Climate change set to fuel more “monster” El Niños, scientists warn

Roz Pidcock

08.17.15Roz Pidcock

17.08.2015 | 5:00pmThe much-anticipated El Niño gaining strength in the Pacific is shaping up to be one of the biggest on record, scientists say. With a few months still to go before it reaches peak strength, many are speculating it could rival the record-breaking El Niño in 1997/8.

Today, a new review paper in Nature Climate Change suggests we can expect more of the same in future, with rising temperatures set to almost double the frequency of extreme El Niño events.

Supersizing

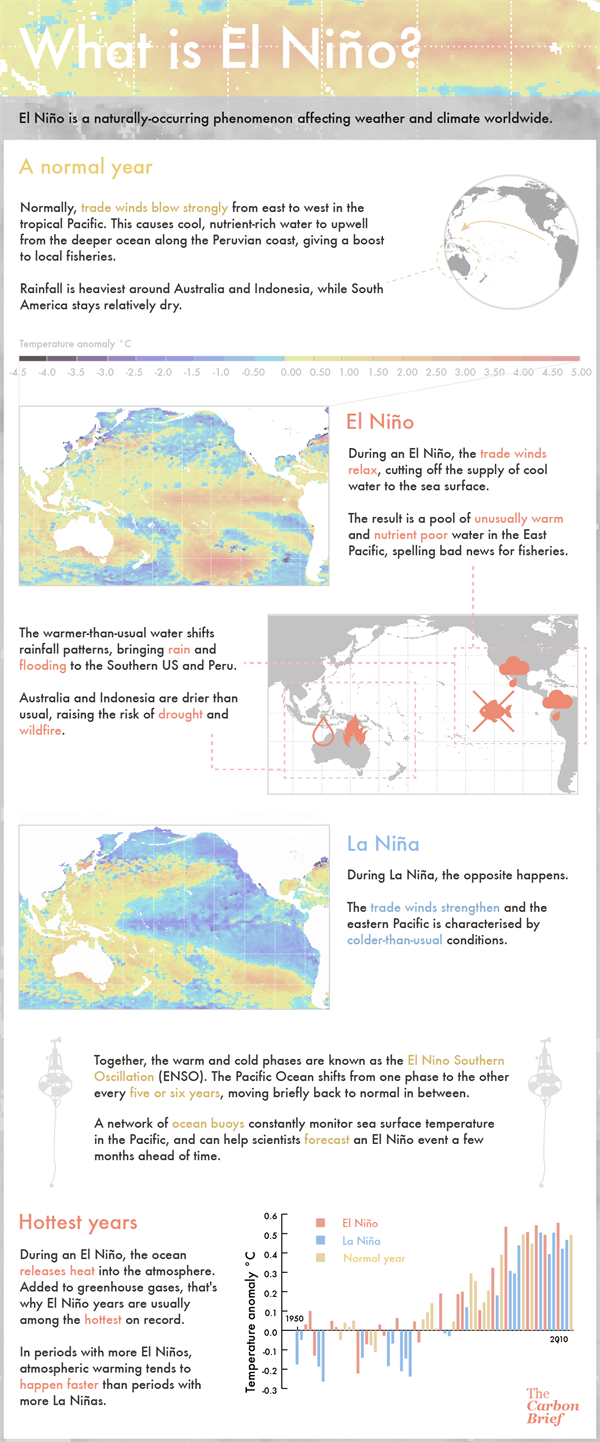

Every five years or so, a change in the winds causes a shift to warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean – known as El Niño.

Together with its cooler counterpart, La Niña, this is known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is responsible for most of the fluctuations in global weather we see from one year to the next.

Last week, US scientists confirmed they expect “a strong El Niño” to peak in the next few months. The event brewing in the Pacific is already “significant and strengthening”, said the statement from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Centre.

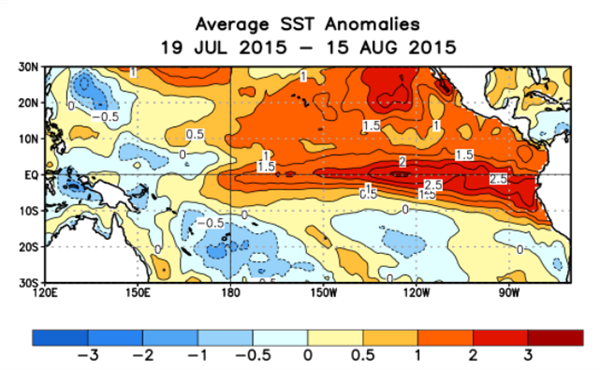

The latest temperature maps, released today, confirm parts of the tropical Pacific are up to 3C warmer than the long term average (dark red in the map below).

Sea surface temperature anomalies in the Tropical Pacific over the last four weeks. Source: Climate Prediction Center/NCEP, NOAA.

A separate comment piece in the same journal explains how scientists have been left scratching their heads over why El Niño has reemerged with such vigour after a false start last year.

An El Niño first looked to be on the way back in Spring 2014, only for it to inexplicably fizzle out, explains the comment piece’s author, Dr Michael McPhaden from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The scientific community was fooled for a second time when El Niño unexpectedly flared up again in 2015, says McPhaden. Calling this behaviour “doubly perplexing”, McPhaden adds:

[T]he much-ballyhooed El Niño, though moribund, was not completely dead. Surprisingly, it came roaring back with renewed vigour during the first half of 2015.

Prof Kim Cobb, co-author on the first of the two articles today and paleoclimate expert at Georgia Institute of Technology, tells Carbon Brief watching El Niño evolve has been “nothing short of thrilling.”

‘Blurry crystal ball’

The quest to understand how El Niño and La Niña work has attracted a lot of scientific interest. But there are other important reasons to study them.

During an El Niño, Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Africa and Northeast Brazil tend to experience drought while Southern California, the southern US East equatorial Africa, western South America and Southeastern South America tend to see flooding, McPhaden tells Carbon Brief. The Atlantic hurricane season tends to quieten down, while the number of Pacific hurricanes and cyclones grows.

El Niño storms in 1998 caused the Rio Nido mud slides in northern California, damaging houses and cars. Credit: Dave Gatley | Wikimedia.

Because of their potentially serious impacts, there is a huge societal pressure to better predict when an El Niño or La Niña event will occur and how strong it will be. But predicting El Niño’s response to climate change isn’t simple, McPhaden tells Carbon Brief:

Our crystal ball is blurry when it comes to how El Niño and its impacts may change in the future.

The new research, which McPhaden was not involved in, reviews all the available scientific evidence on ENSO and climate change, concluding that extreme El Niño events will happen more often as the climate warms.

If emissions stay very high, the authors expect extreme El Niño events with impacts similar to the one in 1997/8 will almost double in frequency by the end of the century, from about once every 28 years today to once every 16 years.

As the climate warms, the scientists also expect to see an increase in extreme La Niña events. As the authors say in the paper:

ENSO-related catastrophic weather events are thus likely to occur more frequently with unabated greenhouse-gas emissions.

Soul searching

How El Niño and La Niña events might change in response to climate change is one of the most compelling questions in today’s climate research today, says McPhaden in his comment piece.

On much shorter timescales, what caused last year’s El Niño to fizzle out only to re-emerge with such force is equally fascinating. Why forecasts and expectations fell so wide of the mark has led to a fair amount of soul searching among scientists, says McPhaden.

Many El Niño experts were fooled by these developments, both when the widely anticipated monster El Niño went into steep decline and again when it re-ignited with such startling intensity.

One thing El Niño scientists have probably learned is not to take anything for granted. McPhaden concludes:

We’ve learned a lot but it continues to surprise us. Nature has a way of humbling you when you assume you know more than you do.

Main image: November 2006 flood, Granite Falls on the Stillaguamish River, Washington. Credit: Walter Siegmund/Wikimedia Commons.

-

Climate change set to fuel more "monster" El Niños, scientists warn

-

The much-anticipated El Niño gaining strength in the Pacific is shaping up to be one of the biggest on record.