Factcheck: Why expensive gas – not net-zero – is keeping UK electricity prices so high

Multiple Authors

05.20.25Multiple Authors

20.05.2025 | 8:00amThe UK’s high electricity prices have become intensely political, with competing claims over the cause of rocketing bills and how best to get them down.

Prices spiked after Russia cut off gas exports to Europe, precipitating a global energy crisis alongside its invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The UK has been particularly exposed, as gas sets its wholesale power prices 98% of the time – and gas remains three times more expensive than before the crisis.

Nevertheless, some have sought instead to misleadingly blame the UK’s high power electricity on “green levies” that support the expansion of clean power, as well as the target for net-zero emissions by 2050.

While the UK is making significant investments in new clean-power capacity and in upgrading its electricity grid, “green levies” and network charges account for just 6% and 20% of the rise in bills since before the energy crisis, respectively, against 53% due to wholesale prices driven by gas.

Moreover, part of the rise in network charges is also down to gas, resulting from utility firms going out of business during the energy crisis, as well as high gas-related costs for managing the electricity grid.

Dhara Vyas, chief executive of industry body Energy UK tells Carbon Brief that it is “crystal clear what has driven electricity bills up in the UK…it’s the wholesale costs, driven by the price of gas”.

This article looks at how electricity prices could be reduced in the short- to medium term and why the transition to clean power is, ultimately, expected to result in lower energy bills overall.

(This article refers to the UK throughout, but strictly relates to the island of Great Britain made up of England, Scotland and Wales. Northern Ireland is part of the separate all-Ireland electricity system.)

- Why are UK electricity prices so high?

- What has driven the rise in UK household electricity bills?

- Why network charges on electricity bills are going up

- What about UK industrial electricity prices?

- How could UK electricity prices be cut?

- What will the UK’s climate goals mean for bills in the future?

Why are UK electricity prices so high?

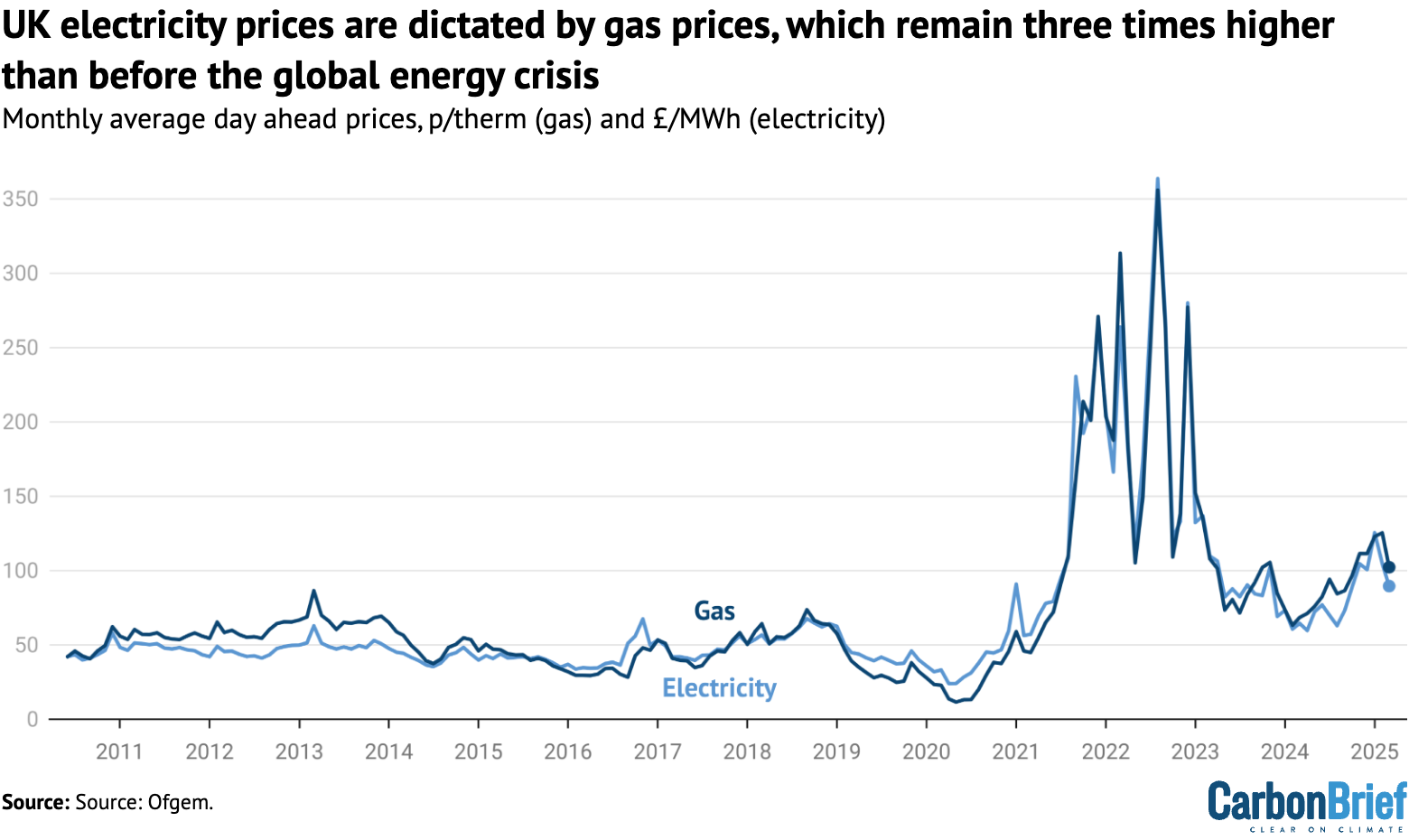

In the months before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, global gas prices had already started to rise as the global economy bounced back from the Covid pandemic and Russian president Vladimir Putin began restricting energy supplies to Europe.

In the wake of its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia then cut off the bulk of gas deliveries to Europe, having previously been the continent’s biggest source of the fuel.

Gas prices rocketed – and so did the UK’s energy bills. Millions of households were left in fuel poverty, despite the government spending £100bn on support to alleviate the pressure.

While gas prices have subsided from their historic highs in 2022, as of May 2025, they remain three times higher than they were before the global energy crisis.

As such, despite all of the media commentary and politicians’ speeches arguing the contrary, the UK’s exposure to high gas prices is still, by far, the biggest reason for the country’s high electricity prices.

(In 2022, International Energy Agency (IEA) chief Dr Fatih Birol wrote in the Financial Times that it was “absurd” to blame high prices on clean energy. He added: “When people misleadingly blame clean energy and climate policies for today’s energy crisis they are, intentionally or not, moving the spotlight away from the real culprits – the gas supply crunch and Russia.”)

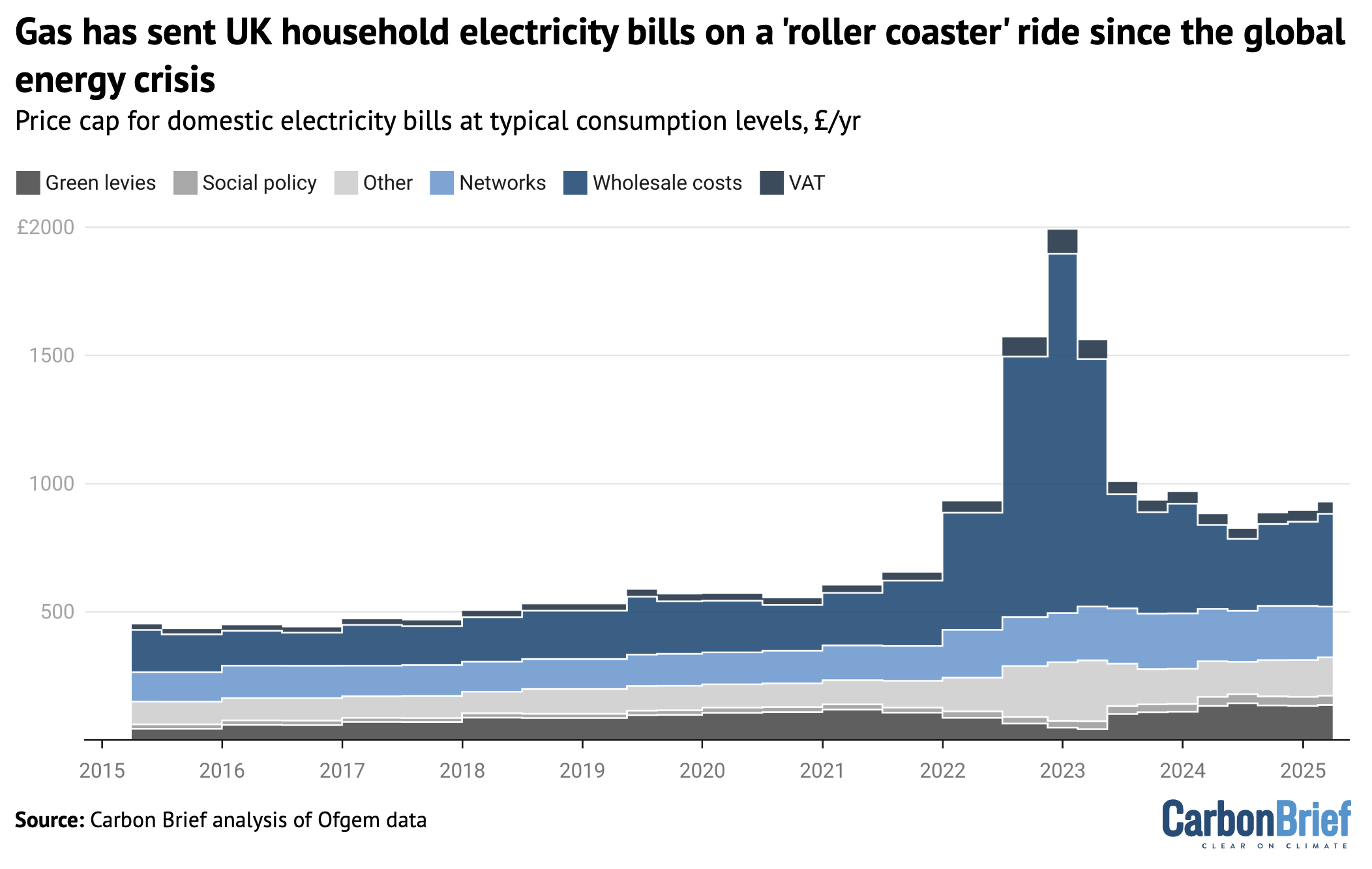

The figure below shows the price cap for household electricity bills set by energy regulator Ofgem, breaking down the different elements of average household costs over the past decade.

The biggest driver of recent increases in electricity bills is the wholesale price of electricity, which is set in the UK almost exclusively by wholesale gas prices (see below).

Consequently, the spike in electricity bills shown by the dark blue area in the figure below is a reflection of the spike in gas prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

In contrast, “green levies” – costs added to bills in order to pay for government climate policies – actually fell during the height of the gas price spike, as the dark grey area of the chart shows. They are currently only marginally above pre-crisis levels.

In recognition of these basic facts, the UK’s prime minister Keir Starmer has reiterated the link between high energy bills and the country’s exposure to fossil-fuel prices.

The UK’s households and businesses have “paid the price” for “our over-exposure” to fossil fuels, he told an energy security summit in London at the end of April 2025, attended by Carbon Brief and jointly hosted by the UK government and the IEA.

Starmer told the summit that half the UK’s recessions since the 1970s had been caused by “fossil-fuel shocks” and that his government was “determined” to get the country off the “roller-coaster of international fossil-fuel markets” by shifting to clean energy:

“When it comes to energy, we’re also paying the price for our over-exposure, over many years, to the roller-coaster of international fossil-fuel markets, leaving the economy and therefore peoples’ household budgets vulnerable to the whims of dictators like [Russian president Vladimir] Putin, to price hikes, and to volatility that is beyond our control.”

Under the latest price cap from Ofgem, the average household now faces an electricity bill of £926 per year, up from £603 before the energy crisis – a rise of 54%.

Two-fifths of the current cap is made up of wholesale costs (38%), one-fifth from network charges (22%), plus another one-fifth from green levies (15%) and social policies (4%). The final fifth of the bill is made up of operating costs (14%), profits (2%) and other items.

The biggest change in these costs has come from the spike in wholesale energy costs.

Other elements of household electricity bills have also gone up over the past decade, including network charges and levies. (See: What has driven the rise in UK household electricity bills?)

However, the gradual rises in these other costs have been overwhelmed in recent years by the huge spike in wholesale power prices driven by expensive gas.

One common objection to these facts is that gas prices have been equally eye-watering in other European countries, but their electricity prices have not been quite so affected as the UK’s.

Whereas the UK once had middling power prices relative to other European countries, it has risen up the ranks to post some of the continent’s costliest electricity per unit.

(Figures comparing electricity prices in European capital cities in April 2025 put the UK fourth, whereas France is close to the continental average.)

The biggest reason for this rise in the UK’s relative prices is the fact that its power system is far more exposed to gas-fired generation than other countries.

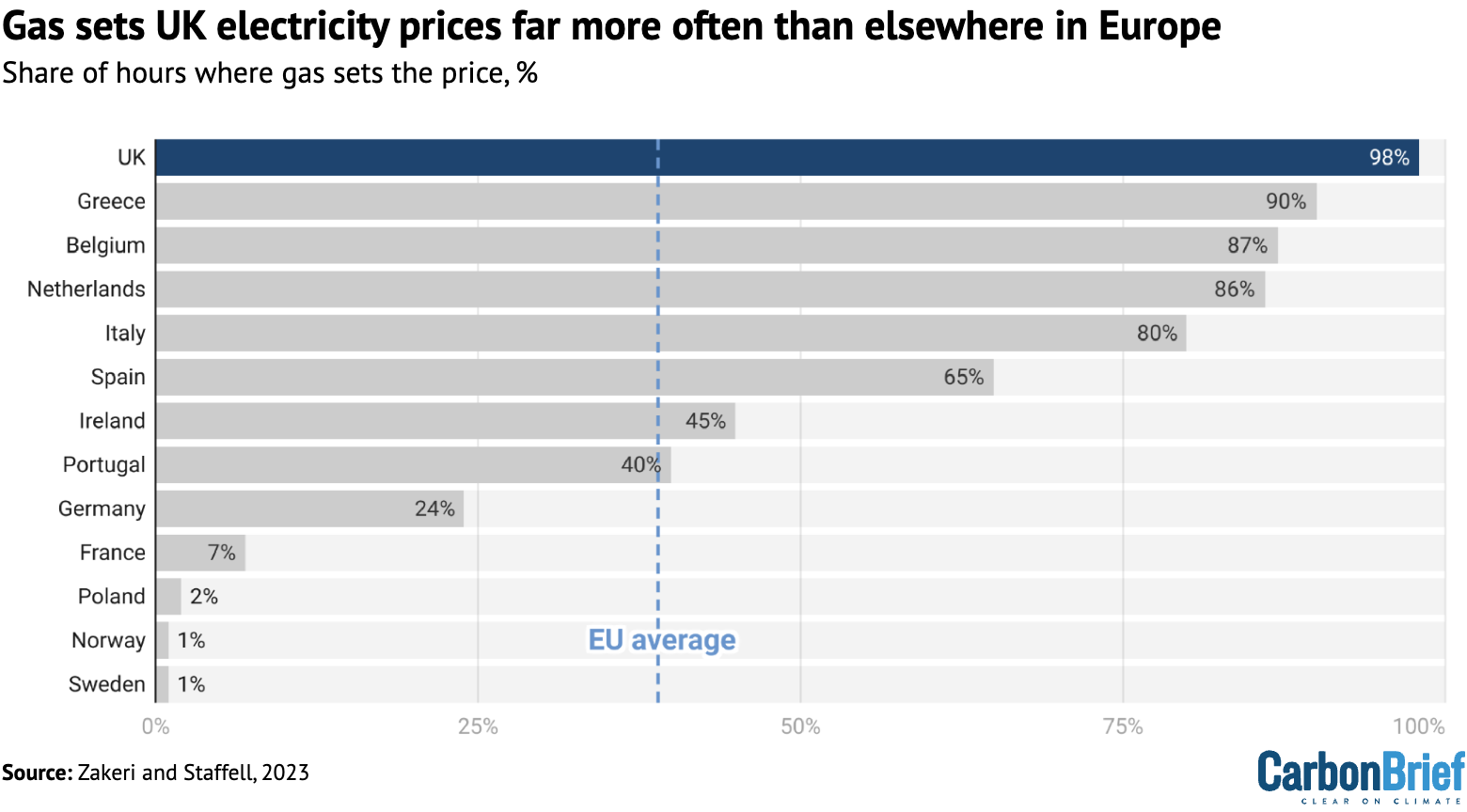

Specifically, gas sets the wholesale price of electricity in the UK 98% of the time, according to academic research published in 2023. This is far more often than in other European countries, including France (7%) or Germany (24%), as shown in the figure below.

The UK’s electricity market operates using a system known as “marginal pricing”. This means that all of the power plants running in each half-hour period are paid the same price, set by the final generator that has to switch on to meet demand, which is known as the “marginal” unit.

While this is unfamiliar to many people, marginal pricing is far from unique to the UK’s electricity market. It is used in most electricity markets in Europe and around the world, as well as being widely used in commodity markets in general.

Still, the UK’s current electricity mix means that gas is almost always the marginal fuel, even though it only accounts for a third of generation overall.

(In contrast, the marginal fuel in many other European countries is hydro. In France, it tends to be nuclear, while in Germany it is split between coal, gas and hydro.)

The result is that the UK’s wholesale electricity prices track wholesale gas prices almost perfectly, as shown in the figure below.

In summary, the UK electricity system is far more heavily exposed to gas prices than those of other European countries and, consequently, its power prices have been hit harder by the energy crisis.

Prof Rob Gross, director of the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC), tells Carbon Brief:

“I think the bottom line on it all is that we are particularly exposed to gas prices…That’s the principal driver of our [electricity] prices.”

Energy UK chief Vyas said in a recent statement that “it’s the volatile cost of fossil fuels and our dependence on them that have driven up energy bills for customers”.

In comments to Carbon Brief for this article, Vyas expands on the point, explaining how the UK’s exposure to imported fossil fuels has left it worse off than its neighbours:

“Our electricity prices are high largely because our energy system depends on imported gas – and because of the extent to which that gas sets the price for electricity. This is what has driven UK bills to record levels in recent years – and why, despite falling from that peak, they remain high compared to three years ago. It’s also largely why our energy costs are higher than our European counterparts.”

What has driven the rise in UK household electricity bills?

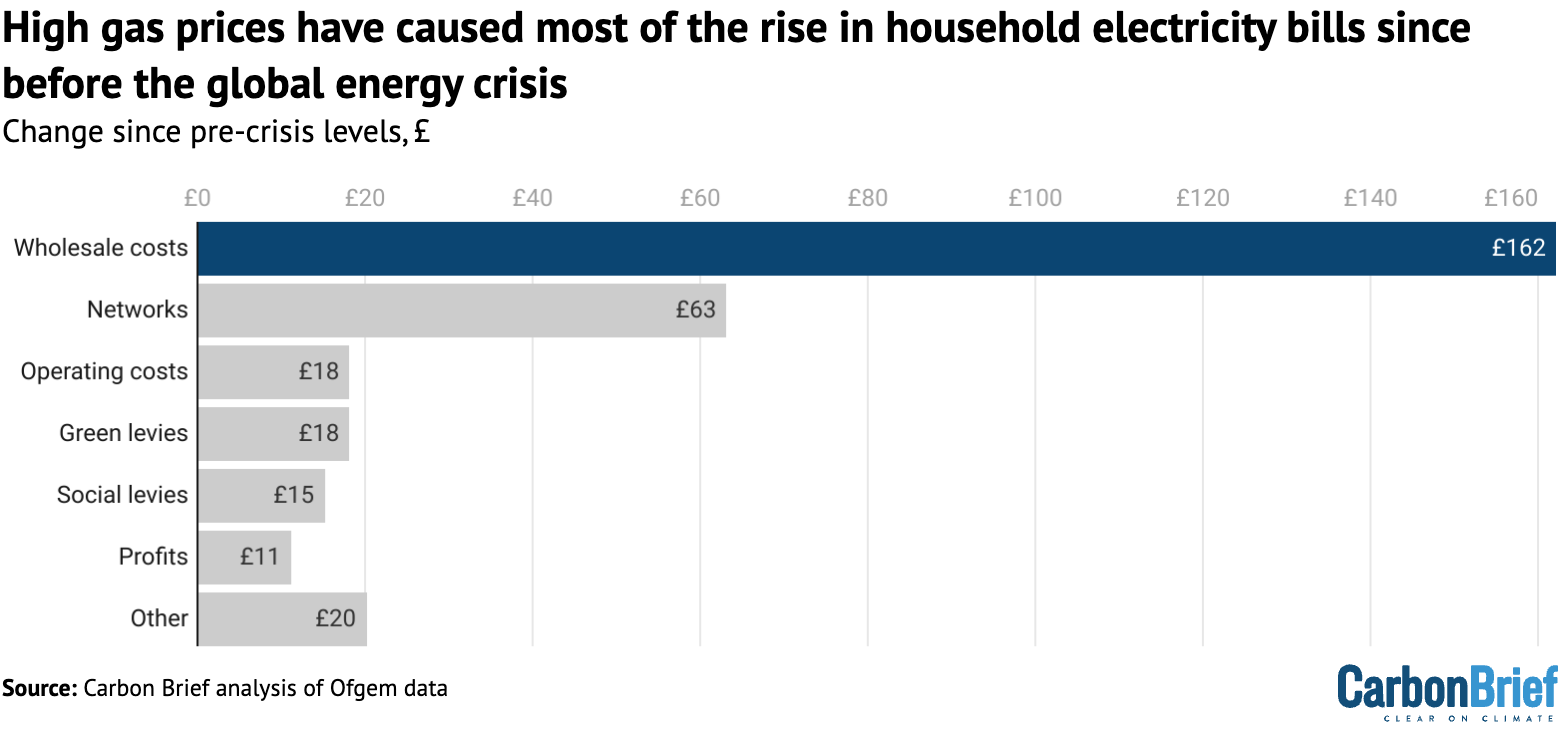

Since 2021, the household electricity price cap set by regulator Ofgem has risen from £603 per year for average households to £926 per year – an increase of £324, or 54%.

Some £162 of the increase is due to wholesale costs, which have roughly doubled over the period.

Put another way, the UK has spent £140bn on buying gas since the start of the global energy crisis, according to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU).

Vyas tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s crystal clear what has driven bills up in the UK. If you look at any data about our energy bills over the last 5 years – every single time it’s the wholesale costs, driven by the price of gas, that pushes bills up or down. The policy costs on bills (sometimes referred to as green levies) hardly shift.”

Underneath the large spike in wholesale power costs due to the “roller coaster” of international gas markets, there have also been steady increases in policy and network charges in recent years. This includes the “green levies” that support the expansion of the UK’s clean energy supplies.

Specifically, some £63 has been added to bills since 2021 as a result of rising network charges, another £18 from “green levies” and £65 from other sources.

(Notably, as explained below, part of the rise in network charges is also due to high gas prices.)

This means that network charges and “green levies” account for 20% and 6% of the rise since pre-crisis levels, respectively, compared with 54% due to higher wholesale prices.

These contributions to the increase in electricity bills since 2021 are shown in the figure below.

As explained above, the driver of higher wholesale electricity costs is high gas prices, with the fuel remaining three times more expensive than before the global energy crisis.

In contrast, “green levies” have gone from £118 per year in summer 2021 to £137 today. As bills rose dramatically in this period, the share due to green levies has dropped from 20% to just 15%.

The small rise in green levies is due to a £22 inflationary increase in the cost of the “renewables obligation” (RO) scheme, which closed to new projects in 2017. The RO currently adds £89 per year to average household electricity bills, some 10% of the total.

Ironically, this means that the cost of renewable support has risen, at least in part, because of high gas prices, which have contributed to higher-than-expected inflationary pressures.

The RO still supports around 30% of UK electricity supplies, but the first tranche of 15-year contracts will come to an end from 2027, meaning the cost will fall over time.

In 2023, the then-Conservative government sought views on changing the measure of inflation used to calculate the RO each year from the “technically deficient” index known as “RPI”, to the lower “CPI”. However, this shift was not pursued.

The cost of renewables that hold newer “contracts for difference” (CfDs) has actually fallen by £5 per household per year since before the energy crisis – from £32 to £27 – despite supporting more capacity than four years ago.

This is because CfDs offer a fixed price for each unit of electricity generated. As wholesale prices have climbed, the top-up needed to meet this fixed price has fallen. CfDs currently account for less than 3% of average electricity bills, down from 5% before the crisis.

In total, the RO and CfDs currently add around £10bn a year to end-user electricity bills, of which households account for around a third. This amounts to £116 per household per year.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that the combined cost of the RO and CfDs will rise by 3% between now and the end of the decade, from £9.6bn to £9.9bn.

Current electricity bills also include £20 to pay for “feed-in tariffs” (FiTs), which were offered to small-scale renewable schemes until 2019. This is up by £2 per year since before the crisis.

FiTs also rise with inflation, but, as with the RO, the scheme is closed to new projects. This means costs will fall over time as the oldest installations see their contracts coming to an end.

The cost of government social policies adds another £36 to average electricity bills, up £18 since summer 2021 due to higher spending on insulating the homes of families on low incomes.

This type of spending had been falling until 2019, after the then-Conservative government tried to lower energy bills from 2013 by “cutting the green crap”. Although these efforts reduced bills in the short term, they ended up adding £22bn to bills in the long term, previous Carbon Brief analysis found, because they left homes more exposed to the spike in gas prices during the energy crisis.

Vyas tells Carbon Brief:

“For well over a decade, investors have been telling us they want to see ambition and certainty from government. Taking a ‘boom and bust’ approach, where policy and direction of travel keep changing, adds costs to everyone’s bills. For example, the infamous move to ‘cut the green crap’ cost customers in this country billions of pounds, as Carbon Brief has demonstrated.”

Why network charges on electricity bills are going up

Alongside wholesale prices, network charges have also seen significant increases since before the global energy crisis, as noted above. These charges have risen by £63 from £136 a year in summer 2021 to £198 today, up by nearly 50%.

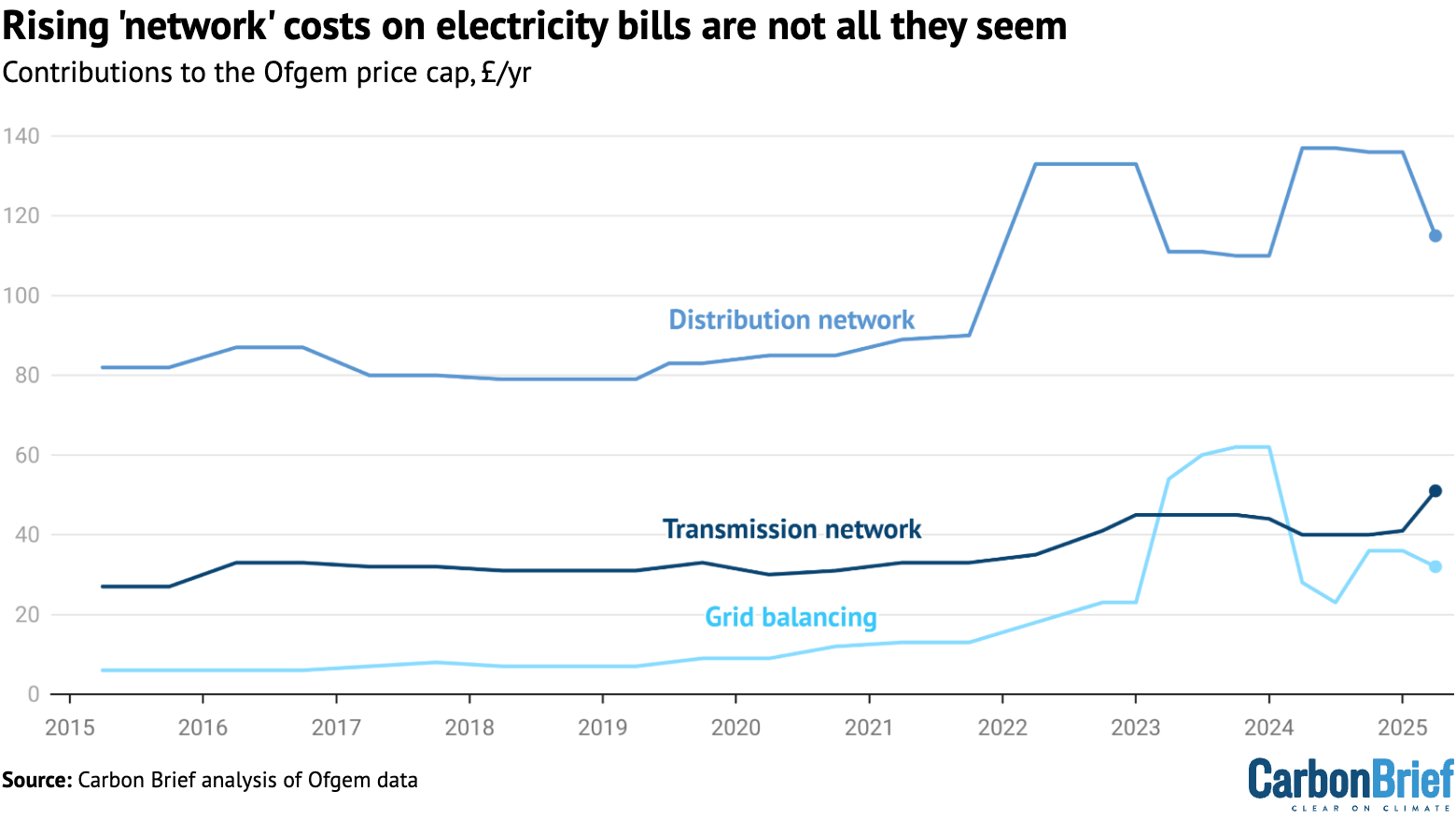

The figure below breaks down the £200 cost of network charges per household per year.

Some £115 of this – 13% of bills – is earmarked for “distribution” networks, which deliver electricity to households and businesses at lower voltages. This segment has seen the largest increase of all network charges, adding £25 per year.

Next is the national “transmission” network, at £51, which moves electricity around the country on towering pylons carrying high-voltage lines – sometimes referred to as the “motorways of the grid”. While these costs have risen by more than half since 2021, this still only added an extra £18 to bills each year.

The third component is grid balancing, which reflects the costs of making sure that supply and demand are perfectly matched at all times. This has soared from £12 a year in 2021 to £32 today.

Many articles on the UK’s high electricity bills have said that rising network charges are due to the cost of managing and expanding the grid to cope with new, variable wind and solar generation.

While major investments are being made in the grid, the rise in network charges is not all it seems. Indeed, parts of these increases are also due to high gas prices.

For example, the cost of bailing out the dozens of electricity retailers that went out of business during the energy crisis – ultimately, as a result of high gas prices – is being paid for by households and is included within distribution network charges under the Ofgem price cap.

The amounts being added to bills to pay for these bailouts, within each of the price-cap periods shown in the figure above, is not routinely disclosed by Ofgem.

However, in 2022, Ofgem said that £66 was being added to household bills to pay for these failures under a scheme known as the “supplier of last resort” (SoLR). This aligns with the first hump in the figure above – and the second hump likely relates to further SoLR costs.

For grid balancing costs, there is a similar story, because high gas prices make it more expensive to manage the electricity system.

National Grid Electricity System Operator (NESO) sometimes pays gas power plants to switch on – and these “redispatch” instructions are more expensive as a result of high gas prices.

NESO explains that balancing costs are “strongly in correlation to the wholesale spot electricity markets and [therefore] dependent on the natural gas market”.

A gas-related bump in balancing costs is clearly evident in the figure above.

There have been two other important drivers of rising balancing costs. First, an increase in the number of balancing actions that NESO needs to take, mainly relating to “constraints” on the network that result in wind projects being paid to switch off – known as curtailment.

Constraint costs have risen because grid capacity has not kept pace with the number of new wind power projects being built, particularly in Scotland.

A series of new grid connections are being built between Scotland and England, which will add to transmission charges while cutting balancing costs.

The second additional factor for balancing charges is that, since 2023, consumers have paid for 100% of these costs, whereas they were previously shared equally with electricity generators.

Despite their rapid recent rise, balancing charges still only add £32 a year to average household electricity bills, including the much–publicised cost of wind constraint payments.

One analyst tells Carbon Brief:

“I know people make a great fuss about constraint payments…it sounds like a big number. It’s actually not, in terms of its impact on bills.”

A final important factor in rising network charges is that the UK’s electricity networks are ageing and require significant ongoing investment in order to replace old equipment before it fails.

(For example, the substation fire that closed Heathrow airport earlier this year started in a transformer that had been commissioned in 1968, making it 57 years old.)

Moreover, grid operators have been allowed to increase their investments in recent years, partly in order to make up for previous periods of what a select committee report called “under-investment”.

The 2003 report, on the resilience of the electricity network, said that customers at the time had been “living off the investment made by [their] predecessors” and that there was “insufficient investment” to replace old equipment “in a planned and orderly way”.

Similarly, a 2009 Ofgem report on energy network price controls found that distribution network operators “may not have been carrying out the investment required to maintain” the grid.

Gross tells Carbon Brief:

“My suspicion is that the investment to facilitate renewables being connected to the grid is a pretty small fraction of that increase [in network charges]…I think [a lot of it is] the legacy of maybe…squeezing and minimising expenditures in the immediate post-privatisation period.”

To be clear, it remains the case that major investments are being made in expanding the grid – and that these investments will, ultimately, be paid for via consumer electricity bills.

Yet, to take one example, expanding the distribution network to support the electrification of heat and transport will add just £5-10 to annual household bills by 2030 and £20-25 by 2050, according to a February 2025 report from the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC), now part of the National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority.

The relatively low annual cost increase to households is despite these investments totalling as much as £50bn, according to NIC. (This is a good illustration of the way that “scary-sounding numbers” can be used to mislead people about the “cost” of the transition to net-zero.)

Moreover, NIC expects household energy bills to drop significantly overall by 2035, even as electricity network charges rise. (It sees the average dual-fuel bill for electricity and gas falling from just shy of £2,000 a year in 2019 to around £1,300 by 2035 and to less than £1,200 by 2050.)

In broader terms, rising levies and network charges illustrate the changing nature of electricity bills – and energy bills more broadly – as the UK shifts towards net-zero.

Historically, fuel costs have accounted for the bulk of energy bills, including not only household gas and electricity, but also the cost of motoring.

In a net-zero future, fuel costs would be massively reduced, as gas for heat and power, as well as petrol in cars, are progressively replaced with more efficient electrified alternatives.

Notably, this means that part of the cost of upgrading, decarbonising and expanding the UK’s electricity system would translate into major savings in the cost of UK transport.

This transition carries upfront capital costs to build new clean power sources, as well as the infrastructure needed to connect them to consumers and to manage their variable output.

However, the cost of these upfront investments will be spread over many years. Moreover, they are ultimately expected to pay dividends via lower operating costs (See: What will the UK’s climate goals mean for bills in the future?)

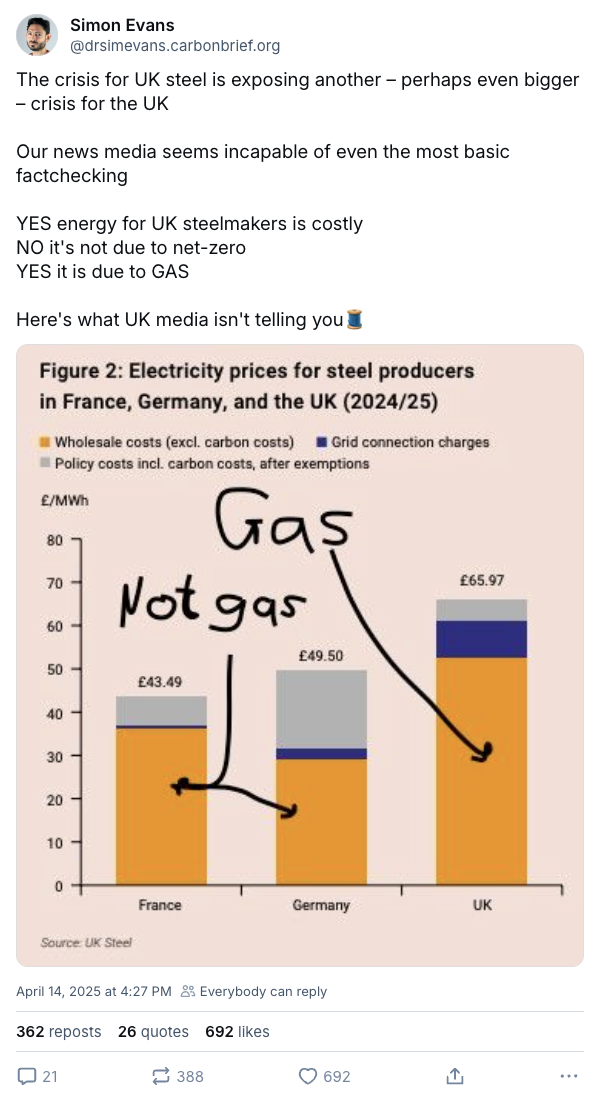

What about UK industrial electricity prices?

The UK’s industrial electricity prices have also been a prominent fixture in the debate over why energy costs have become so high, particularly following the latest crisis in steelmaking.

In November 2024, the Financial Times had published a chart showing that industrial electricity prices in the UK in 2023 were far higher than in any other country listed.

The idea that the UK’s industrial power prices are among the “highest in the world” has now become firmly embedded in the political discourse.

Yet this discourse frequently ignores the dominant role of gas in driving high prices.

In her March 2025 speech abandoning Conservative support for the UK’s net-zero by 2050 target, opposition leader Kemi Badenoch misleadingly blamed high power prices on climate policies in general and “environmental levies” in particular.

The debate around industrial power prices was supercharged at the end of March with the news that the owner of the Scunthorpe steelworks, British Steel, planned to shut it down.

After the closure was averted by a government takeover, an April editorial in the Daily Telegraph illustrated the tenor of much of the commentary in right-leaning, climate-sceptic newspapers by confidently blaming the crisis on “sky-high energy costs imposed by successive governments in the name of net-zero”.

Like so many others debating the UK’s high industrial electricity prices, the editorial failed to even mention the word “gas”, let alone acknowledge its role in driving up costs.

In reality, the UK steel industry is completely exempt from “environmental levies” and – under the government’s “supercharger” scheme – it also gets relief from the majority of network costs.

While the UK steel industry still faces higher electricity prices than its counterparts in the likes of France or Germany, this is almost entirely down to expensive gas driving up UK wholesale prices.

Indeed, as UK Steel explained in a recent report, environmental levies have a smaller impact on steel industry electricity bills in the UK than in neighbouring countries.

Frank Aaskov, director, energy and climate change policy at UK Steel, tells Carbon Brief that the debate around industrial energy costs since the start of the global energy crisis has been “poorly informed”, adding that that is “probably a bit of an understatement”.

Some actors have been “willingly misinforming others” by blaming net-zero for the problems in the steel industry, says Aaskov, adding that other factors are “much more important”. He says:

“Net-zero, in itself, is not the cause of the decline in the steel industry. There are much more important factors, such as global overcapacity, [as well as] inflexible and unambitious trade policies.”

While Aaskov identifies high industrial electricity prices as a “key factor” for the sector, he says that “today, it’s not net-zero policies” that are causing those prices to be high. He says:

“Today, [net-zero policies] are not the driver of high industrial electricity prices in the UK. It is higher network charges – because we have lower exemptions than there are in Germany and France – and it’s the cost of natural gas, which is driving the higher wholesale price.”

Aaskov says attempts to blame net-zero are “unhelpful to the steel industry, especially because we as a sector have committed to decarbonising, our members are making huge investments in reducing emissions and Port Talbot is the key example of that”.

How could UK electricity prices be cut?

Ever since the start of the global energy crisis in 2022, debate has been raging over how to get spiralling energy bills under control.

The spike in gas prices put the spotlight on its role in setting wholesale power prices via marginal pricing, leading some people to call for electricity market reform.

In April 2022, the then-Conservative government launched a “review of electricity market arrangements”, known by its acronym REMA. It ran the first consultation in July that year.

Although the review was much broader in scope, it was presented as a way to tackle high electricity prices and – potentially – to decouple them from the high price of gas.

In the foreword of the first REMA consultation, then-energy secretary Kwasi Kwarteng said that the electricity markets will be the “backbone” of the future electricity system, so it is “critical” to get the design right. He added:

“The last major programme of electricity market reform was 10 years ago and left some key parts of our market structure unchanged from the time when fossil fuels were the dominant source of energy; it is time to look again at whether they are fit for purpose, or whether reform is needed to deliver a clean, secure and low-cost energy system for consumers.”

The consultation explained that, while the use of marginal pricing left UK wholesale power prices “closely track[ing] gas prices”, the impact of this would “naturally diminish over time” as the share of generation coming from gas declined and that of clean power increased.

Still, it set out a number of options for explicitly breaking the link between wholesale power prices and the price of gas, such as a market that was “split by characteristic”, or that offered generators a price reflecting their own costs, rather than that of the marginal unit (“pay-as-bid”).

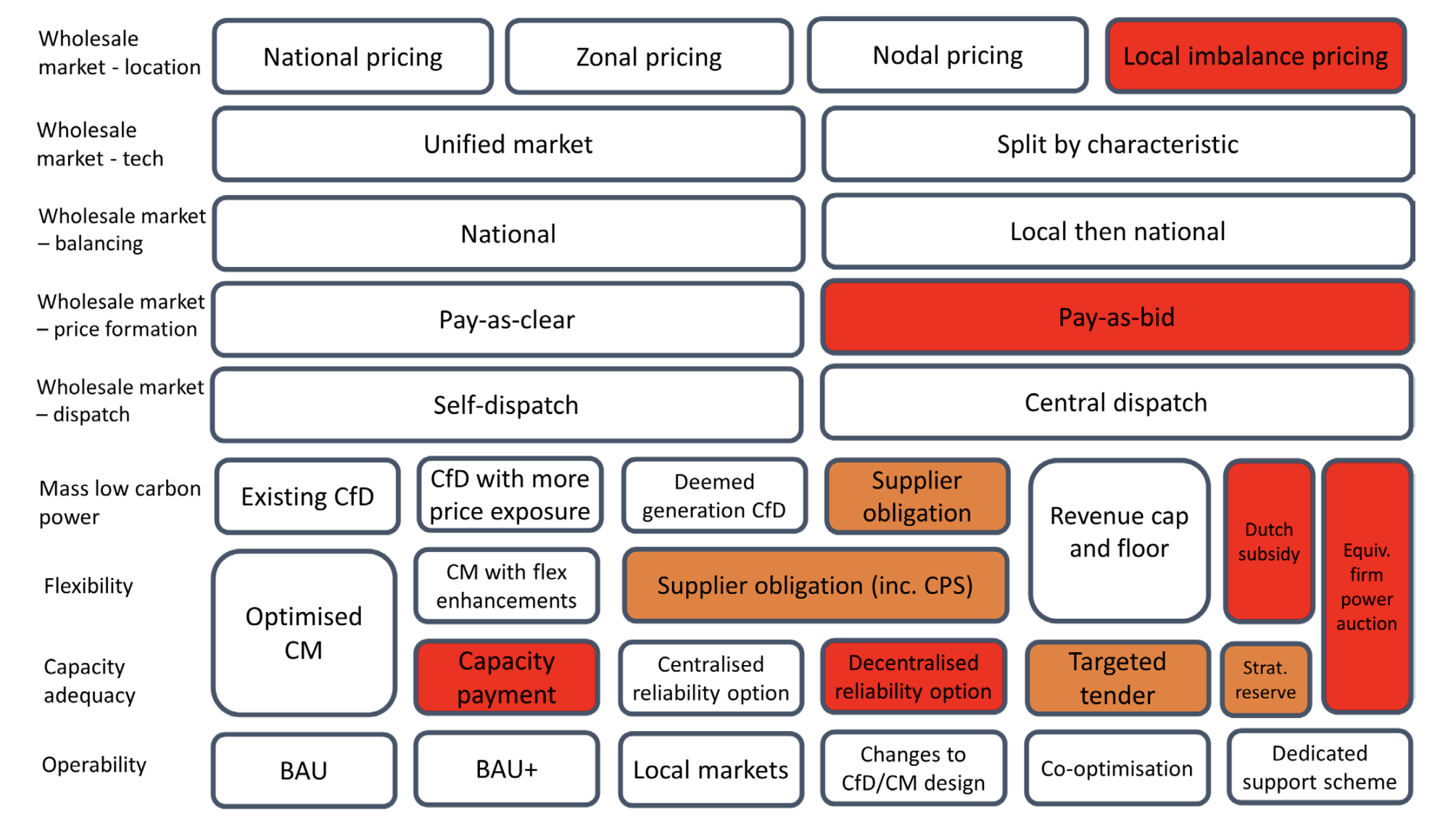

A summary of the responses to this consultation was published in March 2023, with the government deciding to rule out a number of options – including “pay-as-bid” – shown in the figure below.

Source: Review of Electricity Market Arrangements: summary of responses to consultation, March 2023.

A second consultation followed in March 2024, with the results published alongside the REMA autumn update in December 2024.

This narrowed the options still further, including ruling out both the “green power pool” and split market options, both of which would have created a separate market for renewables.

This means that, while there are numerous options within REMA that are still being considered, breaking the link between wholesale power prices and the price of gas is no longer on the table.

The core final decision within REMA is now between reforming the current national wholesale market, where this is a single price for wholesale electricity across the country, or switching to a regional market split into a number of zones with their own prices.

Both options would continue to use marginal pricing, whether at national or regional level. The switch to “zonal” pricing has been made in numerous markets in recent years, including Ontario, Italy, Denmark and Australia. It is also being considered in Germany.

In the UK, the “bruising” question around whether to adopt zonal prices is seen as the “most hotly contested aspect” of REMA and has become an “energy death-match”.

As such, despite the role of gas in wholesale power prices continuing to be the biggest driver of high electricity bills, it has come to dominate the discussion around market reform.

Those who support zonal prices have claimed it would more closely reflect local supply and demand conditions, ultimately leading to a more efficient electricity system, as well as helping to cut network costs.

Analysis by the Energy Systems Catapult suggests that it would save £30bn by 2035, while a study by FTI Consulting for Octopus Energy found that it could save consumers between £55bn and £74bn by 2050.

Octopus Energy and its CEO, Greg Jackson, are some of the most vocal proponents of zonal pricing. Jackson and supporters argue that while it is true that wholesale prices and CfD payments would increase under a zonal system – by £35bn and £15bn, respectively, over 25 years – these would be more than offset by a drop in constraint costs and “congestion rents” of £40bn and £65bn.

The impact on constraint costs is a core pillar of the argument for zonal. However, grid balancing costs overall – including constraints – currently only make up 4% of electricity bills. (See: Why are UK electricity prices so high?)

The shift to zonal pricing is also supported by key organisations such as Ofgem, NESO and Citizens Advice.

However, there is also a long list of groups that are strongly opposed to zonal pricing, including Energy UK, Renewable UK, energy intensive industries and many individual energy firms.

These organisations have mustered numerous studies of their own, which they say show that zonal pricing could dent investment and could, as a result, even raise costs for consumers.

In the public realm, the main criticisms of zonal prices focus on the potential for it to create a “postcode lottery” for consumers and to create uncertainty – and higher costs – for investors in the clean power capacity needed to hit UK targets.

For example, a report prepared by consultants LCP Delta for energy company SSE found that zonal pricing could increase wholesale prices across 97% of the country. Its research suggested a drop in wholesale costs would only be seen in Northern Scotland.

(Advocates for zonal argue that these higher wholesale costs would be outweighed by lower costs for building and managing the electricity network.)

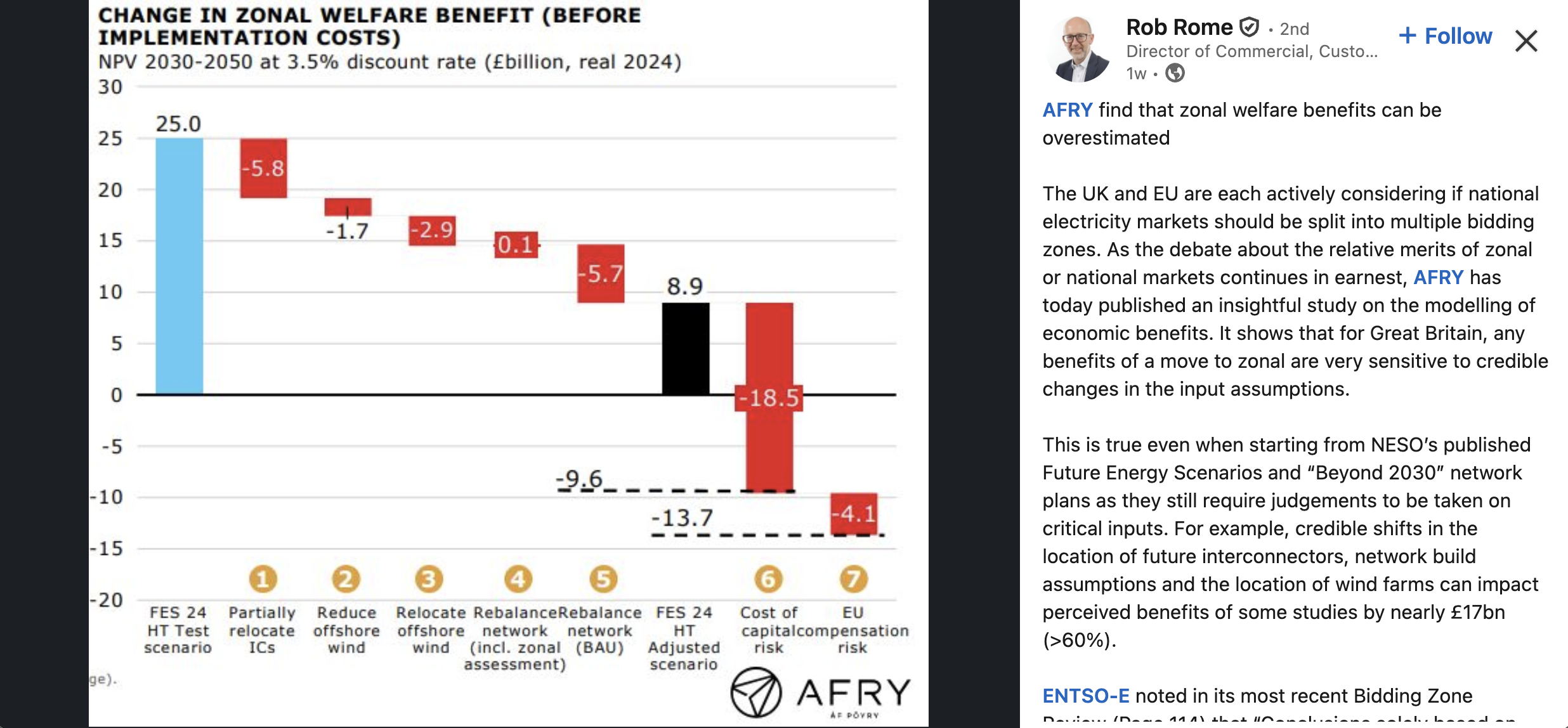

Recent research by consultancy Afry, summarised in the screenshot below, suggests that the savings from a shift to zonal pricing are “overestimated” and that risks, such as higher borrowing costs, could mean it translated into an increase in energy bills overall.

Jane Cooper, deputy CEO at trade body RenewableUK, said in a statement that people in England and Wales are “rightly worried” about zonal pricing creating a postcode lottery, adding:

“This scheme would create so much uncertainty in our electricity market that it could disrupt investment in vital new clean-energy projects and push up their costs, at the very time when we need to start building at pace to deliver the government’s target of clean power by 2030. We’re urging ministers to rule out zonal pricing as soon as possible and to focus on policy decisions which do not undermine the confidence of investors.”

(Analysis by Cornwall Insight highlights that there is already a “postcode lottery” of sorts, with households in London paying £120 less than those in north Wales and Merseyside over the coming year. This is to do with the variation in the regional distribution network charges added to bills. The figures in the sections above are national averages.)

Modelling from UKERC found that zonal pricing could increase strike prices in the next CfD auction by up to £20 per megawatt hour (MWh), as investors seek to factor in the associated risk. It found that higher prices in the CfD auctions could increase consumer costs by £3bn a year.

Non-profit Regen highlighted that the £55bn savings over 20 years, as suggested by FTI, only equates to around £31 per household per year, if applied evenly across current demand.

Ultimately, the debate around the benefits of zonal prices continues, with many aspects of the exact design of such a system – for example, how many zones there would be – still undecided.

The government is expected to make a decision on whether to switch to zonal power pricing ahead of the seventh CfD allocation round in summer 2025, to minimise the impact on renewable energy investment by providing greater certainty.

Zonal was chosen over nodal in part because it would be simpler to implement, with the government estimating in 2023 that this would take about 18 months. (It is not clear if this 18-month timeline includes consultation, such as on the number of zones.)

Subsequently, the government has told industry that a shift to zonal pricing would not be put in place until 2032, according to RenewableUK.

This is supported by recent analysis from consultants Cornwall Insight, which suggests that a shift to zonal would take closer to five years, until the mid-2030s.

In a statement, Kate Mulvany, principal consultant at Cornwall Insight, said:

“The government’s commitment to a decision by mid-2025 is welcome. But we must be realistic: this is the start of a long road, not the finish line. Clear, early communication and a credible delivery timeline will be essential to retain market confidence, keep renewables investment and avoid unintended consequences, which could have substantial impacts on government targets.

“Zonal pricing may still form part of the long-term vision for electricity market reform. But, for now, its delivery sits firmly in the next decade.”

With zonal pricing – and any associated changes in the costs of the electricity system – unlikely to kick in before the next election in 2029, the hunt for options to cut bills more quickly continues.

However, there are currently no mechanisms in place that would guarantee a reduction in energy bills in the short term, according to Energy UK, meaning potential reductions would only be possible if the gas wholesale market tumbles.

Gross says: “We could all cross our fingers and hope that the global price of gas will collapse over the next few years…[But] it’s definitely not a great energy-security strategy for the long term.”

In a recent report, Energy UK identified a number of ways the government could lower electricity bills during the current parliament, listed in the table below.

These can be categorised into optimising the energy system, investing public money in a “strategic and targeted way” and capitalising on the benefits of a smarter, more flexible host of technologies in the energy sector.

For example, Energy UK says that households with equipment such as a battery, a heat pump or an electric vehicle (EV), could save £115 per year if changes are made to maximise flexibility. This might mean charging the EV at night or warming the house in advance of periods with high electricity prices.

Additionally, it says flexibility could be used to reduce the need to build out networks and power stations to meet peak demand, potentially reducing the need for investment by £3.5bn.

| Option | Cost | Savings |

|---|---|---|

| Maximising flexibility | None | At least £115 per year for households with flexibility equipment |

| Closer UK-EU cooperation on energy | None | Up to £370m reduction in overall energy costs. Total savings for the economy are likely to be around £10bn this parliament |

| Modernising system operation | Small investment in NESO systems | Full savings are hard to quantify. Likely billions of pounds in efficiency savings this parliament. |

| Rebalancing policy levies for domestic users | £1.5bn per year (reducing from 2027 as RO & FiT taper off) | Up to £400 a year to households using electric heating, while guaranteeing that no households see an increase in cost. |

| Targeted consumer support | £1.5bn per year | £400 per year for the 3.17m households currently in fuel poverty, closing the fuel poverty gap completely. |

| Invest in energy efficiency | £13.2bn already committed in Labour manifesto | £140 per year is the average saving to a household from schemes such as ECO and GBIS. A Warm Homes Plan targeted at measures such as clean heat and solar is likely to achieve larger bill reductions. |

| Make the most of Contracts for Difference | Negligible | Up to £20 per year for the typical household. |

| Optimise network investment | Negligible | Almost £100 per year. |

| Electrify non-domestic demand | £1-4bn to be covered by hypothecated ETS/CBAMM revenues and general taxation | Level of bill savings depends on the nature of the business. UK supermarkets could save up to 15% on their energy costs. |

| Unlock private investment | Negligible (credit guarantees) | Full savings are hard to quantify. Likely to enable a minimum reduction of £150m in CfD costs. |

Energy UK’s table of options to reduce electricity bills in the UK in the short term. Source: Energy UK.

(Following Energy UK releasing this advice, the UK and EU have signed a new energy cooperation deal. This includes exploring UK participation in the EU’s electricity trading platforms, because, “since we left the EU, we have traded electricity inefficiently, adding costs and friction”.)

The single-biggest way the government could reduce electricity bills would be to remove some or all of the policy costs they currently include – a total of £173 for the average household.

These costs could be paid for via general taxation, which is split more fairly between households on different incomes, or the government could “rebalance” bills by shifting levies onto gas.

At present, gas faces an implicit subsidy because resulting CO2 emissions do not face a carbon price. However, raising gas bills could have implications for fuel poverty, even if power prices drop.

Many other organisations have looked at how bills could be “rebalanced”, given that the UK’s net-zero target relies heavily on increased use of electricity and reduced reliance on gas. Many of these analyses examine options to ensure fuel-poor households are not disadvantaged.

Further options for cutting bills, beyond those considered by Energy UK, have been proposed by a number of other groups.

A recent report by thinktank Common Wealth, for example, suggested that gas power plants should be nationalised, in order to prevent owners holding the electricity market “to ransom”.

One final possibility is that bills could drop as a result of falling gas prices. The latest forecast from Cornwall Insight suggests that there will already be a small 7% drop in the Ofgem price cap from 1 July, as a result of slightly cheaper gas.

EU gas use is set to fall in the coming years, meaning that available supply could exceed demand by 43% by 2030 and 42% by 2040, according to projections from the European Commission.

At the same time, the IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook noted that analysts are expecting a glut of liquified natural gas (LNG) on the global market, as projects in the pipeline come on stream.

On top of this, US president Donald Trump is pushing for an even faster expansion of LNG exports, which could see European gas prices going down by up to 9% by 2030, according to November 2024 analysis from Aurora.

Cornwall Insight forecasts power prices will fall between 2024 and 2030, predominantly due to ample gas storage levels in Europe for the winter, alleviating previous supply security concerns – although they expect prices to remain higher than the pre-crisis 2021 levels.

Moreover, gas prices remain at the whims of geopolitical disruption and a drop cannot be taken as a guarantee. In Cornwall Insight’s most recent power price forecast, Dr Craig Lowrey, principal consultant at the organisation, said:

“We mustn’t get ahead of ourselves. While prices are falling, recent patterns show the impact that wholesale market volatility can have on bills in the space of just a few days. The UK’s heavy reliance on energy imports – particularly gas – combined with ongoing geopolitical tensions, ensure household bills remain highly vulnerable to sudden shocks.

“To secure the UK’s energy future and drive down costs for good, we must break free from volatile international markets and fast-track the transition to renewables.”

Despite the clear impact of gas on UK power prices and energy security – and the lack of any evidence to suggest it would be good for bills – several prominent politicians have recently called for a slower transition to renewable energy. (See: What will the UK’s climate goals mean for bills in the future?)

Paul Drummond, climate and environment research lead at asset manager Redwheel, tells Carbon Brief that sticking with gas would leave the UK exposed. He says:

“We wouldn’t be solving any of the problems we have now. We’re still going to be significantly reliant on the gas price setting the power price – and as we’ve seen in the last few years, that has been highly volatile. That volatility in itself is a cost. It’s uncertain. So we wouldn’t change the situation we’re in now, which is not a great position to be in.”

Beyond household energy bills, Energy UK has produced a list of recommendations for reducing electricity prices for non-domestic users. This includes shifting legacy policy costs and Climate Change Levy payments away from electricity bills, among other actions.

Additionally, the government is reportedly looking at plans to help shield industry from “sky-high energy costs in what is expected to be the centrepiece of Keir Starmer’s vaunted new industrial strategy”, according to the Financial Times.

The industrial strategy is set to be published in June.

A coalition of manufacturers, investors and climate groups recently called on chancellor Rachel Reeves to move policy costs, which would include green levies, off electricity prices and into general taxation. They argued that this would cut business energy costs by up to 15% and household bills by up to £370 per year.

What will the UK’s climate goals mean for bills in the future?

At the heart of debates over the causes of high electricity prices are different views on the future path of the UK’s energy system.

The UK’s Labour government is targeting a “fully decarbonised” power system by 2030, setting a goal for clean sources to meet 100% of domestic demand and account for at least 95% of electricity generation in the country.

To reach these targets, it has laid out plans for a massive expansion of wind and solar power, along with steep increases in energy storage capacity and flexible low-carbon generation.

The government’s 2024 plan suggests it would require a programme of investment in clean power and associated infrastructure worth around £40bn per year until the end of the decade.

During campaigning and after being elected last summer, the Labour party had stated that this transition to clean electricity would save “up to £300” on household energy bills.

More recently, however, the party has gone quiet on this specific number. Speaking at an event run by the UK government and the IEA in April, energy secretary Ed Miliband said:

“Our vision of low-carbon power goes well beyond the climate imperative – important as that is. Homegrown low-carbon power is our nationally chosen route to energy security. Solar power, wind power, tidal, geothermal, nuclear power – also an essential part of the low carbon opportunity. These are often unlimited, low-cost power supplies which we can exploit for the benefit of our citizens.”

While the short-term picture is relatively uncertain, there is credible analysis to suggest that the government’s push for clean power will leave bills lower than or consistent with their current levels.

In its Clean Power 2030 report on reaching clean power by 2030, system operator NESO highlights that the overall cost to consumers “would not increase as a result of the move to a clean power system”.

Instead, it says that the much-reduced role for gas in a clean power system would be responsible for an increasingly small percentage of the wholesale costs protecting the country from price swings, the operator notes.

In one of the scenarios set out by NESO, gas would set the price in just 15% of hours by 2030, insulating consumers from “volatile international gas prices”.

It states that without accelerated action towards clean power, a repeat of the sort of gas price spike seen in 2022 would add around £22bn to electricity costs in 2030.

If the clean power mission is successful, it says, this cost would be cut in half and price spikes would be less likely.

(NESO does note that “how costs flow through to prices and, ultimately, bills, will depend on policy design”.)

As highlighted by research by Ember and E3G, deploying renewables “at speed” helps lower bills and increase energy security.

According to consultancy Aurora, a total of £116bn will need to be invested between 2025-35 to reach Labour’s 2030 clean power target, or around £10.6bn per year.

Despite criticism of the impact of bringing forward the target date, Aurora’s analysis suggests that it would require just an extra £1bn of investment a year to achieve the target five years earlier.

Aurora found that consumer energy bills will be lower under Labour’s 2030 target than under a 2035 goal.

In the longer term, there is more widespread agreement that a clean energy system – predominantly using electricity for heat, power and transport – would reduce overall energy costs for the UK.

For example, thinktank E3G suggests that the UK’s clean power “mission” could cut bills could fall by £200 by 2030, while consultancy DNVGL expects bills to fall 40% by 2050.

In contrast, the Conservative party has recently ended cross-party support for the UK’s net-zero-by-2050 target, launching an intensifying attack on clean energy.

Party leader Kemi Badenoch falsely claimed in a recent speech that the UK’s current climate policies are “driving up the cost of energy”.

Similarly, Reform UK has argued that net-zero policies are to blame for higher energy bills and that it would scrap the 2050 target if elected. In its manifesto in June 2024, it claimed, without evidence, that scrapping net-zero would save “over £30bn per year for the next 25 years.”

In contrast, asked if rowing back on climate action would reduce bills, Energy UK’s Vyas tells Carbon Brief: “No – not least because we’re only part way through the job and haven’t realised the full benefits yet.” She adds:

“Investing in clean power is crucial if we are to make progress on tackling climate change and achieving energy security. People across the country are clear that they want cheaper bills – and they want to see action when it comes to tackling the climate crisis. Of course, we need to go at a pace we can manage in practical terms and make sure that the costs of the transition are paid fairly.”

In a post on LinkedIn, Vyas’s colleague Adam Berman, director of policy and advocacy at Energy UK, writes that the “mental gymnastics” needed to believe it would be cheaper to stick with gas for electricity, instead of shifting to clean power, is “truly remarkable”. He says:

“If you genuinely believe gas is cheaper than clean power over an extended period of time, how do you reconcile that with the £100bn the UK government spent supporting homes and businesses during the energy crisis? The mental gymnastics required to ignore this are truly remarkable.”

In the longer term, electrification is key to net-zero, helping the UK to decarbonise not just its electricity system, but sectors including transport and heating at pace and in the most economical way.

Speaking at the UK government and IEA event in April, Emma Pinchbeck, the chief executive of the Climate Change Committee (CCC), said that electrification with clean power was vital to the UK’s climate targets and energy security, but was also the cheapest option to pursue.

The impact of clean power on lowering household bills is supported by the CCC’s recent advice to the government, which suggested the transition to net-zero would cut average household energy bills to £700 below today’s levels by 2050.

Additionally, the CCC said it would cut household motoring costs by a similar amount, thanks to EVs being much cheaper to run than petrol or diesel alternatives.

Vyas tells Carbon Brief that the best way to lower bills in the long-term will be to decarbonise the power system and to electrify energy end use, such as heat and transport. She says:

“The focus has to be on taking action that will make it quicker and easier to do two things. The first is to decarbonise our power system, encouraging investment in generation, storage, infrastructure and other technologies, tackling barriers that cause delays, such as planning and consents. And the second is to electrify – with a big focus on decarbonising the way we heat homes and buildings, as well as the way we power our transport.”

Much of this impact comes from reducing the UK’s need for fossil fuel imports, as well as improving energy efficiency. Analysis by ECIU highlights that renewables have already cut the UK’s dependence on foreign fuels for electricity generation from 65% in 2014 to under 50% today.

A report from the IEA last year similarly concluded that accelerating climate action towards net-zero “could lead to major reductions in household energy bills” around the world.