Roz Pidcock

13.11.2013 | 4:30pmAs a British aid convoy set out today for the Philippines, the media have posed the question of whether superstorm Haiyan can be linked to rising global temperatures. And some have done a pretty good job of explaining what the science says on this complex topic.

Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines four days ago and is reported to have affected 6.9 million people. Winds reaching 310 kilometers per hour make the storm the most powerful to make landfall since records began.

A warmer world

Tropical storm events are given different names depending on which ocean they form in. Tropical storms are called hurricanes in the north Atlantic and northeast Pacific, and typhoons in the northwest Pacific. Tropical storms are also sometimes called cyclones.

As this Guardian piece describes, tropical storms derive energy from the warmth of the ocean. And the surface ocean is warming. In its latest report, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said the top 75 metres of the ocean warmed 0.11 degrees between 1971 and 2010.

It would seem to make sense that such storms get stronger as the surface of the ocean warms. That’s the theory, at least. But what do measurements of storm activity tell us?

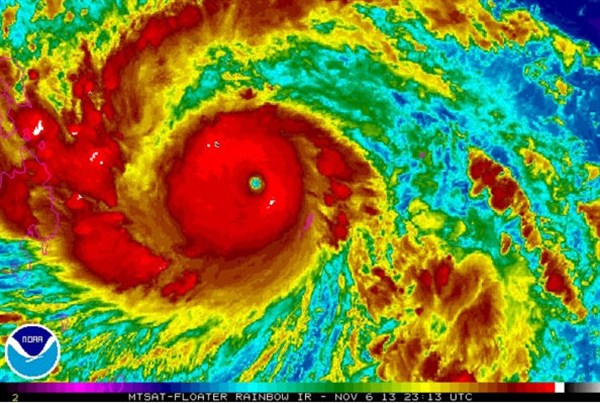

Typhoon Haiyan as pictured in a satellite image taken November 6th 2013. Source: REUTERS/NOAA

A climate change link

Good quality measurements of storm activity are limited largely to the northern hemisphere, which means that globally, it’s not clear whether there have been changes in past trends – or to what extent human activity has contributed.

Despite this, scientists are still able to identify that in certain parts of the world, the intensity or strength of tropical storms has increased – notably the North Atlantic and the western North Pacific, where the Philippines sit. The latest IPCC report noted:

“[Time series combining] tropical cyclone frequency, duration, and intensity â?¦ show upward trends in the North Atlantic and weaker upward trends in the western North Pacific since the late 1970s.”

Detecting trends further back in time is difficult because of inconsistent data coverage before the satellite era, the report adds.

Will storms get worse?

Tropical storm activity is complicated to predict. As this Nature article explains, climate models have trouble representing phenomena like storms, which on a global scale are very small. Instead, scientists have to infer how storms might be affected by much bigger changes in atmospheric circulation patterns.

Predictions need to take into account more than just temperature rise. While warmer seas might stir up stronger storms, changes in the strength and direction of winds could counteract that effect, dampening storm intensity or stopping them forming altogether. So it’s a complicated picture.

On balance, scientists think climate change will bring a shift towards more extreme storms in some oceans, but not necessarily an increase in the total number. In fact, the IPCC suggests it’s likely the frequency worldwide will “either decrease or remain essentially unchanged,” but storms are likely to see stronger winds and heavier rainfall.

Not all scientists agree, however. A recent study by Professor Kerry Emanuel – which was published after the cut off date for the IPCC report – suggests both the frequency and intensity of tropical storms will increase in the 21st century almost everywhere. In the northwest Pacific, where Haiyan formed, the changes are likely to be most pronounced, according to the research.

The IPCC comes to a more muted conclusion – putting the chance of seeing a rise in the number of the most intense storms in the region at 50 per cent.

Attributing a single event

While climate change might mean stronger storms in the future, a blog from the American Geophysical Union does a good job of explaining that no single event can be conclusively pinned to rising temperatures. That’s because scientists can’t be sure if an event would have reached similar proportions in a world that wasn’t warming.

But in a Q & A in The Guardian, Oxford University climate scientist Myles Allen gives an explanation of how scientists have used detailed computer modelling to look back over the last few decades and retrospectively assess the impact of climate change on particular examples of extreme weather – a process known as attribution.

This has let scientists draw conclusions about how the likelihood of different extreme events has been altered by climate change. Allen’s research group has examined examples of heatwaves and heavy rainfall, concluding that climate change tripled the odds of the 2010 Russian heatwave and the 2000 flooding event in England.

But the process is complicated, meaning research is published in peer reviewed journals a number of years after extreme events have occurred. Future efforts will be needed to assess what effect climate change may have had on Haiyan.

Yesterday’s Telegraph reported the Philippines representative at the latest round of UN climate talks in Warsaw, Naderev Sano, blamed climate change for the ferocity of typhoon Haiyan. This Guardian report also says Sano’s speech “clearly linked super typhoon Haiyan to manmade climate change”.

What Sano reportedly said seems a bit more nuanced, talking about the rising probability of storms the size and strength of Haiyan – not what caused Haiyan specifically. He said:

“Science tells us that simply, climate change will mean more intense tropical storms. As the Earth warms up, that would include the oceans. The energy that is stored in the waters off the Philippines will increase the intensity of typhoons and the trend we now see is that more destructive storms will be the new norm.”

Building resilience

Tropical storms follow pathways across the ocean, known as storm tracks. This piece from the blog Grist explains the vulnerability of the Philippines. It says:

“The country’s geography puts its islands in the path of frequent typhoons â?¦ The Philippines’ low and unequally distributed national wealth, meanwhile, leaves its populace highly vulnerable to them.”

The path of typhoon Haiyal through the Philippines, making landfall in Vietnam early sunday morning. Source: Joint Typhoon Warning Centre. Credit: Reuters

A helpful post from WonkBlog looks at the challenges of increasing resilience to extreme weather in less economically developed states. It says that while climate change may play a role in more damaging storms, other key factors are population rise, poverty and poorly constructed buildings.

The second of three reports from the IPCC due in March 2014 will look more closely at these issues and ways vulnerable regions can increase resilience through adaptation, such as early warning systems and sea defences.

The need to rebuild right now in the Philippines is urgent. The BBC reports on the UN aid appeal launched yesterday calling for $300 billion in donations. Bloomberg quotes a statement from the World Health Organisation this week, saying:

“The need for safe water and sanitation facilities is critical”.

In his speech to UN delegates on Monday, Sano urged nations to resolve the deadlock in international climate talks, reports the Guardian. All eyes turn to Warsaw for the next two weeks to see what role Haiyan plays as a backdrop to the talks.