AI: Five charts that put data-centre energy use – and emissions – into context

Josh Gabbatiss

09.15.25Josh Gabbatiss

15.09.2025 | 4:26pmArtificial intelligence (AI) has undergone a rapid expansion in recent years.

Tech leaders have hailed an “AI revolution” – predicting “transformative” effects for humanity – while some governments have set their sights on AI-driven economic growth.

Yet, the industry is also facing scrutiny on many fronts, from inaccuracies in AI outputs through to the threat it poses to democracy.

One major critique concerns the environmental impact of AI, particularly the intensive energy use and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of the data centres that power it.

Campaigners, journalists and researchers have warned that the rapid expansion of data centres could slow down or even reverse the global shift towards net-zero.

The topic is complex, not least because the future of AI – and the role it could play in increasing or potentially helping to reduce emissions – remains highly uncertain.

Below, Carbon Brief takes a look at some of the best available figures, largely from the International Energy Agency (IEA), to explore the energy and emissions impact of AI.

- Data centres currently account for a small share of global emissions and electricity use

- Around a tenth of the electricity demand growth by 2030 is set to be driven by data centres

- Data centres could account for half of electricity demand growth in some countries

- Fossil-fuel use will likely expand to power data centres, but clean-energy supplies are set to grow faster

- There is a lot of uncertainty about how much data centres will expand

1. Data centres currently account for a small share of global emissions and electricity use

The process of training and deploying AI models relies on data centres – large, energy-intensive facilities that house computing infrastructure.

Data centres already underpin the internet, among other things, making them essential for modern life. But as hype around AI has grown in recent years, investment in new data centres has ballooned.

The global electricity consumption of expanding data centres has grown by around 12% each year since 2017, according to the IEA’s recent “energy and AI” report.

Concerns about “skyrocketing” electricity demand have also prompted warnings of data centres driving up CO2 emissions, as fossil fuels still generate much of the world’s power.

Indeed, companies, such as Google, Meta and Microsoft, have reported large emissions spikes over the past few years due to data-centre expansion, despite their net-zero pledges.

One research paper concludes that the electricity demand of AI “runs counter to the massive efficiency gains that are needed to achieve net-zero”. Others have voiced concerns that data centres will “overwhelm” and “undermine” both national and company-level climate targets.

Reporting often mentions the electricity demand of data centres – or their emissions – “doubling”, “tripling” or increasing by some other large percentage in the coming years.

But these increases, while potentially dramatic in relative terms, are starting from a low baseline. As shown in the chart below, data centres are currently responsible for just over 1% of global electricity demand and 0.5% of CO2 emissions, according to IEA data.

Given this starting point, even as data centres expand, the IEA suggests that they will make a relatively small contribution to climate change, in the short term.

The agency estimates that data-centre emissions will reach 1% of CO2 emissions by 2030 in its central scenario, or 1.4% in a faster-growth scenario.

Nevertheless, it notes that this is one of the few sectors where emissions are set to grow – alongside road transport and aviation – as most will likely decarbonise in the coming years.

2. Around a tenth of the electricity demand growth by 2030 is set to be driven by data centres

The world is entering what the IEA describes as a “new age of electricity”, in which the electrification of transport, buildings and industry drives a surge in demand for power.

Along with electric cars and factories, data centres are frequently highlighted by analysts as a key “emerging driver” of this demand.

Under the IEA’s central scenario for data-centre growth, the sector’s global electricity consumption would more than double between 2024 and 2030, reaching 945 terawatt-hours (TWh) by the end of the decade. This is equivalent to the current electricity demand of Japan.

The IEA describes AI as “the most important driver of this growth”.

As it stands, AI has been responsible for around 5-15% of data-centre power use in recent years, but this could increase to 35-50% by 2030, according to another report prepared for the IEA.

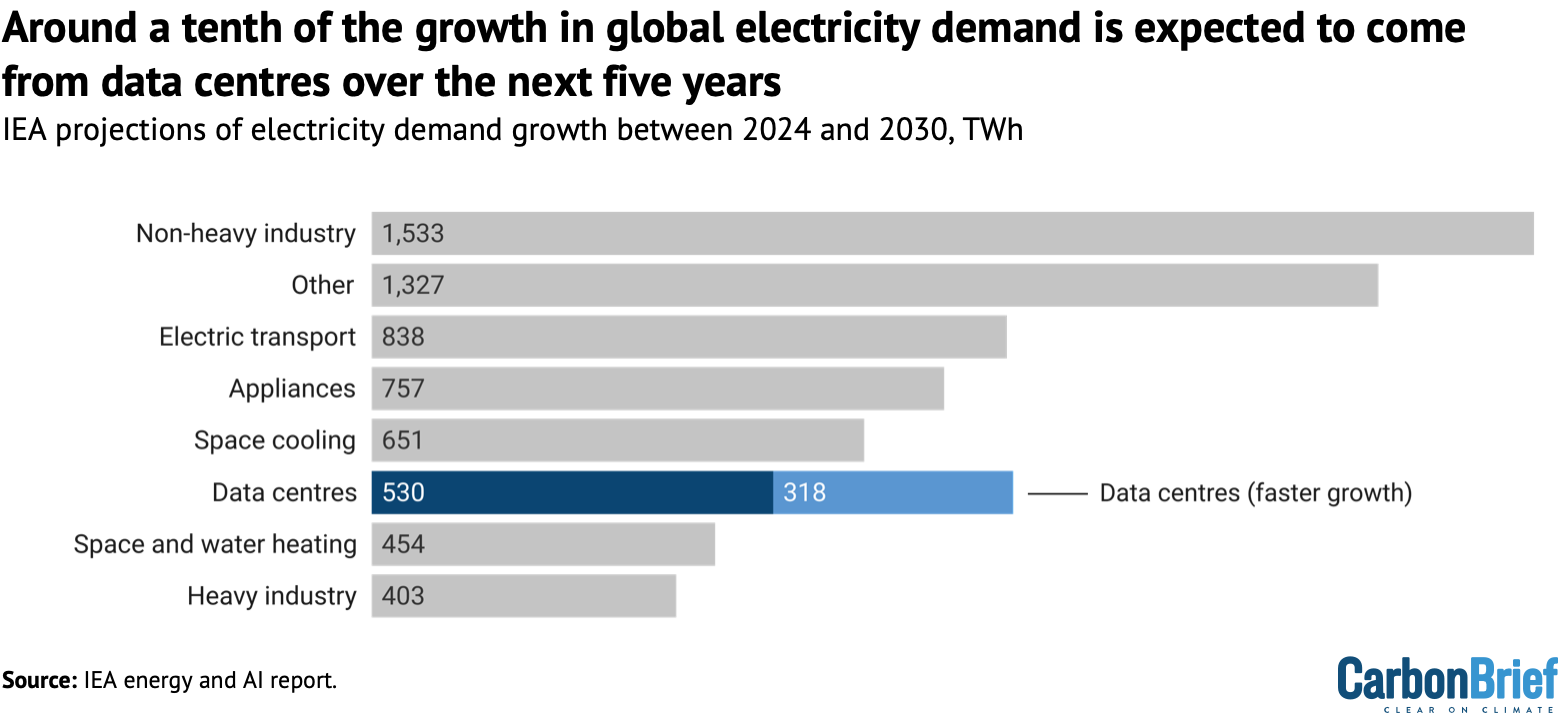

However, the 530TWh rise in electricity demand in data centres by 2030 would only be 8% of the overall increase in demand that the IEA projects, as shown in the chart below.

This is less than electric vehicles (838TWh) or air conditioning (651TWh). It is considerably less than the 1,936TWh growth expected in industrial sectors by 2030.

If data-centre electricity use rose in line with the IEA’s faster-growth scenario, the facilities would be responsible for around 12% of global demand growth overall.

While the IEA says “uncertainties widen” when considering electricity demand growth beyond 2030, it expects a continued – albeit slower – increase to 1,193TWh by 2035.

This would mean annual demand growth roughly halving, from around 90TWh per year out to 2030, down to less than 50TWh a year out to 2035.

3. Data centres could account for half of electricity demand growth in some countries

While the global picture suggests a relatively modest role for data centres in driving near-future electricity demand growth, it could be far more pronounced in some countries.

Data centres are very geographically concentrated, both in terms of their global distribution and within leading countries. Today, nearly half of their electricity consumption takes place in the US, 25% in China and 15% in Europe, according to the IEA.

US data centres used around 4% of the nation’s electricity in 2023 and this is set to rise to 7-12% by 2028, according to analysis by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

In Ireland – regarded as a European “tech hub” – around 21% of the nation’s electricity is used for data centres. The IEA estimates that this share could rise to 32% by 2026.

Data-centre electricity demand tends to be further localised in certain regions. In the US state of Virginia, these facilities already consume 26% of electricity, while in the Irish capital, Dublin, the figure is 79%, according to analysis by Oeko-Institute.

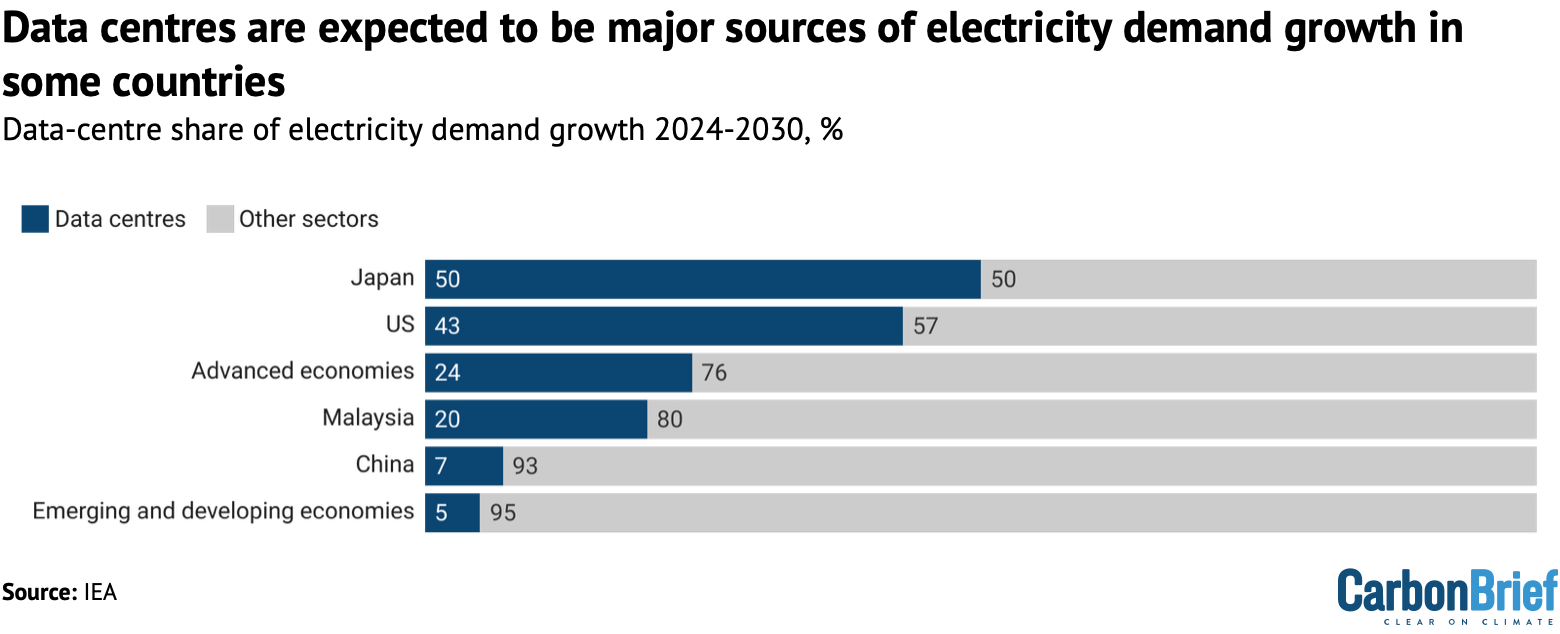

Much of the commentary on AI threatening climate goals comes from “advanced economies” in the global north, where the IEA estimates that, on average, a quarter of electricity demand growth by 2030 will be driven by data centres.

(In many of these countries, electricity demand has previously been flat or falling for years.)

Roughly half of the power demand growth in the US and Japan over the next five years is expected to come from data centres, according to the IEA, as shown in the figure below.

While there are some notable exceptions, such as Malaysia, data centres are set to be a relatively small portion of electricity demand growth in developing and emerging markets.

Around the world, electricity grids are under strain, with many developed countries, in particular, seeing long wait times for grid connections and new transmission lines. Data-centre growth is raising this pressure.

There are also growing concerns, notably in the US, about the impact data-centre growth could have on energy bills.

The IEA says that demand growth presents “advanced economies” with a “wake-up call” for the electricity sector to invest in infrastructure, otherwise “there is a risk that meeting data-centre load growth could entail trade-offs with other goals, such as electrification”.

4. Fossil-fuel use will likely expand to power data centres, but clean-energy supplies are set to grow faster

The extent to which data-centre growth increases emissions depends on which energy sources power those data centres.

Data centres can use power from the grid, in which case their electricity mix will reflect that of the region they are in and could therefore become cleaner as nations decarbonise.

They can also be powered by “captive” sources, built to supply specific facilities, such as solar panels, small nuclear reactors or gas turbines.

There are concerns that data-centre expansion will be used to justify the prolonged use of fossil fuels, “locking in” a future of elevated emissions.

Indeed, the likes of Shell have framed AI in such terms and some data-centre operators have been explicitly seeking gas connections to meet their electricity needs.

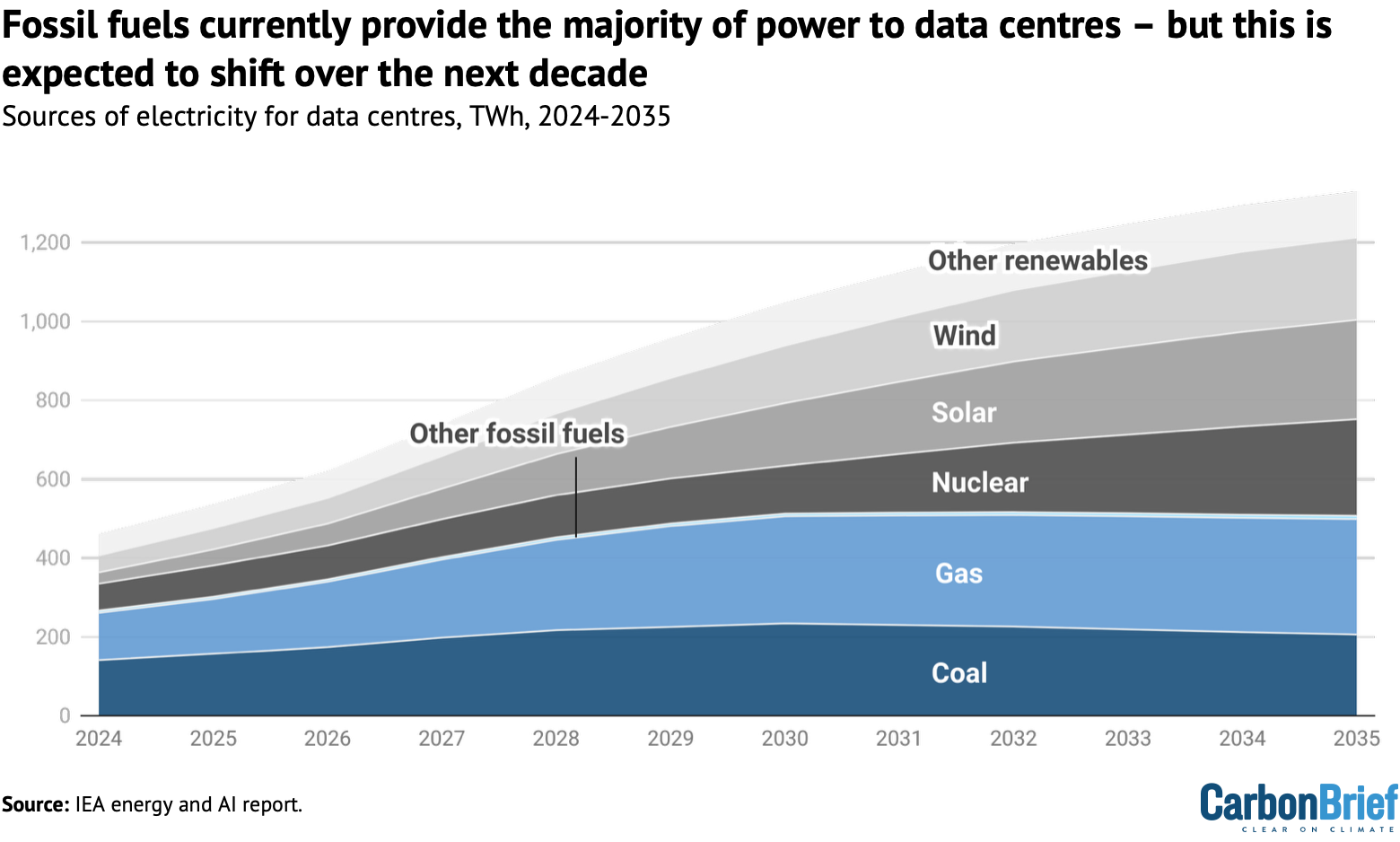

Currently, coal is the biggest single electricity source for data centres globally, largely due to the numerous facilities in China.

Overall, fossil fuels provide nearly 60% of power to data centres, according to the IEA. Renewables meet 27% of their electricity demand and nuclear another 15%.

(These figures are based on the electricity these facilities consume, rather than any contracts they have to buy clean energy credits.)

In the IEA’s central scenario, by 2035 the ratio of the data-centre electricity mix switches from around 60% fossil fuels and 40% clean power to 60% clean power and 40% fossil fuels, as shown in the chart below.

This is expected to be driven primarily by the wider global expansion of renewables, although some projects will be funded directly by data-centre companies.

However, the IEA says significantly more gas and coal power would likely still be required to meet data-centre demand, both from ramping up existing plants and building new ones.

Gas-power generation for data centres is expected to more than double from 120TWh in 2024 to 293TWh in 2035, with much of this growth in the US, according to the IEA.

About 38GW of captive gas plants currently “in development” – roughly a quarter of all such projects – are planned to power data centres, according to Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

The US has doubled the amount of gas- and oil-fired capacity it has in development over the past year, driven partly by the energy demand of the “burgeoning AI industry”, according to GEM.

However, these projects are facing long lead times and “sharply” rising costs, with GEM noting, as a result, that many may never materialise.

5. There is a lot of uncertainty about how much data centres will expand

Currently, there are no comprehensive global datasets available on data-centre electricity consumption or emissions, with few governments mandating any reporting of such numbers.

All figures concerning the energy and climate impact of AI are therefore estimates.

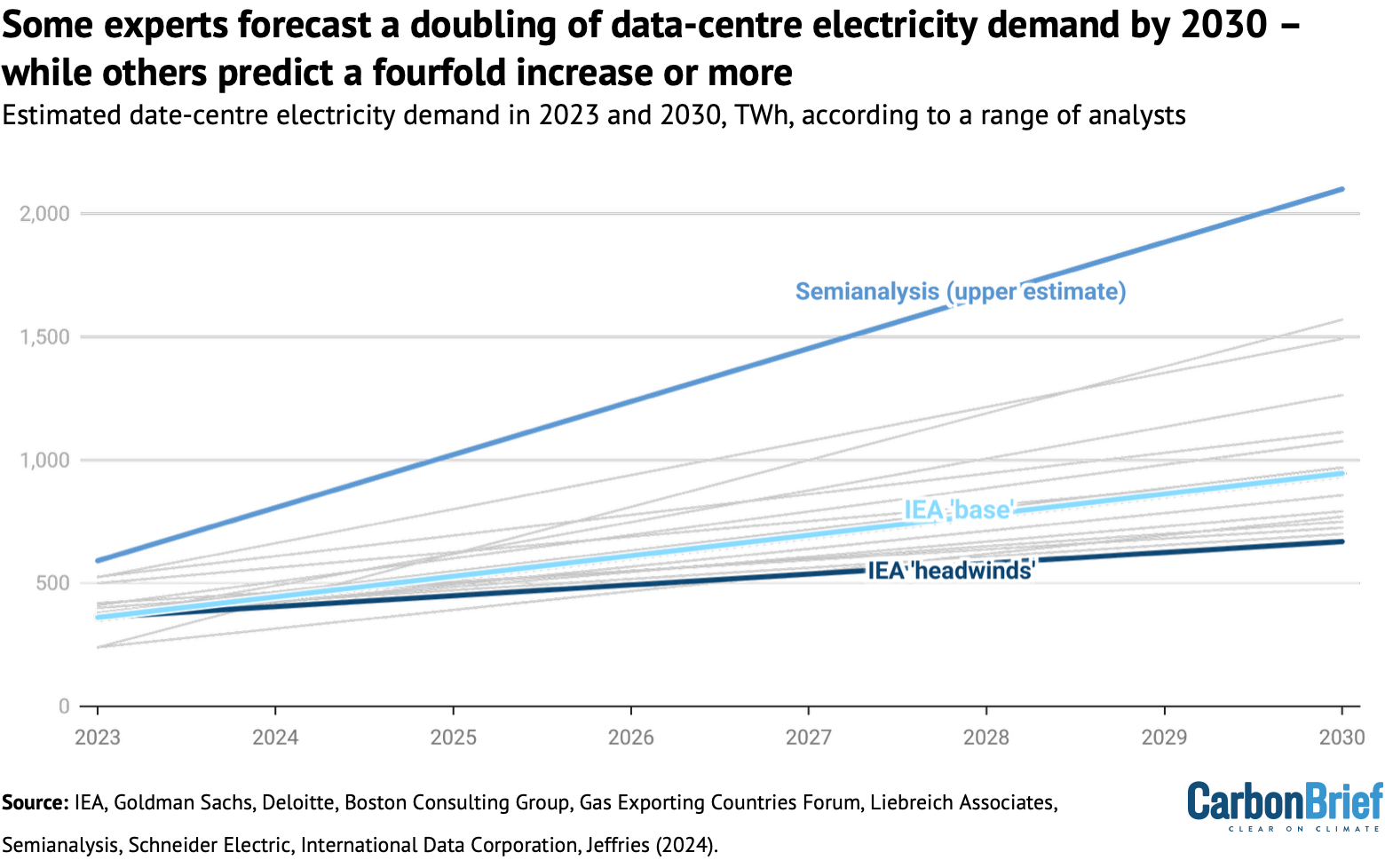

The IEA has assessed hundreds of available estimates and forecasts, noting that even historical data can be “widely divergent”, due in part to a lack of common definitions.

On top of this, there are major uncertainties, including over how quickly AI will be adopted. Despite the enthusiastic uptake of generative AI by individuals and companies, some argue that the business case for continued, rapid growth may be weaker than suggested.

Another uncertainty is how energy-efficient AI will be. Experts have already identified efficiency improvements resulting from better chips, more efficient training algorithms and larger data centres, all of which could continue curbing electricity demand.

(Google has also reported a substantial drop in the electricity use required for individual AI search queries, which is already small compared to the power needed to train AI models.)

A final uncertainty is over how many proposed data centres will actually get built, with some speculative requests for grid capacity relating to plans that may never materialise.

As a result of these knowledge gaps, there have been numerous estimates of short-term electricity demand growth from data centres, which have produced very different results, as shown in the chart below.

Some estimates – such as one from the Gas Exporting Countries Forum arguing that more gas exports will be needed to fuel meteoric rises in electricity demand for AI – have been deemed less credible in reviews by independent experts.

Another area of great uncertainty concerns the impact that the application of AI could have on electricity use and emissions.

Some researchers have attempted to calculate how much AI could curb emissions, by helping to identify efficiency gains in other parts of the energy system, or by making technological breakthroughs.

In some “exploratory” analysis, the IEA says such gains could cancel out any extra data-centre emissions due to the growth of AI.

However, it adds that despite the AI hype, “there is currently no existing momentum of AI adoption that would unlock these emissions reductions”.