UK could become ‘net zero by 2050’ using negative emissions

Daisy Dunne

09.12.18Daisy Dunne

12.09.2018 | 12:01amThe UK could cut its emissions to “net-zero” within the next three decades by stepping up investment into technologies that can remove CO2 from the atmosphere, a report finds.

However, such methods, which are known collectively as “negative emissions technologies” (NETs), would only be effective if paired with drastic efforts to cut the UK’s current rate of emissions, the findings suggest.

The report, published jointly by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering, evaluates how the UK could capitalise on a range of proposed techniques from “natural climate solutions”, such as planting forests, to more experimental methods, including capturing CO2 directly from the air.

The findings show that the UK “must act quickly” to ramp up “research and investigation” into a suite of NETs, the report’s chair told Carbon Brief at a press briefing in London.

Hitting zero

Under the Paris Agreement, countries pledged to limit global warming to “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

To keep to this limit, countries will collectively need to reach “net-zero” emissions – a scenario where the total amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere is balanced by the total amount taken out – by sometime in the second half of this century.

For the UK to achieve such a target, it will need to “prioritise rapid cuts in greenhouse gas emissions” – largely through the adoption of low-carbon sources of energy, construction and food production, according to the authors of the report, which was commissioned by the UK government’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

However, for some industries, such as aviation and agriculture, it will be almost impossible to cut emissions down to zero, says Prof Corinne Le Quéré, a report author and director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia.

In the video below, she explains why the use of NETs could be necessary to counteract the “emissions we don’t know how to bring down to zero”.

Negative mix

The 133-page report assesses the potential carbon storage of a wide range of proposed NETs, as well as their potential co-benefits and risks.

This information has been used to create a scenario for the UK in 2050 whereby a suite of NETs are used to reach net-zero emissions.

![]()

The UK currently emits around 450m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) a year. Under the Climate Change Act, the UK is committed to an 80% reduction in emissions by the year 2050, relative to 1990 levels.

However, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) – the independent body that advises the government on climate policy – has suggested that, if efforts to reduce emissions are increased, the UK could exceed this target. This would lead to annual emissions of 130m tonnes of CO2e by 2050.

The new scenario assumes that the UK does manage to slash its emissions and that a mix of NETs are used to balance out the remaining 130m tonnes of CO2e in 2050.

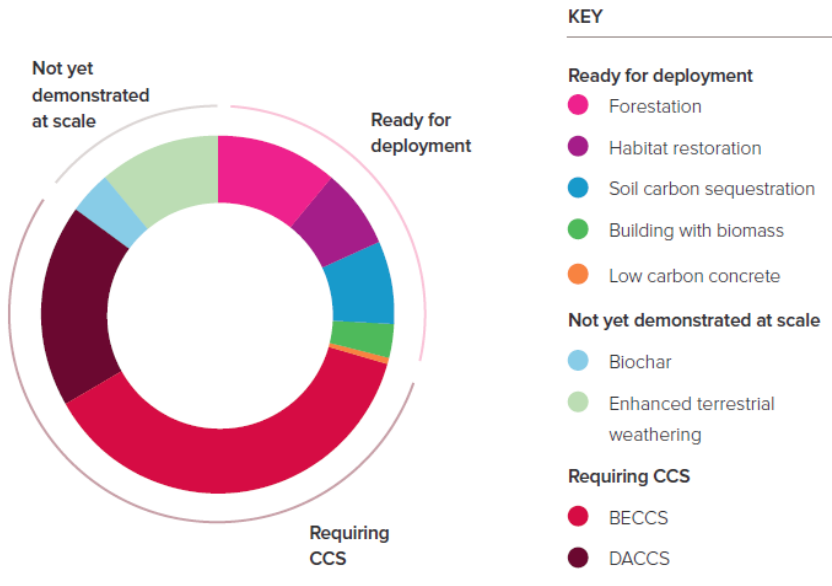

The chart below shows the expected relative contributions of nine techniques. The first five are grouped into “ready to deploy” methods, such as planting forests (pink), restoring habitats such as peatlands and wetlands (purple), enhancing the amount of carbon stored in the soil (blue), building with wood – or “biomass” (green) and using low-carbon concrete for construction (orange).

The potential of various technologies to offset UK emissions (in millions of tonnes of CO2e) in 2050. Proposed technologies include forestation (pink), habitat restoration (purple), soil carbon sequestration (blue), building with biomass (green), low-carbon concrete (orange), biochar (pale blue), enhanced weathering (pale green), bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS; crimson) and direct air capture and storage (DACCS; brown). Source: Royal Society & Royal Academy of Engineering

The scenario envisages that these “ready to deploy” techniques will be rapidly rolled out across the UK – taking up around 35m tonnes of CO2e, just over a quarter of the UK’s total annual emissions, by 2050.

The rapid deployment of these “natural” techniques would cause considerable land-use change, according to the report.

For example, the scenario assumes that the UK will plant an additional 1.2m hectares of forest – an area roughly the size of the West Midlands. Many of these forests would be monocultures made up of species such as willow or poplar, the scientists told the press briefing.

However, this group of techniques could also come with considerable co-benefits, the scientists added. For instance, increasing the carbon storage potential of the UK’s peatlands and wetlands through habitat restoration could boost natural flood defences and provide more space for native wildfire, the report shows.

Chemical cooling

The second group on the diagram includes two technologies that are “not yet demonstrated at scale”. These are “enhanced weathering” (pale green) – a process where silicate rocks are spread over soils in order to boost the natural process of weathering, which causes CO2 to turn into solid bicarbonate – and the use of “biochar” – a carbon-rich charcoal which, when sprinkled on land, can boost soil carbon storage.

The scenario suggests that these two techniques could offset 20m tonnes of CO2e (or 15% of the UK’s total emissions) by 2050 – with enhanced weathering accounting for three quarters of this figure.

To be effective, biochar would need to spread over a quarter of all of the UK’s arable land, the report says, while enhanced weathering would need to be undertaken on just under a quarter of all arable land.

The two techniques would need to be applied separately, the report adds, meaning that, together, the methods would need to be applied to just under half of all of the UK’s croplands.

The report notes that both methods are at a “low-level of technology readiness” and that their contribution to offsetting emissions could grow larger in the second half of the century. For enhanced weathering, around two thirds of the silicate rock needed could be provided by waste materials from the industries including cement and steel, the report adds.

Capturing carbon

The last set of technologies are labelled “requiring CCS [carbon capture and storage]”. There are two of these – direct air capture with carbon capture and storage (DACC; brown on the diagram) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS; crimson on the diagram).

DACC involves using machines to directly “suck” CO2 out of the air and then store it underground. BECCS involves burning crops to create bioenergy, capturing the resulting greenhouse gas emissions in a power plant and storing them underground.

The scenario assumes that these two technologies will offset 75m tonnes of CO2e – almost 58% of the UK’s total emissions – by 2050.

However, the report acknowledges that “neither BECCS nor DACCS have yet been demonstrated to operate at a large scale” and that the development of CCS will be key for the UK to meet its emissions targets. In the report, the authors say:

“Crucially, meeting the UK target, therefore, depends on rapid development of the carbon transportation and storage infrastructure required for CCS.”

A major barrier to the development of CCS is the cost associated with directly capturing CO2 from the atmosphere.

The report shows that, if deployed, BECCS could require around 1m hectares of UK land – largely farmland – to be converted into biomass plantations. This could have consequences for biodiversity and food security, according to the report authors.

Political will?

To reach the scenario outlined in the report, the UK will need to “act quickly” to boost investments in negative emissions research, says Prof Gideon Henderson, chair of the report working group from the University of Oxford. At the sidelines of the press briefing, he told Carbon Brief:

“The report makes it clear that we would need to act quickly, we would need to ramp up reforestation. In the slightly longer term, we would need to develop technologies that are somewhat unproven, such as biochar. We need research and investigation into those techniques now so we’re ready to pursue them in the coming decades. We also need to establish – as soon as we can – CCS infrastructure and scale that up, so that we’re ready to store the CO2 that is extracted using future techniques.”

Scaling up NETs would also require changes to UK policy, the researchers say. For example, increasing the price on carbon would be “necessary” to make CO2 removal economically feasible, the report finds.

In addition, the government will need to introduce more incentives for techniques such as afforestation and enhancing soil carbon stocks.

On Tuesday (11 September), Conservative MP Simon Clarke handed in a letter to the government – backed by 132 MPs and 51 peers – calling for the UK to adopt a net-zero emissions target before 2050.

In a press statement, Clarke said: “To bring our climate back into balance we have to finally end our emissions. We have led the world in confronting this problem and can lead in solving it, drawing on our engineering and scientific prowess that will help bring us to net zero.”

Update: The original headline has been amended to say “net zero” rather than “carbon neutral”.

-

UK could become ‘net zero by 2050’ using negative emissions

-

Negative emissions could enable UK to reach 'net zero by 2050