Roz Pidcock

30.04.2014 | 4:00pmIn the UK, the probability of seeing an extremely wet winter like we did this year is 25 per cent higher than it was before humans started influencing the climate, scientists announced at the European Geosciences Union conference today.

The study’s conclusion isn’t the only noteworthy thing about it, however – the research was done almost entirely with the help of members of the public.

Record-breaking winter

Just two months after the flood waters began to subside, an Oxford University project assessing global warming’s effect on the odds of very wet winters has produced its first results.

The scientists found greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of human activity have increased the risk of extreme rainfall in the southern part of the country by about 25 per cent.

Total rainfall (mm) for January in southern England from records going back to 1910.

Official Met Office figures show this year saw the wettest January and wettest winter in England and Wales in at least 248 years, when records began.

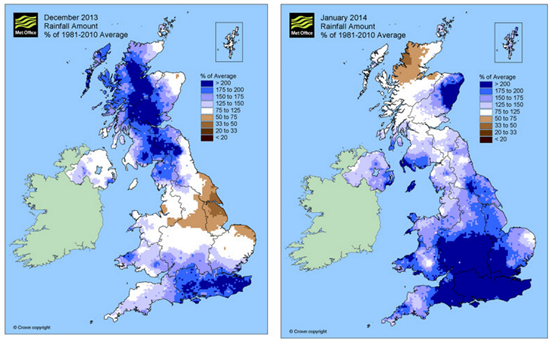

In January, parts of the southern England received more than 200 per cent of the average rainfall for the month – shown in dark blue in the maps above.

Citizen science

The weather@home project, supported by The Guardian, is an example of what’s known as ‘citizen science’. That’s where members of the public dedicate some time and resources to collecting or processing scientific data.

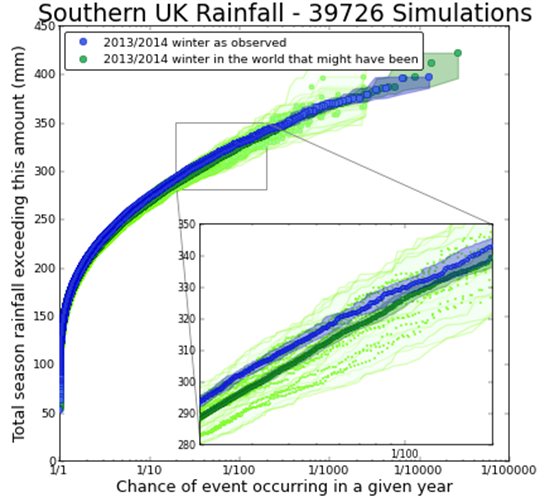

More than 60,000 volunteers offered spare capacity on their home computers for scientists to run model simulations. The simulations compared rainfall projections in a world influenced by past greenhouse gas emissions with a hypothetical world with no human influence on the climate.

Comparing the number of extremely wet winters between the model simulations allowed an estimate of how much more likely an event like we saw this winter has become due to greenhouse gas warming.

One in 80-year event

The scientists found an extreme rainfall event that would normally happen once every 100 years (i.e. there’s a one per cent risk of it occurring in any given year) is now happening more like once in 80 years (or a 1.25 per cent risk). In other words, the risk of a very wet winter has increased by 25 per cent.

The graph below of seasonal rainfall in mm shows the difference between the dark blue “winter as observed” and the dark green “winter in the world that might have been”. The difference is “small but statistically significant”, say the researchers.

In total, the team ran more than 33,000 model simulations – something project leader Myles Allen says they simply wouldn’t have been able to do without enlisting the help of the public.

The scientists point out they used a range of different climate models and not all gave the same result. In some cases, models showed no change in risk or even a reduction. But overall, the simulations showed a small but significant increase in likelihood of extremely heavy rain events for the south of England.

Coming just two months after heavy rainfall and flooding hit the UK, these results have been produced in next to real-time. That’s a remarkable achievement and testament to the ability of this type of crowdsourcing work, Allen told a press conference at the EGU meeting today.

And these are still just early days for the project. In the next few months, it’s hoped the results can feed into impact models to put an estimate on the likely material and economic damage from such extreme events, Allen tells Carbon Brief.

Dr Friedereke Otto, a researcher at Oxford University who was involved with the weather@home project explains:

“Total winter rainfall, although useful as a benchmark, is not the direct cause of flood damage, so we are working with collaborators, such as the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, to explore the implications of our results for river flows, flooding and ultimately property damage.”

Loading the dice

Last September, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a bumper assessment of how and why the climate is changing. It concluded that Europe and the UK is “very likely” to see more heavy rainfall events by the end of the century.

Heavy rainfall and flooding can disrupt important transport links, something we saw a lot of in the UK the this winter.

As temperatures rise, basic physics dictates an increase in the amount of atmospheric moisture, which is the fuel for heavy rainfall events. That means whenever we have heavy (and prolonged) rainfall events in the future, we can expect them to be more intense.

Otto said greenhouse gas emissions have “loaded the weather dice”, so the probability of extremely wet winters has slightly increased. Otto adds:

“It will never be possible to say that any specific flood was caused by human-induced climate change. We have shown, however, that the odds of getting an extremely wet winter are changing due to man-made climate change.”

Heavier rainfall plus sea level rise – which make storm surges bigger and more likely to breach coastal defences – has scientists warning of a greater flood risk in the UK as the climate warms.