Updated: Two plans to begin first fracking operations in UK for four years rejected

Simon Evans

06.26.15Simon Evans

26.06.2015 | 3:05pmUpdate 29/6 – Councillors this morning voted to reject a second application to resume exploratory fracking, following publication of three separate pieces of legal advice. The refusal passed with nine in support, three against and two abstentions.

Two applications to carry out exploratory fracking in the UK for the first time in four years have been refused by Lancashire County Council’s planning committee.

The decision to refuse fracking firm Cuadrilla’s plans for Roseacre Wood near Blackpool was “very significant” and a “test case” for the UK’s nascent shale gas industry, said the BBC last week. Today’s decision to refuse plans at Preston New Road cements the situation and leaves Conservative plans to accelerate UK fracking hanging in the balance.

The Guardian calls the decision a “major blow”. The Telegraph says it is a “major setbeck” to government hopes of a shale industry.

A government moratorium on fracking was imposed in 2011 after Cuadrilla caused earth tremors at another nearby site. The council’s decisions are the first since that ban was lifted in 2012.

Carbon Brief summarises the decisions and explores what they might mean for the UK’s energy mix and climate goals.

Planning decisions

Lancashire County Council has been considering two Cuadrilla planning applications to carry out exploratory fracking. As the first since 2011, the cases have generated huge interest, attracting tens of thousands of responses to public consultation on the schemes.

In January, planning officers said the bid to resume UK fracking at Little Plumpton Farm and Roseacre Wood near Blackpool should be refused, because of noise and traffic concerns.

Cuadrilla then amended its proposals and officers said the Little Plumpton application should be accepted, on condition of further controls to limit noise. The Roseacre Wood site was still deemed to pose “unacceptable” traffic impacts because of its rural setting.

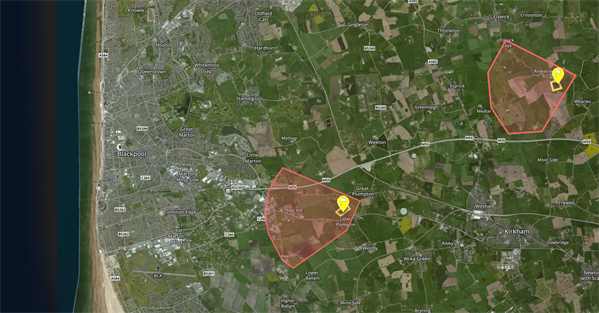

The Preston New Road/Little Plumpton Farm site (central yellow marker and red area, below) is closer to Blackpool and has easier access to trunk roads. The Roseacre Wood site (top right) is more rural.

Map of Cuadrilla’s proposed shale gas exploration sites on the Fylde peninsula in Lancashire. The yellow flags and areas show the location of each proposed well-pad. The red areas show the maximum extent of underground drilling at each site. Have a look at an interactive version. Map created by Carbon Brief with Mapbox, using information from Cuadrilla environmental statements.

On Thursday, the council’s planning committee voted to refuse the Roseacre Wood scheme, in line with the advice of its planning officer, citing the likelihood of heavy goods vehicle traffic on rural roads near the site.

On Wednesday afternoon, the committee had narrowly defeated a motion to refuse the Little Plumpton Farm scheme, despite planning officer advice to approve it. The committee then voted to defer its final decision until 10am on Monday, so that councillors could consider written legal advice prepared by David Manley QC.

Manley’s advice says he is “unclear” why some members wished to refuse the application. He goes on to say that a refusal would be “unreasonable in planning terms” and that Cuadrilla would be likely to appeal, with a “high risk” the council would have to pay the costs of this appeal.

Councillors chose to reject the scheme despite this advice, perhaps relying on the views of Richard Harwood QC for Friends of the Earth and a separate legal opinion from Dr Ashley Bows. These opinions both emphasised that councillors would be within their rights to refuse the application and that there were defensible grounds on which to do so.

A fourth piece of legal advice, from trade group the UK Onshore Operators Group, was not considered by the committee, after its legal officer argued a line had to be drawn in order to avoid constant delays to the decision as new pieces of advice came in.

Last week Catherine Davey, planning and environmental law consultant at Stevens and Bolton LLP, told Carbon Brief it is relatively common for members to go against planning officer advice, but that this increases the risk of facing costs on appeal. Bows’ advice says costs would only be awarded against the council if it was shown to have acted “unreasonably”.

Cuadrilla has six months to launch an appeal, Angus Walker, head of the planning and infrastructure department at Bircham Dyson Bell tells Carbon Brief. This would normally be heard by the Planning Inspectorate but can be “recovered” by Greg Clark, Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, meaning he would take the decision, says Davey.

Carbon budgets

There are other fracking firms and other sites waiting in the wings. Rival firm iGas says it is preparing to submit “several” planning applications over the next year. So what would it mean for the UK’s energy mix and climate goals, if a shale gas industry were to develop?

John Blaymires, chief operating officer of shale gas firm IGas, tells Carbon Brief he thinks a UK industry could reach “full scale development by about 2020”. This is at the more optimistic end of projections, with others suggesting the mid-2020s is more likely.

Shale gas is unlikely to be beneficial for the climate unless it replaces coal, with emissions savings resting upon strict controls on methane leaks. The Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) expects unabated coal to be supplying just 5% of UK electricity by 2021 and none at all by 2025. If these projections are correct, it would be hard for UK shale gas to substitute for coal.

This is one of the reasons why MPs earlier this year said fracking would be “incompatible” with the UK’s climate targets, as the carbon budget available for gas will be progressively squeezed through the 2020s and beyond.

Ken Cronin, chief executive of UK Onshore Operators Group (UKOOG), a trade group, tells Carbon Brief the UK will need gas for other purposes, such as heating and cooking. He says:

Even this window of opportunity for shale gas is limited in the UK, however. Jim Watson, director of the UK Energy Research Centre, tells Carbon Brief:

Watson is currently looking at how much gas can be used within UK climate goals, with results expected later this year. The government must follow Committee on Climate Change advice as to whether fracking is compatible with UK climate targets, following an amendment to the government’s Infrastructure Bill.

John Broderick, of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, writes that the fledgling shale industry faces a fundamental problem of declining gas demand in Europe. He says a better way to minimise the need to import gas would be to reduce demand further by tackling inefficient housing stock and boosting renewables.

Global emissions

If the UK can’t burn much of its shale gas, it could export it instead. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says gas could play a limited role in the global decarbonisation effort. That’s on the condition it replaces coal, that it is extracted with limited fugitive emission, and that global gas production is declining below today’s levels by mid-century.

But a report by Prof David MacKay, former DECC chief scientist, says exploiting UK shale in this way poses risks for global climate efforts:

MacKay tells Carbon Brief that the exploitation of any new fossil fuel sources will face the same problem, which is not unique to UK shale gas. MacKay says that his report’s focus on cumulative global emissions is “essential”.

The need for a global view is illustrated clearly by Lord Chris Smith, chair of the industry-funded Task Force on Shale Gas and former Environment Agency chair. At a shale gas conference in London this week he said:

Climate politics

There is also a question about how government enthusiasm for shale gas fits within the broader context of the UK’s low-carbon transition. Smith told the conference:

The taskforce plans to publish a report on the climate impacts of UK shale gas in September, with a further report on the economics of fracking due in December. This should shed light on whether UK shale gas would be able to compete on price with imports.

Apart from the climate impacts of shale gas, there are a range of other issues worrying opponents of the industry. These include potential water contamination, noise, wildlife, house price and visual impacts. Carbon Brief has a summary of the main issues.

Main image: People gather together for an anti-fracking protest march against the energy company Cuadrilla, August 2013, in Balcombe, UK.

-

Two applications to carry out exploratory fracking in the UK for the first time in four years have been refused by Lancashire County Council's planning committee