Analysis: Reform-led councils threaten 6GW of solar and battery schemes across England

Multiple Authors

06.16.25Multiple Authors

16.06.2025 | 3:45pmReform UK’s local-election victories in May 2025 could put 6 gigawatts (GW) of new clean-energy capacity at risk, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

The hard-right populist party took control of 10 English councils in last month’s local elections and has said it will use “every lever” to block new wind, solar and battery projects.

Those 10 areas have jurisdiction over 5,076 megawatts (MW) of battery schemes, 786MW of solar and 56MW of wind, according to Carbon Brief’s analysis of industry data.

While Reform has also pledged to “ban” battery systems, councils do not have direct control over these projects, which are determined by local planning authorities.

It could still influence local planning decisions, planning experts tell Carbon Brief.

However, this is likely to prove a “nuisance” with “limited effect” in terms of the government’s targets for clean power overall, according to one planning lawyer.

Opposing net-zero

Reform UK’s leaders are openly sceptical about the causes and consequences of human-caused climate change. The party is also explicitly opposed to the UK’s net-zero target, which, at a global level, is the only way to stop warming from getting worse, according to scientists.

The party has pledged to “scrap net-zero” if it ever takes power at the national level, falsely asserting that this would free up billions of pounds of public money for tax cuts and welfare programmes.

(Its assertions ignore the fact that the large majority of the investments needed to reach net-zero are expected to come from the private sector, rather than government funds. They also do not account for the economic benefits of lower fossil fuel use or avoided climate impacts. The party’s misleading claims have been widely dismissed by economists.)

Reform UK has also said it would “ban” battery storage projects and impose new taxes on solar and wind power installations.

As it stands, the party only has five MPs in parliament. However, its success in the recent English local elections and favourable polling numbers have raised its profile in UK politics and given it new powers in some areas.

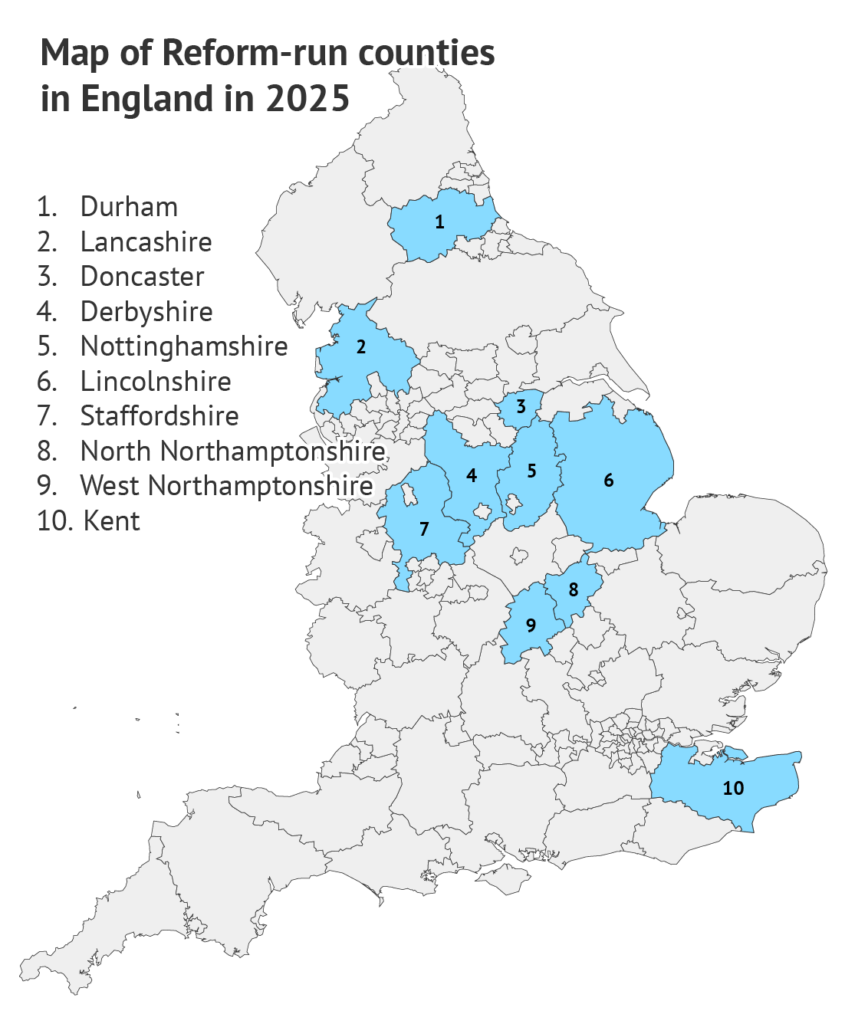

To assess the potential impact of these new powers on clean-energy expansion, Carbon Brief looked at data for 10 local councils where Reform UK won overall control, shown in the map below, including Durham, Kent and Derbyshire, as well as two mayoralties.

(The analysis does not include Warwickshire, where no party gained a majority in the elections. However, a subsequent vote saw the party’s local head selected to lead the county council. He has announced plans to “dumb down” net-zero initiatives in the county.)

Following the election, Richard Tice, Reform MP and deputy leader, said the party would use “every lever” available to block new renewable-energy projects in the areas it now controls.

At the heart of this commitment is Lincolnshire, the location of Tice’s own constituency, Boston and Skegness, which now also has a Reform-run council and a Reform mayor.

The rural county is the site of several large-scale solar project proposals, which have faced a strong backlash from some local people.

This mirrors a wider trend of opposition to solar and battery projects by campaigners, who say they are concerned about, what they allege, could be the impact on the local countryside and farmers.

However, such views are not the norm. Survey data shows overwhelming public support for solar and other renewables across the UK, even if projects are built in people’s local areas.

Analysis by thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit also noted that by rejecting net-zero-related projects, Reform UK could threaten thousands of jobs and millions of pounds of investment in areas such as Lincolnshire.

Capacity at risk

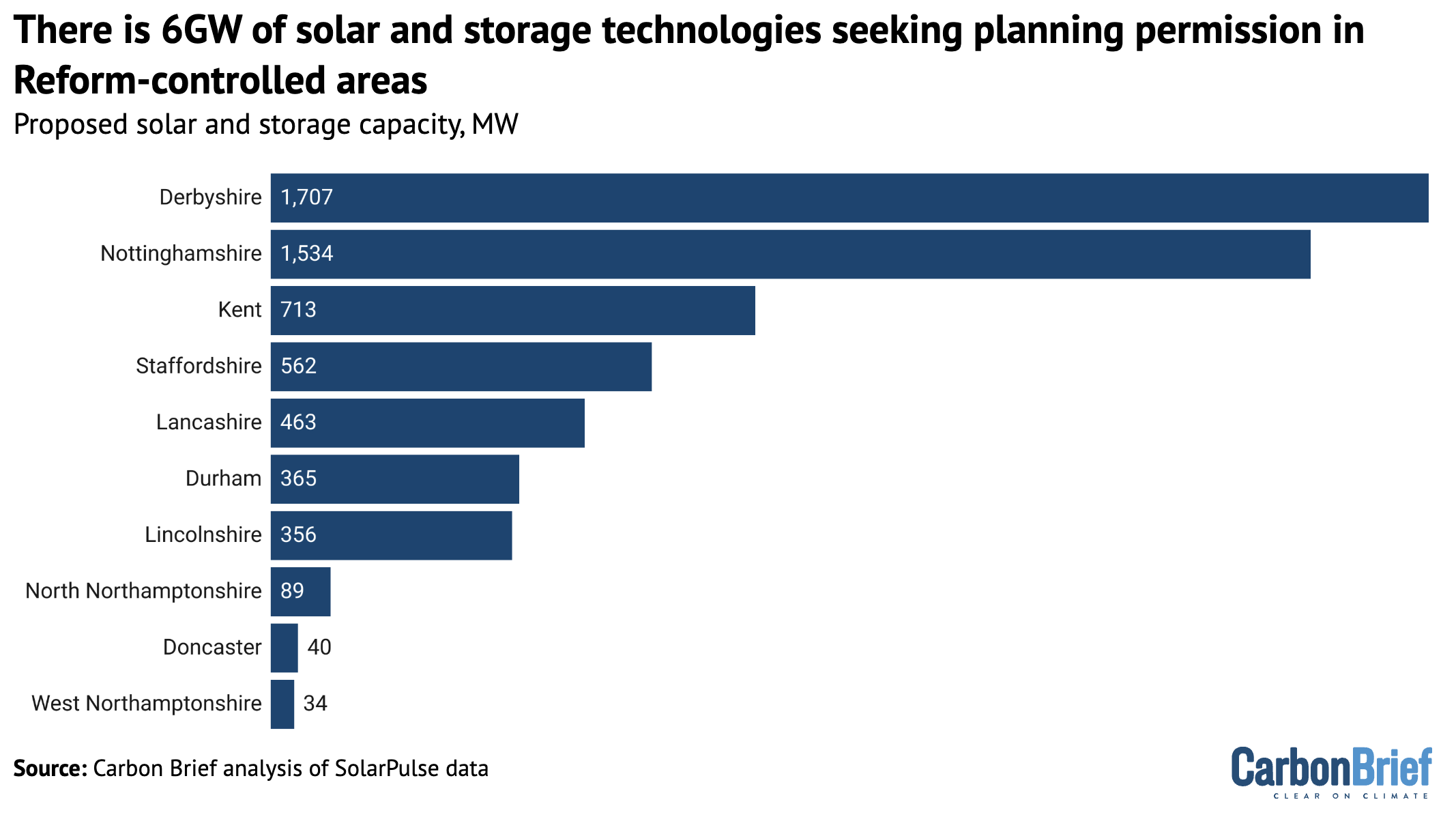

In total, some 5,862MW of solar and storage capacity is currently seeking local planning authority planning approval across the 10 Reform-controlled councils, Carbon Brief’s analysis shows. This is broken down by council area in the figure below.

This includes a series of smaller proposed solar farms, each with a capacity of less than 50MW, meaning they need local planning approval.

(The threshold for local planning approval, currently 50MW, is set to rise to 100MW in 2026.)

Solar farms above this capacity threshold go through the “nationally significant infrastructure planning” (NSIP) process. These large-scale projects are then assessed by energy secretary Ed Miliband, who can grant or deny a development consent order.

Local planning authorities (LPAs) are guided by the national planning policy framework (NPPF), rather than the politics of the county councils under which they sit.

However, the Reform-controlled councils overseeing these authorities will likely attempt to assert influence over approvals.

Gareth Phillips, partner at Pinsent Masons law firm and specialist in renewable energy planning and project development, tells Carbon Brief that, while county councils are not responsible for determining planning applications, they do have influence over the outcome.

He tells Carbon Brief:

“[Councils are an] important consultee, required to respond to statutory consultation…which gives the opportunity for county-council members to influence the planning decision…In the case of Reform, it is possible that its elected members may seek to rally support for opposing planning applications, perhaps leading campaigns against the proposals. The risk here is that it may give the perception of credence to opposing views.”

Phillips says that in addition to influencing planning authority decisions, county councils could issue new strategic planning guidelines for their areas. He explains:

“It will be for the LPA to decide what, if any, weight to place on the county council’s views, when determining the planning application. Over time, it’s possible that Reform-led county councils may propose so-called ‘core strategies’, i.e. planning documents setting out strategic level requirements and policy applicable to development proposals in its jurisdiction. Similarly, that policy would be a matter for the LPA to consider and decide how much weight to apply when determining planning applications.”

This risk is mitigated to some extent by the core strategies within the NPPF and the “national policy statements” for energy, he notes.

As such, while local planning authorities will be required to determine the approval or rejection of an application on the basis of wider policy considerations, Reform-led councils could still affect the decision. “Reform-led county councils would have a voice and opportunity to influence planning decisions,” says Philips.

Stand-alone battery energy-storage projects do not have a capacity cap for being processed by local planning authorities, following changes to the regulations in 2020.

However, a number of storage projects that are co-located with solar will be judged under the NSIP process, meaning councils will be unable to block their construction.

Solar strife

Carbon Brief’s analysis looks at projects that have submitted planning permission requests in the 10 Reform-controlled counties, using Solar Energy UK’s SolarPulse database for solar and storage.

The analysis also covers relevant onshore wind projects, based on data from the government’s renewable energy planning database.

(Solar Energy UK notes that the SolarPulse database does not include solar projects with a capacity of less than 5MW.)

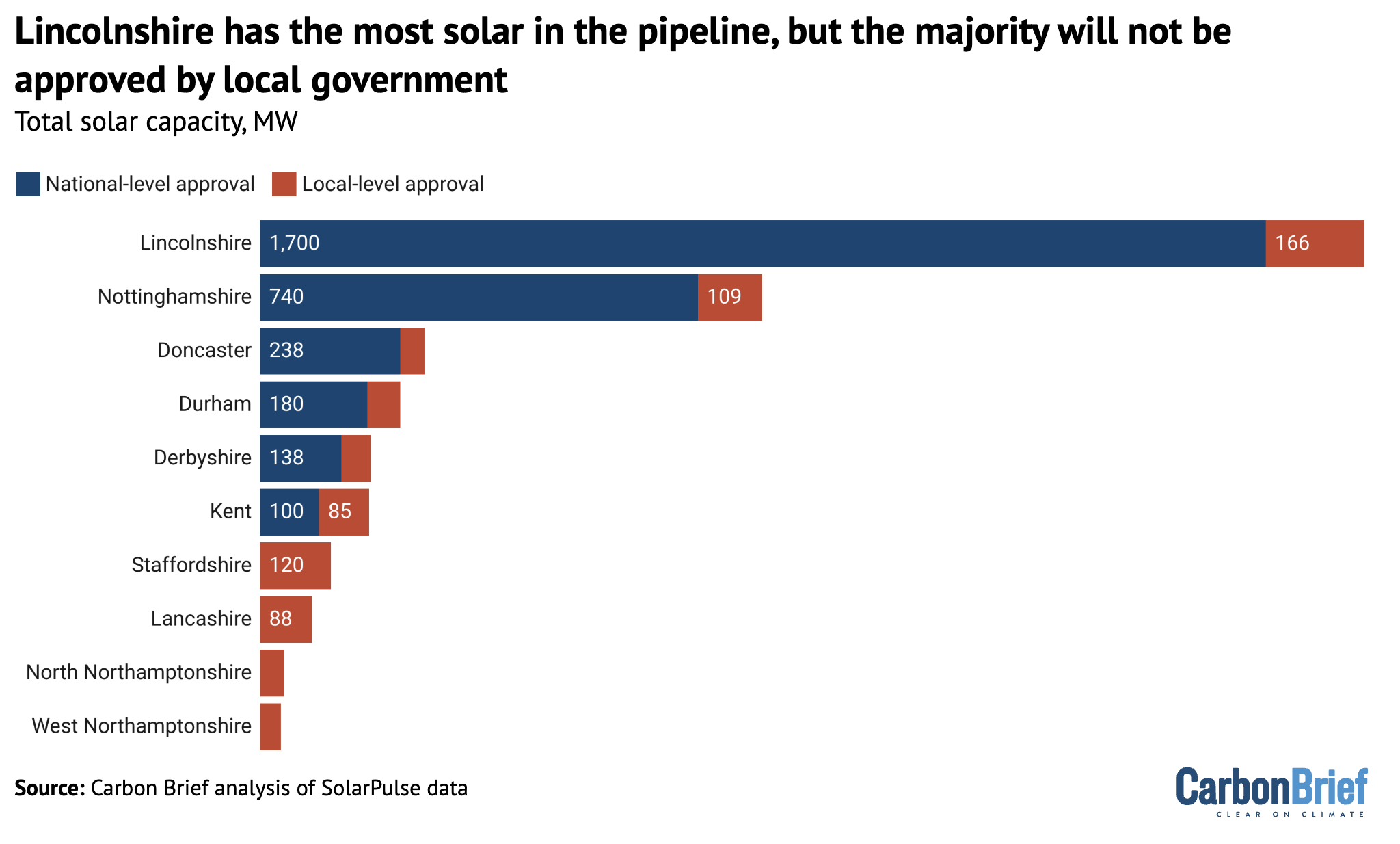

The analysis shows that there is 1,866MW of proposed solar capacity awaiting planning permission in Lincolnshire, by far the largest pipeline, as shown in the chart below.

The majority of this capacity is subject to national-level approval as it is above the NSIP threshold. Nevertheless, the county still has the most solar-power projects awaiting permission from the local planning authority, some 166MW.

(A key reason Lincolnshire dominates this picture for solar power development is due to grid capacity. The county was home to several large-scale coal-fired power plants, such as West Burton, which have shuttered in recent years as part of the UK’s transition away from coal. This means there is more capacity for new generators to connect to the grid in the county than in many others, where the system is currently more constrained.)

Overall, the bulk of the proposed capacity at risk is battery storage, which has seen a surge in applications and installations in recent years.

There was 5,013MW of battery storage capacity in operation as of December 2024 and another 5,115MW under construction, according to trade association RenewableUK. It says an additional 40,223MW had planning approval and a further 77,354MW was under development.

Impact of rejection

Overall, even if local planning authorities under the 10 Reform UK-run councils were to reject all of the nearly 6GW of proposed solar and storage capacity in their areas, it would have a limited impact on the UK’s wider solar, storage and wind targets.

If built, the 786MW of proposed solar would generate 757 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity. On average, a household in the UK uses 2,700 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity each year, meaning these solar farms would be able to power the equivalent of around 280,000 homes – some 1% of the national total.

If all of this proposed solar were rejected and the electricity were generated from gas-fired power stations instead, it would result in an extra 0.3m tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per year. (This is equivalent to less than a tenth of 1% of the UK’s annual total.)

In total, the potential 757GWh of solar power could help displace around £60m of gas per year, based on wholesale prices in 2025 to date.

Private investment could also be impacted. Each 1MW of solar would attract around £1m of investment, meaning the 786MW of capacity would bring roughly £786m into the Reform-led counties. This would have an impact on local supply chains and “community benefit” schemes.

Similarly, battery schemes with four hours of storage capacity also require around £1m of investment per megawatt. This means another £5bn of investment – some 5,076MW of capacity – could be at risk under Reform-led councils.

The total investment at risk for solar and storage is, therefore, close to £6bn.

While a large amount of potential new solar and storage capacity is being proposed in the Reform-led council areas and some could be put at risk as a result, it is also the case that some of these developments could fail for other reasons.

According to research from consultancy Cornwall Insight in February, the current battery storage “connection queue” is double the grid’s requirement for 2030. This means there are many more projects in the queue to gain access to the electricity network than needed.

The government’s plan for reaching its target of “clean power 2030” sets a guideline of 27GW of storage capacity by the end of this decade, whereas some 61GW of battery projects are seeking a grid connection over the same period.

This means the UK would have enough options to meet its 2030 storage requirements even if some proposed battery projects fail due to Reform-led councils, says Ed Porter, global director of industry for battery analysts Modo Energy. He tells Carbon Brief:

“With more than 50GW of battery projects with planning consent, projects could be targeted in Reform areas, but the UK would still have sufficient options to meet clean-power 2030 targets, subject to the achievable build out rate of storage projects.”

The main outcome of Reform-led refusals would be to block profitable projects that could reduce consumer costs and cut CO2 emissions, Porter adds.

Still, there is no guarantee that all of these projects – and the solar proposals – would have received planning permission if Reform UK had not been elected in the relevant areas.

According to figures from Solar Media Market Research, the local authority refusal rate for proposed solar-power projects rose to almost 25% in 2024, the highest on record. This is up from 15% in 2022 and 20% in 2023.

However, the majority of projects that are refused by local authorities still end up being approved. Over the past five years, some 80% of projects that went to appeal were subsequently approved, according to Solar Media. At the time of writing, all 12 of the solar projects that have gone to appeal in 2025 to date have been approved.

Battery energy-storage refusals hit a high of 22% in 2024, according to Solar Media. However, in 2025 so far, this has dropped to 9%.

Connections challenge

Even if Reform UK-led councils are unable to block clean-energy developments outright, the party’s pledge to “fight [developers] every step of the way” could still make the process more challenging.

One key way this could hamper the development of renewable energy technologies is by forcing them to go through the appeals process, extending the time it takes to gain planning permission by as much as a year.

Following changes to the grid connections queue, new connection agreements include strict delivery deadlines for obtaining planning permission.

As such, if a project ends up going to appeal – and is, therefore, delayed – it could risk missing deadlines and having its grid connection agreement terminated.

Additionally, with the capacity limit for NSIPs set to change in December, more projects – solar projects between 50MW and 100MW – will go to local planning authorities for approval. This will increase the number that could be threatened by Reform UK’s influence.

Ultimately, though, there is limited renewable-energy capacity seeking planning permission in Reform-controlled counties, more than enough capacity in planning nationally to meet targets, plus the role of the council in what is – or is not – approved is limited.

Planning lawyer Philips concludes that Reform-led councils are only likely to cause a “nuisance”, with “limited effect”. He says:

“In summary, there is the potential for Reform-led county councils to cause a nuisance for renewable energy projects in the planning process, but this will be limited in effect.

“I’m not concerned about this because of the weight of policy support there is for those projects, which should serve to mitigate the influence Reform could otherwise have.”