Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Ayesha Tandon

01.28.26Ayesha Tandon

28.01.2026 | 4:00pmClimate change could lead to half a million more deaths from malaria in Africa over the next 25 years, according to new research.

The study, published in Nature, finds that extreme weather, rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns could result in an additional 123m cases of malaria across Africa – even if current climate pledges are met.

The authors explain that as the climate warms, “disruptive” weather extremes, such as flooding, will worsen across much of Africa, causing widespread interruptions to malaria treatment programmes and damage to housing.

These disruptions will account for 79% of the increased malaria transmission risk and 93% of additional deaths from the disease, according to the study.

The rest of the rise in malaria cases over the next 25 years is due to rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns, which will change the habitable range for the mosquitoes that carry the disease, the paper says.

The majority of new cases will occur in areas already suitable for malaria, rather than in new regions, according to the paper.

The study authors tell Carbon Brief that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

Malaria in a warming world

Malaria kills hundreds of thousands of people every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 610,000 people died due to the disease in 2024.

In 2024, Africa was home to 95% of malaria cases and deaths. Children under the age of five made up three-quarters of all African malaria deaths.

The disease is transmitted to humans by bites from mosquitoes infected with the malaria parasite. The insects thrive in high temperatures of around 29C and need stagnant or slow-moving water in which to lay their eggs. As such, the areas where malaria can be transmitted are heavily dependent on the climate.

There is a wide body of research exploring the links between climate change and malaria transmission. Studies routinely find that as temperatures rise and rainfall patterns shift, the area of suitable land for malaria transmission is expanding across much of the world.

Study authors Prof Peter Gething and Prof Tasmin Symons are researchers at the Curtin University’s school of population health and the Malaria Atlas Project from the The Kids Research Institute, Australia.

They tell Carbon Brief that this approach does not capture the full picture, arguing that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The paper notes that extreme weather events are regularly linked to surges in malaria cases across Africa and Asia. This is, in-part, because storms, heavy rainfall and floods leave pools of standing water where mosquitoes can breed. For example, nearly 15,000 cases of malaria were reported in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai hitting Mozambique in 2019.

However, the study authors also note that weather extremes often cause widespread disruption, which can limit access to healthcare, damage housing or disrupt preventative measures such as mosquito nets. These factors can all increase vulnerability to malaria, driving the spread of the disease.

In their study, the authors assess both the “ecological” effects of climate change – the impacts of temperature and rainfall changes on mosquito populations – and the “disruptive” effects of extreme weather.

Mosquito habitat

To assess the ecological impacts of climate change, the authors first identify how temperature, rainfall and humidity affect mosquito lifecycles and habitats.

The authors combine observational data on temperature, humidity and rainfall, collected over 2000-22, with a range of datasets, including mosquito abundance and breeding habitat.

The authors then use malaria infection prevalence data, collected by the Malaria Atlas Project, which describes the levels of infection in children aged between two and 10 years old.

Symons and Gething explain that they can then use “sophisticated mathematical models” to convert infection prevalence data into estimates of malaria cases.

Comparing these datasets gives the authors a baseline, showing how changes in climate have affected the range of mosquitoes and malaria rates across Africa in the early 21st century.

The authors then use global climate models to model future changes over 2024-49 under the SSP2-4.5 emissions pathway – which the authors describe as “broadly consistent with current international pledges on reduced greenhouse gas emissions”.

The authors also ran a “counterfactual” scenario, in which global temperatures do not increase over the next 25 years. By comparing malaria prevalence in their scenarios with and without climate change, the authors could identify how many malaria cases were due to climate change alone.

Overall, the ecological impacts of climate change will result in only a 0.12% increase in malaria cases by the year 2050, relative to present-day levels, according to the paper.

However, the authors say that this “minimal overall change” in Africa’s malaria rates “masks extensive geographical variation”, with some areas seeing a significant increase in malaria rates and others seeing a decrease.

Disruptive extremes

In contrast, the study estimates that 79% of the future increase in malaria transmission will be due to the “disruptive” impacts of more frequent and severe weather extremes.

The authors explain that extreme weather events, such as flooding and cyclones, can cause extensive damage to housing, leaving people without crucial protective equipment such as mosquito nets.

It can also destroy other key infrastructure, such as roads or hospitals, preventing people from accessing healthcare. This means that in the aftermath of an extreme weather event, people face a greater risk of being infected with malaria.

The climate models run by the study authors project an increase in “disruptive” extreme weather events over the next 25 years.

For example, the authors find that by the middle of the century, cyclones forming in the Indian Ocean will become more intense, with fewer category 1 to category 4 events, but more frequent category 5 events. They also find that climate change will drive an increase in flooding across Africa.

The study finds that without mitigation measures, these disruptive events will drive up the risk of malaria – especially in “main river systems” and the “cyclone-prone coastal regions of south-east Africa”.

Between 2024 and 2050, 67% of people in Africa will see their risk of catching malaria increase as a result of climate change, the study estimates.

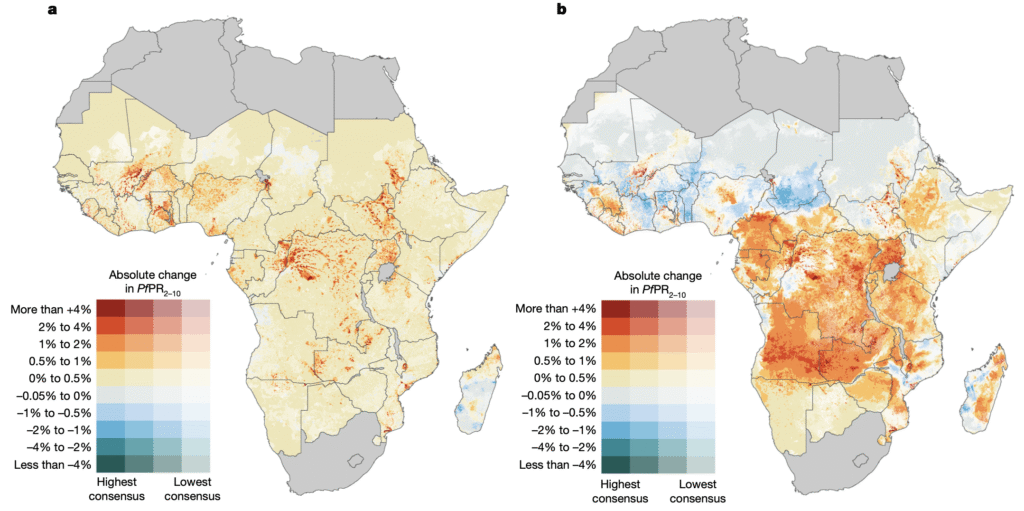

The map below shows the percentage change in malaria transmission rate in the 2040s due to the disruptive impacts of climate change alone (left) and a combination of the disruptive and ecological impacts (right), compared to a scenario in which there is no change in the climate. Red and yellow indicate an increase in malaria risk, while blue indicates a reduction.

Colours in lighter shading indicate lower model confidence, while stronger colours indicate higher model confidence.

The maps show that the “disruptive” effects of climate change have a more uniform effect, driving up malaria risk across the entire continent.

However, there is greater regional variation when these effects are combined with “ecological” drivers.

The authors find that warming will increase malaria risk in regions where the temperature is currently too low for mosquitoes to survive. This includes the belt of lower latitude southern Africa, including Angola, southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, as well as highland areas in Burundi, eastern DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda.

Meanwhile, they find that warming will drive down malaria transmission in the Sahel, as temperatures rise above the optimal range for mosquitoes.

Rising risk

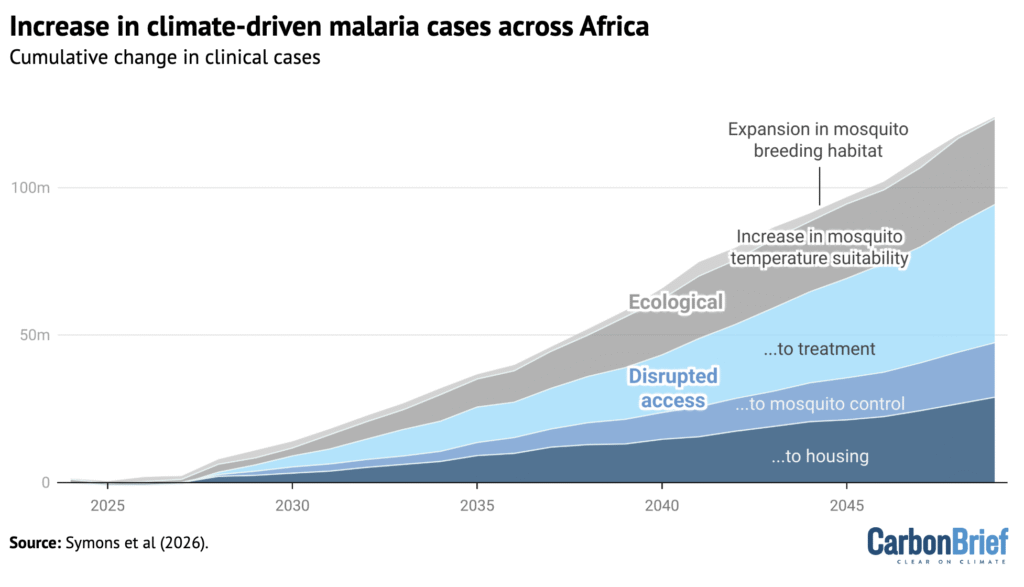

The combined “disruptive” and “ecological” impacts of climate change will drive an additional 123m “clinical cases” of malaria across Africa, even if the current climate pledges are met, the study finds.

This will result in 532,000 additional deaths from malaria over the next 25 years, if the disease’s mortality rate remains the same, the authors warn.

The graph below shows the increase in clinical cases of malaria projected across Africa over the next 25 years, broken down into the different ecological (yellow) and disruptive (purple) drivers of malaria risk.

However, the authors stress that there are many other mechanisms through which climate change could affect malaria transmission – for example, through food insecurity, conflict, economic disruption and climate-driven migration.

“Eradicating malaria in the first half of this century would be one of the greatest accomplishments in human history,” the authors say.

They argue that accomplishing this will require “climate-resilient control strategies”, such as investing in “climate-resilient health and supply-chain infrastructure” and enhancing emergency early warning systems for storms and other extreme weather.

Dr Adugna Woyessa is a senior researcher at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the new paper could help inform national malaria programmes across Africa.

He also suggests that the findings could be used to guide more “local studies that address evidence gaps on the estimates of climate change-attributed malaria”.

Study authors Symons and Gething tell Carbon Brief that during their study, they interviewed “many policymakers and implementers across Africa who are already grappling with what climate-resilient malaria intervention actually looks like in practice”.

These interventions include integrating malaria control into national disaster risk planning, with emergency responses after floods and cyclones, they say. They also stress the need to ensure that community health workers are “well-stocked in advance of severe weather”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

Symons, T. et al (2026). Projected impacts of climate change on malaria in Africa, Nature, doi:10.1038/s41586-025-10015-z