Q&A: What does the ‘High Seas Treaty’ mean for climate change and biodiversity?

Multiple Authors

03.08.23Multiple Authors

08.03.2023 | 3:05pmNations around the world have agreed to a new global treaty for governing the sustainable use and conservation of the so-called “high seas” – areas of the ocean that lie outside of any single nation’s jurisdiction.

The agreement on “biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction”, better known by the acronym “BBNJ”, establishes a new United Nations body to oversee the implementation of the principles and approaches laid out within the text.

The treaty was nearly 20 years in the making and, right up until the last moments, it was unclear to observers whether an agreement would even be reached during the marathon session, which took place at the UN headquarters in New York.

Negotiations stretched well past their scheduled end, carrying on through the night of 3 March and only concluding at 9:53pm on 4 March, ending two weeks of talks.

Issues of access – from too-small meeting rooms to the inconsistent availability of interpreters – arose at several points throughout the negotiations.

Some observers also objected to the shorthand terminology of the “high seas” treaty, saying that it centres the principle on the “freedom of the seas” instead of international waters being a common good for humankind. Both overarching principles made it into the final text.

The drawn-out negotiating process means that the agreement still needs to be formally adopted and ratified. But the draft treaty is being hailed as a success by many.

Addressing the plenary session late on 4 March, Singapore’s Rena Lee, who oversaw the process, was visibly emotional. She told the assembled delegates: “The ship has reached the shore.”

In this article, Carbon Brief explains the background of the negotiations, the details of the final treaty and what it means for climate change and biodiversity loss.

- What is the ‘high seas treaty’?

- Why does the treaty matter for climate and biodiversity?

- What does the treaty say?

- What has the reaction been?

What is the ‘high seas treaty’?

The BBNJ treaty sits underneath the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into force in 1994 and counts 167 countries, plus the EU, as parties.

A further 14 member states have signed, but not ratified, UNCLOS, while the US has signed the agreement on implementation, but not the convention itself. The US could ratify the new treaty without being a party to UNCLOS. But, as with many multilateral frameworks, reaching the two-thirds majority required in the US Senate that is required for ratification may be a tall order.

UNCLOS establishes a mechanism for governing marine and maritime activities, including allowing for the freedom of scientific research, the exclusive economic rights of countries and reducing pollution.

UNCLOS and its implementation agreement established the International Seabed Authority, which governs activities on the seafloor beyond national jurisdiction.

However, areas beyond national jurisdiction (sometimes referred to as the “high seas” or international waters) have long been a blind spot with regards to UNCLOS.

The high seas are the parts of the ocean that are outside of any nation’s “exclusive economic zone” (EEZ). EEZs extend 200 nautical miles (about 370km) from the shore.

This 200 nautical-mile extent means that some parts of the ocean – such as the Mediterranean – do not fall outside of national jurisdiction at all. Similarly, the South China Sea is fully covered by various countries’ EEZs, although overlapping claims there have led to long-standing disputes.

Initial informal consultations on what would become the BBNJ treaty began in 2004, with a UN resolution (pdf) adopted on 17 November of that year. That resolution read, in part:

The working group established by the initial resolution met periodically over the remainder of the decade. Its consultations culminated in 2011 with the adoption of recommendations to start work on a legal framework governing biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction.

From there, discussions around the treaty moved under the purview of the BBNJ preparatory committee, which met four times between 2016-17.

Finally, in a resolution (pdf) passed on 24 December 2017, the UN General Assembly decided “to convene an intergovernmental conference…and to elaborate the text of an international legally binding instrument” on conserving and sustainably using biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

That resolution also affirmed four focus areas for the treaty:

- Marine genetic resources, including the sharing of benefits from these resources.

- Area-based management tools, such as marine protected areas.

- Environmental impact assessments.

- Capacity-building and technology transfer.

According to the 2017 resolution, the UN would convene four sessions of the intergovernmental conference (IGC) – one in 2018, two in 2019 and a final one in 2020.

The purported final session, IGC4, was delayed twice due to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and, ultimately, was held in mid-March 2022 at the UN headquarters in New York.

Although IGC4 was hailed as “the most productive meeting so far”, in which delegates made “unprecedented progress”, parties were unable to come to an agreement during that session.

Delegates reconvened for IGC5 in August of last year in New York – the second “final” session. The negotiations came closer to consensus than they ever had before, but, again, no agreement could be reached.

The resumed session of IGC5 was scheduled from 20 February to 3 March 2023, although a marathon final negotiation session meant that agreement was not reached until nearly 10pm local time on 4 March.

The treaty must now move through a technical edit and translation into each of the UN’s six official languages before being adopted by UN member states.

IGC president Rena Lee made it clear during the plenary sessions of the final negotiation day that, while the IGC must meet again for the formal adoption of the treaty, it will not be reopened for further negotiations.

The treaty must be ratified by 60 member states before it can enter into force.

Why does the treaty matter for climate and biodiversity?

The high seas cover nearly two-thirds of the global ocean – almost half of the Earth’s entire surface. The ocean, as a whole, takes up 90% of the excess heat and around 25% of the CO2 generated by humanity’s burning of fossil fuels.

But the lack of formalised protections for much of the ocean has left it vulnerable to overfishing, pollution and the effects of climate change.

The preamble to the new treaty “recognis[es]” the need to address biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation in the ocean “in a coherent and cooperative manner”.

It also identifies several drivers of marine biodiversity loss, among them, impacts from climate change, ocean acidification, pollution and “unsustainable” use.

There is “a very direct link” between climate change and biodiversity loss that the new treaty can help address, says Ismail Zahir, Samoa’s principal adviser for oceans and sustainable development. Samoa is currently the chair of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS). He tells Carbon Brief:

“This was something that all of the G77 [group of developing nations] really fought hard for – to establish this strong link, especially including the role that the ocean has in the carbon cycle and climate mitigation.”

Zahir also notes that the improved scientific and technical capacity generated from the treaty will help small-island developing states better understand the climate change impacts they are already facing.

In the lead-up to the most recent negotiations, the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative, a network of academics and other experts that provides advice on sustainable use and biodiversity in the deep sea, released a policy brief (pdf) urging stronger links between climate change policy and the BBNJ treaty.

The brief called the negotiations “a vital opportunity to better integrate biodiversity protection with climate change action”. It pointed out several places where climate change could be better integrated into the agreement.

Although climate change law and the law of the sea have historically been treated separately, “the international community is pushing for more connectivity between the two topics recently”, says Luciana Coelho, a Brazilian lawyer and a PhD candidate at the World Maritime University.

Coelho, who is also part of the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative, tells Carbon Brief that one reason the new treaty is so important is that it “starts a conversation between these two legal regimes” and adds that it is “quite weird” that the two were so separate to begin with.

Angelo Villagomez, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a Washington DC-based thinktank, says the new treaty “is a great step forward for overall ocean health”. Villagomez, who is Chamorro, from the Northern Mariana Islands, tells Carbon Brief:

“There’s a lot of scientific literature that has looked at different types of protected areas and found that the ones that result in the greatest outcomes for biodiversity are the ones that restrict the most fishing.”

While several media outlets and commentators have erroneously stated that the world has now agreed to preserve 30% of the world’s high seas by 2030, the finalisation of the BBNJ treaty makes no such guarantees.

Rather, it provides the framework for establishing protected areas where previously there had not been a clear mechanism for doing so.

However, experts say that the framework set out in the new treaty is critical in order to achieve the 30% conservation by 2030 target set out at the UN biodiversity summit, COP15, in December 2022.

Speaking to Carbon Brief at that meeting, WWF’s global ocean practice leader, Pepe Clarke, said:

“Our ability to achieve 30% protection of the oceans is partly about the ambition that is set here, at the CBD, but also about governments finally – hopefully – next year reaching an agreement on conservation of the high seas.”

What does the treaty say?

Purpose and principles

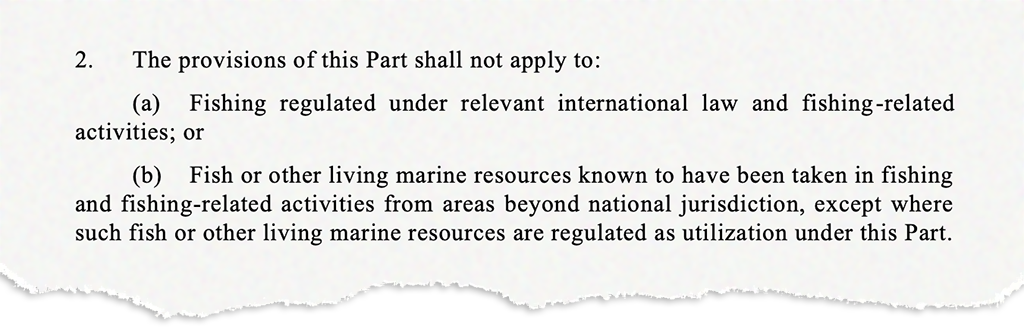

The first part of the treaty sets out its purpose, principles, definitions and exceptions that are not specific to any one section, but could apply to all of them. It also provides framing for the context and narratives in which the treaty sits and defines its relationship to other legal instruments and bodies.

States were deeply invested in what is defined, undefined and acknowledged in the BBNJ treaty – even more so given that the treaty is legally binding.

The preamble articulates “the need for the comprehensive global regime…to better address the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction”.

It also “recognises”:

“The need to address, in a coherent and cooperative manner, biodiversity loss and degradation of ecosystems of the ocean, due to, in particular, climate change impacts on marine ecosystems, such as warming and ocean deoxygenation, as well as ocean acidification, pollution, including plastic pollution and unsustainable use.”

If the treaty is adopted, it would mark the first time in history that a UN treaty’s preamble refers to plastic pollution. This would set the stage for upcoming negotiations towards a binding plastics treaty in May this year

🚨🚨 👏 to delegates & CSO for the conclusion of the #HighSeasTreaty negotiations

— Andrés Del Castillo #PlasticsTreaty 🇺🇳 (@andresdelcas) March 5, 2023

💥If adopted, the #HighSeasTreaty will be the first treaty with a direct preamble reference to #plasticpollution

The #bbnj text will be forward to an OEIWG before its adoption. #plasticstreaty pic.twitter.com/EZ8yQbLosF

In a win for human-rights advocates closely watching the text, the preamble “recalls” the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and affirms that nothing in the agreement will diminish or extinguish the existing rights of Indigenous Peoples or, “as appropriate”, local communities.

Some delegations consistently opposed the capitalisation of “Indigenous Peoples” in the text, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

The preamble also refers to “caring for” and “conserving the inherent value of biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction” and that says that parties “des[ire]” to “act as stewards of the ocean” on behalf of present and future generations.

Fair and equitable benefit-sharing from marine genetic resources and digital sequence information are mentioned twice in the preamble.

The beginning of the treaty carefully underlines its respect for “the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of all states”, while recalling that “states are responsible for the fulfilment of their international obligations concerning the protection and preservation of the marine environment” and can be held liable if they do not comply.

In separate articles on overall “exceptions” and “application”, the treaty clarifies that the agreement, including the section on the use of marine genetic resources, does not apply to military vessels or military activities.

However, countries are to ensure that their warships and aircraft “act in a manner consistent, so far as is reasonable and practicable, with this Agreement”, the treaty continues.

Some of the key fights were in Article 5, which covers “general principles and approaches”. This is because a principle can direct how rules in the treaty should be applied.

The “freedom of the high seas” refers to the existing legal regime around the oceans, which is an open-access, free-for-all regime.

Proposed as early as 1609 to imply that the high seas were open to all nations and not subject to national sovereignty, the concept is associated with commercial and maritime empires whose needs it served.

Today, it is recognised by UNCLOS as “freedom of navigation, freedom of fishing, freedom of overflight, freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines, to make installations and artificial islands and freedom of scientific research”.

But as countries overfished, dumped their wastes and continued to exploit resources – especially oil extracted from continental shelves – the freedom of the high seas has become seen as a right to pollute and over-extract, with no limits on unsustainable use, no benefits to be shared and no commitment to conserving the marine biodiversity of the high seas.

Exclusive off-shore fishing rights and the rise of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) also meant that the high seas were subject to a degree of national sovereignty. Meanwhile, concerns around bioprospecting and deep-sea mining continue to grow.

The “common heritage of humankind” principle, conversely, sees the oceans and high seas as a complex ecological system and as a global ocean commons that belongs to humankind, meant to sustain present and future generations.

When included in a legal treaty, states then bear a legal responsibility to act in the common interests of all humanity to protect and preserve biodiversity outside their national waters, and not out of individual national or economic self-interest.

Discussions on the inclusion of this common heritage principle in the BBNJ text were heated even during week one, and continued right up until the finish line. The EU, Russia, Iceland, Australia, Japan and the Holy See all wanted it removed from the text.

According to Dr Siva Thambisetty, an intellectual property expert at the London School of Economics and an advisor to the G77+China bloc of developing countries, there was “insistence in the final hours that biodiversity on the high seas was subject to the freedom of the high seas”.

In the final text, “common heritage of humankind” appears on par with “freedom of marine scientific research, together with other freedoms of the high seas”.

Thambisetty tells Carbon Brief:

“The G77 group took a strong view of the need for the common heritage of mankind to be recognised as central to the treaty, finding a landing zone on the freedom of marine scientific research on the high seas, instead. Compromises were made on both sides – and we can all be proud of what we achieved here.”

Article 5 also includes the polluter-pays principle, which places responsibility on polluters to manage and bear the costs of their pollution, and the precautionary principle, which means that states should not let the lack of scientific certainty hold them back from responding to threats of serious, irreversible damage to the high seas.

The principles also fully recognise the “special circumstances of small island developing states and of least developed countries”, and separately, the interests of land-locked states.

Zahir, Samoa’s adviser for oceans and sustainable development, tells Carbon Brief:

“For us, this is really important, because activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction have very profound impacts on our territorial waters because of the connectivity of the ocean…Towards the very end of the talks, parties were suggesting language like ‘taking into account’ and we said ‘No, we will not accept this instrument as a whole, unless the special circumstances of SIDS are given the full recognition they need.’ That was a very big win for us.”

Governance and institutions

Setting up rules and institutions to govern the ocean commons under a legally binding treaty has been fraught with tensions.

Many countries have held red-line positions around sovereignty, territorial integrity, political independence and disputed areas. These positions needed to be respected to ensure that parties would even come to the table, let alone ratify such a treaty.

Sovereignty, for example, is integral to the Paris Agreement, which hinges on nationally determined contributions. The non-binding nature of the Paris Agreement was also key to its adoption.

Some experts tell Carbon Brief that the only reason why some countries would agree to be part of these negotiations was that it dealt with areas beyond national boundaries – even though it also has implications for the rest of the oceans.

That said, countries that ratify the agreement will have to develop laws, institutional mechanisms and policies at the national, regional and global levels.

The treaty establishes seven mechanisms and bodies to take its work forward:

- A Conference of the Parties (COP), which will serve as a decision-making body.

- A secretariat, which will provide administrative and logistical support, circulate information and facilitate cooperation and coordination with other international bodies.

- A clearing-house mechanism managed by the secretariat, which will serve as a centralised, open-access platform for parties to access and provide information, including on marine genetic resources, environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and the establishment of marine protected areas.

- A Scientific and Technical Body (STB) of expert members from different geographies with multidisciplinary expertise, including traditional knowledge, nominated by parties and elected by the COP to advise it.

- An Implementation and Compliance Committee (ICC) that is “facilitative in nature and function in a manner that is transparent, non-adversarial and non-punitive”.

- An access and benefit-sharing committee.

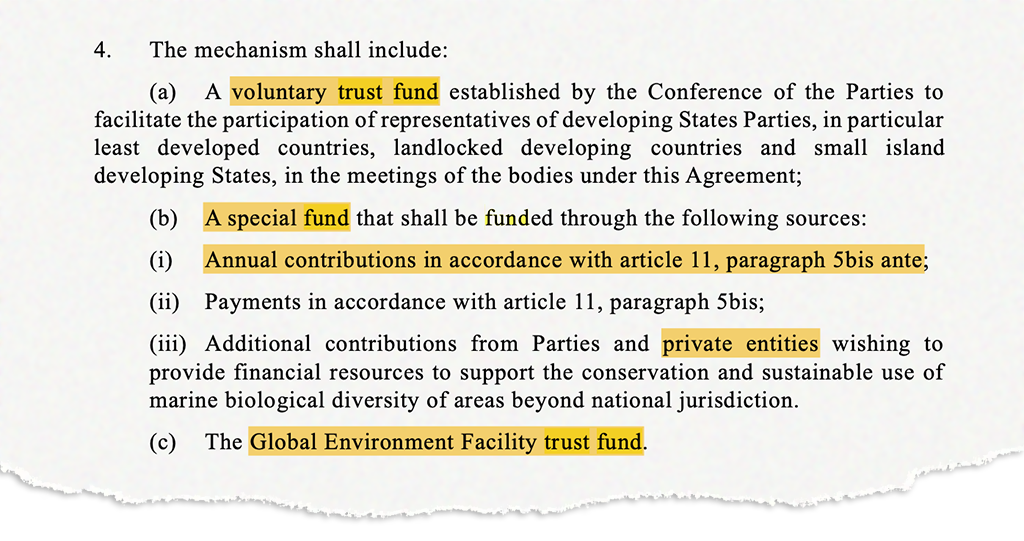

- A financial mechanism that has a voluntary trust fund, a special fund and a Global Environment Facility (GEF) trust fund that will accept contributions from all states, benefit-sharing payments from developed countries and additional contributions from public and private entities.

In addition to its advisory role, the Scientific and Technical Body is also tasked with developing guidelines and standards for EIAs, as well as reviewing EIA projects and proposals from countries and making recommendations. (See: Environmental impact assessments.)

Experts have, so far, welcomed the treaty’s final architecture. Nichola Clark at the Pew Charitable Trusts, tells Carbon Brief:

“I think it’s really exciting that they’re setting up a brand new body. It’s got a good and robust institutional structure to really help make sure that this agreement is an active agreement and states are actively using it to implement and achieve the objectives of conserving and sustainably using biodiversity in the high seas.

“It’s also looking like it will also set up an implementation and compliance committee, which is going to be really helpful to make sure implementation is effective and states are held accountable.”

Clark also says that that the establishment of the implementation and compliance committee “is going to be really helpful” to hold states accountable, but “it’s definitely meant to be more of a carrot compliance committee, rather than a stick compliance committee: non-adversarial, non-punitive to help advance and support implementation.”

So far, the intergovernmental conference established by the UN General Assembly in 2017 has served as the president of all six negotiation sessions for this treaty. With its job nearly concluded, the baton now stands to be passed on to the COP.

In the interim, the secretary-general, through the UN’s Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), shall serve as the treaty’s secretariat, providing administrative and logistical support, arranging COP meetings, publicising the treaty and coordinating with other treaty secretariats, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

The first COP meeting under the treaty will be convened by the UN secretary-general “no later than one year after” the treaty enters into force. It will “meet ordinarily” at the seat of its secretariat – a venue to be decided at the first COP – or at the UN headquarters in New York.

At its first meeting, the newly minted COP is tasked with framing the rules of procedure for itself and its subsidiary bodies, the rules governing its funding, and its budget and those of any subsidiary bodies it chooses to establish.

The COP must take stock of the effectiveness of the treaty and its provisions five years after it takes force and, if necessary, propose means to strengthen its implementation.

Decision-making

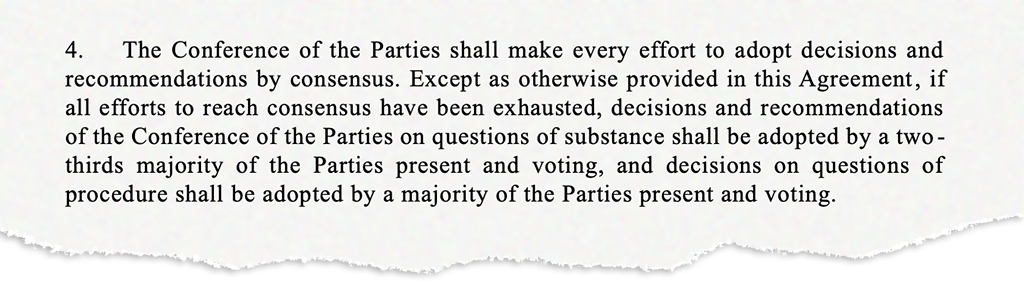

An important way that the new treaty’s COPs will stand apart from climate COPs is in how it makes decisions when there is no consensus.

Consensus – and what to do when there is none – is an issue that has besieged climate COPs for years. On the surface, consensus is the de-facto decision-making option for countries under the climate COPs, with each party given an equal voice.

Nothing is agreed until everything – and everyone – is agreed, as the saying goes.

However, several climate COPs have shown that this is not always the case: Copenhagen, Cancun and Doha most notably (in 2009, 2010 and 2012, respectively), where countries made serious objections, but these did not lead to decisions being overruled.

With climate COPs increasingly running into serious overtime and decisions pushed to the wire, debates have resurfaced as to whether voting could be an option. (Technically, voting is an option, under rules of procedure that have never been adopted because of divergent views on voting.)

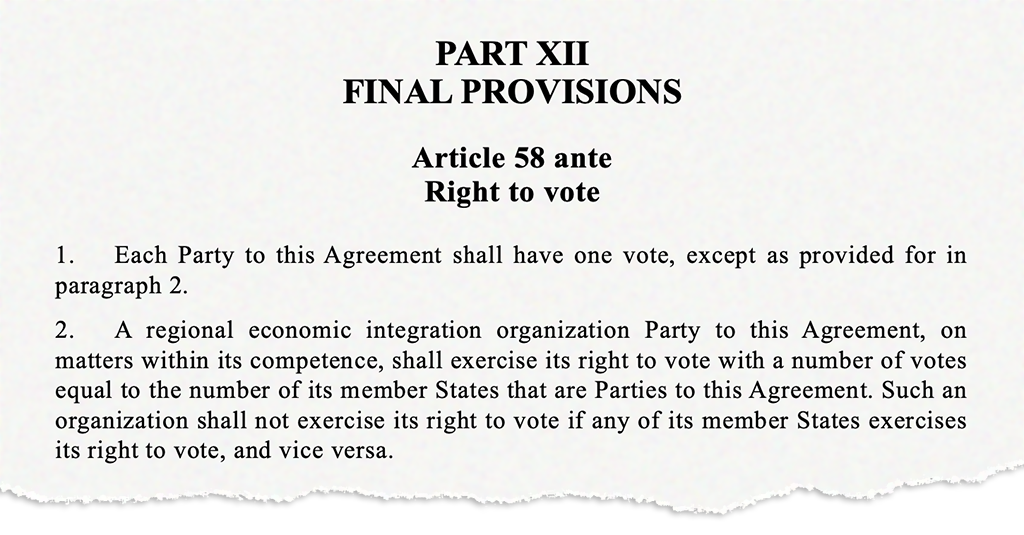

At the BBNJ negotiations, voting and consensus was one of the last cross-cutting issues to have its square brackets (areas of disagreement) dropped in the negotiating text. Under the treaty, each party has one vote. Regional economic organisations, such as the EU, can either vote as a bloc, with its vote as the sum of member countries, or as individual countries.

The agreement allows voting as a last-resort option on a range of issues, from the creation of marine protected areas (see: Marine Protected Areas section) to how the COP decides.

For COP decisions when there is no consensus, two-thirds of all representatives present and voting can decide on “questions of substance”, while decisions on “questions of procedure” will be adopted by a majority of parties present and voting.

However, on decisions around EIAs, the COP can only assist and advise. From the start to finish, be it screening projects or deciding whether to halt them, it is up to the party hosting a project or planned activity to decide.

Finance

The treaty will need monetary support and partnerships to ensure that its adoption and implementation have the teeth to advance cooperation, science and action. It will also need to meet the capacity-building needs of states that cannot afford to do so.

The financial mechanism established in the treaty for “adequate, accessible, new and additional and predictable financial resources” sets out different sources of funding to meet these objectives.

It calls for all parties, “within [their] capabilities”, to provide resources and says that the institutions established under the agreement “shall be funded through assessed contributions of the Parties”. Private actors can also contribute to support conservation and sustainable use.

The financial mechanism will also establish a “special fund”. This fund is to ensure that “any monetary benefits, including commercialisation, derived from marine genetic resources in areas beyond national waters and the associated digital sequence information “shall be shared fairly and equitably…for their conservation and sustainable use”. (See: Marine genetic resources.)

Once the treaty enters into force, developed countries must make an up-front annual contribution to that special fund under the financial mechanism, amounting to an additional 50% of their assessed contribution to the budget adopted by the COP.

Developing country parties tell Carbon Brief that they fought to make sure this amount was “at least 100%” of developed countries’ assessed contribution.

“They only agreed to this with the caveat where COP decisions can adjust or overrule this,” one developing country negotiator tells Carbon Brief.

The COP, consulting with the access-and-benefit committee, will decide how these monetary benefits to the special fund will be shared. This could be a tiered fee, milestone payments or a percentage of revenue from the sale of products derived from marine genetic resources or their data.

It will also set an “initial resource mobilisation goal through to 2030 for the special fund from all sources”. This will be done “in recognition of the urgency to address the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction”.

The special fund and the GEF fund can be used to sponsor capacity-building projects ranging from conservation through to marine technology transfer training. These sums would also be used to assist developing states, support Indigenous communities’ conservation and sustainable-use efforts and to support public consultations.

During the recently concluded session, Palestine pledged up to $50,000 for capacity building and transfer of marine technology – a concept that spans the exchange of data, expertise and access to infrastructure and collaboration. The EU pledged €40m to support the early ratification of the treaty, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin reported. At the parallel Our Ocean conference in Panama, the EU Commission announced €820m for ocean protection.

Marine protected areas

One of the four major components of the new treaty is the use of area-based management tools, in areas outside of national waters, such as marine protected areas (MPAs).

The term “area-based management tools” encompasses a wide range of approaches. These can cover a single sector, such as in the case of regional fisheries closures, or be multisectoral, such as in the case of MPAs. MPAs offer a higher degree of protection than other area-based management tools.

The treaty’s objectives surrounding area-based management tools include that it “conserve and sustainably use areas requiring protection” and that it “strengthen resilience to stressors, including those related to climate change, ocean acidification and marine pollution”.

It further states that these managed areas should be “ecologically representative” – meaning that they encompass myriad ocean biomes – and that the networks of MPAs be “well-connected”, rather than existing in isolation.

It also includes calls to “support food security and other socioeconomic objectives, including the protection of cultural values”, and to support developing states. The section makes no mention of fish or fishing, nor does it address destructive seabed activities, such as mining.

As laid out in the new treaty, parties to the treaty will be able to present proposals for new area-based management tools and MPAs. The text lays out 10 “key elements” that a proposal must contain, including a draft management plan.

These proposals would undergo a preliminary review by the scientific and technical body, then opened to consultation from “all relevant stakeholders” in a manner that is “inclusive, transparent and open”. The submitting party will then be asked to “revise the proposal accordingly or respond to substantive contributions not reflected in the proposal”.

If a party objects to the establishment of an MPA during the 120-day review period mandated by the treaty, the party will be exempted from the MPA.

The treaty provides three potential justifications for a party to object: the decision infringes on the rights or duties of the party with regards to the convention; the decision discriminates against the party; or the party cannot reasonably comply with the decision.

A party must renew its objection every three years and is not supposed to act in a way that undermines the MPA, if possible.

Currently, only about 1% of the high seas are protected.

The world’s first MPA outside of national waters was the South Orkney Islands southern shelf MPA, which covers nearly 100,000 square kilometres (km2) of the Southern Ocean. It was established in 2009 and prohibits commercial fishing, although it is allowed for “research activities”, with permission.

The first network of MPAs outside of national jurisdiction was established in the northeast Atlantic Ocean in 2010. This network of six MPAs spans nearly 290,000km2.

The treaty itself does not set out any specific targets for the amount of ocean that “should” be protected; rather, it establishes the legal mechanism by which such protected areas can be established.

Villagomez tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s not a guarantee that MPAs will happen, or that fisheries restrictions will happen, or that there will be restrictions to mining. But what it does do is create a mechanism for them all to be addressed in the same place.”

Environmental impact assessments

Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) were another element of the treaty for which negotiations came down to the wire.

It was only on 2 March that parties had a “breakthrough” and were able to agree on issues such as thresholds for conducting an EIA, how countries would screen projects, deciding on state-led versus COP-led decision-making, and how other parties’ concerns would be dealt with.

During the final plenary, right after announcing that the text had been accepted, IGC president Rena Lee immediately clarified:

“It should be noted that parties are of the view that environmental impact assessments shall be state-led. In order to promote transparency, there are provisions which allow another party to register its views on the impact of a planned activity and for the scientific and technical body to make non-binding recommendations.

However, the parties’ understanding is that the state decides whether an activity is under its jurisdiction or control.”

The section on EIAs forms the longest part of the treaty. It comprises 13 articles that set out its objectives and establishes guidelines and standards for how EIAs will be conducted, monitored, reviewed and governed by parties as well as the COP for areas both beyond and within national jurisdictions.

Not only is it the longest part, but it also took up many hours of negotiation time at the resumed fifth session. This was because this section will enable the review of environmentally harmful and polluting projects both outside and inside of national boundaries meaning that the treaty’s standards might overshadow existing national processes.

Discarding three longer definitions in earlier drafts, the treaty defines EIAs as “a process to identify and evaluate the potential impacts of an activity to inform decision-making”.

It additionally defines “cumulative impacts” to include the “consequences of climate change, ocean acidification and related impacts”.

Conducting EIAs for cumulative and deep-sea impacts, besides others, can be prohibitively expensive and require technology and expertise.

Dr Sharifah Nora Asfiah Binti Syed Ibrahim, senior lecturer at the Universiti Malaysia Sabah and the Borneo Marine Research Institute, tells Carbon Brief:

“Developing countries are burdened with the costs of screening and EIAs for activities under their jurisdiction that may impact areas beyond national jurisdiction. In addition, they have to bear other costs, such as the annual assessed contribution towards running the Secretariat, COP meetings, running crucial subsidiary bodies and their meetings, the clearing-house, databases and other platforms. All the above also requires capacity-building and technology for the effective participation of developing countries. But the benefit sharing and funding mechanisms under this treaty are vague and inadequate.”

The EIA section of the treaty looks to build the capacity of developing countries, particularly of least-developed countries, small-island developing states and coastal African states, in conducting and evaluating EIAs and “strategic” EIAs (see below).

When a country plans an activity within its territory that it thinks “may cause substantial pollution of or significant and harmful changes to the marine environment in areas beyond national jurisdiction”, it must ensure that it conducts an EIA – either under its national process, or as per this section of the treaty.

If it does so under its national process, it must inform the COP via the clearing-house mechanism in “a timely manner” during the process and ensure monitoring of the activity. It must also make all information, including EIA reports and monitoring reports, available via the clearing-house mechanism.

At this stage, the scientific and technical body can choose to send comments to the country in question.

Deciding the thresholds that necessitate conducting an EIA were the subject of much dispute in the negotiations.

If a project might cause “more than a minor or transitory effect on the marine environment”, or if “the effects of the activity are unknown or poorly understood”, states must conduct an initial “screening” that has to be “sufficiently detailed”.

This means providing a description of the activity in question: its purpose, duration, location and intensity – followed by an initial analysis of potential impacts, including cumulative effects.

Based on this, if the state determines that the activity will cause “substantial pollution” and “harmful changes to the marine environment”, an EIA will need to be conducted.

Both this determination and analysis need to be made available to the COP and other parties via the clearing-house for them to assess and comment on.

The treaty asks countries to adopt and implement the standards and guidelines it develops in their own legal instruments and in other global, regional or sectoral bodies they might be a part of.

It also asks the COP to develop mechanisms to collaborate with other legal instruments and bodies that “regulate activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction or protect the marine environment”.

The treaty allows countries to skip this screening process or EIAs for projects in areas beyond national jurisdiction. But, to do so, they must decide that impacts have already been sufficiently assessed under other laws or frameworks by other “global, regional, subregional or sectoral bodies” with standards equivalent to the treaty and that are designed to prevent, mitigate or manage potential impacts.

Within 40 days of a party publishing their screening and their determination, other parties can register their views on potential impacts. The scientific and technical body can consider them and make recommendations to the country in question.

Additionally, it enables countries to conduct joint EIAs, “in particular for activities under the jurisdiction or control of small island developing states”.

The scientific and technical body will also create and maintain a roster of experts to assist countries which lack the capacity to conduct and evaluate screenings and EIAs for activities under their control.

The inclusion of an article on “strategic” environmental assessments was celebrated as a “win” for being forward-looking and taking in cumulative aspects.

A strategic environmental assessment is a “higher-level assessment” that can be undertaken by a party, or jointly, to examine potential impacts from government policies and programmes on the marine environment beyond their national jurisdiction.

It can also be conducted by the COP to assess an area or region to “collate and synthesise the best available information, assess current and potential future impacts and identify data gaps and research priorities”.

A specific section on assessing transboundary impacts was deleted from the final draft. However, “transboundary impacts” are part of the criteria developed for proposals identifying marine protected areas.

Decisions on EIAs and determining whether they need to be conducted will, ultimately, fall on parties. One expert tells Carbon Brief that “it is scary” that any country can determine via scoping and screening that they do not need to assess environmental impacts.

Capacity-building and technology transfer

Capacity-building and technology transfer “is underpinning all topics of the convention”, Coelho, the Brazilian lawyer, says. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Implementation [is] dependent upon countries having the capacity and the technology to implement [the treaty].”

The stated purpose of the treaty’s section on capacity-building and technology transfer is to support developing states in achieving the objectives laid out in the marine genetic resources, area-based management tools and environmental impact assessments sections.

The transfer of marine technology is already addressed in UNCLOS itself, in Part XIV. But, Coelho points out, this is part of the convention that has the “biggest gap of implementation”.

The new treaty calls for “full recognition to the special requirements of developing states”. It also ensures that this capacity-building “is not conditional on onerous reporting requirements”, a provision that some delegates had opposed.

The treaty also makes clear that the technology transfer in question is to benefit developing states, precluding the situation in which developed countries transfer technologies to one another. It also lists the groupings of states that should receive the most attention: “The least-developed countries, landlocked developing countries, geographically disadvantaged states, small-island developing states, coastal African states, archipelagic states and developing middle-income countries.”

One issue that featured in several rounds of the negotiations was whether technology transfer would occur on a strictly voluntary basis, or whether there would be a mandatory component as well. The final treaty avoids specific language around voluntary and non-voluntary contributions.

The treaty also establishes a committee to oversee capacity-building and the transfer of marine technologies.

This committee, which will report and make recommendations to the COP as a whole “periodically”, is charged with assessing the needs of developing states, identifying gaps in the support mobilised, measuring performance and making recommendations for follow-up. It is also responsible for “identifying and mobilising funds”.

This link between the monitoring framework and the financial mechanism is “crucial”, Coelho says. She adds:

“By doing that, we can ensure that there will be funds, that there will be financial resources to promote capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology. Because we can have all the beautiful law, but if we don’t have funds…this will be another white elephant.”

Dr Katy Soapi, the coordinator of the Pacific Community Centre for Ocean Science, points out that capacity-building and technology transfer is not just key to implementation, but to ensuring that developing countries can both comply with and benefit from the treaty. She tells Carbon Brief:

“We have limited capacity, know-how and scientific data, and access to capacity development and technology transfer can go a long way in addressing these needs and bridging the gap.”

An annex to the treaty also provides a non-exhaustive list of modes and methods of capacity-building and technology transfer.

Among these are: the sharing of relevant data and research; raising awareness of stressors, such as climate change and ocean acidification; developing infrastructure; strengthening regulatory frameworks and mechanisms; and funding the development of technical expertise.

The section on capacity-building and technology transfer was the first main area of the text to be cleared of areas of disagreement during the final negotiating session. Coelho says:

“I think it shows, first of all, the good work of the facilitator. And, secondly, that countries really agreed upon the necessity and the language. I think it really highlights commitment.”

Ismail Zahir, Samoa’s adviser for oceans and sustainable development, tells Carbon Brief:

“When you look at the high seas, all the marine research and scientific work that is being done currently is mostly by the global north, mostly through our ports and even within our exclusive economic zones. The best we get normally is just like a person from the country on the vessel just to observe. There’s no meaningful capacity or institutional capacity that’s being built under UNCLOS.

“This treaty is a great way to start bringing more equity and parity. If we have this capacity and technology, it will give us a lot of co-benefits in terms of our ability to utilise our genetic resources within our national jurisdictions, as well.”

Marine genetic resources

Long believed to be a marine desert, the deep sea is anything but: it is teeming with unique life forms that have adapted their biochemistry to thrive under high pressure and very little oxygen and light.

The ocean’s depths are a vast source of genetic diversity that could potentially be useful to humans. It is a growing area of research, but skewed in favour towards those with resources and technology to scour the deep sea in the race to find new sources of chemical diversity.

Most of the deep sea is in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), which complicates the already-complex issue of who gets to access marine genetic resources, who claims rights over them and who derives benefits.

The subject can pit coastal countries and local communities that need support for conservation against industry and rich countries that can afford to, say, send submersibles to the seafloor and commercialise their discoveries.

It can also challenge academia’s open-access objectives because open-access libraries of digital sequence information, if not tagged correctly and supported by law, can deprive countries and communities of benefits.

Some researchers point out that it could take a significant time for financial benefits from MGRs to flow. Others point out that drugs developed via marine-genetic technology have already generated significant revenues and should, therefore, be used to provide a contribution to the conservation of deep-sea biodiversity.

At the resumed IGC5, developing countries, especially the African Group, insisted that the treaty should guarantee an access-and-benefit sharing mechanism for marine genetic resources, similar to the one set up at COP15 which also covers Digital Sequence Information (DSI).

By the penultimate day of the talks, developed countries were not opposed to the idea of such a mechanism, but there were still concerns about the “how, where, when and how”.

Dr Joachim Claudet, a researcher at the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris, tells Carbon Brief:

“Many of us knew from the beginning that marine genetic resources would be problematic…in terms of who should put money there, how much how would be calculated, the amount of money the other country would get [and] is it before use and development of patents or based on actual benefits…It’s very technical and it’s about money, in the end. So it’s complicated.”

As happened at COP15 last December, countries agreed to develop a multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism, including a global fund. But there is still ambiguity around the familiar questions of who should pay and how monetary and non-monetary benefits will be distributed.

Article 11 covers both monetary and non-monetary benefits from MGRs and their digital sequence information.

Non-monetary benefits include access to all samples, digital sequence information, open access to scientific data, increased scientific and technical cooperation and transfer of marine technology and capacity-building, such as by financing research programmes in developing countries.

Monetary benefits “shall be shared fairly and equitably…for the conservation and sustainable use of the marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction”. These are spelt out in the financial mechanism. (See: Finance)

In order to receive benefits, samples need to be tagged carefully so their sources of origin can be identified. Experts tell Carbon Brief that a key gain in these negotiations is the “BBNJ standardised batch identifier”, which has been operationalised in Article 10.

If a party plans to collect marine genetic material from its original site, it must notify the treaty’s clearing-house mechanism “as early as possible”, or at least six months prior.

This should include information on:

- The nature or objectives of collection.

- The subject matter of research, the MGRs to be collected (if known).

- Geographical information.

- Methods and means of collection, including details about vessels and equipment used.

- Date of first deployment and departure.

- Project leadership and sponsor details.

- Opportunities for scientists of all countries, in particular for scientists from developing countries, to be involved in or associated with the project.

- A data management plan.

When parties upload this information, the clearing-house will automatically generate a BBNJ standardised batch identifier.

Thambisetty says this identifier was a “key gain” from the negotiations, where some countries suggested early on that certain genetic material could not be traced or tagged. She explains:

“This [identifier] will allow for samples to be tagged when collected, with a cascading effect through the obligations to share benefits. As a treaty measure, it is the sort of practical solution that developing countries have been seeking for governance of biodiversity for decades. Hopefully, the conversation will now shift globally to asking how we should trace the origin of genetic resources, not if we should do so.”

Countries are also expected to report on publications, patents granted and products developed from marine genetic resources and their genetic data, along with information of sales of relevant products.

Experts have pointed to a concerning lack of a definition of fish, fishing and fishing-related activities in Article 1.

According to Dr Sharifah Nora, since the treaty links to other global instruments, such as the World Trade Organisation or the Agreement on Port State Measures – which both have very wide definitions of fish, this could potentially undermine the treaty. For instance, the Port State Measures Agreement defines fish as “all species of living marine resources, whether processed or not”.

She warns:

“This could exclude all of the living marine resources from BBNJ regulation, leaving not many marine genetic resources as sources of benefit sharing.The draft text concedes too much to the fishing lobby, which has huge and detrimental effects to the objectives of the treaty.”

Marine genetic resources are the only section that mention “fish” and “fishing-related activities” – but only to exempt them from its provisions.

Other observers, such as Clark, say that there was “a big push to have fish excluded from the entire agreement” and that wording around fish and genetic resources was “about the best we could expect”.

What has the reaction been?

Many scientists, policy experts, NGOs and politicians welcomed the successful conclusion of the negotiations.

A spokesperson for UN secretary general António Guterres said in a statement that the final text “marks the culmination of nearly two decades of work” and called it a “victory for multilateralism”. The statement continued:

“It is crucial for addressing the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. It is also vital for achieving ocean-related goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.”

Dr Siva Thambisetty tells Carbon Brief that “we can all be proud of what we achieved here”. She says:

“The treaty has the components of an equitable solution for the monetary and non-monetary sharing of benefits arising from marine genetic resources and digital sequence information. Challenges may arise if countries use the flexible language they pushed for to create a race to the bottom of regulatory burdens. Good-faith engagement and cooperation will be essential to ensure that benefits flow in ways that capture the intent and goodwill all parties showed in the process.”

Dr Sharifah Nora tells Carbon Brief:

“The global north treats the treaty as a tool to implement the 30×30 concept of the non-legally binding Global Biodiversity Framework, by planning to establish huge marine protected areas in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The global south is expecting the treaty to be both for conservation and sustainable use with fairness and equity, an agreement that clearly recognises the resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction as being the common heritage of humankind.”

Dr Katy Soapi tells Carbon Brief:

“Although negotiations were challenging, tremendous effort was made to find common grounds and arrive at agreed positions. I think everyone has something they are happy with and some big wins for developing countries especially on country-driven capacity, transparent, effective capacity development and needs assessment and support toward that.”

But, she adds, “it remains to be seen how effective the implementation will be in practice”.

Angelo Villagomez praised the dedication of the delegates, some of whom had been working towards this treaty for nearly two decades. He tells Carbon Brief that the treaty “is a great step in the right direction, towards better management on the high seas, which has been a wild west for a very, very long time”.

He also points out the lack of inclusion of Indigenous voices during the process, saying that “at the same time, there were no Chamorros at the table”, nor members of other US Indigenous groups.

Villagomez tells Carbon Brief:

“Colonised peoples are not being represented at these international discussions. Even at national discussions, we’re often not represented…We may agree and we may disagree [with the outcomes of the negotiations]. But the bigger problem is that we don’t have a seat at the table.”

This was not the only criticism of the process.

The resumed fifth leg of negotiations drew more than 400 delegates from national governments, non-profits, academia and UN agencies to the UN Headquarters in New York. Other than the plenaries, which were webcast, most of the negotiations happened behind closed doors.

Many participants and delegations complained of small meeting rooms for the actual negotiations. “Bigger rooms in UN were allocated to EU coordination meetings while BBNJ suffered”, said one observer, a move “specifically to reduce civil society participation”, pushing even delegations to sometimes limit their size to “one or two members max”.

Civil society observers spent two nights in a row in the UN’s halls as presidential consultations continued on the thorniest subjects.

Delegates commented on “negotiation by fatigue” as one way of reaching agreement. In a penultimate plenary, Russia suggested that the meeting come to a close and reconvene at another date if a result could not be arrived at in 30 minutes, while the EU suggested parties wait because of the logistical costs and “pollution” that would result from another meeting.

Extended hours meant that translators, too, had to leave the rooms at different points of time in the middle of crucial negotiations, leading to questions about the inclusivity of the process and whether non-English speaking countries had fully parsed complex legal texts.

Some delegates tell Carbon Brief that they had not even seen the final version of the text that was agreed to in the final hours.

Shortly after the minutes-long applause at the final plenary, some countries also made their objections known. Russia wanted its objection to the working methods registered, while Nicaragua pointed to inequities throughout the process, which they said “did not guarantee equality, equity, balance and transparency”. Nicaragua’s delegate also pointed to multiple parallel meetings that made it “difficult for small delegations to participate”.

One delegate tells Carbon Brief that they were “pleasantly surprised” that final interventions responding to the agreement were mostly just procedural and that they were expecting “certain countries” to be more disruptive.

Cuba’s Richard Tur, lead negotiator for G77+China, thanked president Lee in a heart-felt final intervention. He said:

“If it wasn’t for your kindness, your pureness and spirit, this process would not have been possible. Today, we faced challenges that were unexpected and still we got the result. We always said we were going to deliver and we delivered. Thank you, madam chair.”

Many of the experts that Carbon Brief spoke to made it clear that the treaty was a significant step towards improving ocean health – but that there was still lots of work to be done.

Ismail Zahir says that the delegates “demonstrated really good solidarity” throughout the final hours. He adds:

“At the end of the day, we [small island developing states] are under threat and we do need to take action and this is just the starting point. Even if the text is agreed, there’s still a long way to go before we can start taking actions under this treaty. Time is of the essence and we were very keen to make sure we did whatever it took [to get a treaty].”

-

Q&A: What does the ‘High Seas Treaty’ mean for climate change and biodiversity?