efficient than gas boilers, they will be cheaper to run if each unit of electricity costs less than three times as much as gas – an achievable goal if levies are removed.

let’s say now

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) July 5, 2021

£elec = 14p

£gas = 4p

(rounded avg from https://t.co/F5luOjMyka )

then if policy costs are taken off elec

£elec = 11p

£gas = 4p

so you’re already at £elec < 3x £gas

and then if gas faces a modest CO2 price…

The strategy states that the government wants to reduce the cost of electricity and plans to explore ways to “shift or rebalance” energy levies.

It notes that this will “include looking at options to expand carbon pricing and remove costs from electricity bills while ensuring that we continue to limit any impact on bills overall”.

To this end, the strategy announces the launch of a “fairness and affordability call for evidence” on these options, with the goal of making a decision in 2022. (At the time of publication, this call for evidence had not been released.)

This topic, while technical, has been a major source of tension in the press in the run-up to the strategy’s launch. This is because placing an additional charge on gas use could, without mitigating policy elsewhere, unfairly target low-income households who are least able to pay to switch to electrical alternatives.

A Sun article quoted a select committee hearing in which experts warned that simply swapping levies from electricity to gas would increase energy bills “on average by £65 a year for poorer families”.

However, another article in the same newspaper cited more evidence that such a swap “may be able to save cash-strapped Brits hundreds on their energy bills in future”.

Analysis of the issue by thinktank Public First concluded that policy costs should be funded via the public purse, with a carbon price being applied to both gas and electricity.

It said this was the best option to balance heat decarbonisation and an appropriate price on emissions, while avoiding penalising consumers and limiting the impact on the Treasury.

Nevertheless, it found that this scenario would still result in an annual fuel bill increase of £38 a year for the average household and £40 for the fuel poor.

It is worth noting that, prior to the current crisis, energy bills had not gone up for more than a decade, despite rising prices, due to energy efficiency improvements.

The CCC’s net-zero advice noted that further efficiency improvements could offset the increase in climate policy costs on bills to 2030, and overall the government frames its heat and buildings strategy as one that will reduce people’s energy bills while also cutting emissions.

-

In-depth Q&A: How will the UK’s ‘heat and buildings strategy’ help achieve net-zero?