Analysis: Only half of Chinese provinces finalise key ‘Document 136’ renewable rules

Anika Patel

10.15.25Anika Patel

15.10.2025 | 3:52pmOnly half of China’s provinces have finalised new rules for pricing wind and solar power, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Local governments are required to have published final plans to reform the way wind and solar power is priced in their jurisdiction before the end of this year.

This follows the release of a central government directive in February – known as “Document 136” (136号文) – that calls for developing a more “market-based” approach to pricing newly installed renewable projects.

The new rules will replace the previous pricing mechanism, which gave wind and solar generators guaranteed sales at a fixed price tied to the benchmark electricity price from coal.

The shift towards market-based pricing for wind and solar is seen as a key uncertainty for the sector, with implications for China’s wider energy and emissions targets.

Carbon Brief analysis finds that, as of 15 October 2025, only 18 provinces had issued finalised “Document 136” plans.

Another 10 have published draft plans, while Jiangsu, Tianjin and Tibet have yet to indicate what their strategies will be.

Central direction, local rules

In February this year, China’s central government issued a notice on “deepening market-based reform of feed-in tariffs for new energy”, also known as “Document 136”.

The document calls on local governments to develop plans for new pricing mechanisms for wind and solar power, applicable to projects completed on or after 1 June 2025.

Local governments are expected to develop “sustainable new-energy pricing mechanisms” (新能源可持续发展价格结算机制), in which they only offer a fixed price to a set amount of new wind and solar capacity each year.

The amount offered a fixed price is to be linked to each province’s annual clean-energy installation quotas. Moreover, the fixed price is to be determined at auction, through a mechanism resembling the UK’s contract for difference (CfD).

Any additional wind and solar projects, which are unable to secure contracts via the provincial auction mechanism, would need to find buyers for their electricity on the open market. This could be done through a “power purchase agreement” with a grid operator or a large industrial user, for example, or by selling their power in spot markets.

The move is part of wider efforts to shift China’s giant electricity system towards more market-based operation, rather than running on rules set by the government, including prices for coal-fired power plants determined by bureaucrats.

The shift towards market-based pricing for renewables has been attributed to both the falling costs of building new solar and windfarms, as well as to the grid challenges created by record renewable capacity additions.

At the time of the policy’s release earlier this year, analysts expected the rules to have a chilling effect on China’s wind and solar buildout in the short term, as developers adjust to the new rules and to lower – and more uncertain – prices set at auction.

The notice led to a rush of new capacity additions ahead of the June cut-off, with an estimated 100 solar cells being installed every second in the month of May.

However, a subsequent policy requiring cement, polysilicon and iron and steel manufacturers, as well as certain types of data centres, to use renewable power to fulfil a certain proportion of their overall consumption has been seen as a “backstop” that may buoy industry demand for new wind and solar capacity.

Furthermore, analysts believe that “Document 136” may strengthen China’s clean-energy industries in the long term, by forcing companies to become more innovative and competitive.

Below, Carbon Brief lists which provinces have published finalised “Document 136” pricing plans (green), which provinces have published a form of draft plan (yellow) and which provinces have yet not published their plans at all (white).

By default, provinces are listed in order of the size of their energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, based on a dataset for 2022 from the thinktank Institute of Global Decarbonization Progress.

New territory

So far, Carbon Brief finds, only just over half of provinces have issued finalised plans. Collectively, these provinces account for 61% of China’s energy-related emissions.

Another 10, representing 31% of emissions, have published draft plans, while Jiangsu, Tianjin and Tibet – the final 8% of CO2 – have yet to publish anything.

A few provinces published finalised rules in early June, including renewable-power heavyweights Shandong and Inner Mongolia.

(Inner Mongolia’s power grid is split into two zones – “Inner Mongolia East” and “Inner Mongolia West” – which are administered separately.)

In a nationwide conference call at the end of August, National Energy Administration officials urged provinces to “promptly promote” concrete plans.

Eleven provinces have published finalised rules since then, including major polluters Heilongjiang, Hebei and Guangdong, with a further eight publishing draft rules, according to Carbon Brief calculations.

The delay in provinces completing their plans can be attributed to the fact that local policymakers are trying to establish a completely new system of pricing power from scratch, says David Fishman, principal at energy consultancy the Lantau Group.

He tells Carbon Brief that, for some of the provinces that have issued finalised rules, “fairly meaningful differences” can be found between the final version and earlier drafts – indicating a high level of debate on the best path forward.

Shandong province was the first to issue draft rules, setting the tone for other local governments’ documents.

The eastern province is seen as a leader both in renewable energy additions and in undertaking power-market reforms. It is also the largest source of energy-related emissions in China.

Its plan saw notable policy innovations, such as setting an auction subscription threshold of 125% to encourage competition, by ensuring that not all bidders will be successful.

In September, it also became the first province in China to hold auctions for solar and wind power under the new rules, with the winning bidders securing prices of 0.319 yuan per kilowatt-hour (yuan/kWh) for wind and 0.225 yuan/kWh for solar.

These prices are equivalent to £33.8 per megawatt hour (MWh), or $44.8/MWh, for wind and £23.8/MWh, or $31.6/MWh, for solar.

While the wind prices are seen as high enough to be relatively acceptable to project developers, the price for solar is below the level thought to be needed to finance such developments. As such, it could “discourage” further solar investment in the province, Reuters reports.

Shortly afterwards, the southwestern province of Yunnan also held its first renewables auction, setting a price of 0.33 yuan/kWh for both wind and solar projects.

Effect on future additions

Analysts disagree about what impact the “Document 136” policy will have on the pace of China’s clean-energy additions.

The country installed a record 360 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar in 2024, followed by an even higher 212GW in the first half of 2025 for solar alone, as developers rushed to complete ahead of the June deadline.

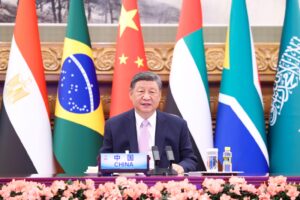

In September, Chinese president Xi Jinping announced a target of 3,600GW of wind and solar capacity by 2035 as part of the country’s new “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.

While hugely ambitious in the context of current global wind and solar capacity, which stood at 1,400GW at the end of 2024, this new goal is equivalent to just 200GW of new wind and solar per year. This would be a significant slowdown compared with China’s recent pace of expansion.

Dr Muyi Yang, senior energy analyst for Asia at thinktank Ember, tells Carbon Brief that he does not see the pricing reforms as a “signal of a structural slowdown in clean capacity [additions]”. He adds:

“Adding panels and turbines is the easy part…China is rewiring the world’s largest power sector, with multiple layers of interests and legacy assets to manage. In navigating this complexity, pledge targets act as a floor, providing certainty to clean-energy developers and clean-tech manufacturers. The NDC goal reflects what decision-makers are confident China can deliver given these constraints.”

But Fishman, writing on LinkedIn, notes that the pricing reforms could make it “challenging” for China to hit Xi’s new 2035 target.

Renewables developers are not incentivised to sustain previous years’ high installation figures under the local rules that have been rolled out so far, he notes, adding: “We will be lucky to see 200GW in a single year again for a long time.”

In its Renewables 2025 report, published in October 2025, the International Energy Agency (IEA) shaved 5% off its outlook for wind and solar growth in China out to 2030, a reduction of 129GW. It attributes this downgrade to the country’s renewable pricing reforms “impacting project economics and lowering growth expectations”.

Nevertheless, it adds that China is still projected to add “nearly 2,660GW” of new renewable capacity between 2025 and 2030, meaning that it would reach its 2035 wind and solar target “five years ahead of schedule”.

Bolstering storage demand

Beyond wind and solar capacity, “Document 136” also signalled potentially disruptive changes for China’s energy storage sector. It removed requirements at the central level that wind and solar projects must include a storage component.

This led to concerns at the time that demand for battery energy storage facilities could drop substantially.

In practice, however, different provinces have designed their own approaches to commissioning energy storage under their “Document 136” plans.

Some, such as Shandong, have eliminated energy storage requirements, while others, such as Yunnan and Guizhou have kept them.

A recent analysis by consulting firm Infolink argues that a significant drop in demand for energy storage projects is, therefore, “unlikely”, due to expected ongoing demand for “renewable integration and grid flexibility”.

Pumped storage and gas-fired power capacity make up only 7% of China’s electricity system – compared to 34% in Spain and 50% in the US, according to analysis by NGO Greenpeace. As such, it says there will likely be ongoing demand for battery storage as a major contributor to power flexibility in China.

The Chinese government set a target in a recent action plan for 180GW of new-energy storage by 2027, up from just over 100GW at the end of June 2025.

The target “directly addresses the issue of low short-term economic viability” of the energy storage sector caused by “Document 136”, economic news outlet Jiemian reports, although it notes that “uncertainties” still remain.

However, unnamed industry participants tell financial news outlet Yicai that the pricing reform has removed the storage sector’s “fig leaf”, meaning it is likely to result in the number of energy storage companies falling from the current figure of more than 200,000.

Yang tells Carbon Brief that the reforms will likely lead to “more storage-paired and hybrid projects” that better meet province-specific needs and “prioritise reliability and integration over headline [megawatts]”.