DeBriefed 13 March 2026: War and oil | Why gas drives electricity prices | Japan’s ‘vulnerability’ to Iran crisis

Joe Goodman

03.13.26Joe Goodman

13.03.2026 | 4:53pmWelcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

War and oil

HISTORIC: Leaders from 32 countries agreed to the “biggest emergency oil release in history” in response to the energy crisis sparked by the Iran war, reported Politico. The coordinated release of 400m barrels of oil by member nations of the International Energy Agency (IEA) is “more than twice” the amount released following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the outlet continued.

$100 BARREL: The agreement came as oil surged past $100 a barrel for the first time in four years on Monday, as “traders bet widening conflict in the Middle East would lead to weeks-long supply disruptions”, said the Financial Times. According to a report from the US Energy Information Administration, crude oil prices are likely to remain above $95 a barrel in the next two months, before falling to around $70 by the end of this year, reported Reuters. Research consultancy Wood Mackenzie, meanwhile, said oil prices could yet reach $150 per barrel, according to Reuters.

KREMLIN: The war in Iran has pushed up demand for Russian oil and gas, with the nation making €6bn (£5bn) in fossil-fuel sales in the last fortnight, according to analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air covered by the Guardian. Read Carbon Brief’s Q&A on what the war means for the energy transition and climate action.

Around the world

- FLOODS: A month’s worth of rain in 24 hours triggered floods that killed more than 40 people in Kenya, reported the country’s Daily Nation newspaper.

- NET-ZERO: A new report from the UK’s Climate Change Committee outlined that achieving net-zero by 2050 will have less of a financial impact than the kind of fossil-fuel price rises experienced during the 2022 energy crisis, reported Carbon Brief.

- SOLAR: The amount of solar energy installed in the US fell by 14% between 2024 and 2025, according to an industry report, reported the New York Times.

- WATCHING: A Paris Agreement “watchdog” will discuss this month how to respond to countries who have failed to submit their latest national climate plan, Climate Home News reported, adding that about a third of countries are yet to submit more than a year after the deadline.

99%

The amount by which UK gas production in the North Sea is set to fall by 2050, when compared to 2025, as a result of a long-term decline in the basin.

97%

The amount by which North Sea gas production is set to decline from 2025 to 2050 if the government allows new drilling, according to new Carbon Brief analysis.

Latest climate research

- One-third of the world’s population lives in areas where heat and humidity would “severely limit activity for younger adults” | Environmental Research: Health

- The increase in extreme fire weather over 1980-2023 bears a “clear externally-forced signal” that is attributable to human-caused climate change | Science

- More than 85,000 social media posts from commuters in Boston, London and New York reveal “widespread thermal discomfort” in metro systems | Nature Cities

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

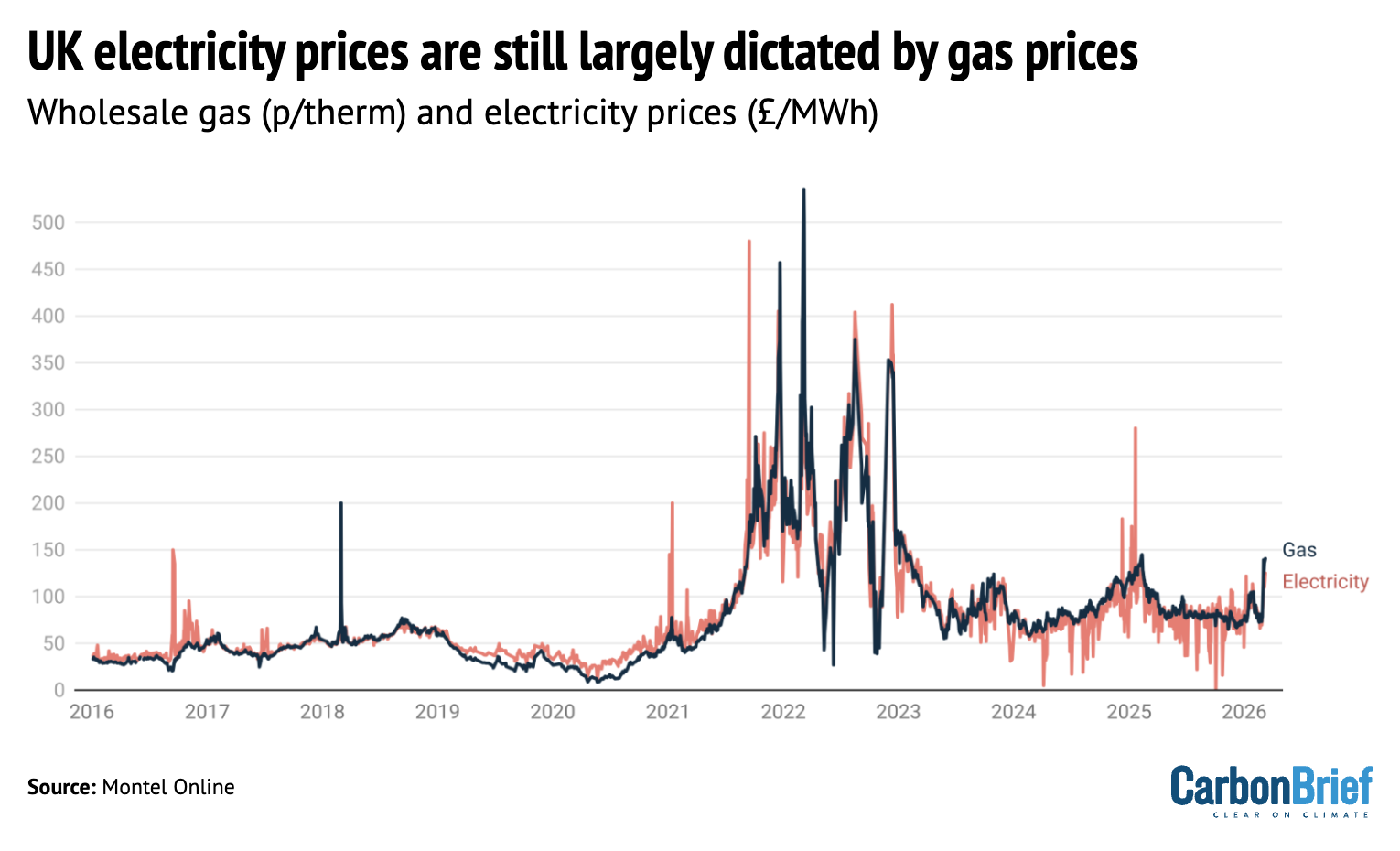

Gas almost always sets the price of power in the UK and many other European countries, due to the “marginal pricing” system used in most electricity markets. A new Carbon Brief Q&A explored why this is the case and whether there are alternatives.

Spotlight

Japan’s ‘vulnerability’ to Iran energy crisis

Carbon Brief talks to experts about the implications of the Iran war for Japan’s energy and economy.

Japan, the world’s fifth largest economy and eighth largest greenhouse gas emitter, is among the countries reeling from the energy crisis fuelled by war in Iran.

Japan’s energy system is “structurally dependent” on imported fossil fuels, making the country “highly vulnerable” to geopolitical shocks, Yuri Okubo, a senior researcher at the Renewable Energy Institute in Tokyo, told Carbon Brief.

Japan currently imports 87% of its energy supply, with the vast majority of that coming from fossil fuels. According to the IEA, 36% of its total supply is met by oil alone.

Some 95% of Japan’s oil comes from the Middle East, with about 70% travelling via the Strait of Hormuz – a crucial shipping route currently under effective blockade, reported Reuters.

That means approximately two-thirds of Japan’s oil supply could currently be prevented from reaching its destination.

‘80 million barrels’

On Wednesday, as the International Energy Agency called for an emergency release of global oil reserves, Japanese prime minister Sanae Takaichi announced she would “release” 45 days of stockpiled oil, the largest volume in Japan’s history, according to the Asahi Shimbun.

This is only a portion of the 254 days of oil Japan has stockpiled, but if a supply shortage were to become severe, the prime minister may have to consider “restriction of energy usage”, like that seen during the oil shocks of the 1970s, Ichiro Kutani, director of the energy security unit at the Institute of Energy Economics, told Carbon Brief.

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) launched an oil embargo against countries suspected of supporting Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur war, including Japan.

The subsequent shock for Japan’s economy was a major factor in the country’s shift from heavy industries to lighter industries such as electronics, academics have said.

Kutani told Carbon Brief:

“The failure to achieve the goal of reducing dependence on the Middle East for crude oil – pursued for more than 50 years since the 1970s oil crisis – is a bitter lesson.”

‘Nuclear’

On Monday, an opposition leader called on Takaichi to reopen Japan’s remaining fleet of nuclear power plants “as a carbon-free power source with less dependence on overseas sources”.

Prior to the Fukushima disaster in 2011, nuclear power provided roughly 30% of Japan’s electricity.

All 54 of Japan’s nuclear power plants were taken offline in 2011 after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant meltdowns.

Over the past decade these have been slowly coming back online, but 18 out of 33 operable plants remain closed.

Takaichi has previously been vocal in her support of restarting Japan’s fleet of nuclear power plants, but developments in Iran “may add urgency to the debate”, Yuko Nakano of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told Carbon Brief.

Takeo Kikkawa, president of the International University of Japan, told S&P Global that the expansion of renewables has played a role in making up the shortfall from less nuclear power, adding:

“Now, with nuclear reduced to about 8%, renewables, especially solar, have increased to make up some of the difference. But overall, the combined self-sufficiency rate is still only about 15%.”

‘US-Japan summit’

Takaichi has so far resisted condemning or endorsing the attacks on Iran and refrained from making an assessment on the legality of US-Israeli strikes.

This could change next week, however, when she meets president Donald Trump for a US-Japan summit arranged before the war broke out.

In Washington DC, she may be expected to provide a more “full-throated endorsement” of the US war effort, “if not an outright request for Japan to dispatch its forces in support of US military activities in the Persian Gulf,” Tobias Harris, founder of Japan Foresight, a Japan-focused advisory firm in the US, said in a statement.

The Japanese government was already increasing oil imports from the US to diversify after the supply shocks from the Russia-Ukraine war – a trend that will likely be “further encouraged” by the Middle East war, said Dr Jennifer Sklarew, assistant professor of energy and sustainability at George Mason University. She told Carbon Brief:

“The overall effect of the war in the Middle East, thus, may be greater Japanese dependence on US oil and gas.”

Watch, read, listen

PLEDGE WATCH: The Cypress Climate Advisory group released a “NDC benchmarker” that monitors countries’ emissions against their nationally determined contributions (NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

FEMALE LEADERSHIP: A comment piece in Climate Home News explored why women’s leadership is “central” to unlocking the global phaseout of fossil fuels.

NOW OR NEVER: Martin Wolf, the chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, argued that one of the economic lessons from the Iran war is the “need to invest in renewables, in order to reduce vulnerability”.

Coming up

- 9-19 March: 31st Annual Session of the International Seabed Authority, Kingston, Jamaica

- 15 March: Republic of the Congo presidential election

- 15 March: Vietnam parliamentary election

Pick of the jobs

- Grantham Institute for Climate Change, assistant professor or associate professor | Salary: £70,718-£80,148 or £82,969. Location: London

- Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), China analyst | Salary: Unknown. Location: Remote/London

- Climate Action Network, campaign officer | Salary: £31,069-£33,140. Location: Flexible

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to [email protected].

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.