In-depth: UK pledges coal phase out by 2025, but uncertainty remains

Sophie Yeo

11.19.15Sophie Yeo

19.11.2015 | 12:38pmThe UK has announced its intention to close all unabated coal-fired power stations by 2025 and restrict their usage from 2023.

The declaration came as part of Amber Rudd’s much-anticipated “reset speech”. This promised to begin a new phase in energy policy, after the energy and climate change secretary reduced subsidies for renewable energy earlier this year.

This new deadline for the UK’s most carbon-intensive energy source has been largely welcomed by campaigners and analysts. However, concerns and questions remain about what will replace coal.

“It is significant that the country that led the industrial revolution is the first major economy to set a date for the phase out of unabated coal,” said Nick Mabey, chief executive of climate and energy think-tank E3G. “But if coal is simply replaced by gas the UK will continue its addiction to fossil fuels and is in danger of being left behind in the global clean tech race.”

Coal phase-out

Speaking in London on Wednesday, Rudd said that the government will launch a consultation in the spring on when to close all coal-fired power stations in the UK that are not able to capture and store their emissions.

“Our consultation will set out proposals to close coal by 2025 — and restrict its use from 2023. If we take this step, we will be one of the first developed countries to deliver on a commitment to take coal off the system,” she said.

The UK has 11 remaining coal power stations, which supply 30% of the UK’s electricity.

But the role of coal is declining, both in terms of production and demand.

In 2014, government figures show that domestic coal production decreased by 8.1% on 2013 levels to an all-time low of 12m tonnes, while imports were 15% lower than 2013 at 42m tonnes. Demand for coal decreased by 20%, from 60m tonnes in 2013 to 49m in 2014. Last year, around 79% of the UK’s demand for coal – 38m tonnes – was from major power producers for electricity generation.

Role of gas

The promise of a coal phase out by 2025 comes with a significant caveat, however.

Rudd stressed that the space left by the demise in coal should be filled by gas — less polluting than coal, but a carbon dioxide-emitting fossil fuel no less. She said:

Let me be clear, we’ll only proceed if we’re confident that the shift [from coal] to new gas can be achieved within these timescales.

Rudd promised that this switch would be “one of the greatest and most cost-effective contributions we can make to emission reductions in electricity”.

Indeed, the promised coal phase out is contingent upon a shift to gas being possible within the 2025 time scale, Rudd added.

Many observers criticised this approach, suggesting that it was neither cost-effective, nor consistent with meeting the UK’s legally binding climate targets.

![]()

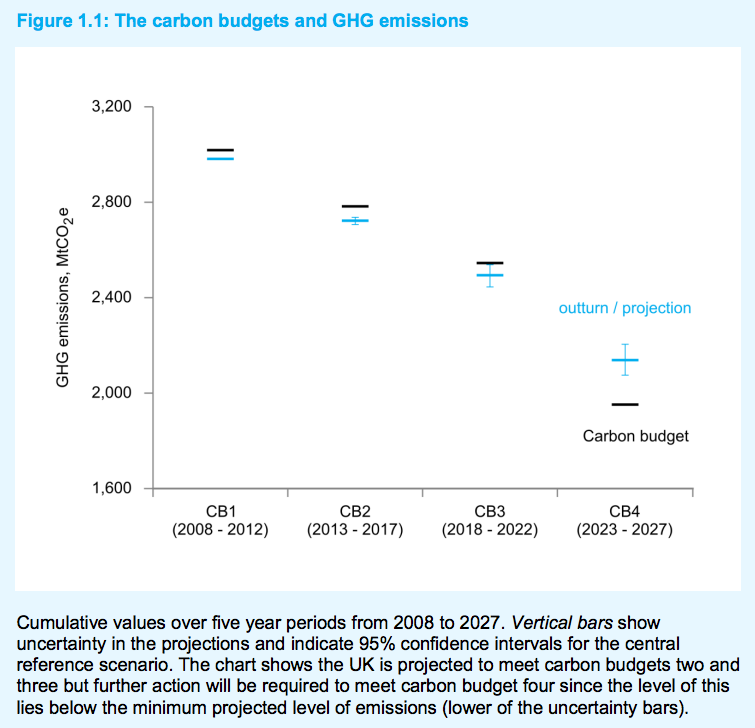

Rudd said that the government is committed to meeting the challenge of its carbon budgets and will set out further policy details next year. However, she failed to mention new analysis released by DECC yesterday, showing that the shortfall in meeting the fourth carbon budget (covering the period 2023-27) has risen from 133 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2014’s projection to 187 MtCO2e in this year’s update.

The government says that the increase in its projections is due to methodological changes in how emissions savings from land use are accounted, as well as changes to demographic projections and fossil fuel prices.

Academics have argued that gas is only effective if used as a “bridge” fuel, in the transition to a fully low-carbon future. This means that gas use must fall in the late 2020s and early 2030s, with widespread use only possible after 2035 if its emissions are captured and stored.

Prof Richard Templer, director of innovation at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London, said in a statement:

Replacing coal with gas is a good step, but only in helping us to make a transition to a world in which we no longer use fossil fuel for primary energy production. I am perturbed, therefore, that I cannot see a clear, strategic roadmap that shows how the government intends to use gas as a bridge to a decarbonised electricity supply.

Paul Ekins, professor of resources and environmental policy and director of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, said in a statement that most of the UK’s coal stations would have closed anyway by 2025, and questioned the efficacy of replacing them with gas. He said:

Who will invest in the new gas-fired power stations the government wants to replace coal, after its U-turns on renewables have left so many investors who believed past government policy out of pocket? The government will have to pay dearly for the extra risk these investors will now perceive themselves to be taking, so that its subsidies for gas may need to be higher than those for renewables in the next decade and we will miss our carbon targets. Lose-lose, for the consumer and for the climate. What a shambles.

Capacity versus generation

Nonetheless, Rudd’s speech may not tell the whole story of a coal-to-gas switch. Strong words from the secretary of state will not necessarily precipitate a renewed dash for gas, according to Dave Jones, carbon and power analyst at think-tank Sandbag. He said:

As renewables and new nuclear are built, gas is likely to play a reduced role for power generation in the longer term, regardless of how strong the government rhetoric on gas is today.

Rudd has promised that the government will push for additional gas using the capacity market — a subsidy scheme designed to ensure a secure supply of electricity during the winter.

While this was trailed by the government as a means to incentivise new-build gas capacity, only one large new power station won a contract in the 2014 auction. This was a 1,656 megawatt gas-fired plant at Trafford in Manchester.

Rudd did not specify how the government might structure the auction to ensure that more contracts are awarded to new gas bids in the future.

Nor did she specify whether the caveat attached to the phase-out — that the shift to new gas can be achieved by 2025 — applied to new gas capacity or actual generation.

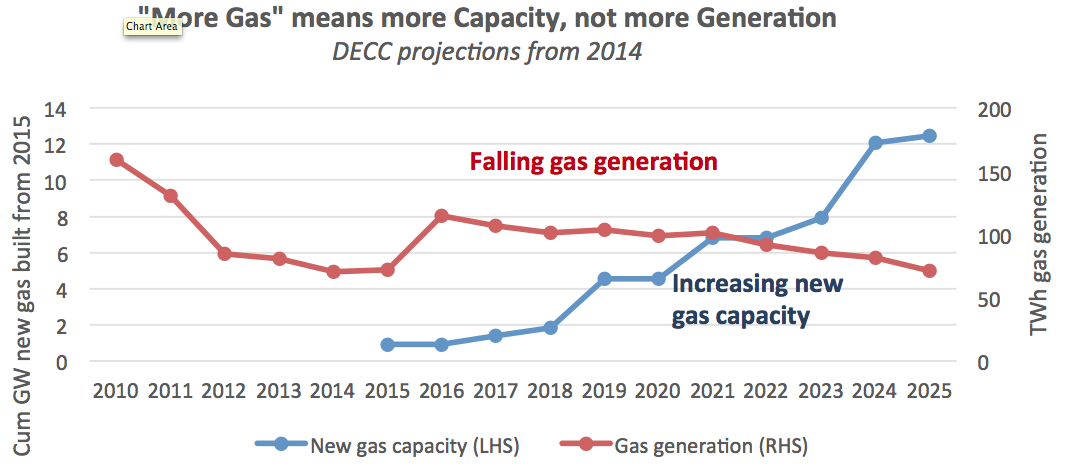

This is relevant because of the Department of Energy and Climate Change’s (DECC) own projections.

In 2014, the department released a scenario where coal falls to 1% of the UK’s energy supply by 2025, similar to the actual target released today.

In these circumstances, DECC predicted that the UK’s gas capacity would indeed rise, ensuring a steady supply of energy when needed. But, at the same time, the projections see actual gas generation falling by more than half between 2008 and 2025, while renewables generation increases by almost seven times in the same period.

DECC projections for UK gas generation and capacity, in a scenario where coal falls to 1% by 2025. Chart by Sandbag

Dave Jones from Sandbag tells Carbon Brief: “So long as renewables continues to be built, we can still see falling levels of gas generation, even with new gas capacity coming online.”

Coal restrictions

Amber Rudd said that, as well as requiring a full coal phase-out by 2025, restrictions would also be in place on the industry by 2023. She did not specify what these restrictions will be, and they will be discussed as part of the government’s spring consultation.

How the government decides to restrict the operation of coal plants will impact the rate at which coal declines in the UK.

There are two precedents for power plant restrictions currently in place that the government could draw on for inspiration.

The EU’s Industrial Emissions Directive offers one model. This allows power plants to adopt less stringent air pollution rules if they agree to limit operations to 1,500 hours a year.

Another method is that employed by the UK’s National Grid. To ensure that there is enough power in the winter, the grid uses a tool called the Supplemental Balancing Reserve (SBR). This means that they pay power stations that would otherwise be closed to instead sit in a reserve, so that they can be called upon in the event of a shortfall.

If the government restricted coal in the style of the latter, it would mean that power would only be generated from coal in emergency situations. This would be a positive approach, Sandbag’s Jones tells Carbon Brief:

To restrict coal use after 2023, we would like to see the coal sit in a reserve, so it would only run after 2023 if it were needed to keep the lights on.

Media coverage

The details on the UK’s promise to phase out coal is just one of many questions raised by Amber Rudd’s much-anticipated reset speech.

The government will also need to provide further details on other statements in the speech, including how it plans to hold the renewables industry responsible for the intermittency of the power that it generates.

The Telegraph reports that ministers have commissioned the consultancy Frontier Economics to examine the “true cost” of renewables, and that DECC is considering how these costs could be reflected. It points out the criticism made by opponents of renewables that if these generators were forced to bear such costs, their competitiveness could be affected.

It also looks at changes to offshore wind subsidies. Amber Rudd has promised that the government will support 10GW of new offshore wind projects in the 2020s, holding three auctions this Parliament, with the first taking place by the end of 2016.

But this is only on the condition that the technology moves to cost competitiveness. “If they don’t there will be no subsidy,” said Rudd. The Guardian points out that this means it must be able to compete with nuclear — a technology that received strong support in the speech.

The Telegraph also looked at the possibility that the National Grid could be broken up and handed to a new independent body, which Rudd suggested in her speech.

An editorial in today’s Guardian says that Rudd’s plan has made the UK’s attempts to reduce carbon emissions harder than it needs to be. The Financial Times said that the “two biggest questions” raised by Rudd’s plans are: “Will enough gas plants be built to make up for the loss of coal power? If so, will climate targets be met?”

But, despite uncertainty, the UK’s decision to phase out coal marks an historic moment. As the first major economy to turn away entirely from the dirty fossil fuel, it could – whilst remembering the caveats noted above – translate into a powerful statement in the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.