Analysis: Will China build hundreds of new coal plants in the 2020s?

Guest authors

03.24.20

Guest authors

24.03.2020 | 8:00amChina’s 14th five-year plan (FYP), setting out its national goals for 2021-2025, will arguably be one of the world’s most important documents for global efforts to tackle climate change.

The overarching plan for economic and social development in the world’s largest emitter is to be finalised and approved in early 2021, followed by more detailed sectoral targets over the next year. A power sector plan can be expected around winter 2021-22.

Ahead of the FYP’s publication, powerful stakeholders, such as the network operator State Grid and industry body the China Electricity Council, are lobbying for targets that would allow hundreds of new coal-fired power stations to be built. And a recent update to the “traffic light system” for new coal-power construction signaled further relaxation of permitting.

This is all despite significant overcapacity in the sector, with more than half of coal-power firms already loss-making and with typical plants running at less than 50% of their capacity.

The push for more coal power also appears at odds with China’s climate goals, including a target to peak its CO2 emissions no later than 2030. To reach this goal, low-carbon sources will need to cover any increases in energy demand, meaning less need for additional electricity generation from coal.

As the country grapples with the coronavirus pandemic, however, controls on overcapacity may be vulnerable to the political priority of propping up economic growth. As a result, the restraints on another coal power boom are likely to be financial and economic, rather than regulatory.

Coal power

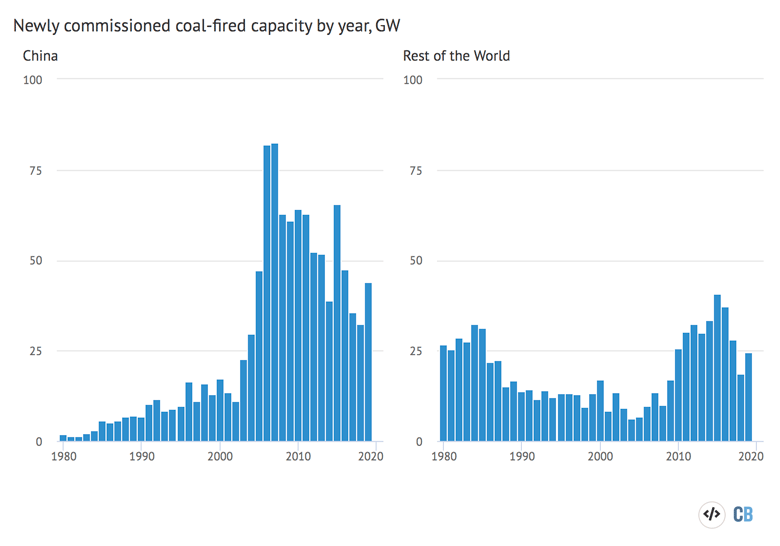

China’s “economic miracle” has seen the country become the world’s second-largest economy and pulled nearly a billion people out of poverty. But this progress has been built on a boom in energy from coal, meaning China has also become the world’s largest carbon polluter by far.

China’s CO2 emissions increased again by around 2% in 2019, based on recently released official economic data, and 65% of the annual growth in energy consumption came from fossil fuels.

Coal is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel and still accounted for 57.7% of China’s energy use in 2019, the data shows. Coal plants, which burn approximately 54% of all coal used in the country, provide 52% of generating capacity and 66% of electricity output – down from a peak of 81% in 2007.

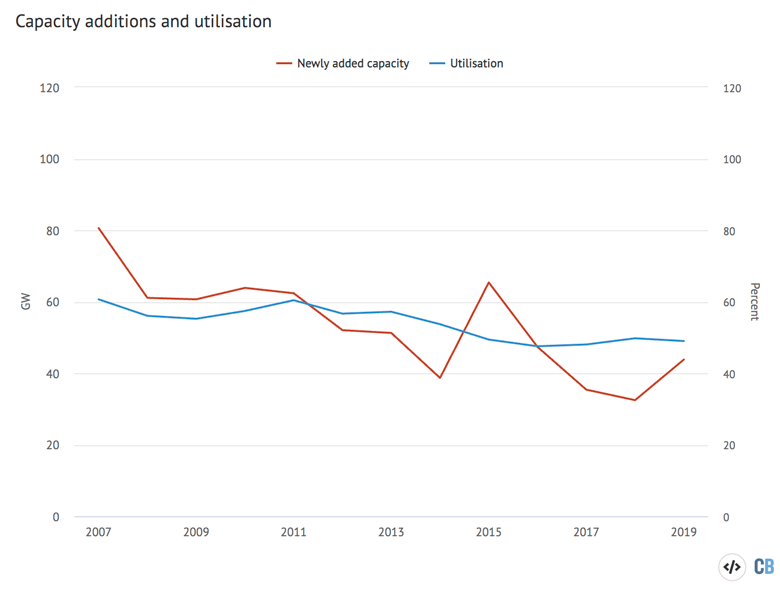

Coal-fired power capacity grew by around 40 gigawatts (GW) in 2019, a 4% increase, and a pick-up from the past two years (the red line on the figure, below). As a result, the coal fleet’s average utilisation rate fell further, to below 50% on average (blue line).

Against this backdrop, there is already heated debate – as outlined below – over China’s 14th FYP, which will set national targets and priorities for the next five years. The energy targets that will be set by the plan mean it will be a crucial document for global efforts to tackle climate change.

Under the existing 13th FYP, coal power capacity is capped at 1,100GW. Separate targets aim to raise the share of China’s energy mix that comes from non-fossil sources to 15% by 2020. More detailed development plans set out indicative targets for sectors such as renewable energy. (Solar has significantly exceeded the relatively low indicative target it was set five years ago.)

Targets of a similar nature are likely to be set as part of the overarching 14th FYP, due to be agreed early next year. Further details will then be set out in sectoral plans over the following year. The power-sector plan, which could include targets for the growth of most generation options – but particularly renewables – might be expected during winter 2021-22, based on previous cycles.

The stakeholder consultancy, scoping and drafting for the power-sector plan has already been started within the government system, with different academic organisations and thinktanks tasked with producing research to support the process.

Roots of overcapacity

China’s coal-power overcapacity dates back to the 12th FYP. This was formulated in the early 2010s as part of the largest economic stimulus programme in history, launched in response to the global financial crisis. It targeted a huge expansion in coal mining and coal-fired power generation.

Then, from 2014, the authority to approve new coal-fired power plants was transferred from the central government to the provincial level, in a drive to cut red tape.

Many local governments jumped at the opportunity to prop up GDP and create demand for locally mined coal with new power projects, leading to around 210 projects with a total capacity of 169GW being rubber-stamped in less than a year.

This surge of new projects came as demand for coal-fired electricity declined from 2013-2015, apparently catching the central government by surprise. It then moved to curtail approvals and suspend already permitted projects.

China’s economic system is based on abundant and cheap capital being made available to the state-owned sector with little concern for economic viability, as long as the investments made are broadly aligned with the five-year plans.

This system can mobilise vast amounts of resources, but is prone to over-investment, as companies and local governments use capacity expansion to boost GDP and gain market share. The planning machinery limits overcapacity with control policies – with varying levels of success.

Signs of stimulus

Many experts and industry bodies argue for a move away from top-down targets and controls, to investment driven by market forces. However, the spending needed to fuel a new stimulus program can only be mobilized if investment is directed at the behest of the state, rather than the market – as a rule, China does not fund stimulus with on-budget spending, but by directing state-owned enterprises and commercial banks to spend more. In these circumstances, lack of controls on capacity additions runs a high risk of over-investment.

For example, efforts to control overcapacity might be vulnerable to the political priority of boosting investment spending to reach economic targets. An indication of this was the loosening of “traffic lights” for new coal-plant approvals, published by the National Energy Administration in February.

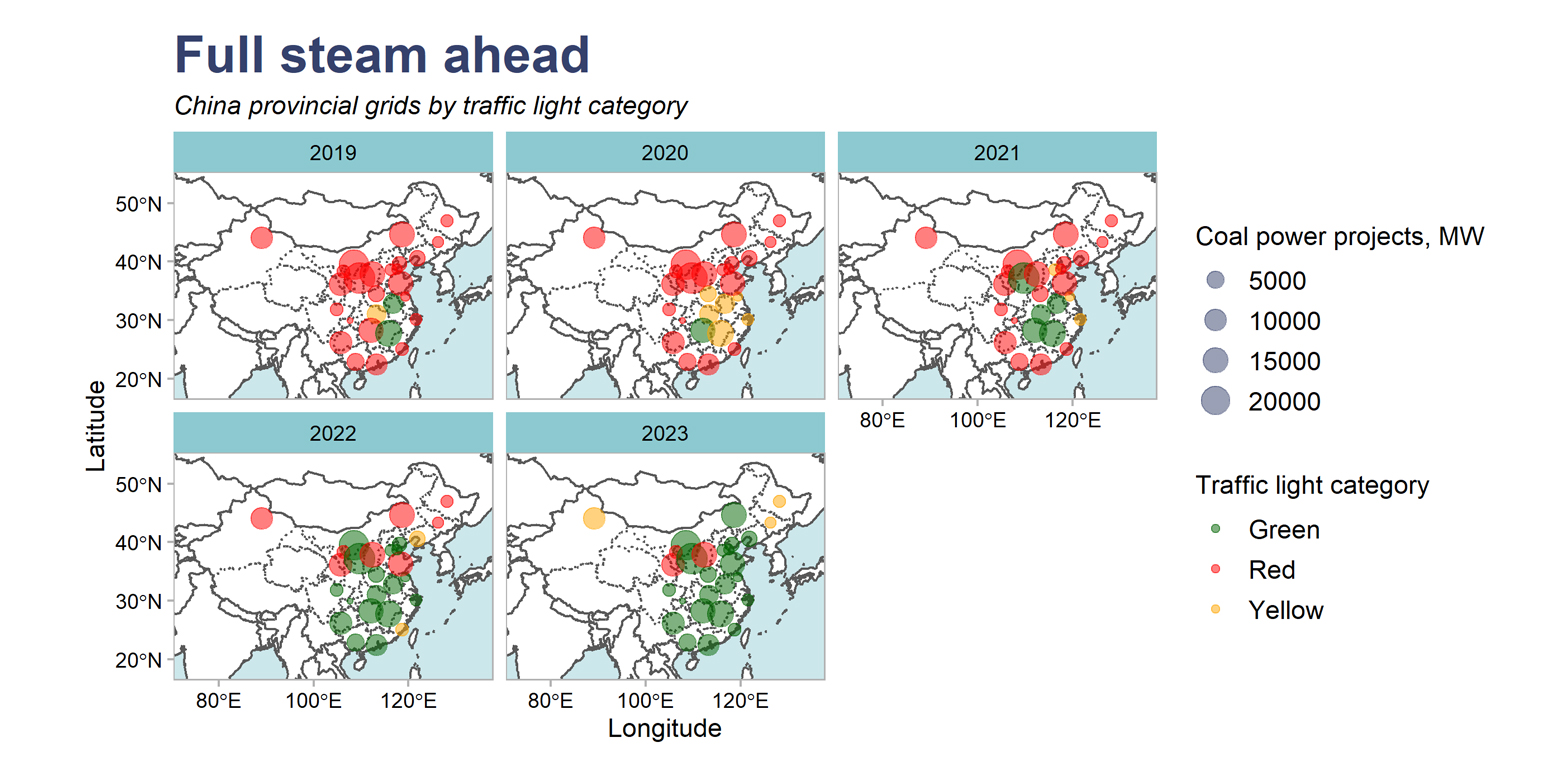

The traffic light policy was first introduced in January 2017 to prevent provinces with overcapacity from permitting new projects. A year ago, however, 21 of China’s 31 provincial grids included in the policy were given a “green light”. Last month this increased to 25, as the figure below shows.

The change is significant, as the four additional greenlighted grid regions have a total of 34GW of coal-fired capacity in the pipeline.

According to data from Global Energy Monitor, the traffic light loosening is already apparent in new project activity in 2019, with construction started or restarted on another 18GW of capacity, while 37GW of previously inactive projects have been revived.

Furthermore, the past weeks have seen the announcement of major infrastructure programmes and other stimulus to offset the economic impacts from the coronavirus, but so far no mention of initiatives prioritising clean energy or other green investment.

The focus on stimulating the economy with major investment – and a recent shift of emphasis towards energy security (below) – appear to cast aside concerns about overcapacity and financial viability.

Some have interpreted Chinese premier Li Keqiang’s remarks at an October 2019 event as a signal of support for coal-power expansion. At the conference a “new energy security strategy” was formulated, in which the core role of coal was emphasised more strongly than renewable energy.

This was widely interpreted as a retreat to coal in the face of energy security concerns, following the trade war with the US. However, China’s energy security fears mainly relate to oil – and, to a lesser degree, gas.

In contrast, the choice between renewables and coal in the power sector is largely a competition between domestic resources. There could be many reasons for China to lower its ambition for renewables, but concerns over dependence on foreign energy would not be among them.

Target fight

Whether or not there is high-level political support for the idea, important industry players are making a push for significantly increased limits on coal-fired power capacity.

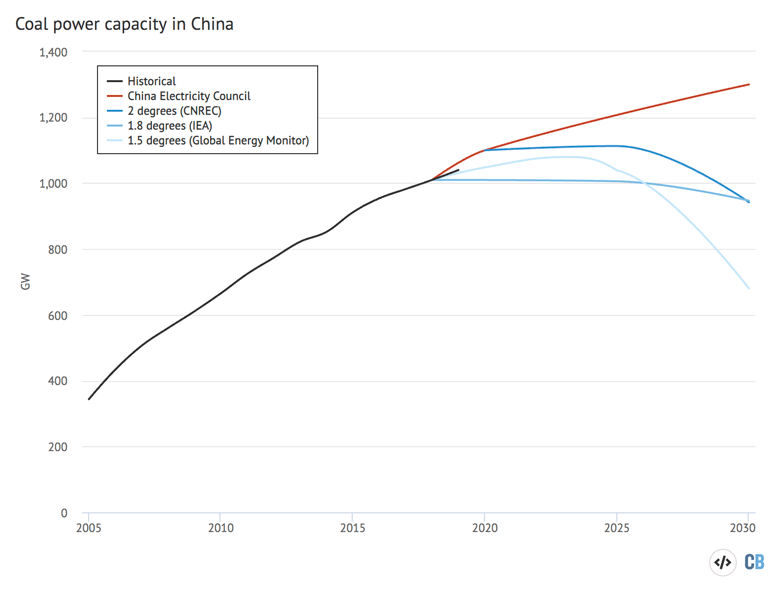

The industry group for China’s power sector giants, China Electricity Council, has argued that coal-power capacity “will” reach 1,300GW by 2030, up from 1,050GW today. This target is based on its projections for annual electricity demand and the need for capacity to meet peak loads.

A cap of 1,300GW in 2030 would imply the addition of well over 300GW of new coal-fired capacity this decade, after accounting for the retirement of older plants.

China Electric Power Planning and Engineering Institute (EPPEI), the authoritative consultancy that has designed most of China’s coal power units and grid infrastructure, warned in June 2019 that 16 provinces in the country should increase new capacity and start working on a new batch of thermal power plants to avoid the possibility of shortages in the next two to three years.

The thinktank affiliated with China’s giant grid utility company, State Grid Corporation of China (SGCC), stressed the need to maintain coal-power capacity in a July 2019 intervention:

“[China] should not close coal power plants at a large scale too soon or too fast and, by around 2030, we should maintain around 1,200GW of coal power to ensure the reliability of the power system, and key power generating regions should retain some backup and reserve capacity.”

However, the thinktank did not clearly define what “too soon” or “too fast” would mean in practice.

Heated debate

One driver of higher capacity targets is the expected electrification of building heat and industrial energy needs, which are often currently supplied by highly polluting small-scale coal-burning. This point has been emphasised by the chief director of the National Energy Administration (NEA).

Replacing direct coal use with gas and electricity has been an important pattern in recent years, in part due to efforts to tackle local air pollution. Energy security concerns are likely to mean further emphasis on electricity rather than gas as the substitute.

However, there is some disagreement over whether higher coal-power capacity is really needed. As an example, the vice secretary general of China’s hydro association, Zhang Boting has said the logic cannot be justified given the overcapacity and underutilisation of existing coal plants.

Looking at other countries that have succeeded in peaking and declining their emissions, electricity generation is the sector where emissions-free solutions are most widely and readily available. Hence, this is the sector that would be expected to lead on emissions reductions.

Energy scenarios that aim to align China’s energy choices with the goals of the Paris Agreement universally project major reductions in coal-fired power generation and capacity. Several such scenarios are shown below, along with the trajectory for coal-fired capacity proposed by the CEC.

China’s relatively young coal fleet, with an average age of 14 years, already faces a very short operating life if the climate pathways shown in the chart above are to be met. Adding even more new capacity would shorten these lifetimes further, making emissions reductions less palatable.

Politics versus economics

While the planning machinery appears to lean towards another wave of coal-power expansion, the industry itself seems more cautious, given the current economic and institutional situation.

Moreover, CO2 emissions depend on coal consumption, not the amount of generating capacity. This means that even if there is a surge of new coal-plant construction, there is no guarantee that China’s coal-power CO2 emissions will rise.

China’s coal-fired capacity currently stands at around 1,050GW, so the targets being pushed by some imply a net increase of 150-250GW. At least 100GW of capacity built before 2000 can be expected to retire by 2030, putting the amount of new capacity being proposed at 250-350GW.

There is already 100GW of new coal power under construction, meaning that another 150-250GW of capacity would have to secure permits and financing and go into construction.

Yet even before the economic havoc wreaked by efforts to contain the coronavirus, Beijing was expected to freeze regulated electricity prices for the next year or two, to help the manufacturing industry and other economic sectors, but undermining the profitability of power generation.

Meanwhile, the annual operating hours of coal power are expected to decline further over time, due to competition from renewable energy and severe overcapacity of the whole system.

With coal plants averaging around 4,000 hours of operation per year, less than half of the 8,760 theoretical maximum, the profitability of major power companies is already extremely low. Last year saw the first bankruptcies in the sector, with pressure from wind and solar one of the key factors.

Electricity market reforms, due to be implemented over the next few years, make the profitability of new coal plants even lower and more uncertain, as the power system moves away from guaranteed operating hours and prices.

The need for capacity to meet peak demand will also be substantially reduced when cross-region transmission and flexibility increases, instead of every province building capacity as if it was an island. Many of the proposed capacity targets and projections appear to ignore these changes.

Climate crunch

Chinese energy data published in late February made it clear that clean-energy investment will need to accelerate substantially to meet China’s climate goals. CO2 emissions increased for the third year in a row in 2019, by around 2%, and only 35% of the increase in energy demand was covered by low-carbon sources.

This share will have to reach 100% or more for emissions to peak and decline, especially as the focus on energy security limits the scope for switching from coal to gas and oil.

Taken together, the evidence points to multiple reasons why some of the major state-owned coal power developers are hesitant to commit to new coal. This is fundamentally different from the assumptions of the policymaking bodies and lobby groups mentioned above.

In a recent magazine interview [no longer online, but cached in summary], a researcher within China’s official thinktank, the Energy Research Institute (ERI), argued that new coal-power development should cease and that coal power should be phased out altogether by 2050. This interview appeared on Chinese social media site WeChat only a few hours before it disappeared, exposing the sensitivity of the issue.

Out of the actors concerned about coal overcapacity, one towers over the others in terms of heft: the supervisor of state-owned assets, SASAC. A leaked file on power-industry debt, reported by Reuters, proposed radical reorganisation of the sector to improve its financial performance.

It suggested merging the good and bad assets of various firms, along with closures at power plants totalling dozens of gigawatts of coal capacity. Given its overview of the financial losses and distress already affecting the sector after excessive coal-capacity expansion, SASAC might be expected to resist another surge in coal power underwritten by the same companies.

A new wave of coal power in China would pose clear risks for global efforts to limit climate change and could greatly complicate the country’s own energy transition. Yet even if the 14th five-year plan targets another coal boom, it could end up falling short due to economic and financial constraints.

There is a parallel in the 12th five-year plan. This created major overcapacity in the sector, but still fell far short of the target set for coal-power growth. Such an outcome would, however, create significant uncertainty, both for the domestic power industry and the international community.

-

Analysis: Will China build hundreds of new coal plants in the 2020s?

-

Analysis: How much more coal power will China build in the 2020s?