Simon Evans

21.07.2014 | 11:25amIs it possible to predict the future of UK energy?

A couple of weeks ago, the Guardian reported National Grid forecasting energy prices will double by the end of the decade. Other media reported the grid operator found that UK shale gas could supply much of our future needs, the UK’s gas supply could be held to ransom by Russia, solar power will fail to take off, and the UK can afford to meet green energy goals.

It all sounds quite colourful. So does National Grid really expect to see such wildly different events unfolding in the near future?

Well, no. The media reports were based on a series of scenarios prepared by the grid operator. To understand the difference between scenarios and forecasts – it goes beyond mere semantics – we take a look at why it’s so difficult to predict the energy future, and why such a range of possibilities are thrown up when we try.

Future planning

National Grid runs the UK’s core electricity and gas transmission networks. It is also responsible for balancing supply and demand in order to keep the lights on. That means it needs to plan ahead.

Every year it produces a set of Future Energy Scenarios that attempt to look into the future. This is a pretty mammoth task and National Grid analysts aren’t experts across the whole energy sector, so much of the work is based on what other people tell them. Experts, campaigners and even members of the public are invited to contribute their knowledge to the scenarios’ development.

The approach doesn’t keep everyone happy. For example, the solar industry says the range for solar capacity in the scenarios – between 8 and 17 gigawatts in 2030 – is way too low. WWF also thinks National Grid has got it wrong, but in a different way. It says National Grid is wrong to assume that all coal-fired power stations will close by 2023. Such are the perils of mapping the future.

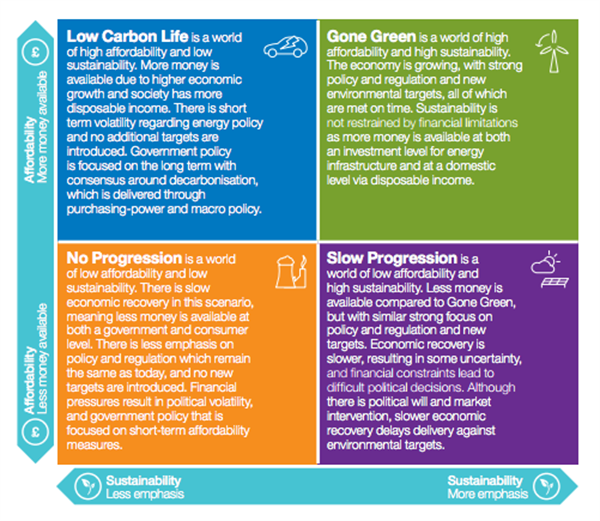

There are four scenarios, and they’re quite different. We’ll let the grid describe them in its own words, in the table below:

Source: National Grid Future Energy Scenarios 2014

So which scenario is most likely? National Grid can’t say, and that’s the point, market outlook manager Gary Dolphin says:

“We would need psychic powers to decide between the different scenarios. For us, that would be really useful information. The bad news is we’re not psychic.”

Dolphin says:

“We do not apply probabilities to any of our scenarios. We like to believe each scenario is equally plausible and that they collectively define an envelope within which the true future lies.”

Can’t we get a better answer?

If that sounds a bit wishy-washy, maybe someone else has a more definitive answer?

A bunch of other institutions including BP, Shell, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) and the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) have come up with their visions of what the future of energy might look like. Here’s a great webpage with a long list of different international efforts.

Trying to decide which scenario is most plausible is nightmarishly difficult. Some don’t have UK-specific analysis, for starters. Another issue with making comparisons is the differences in approach.

Some scenarios are based on detailed economic models, which brings a whole new set of complications. Modellers like to say ‘garbage in, garbage out’ because the results can only be as good as the information fed into the model.

Typically you will need to tell the model about the future cost of energy, the relative price of coal versus gas, the cost of building wind turbines or solar panels and the price of carbon – among many, many other variables.

These are all assumptions made by the modellers. Just because they’re using a complicated model doesn’t make the assumptions correct.

Last year UKERC ran a comparison of several model runs to see why they were giving such different answers.

What UKERC found is that “quite small changes in assumptions can produce quite large changes in outcomes.” So conclusions about which electricity-generating technologies will be most cost-effectiveness in future are “unlikely to be robust”, UKERC says.

Future wind capacity

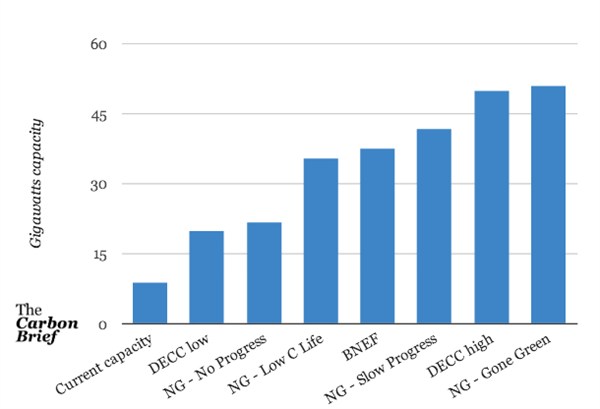

To illustrate this point let’s look at some different visions for the future of UK wind power.

Depending who you ask there will be anything between 20 and 51 gigawatts of wind capacity in 2030, as the chart below shows. That’s between two and six times the current level.

Source: Carbon Brief comparison of DECC, National Grid and BNEF data

If you want to know what the future of UK energy looks like, an answer that varies so much isn’t very helpful. UKERC argues that it’s only worth relying on consistent results that pop out of different visions of the future, even when assumptions are varied.

It says two examples of consistent results are that energy efficiency always comes out cheaper in energy models than building an equivalent amount of new generating capacity, and that the most cost-effective path to the UK’s 2050 climate goals includes a decarbonised electricity mix in 2030.

Future power prices

Another key assumption in energy futures models is the price of energy. The National Grid scenarios use a range of future wholesale electricity prices. The range includes prices doubling to around £100 per megawatt hour in 2030, but also a low price case where prices stick at the roughly £50 per megawatt hour level we have today.

DECC’s central policy projection assumes prices will rise in future, continuing the trend of recent years of rising demand and tightening supplies. Others, like prominent economist Professor Dieter Helm and ratings agency Moody’s, believe prices will stay low.

Who is right has huge knock-on effects on DECC’s plans to subsidise renewable electricity supplies, because it is offering a top-up on wholesale prices up to a fixed level known as the ‘strike price’.

This amounts to a bet on high wholesale prices. If prices remain low – as Moody’s and Helm suggest – the top-up bill will be much higher. That means DECC’s subsidy budget, which has a cap of £7.6 billion in 2020, could run out.

One analyst that takes this danger seriously is Jon Ferris, head of risk management for energy consultancy EIC. He says there are a range of factors that will tend to drive future wholesale prices down in the UK. For instance, rising renewables capacity drives prices down because the marginal cost of a unit of electricity from a windfarm is close to zero.

Ferris says:

“DECC’s expectation of rising prices is contradicted by recent German experience, where wholesale prices are at nine-year lows and have gone down as more renewable capacity has been added.”

Adrian Gault, head of the Committee on Climate Change tells Carbon Brief that DECC has allowed for a 20 per cent buffer in its 2020 budget. This is a sufficient buffer to cover the subsidies necessary to meet renewable energy targets even if prices stay low, he says.

Ferris argues things will be tight even if you include the buffer. He also points out that it would be a big political risk to stretch the already large £7.6 billion budget up to £9.1 billion.

So what will the future look like?

Everyone wants to know what the future of UK energy will actually look like. Our ability to deliver energy security, keep energy bills affordable and meet climate targets is riding on the answer. Yet National Grid and multiple other sources have given us a huge range of plausible outcomes instead of the simplicity of a single answer.

Richard Smith, National Grid head of energy strategy and policy says it’s a question of being unable to do predict the future with any confidence. He tells Carbon Brief: “If we could, we’d be presenting forecasts not scenarios.”

Smith has compared National Grid’s scenarios with those from other analysts. Some lean one way, like those from oil firms BP and Shell. Others, like BNEF, have a different take. As should now be clear, these differences are more a reflection of the assumptions and biases of those that produced them. It should be no surprise that oil firms favour fossil fuel-heavy futures while analysts with ‘new energy’ in their name favour things like wind and solar.

Smith says he’s 80 to 90 per cent confident the future will lie within the range of outcomes described by National Grid’s scenarios. He’s not willing to stick his neck out any further.

One of National Grid’s analysts puts it like this:

“We used to do forecasts. The only thing you can say about them is that they’re going to be wrong.”

You’ve got to hand it to National Grid and the others who have made huge, time-consuming attempts to gaze into the crystal ball. They’re bound to be wrong – the best they can hope for is to have been useful too.