Explainer: Why gas plays a minimal role in China’s climate strategy

Karen Teo

01.22.26

Karen Teo

22.01.2026 | 8:00amTen years ago, switching from burning coal to gas was a key element of China’s policy to reduce severe air pollution.

However, while gas is seen in some countries as a “bridging” fuel to move away from coal use, rapid electrification, uncompetitiveness and supply concerns have suppressed its share in China’s energy mix.

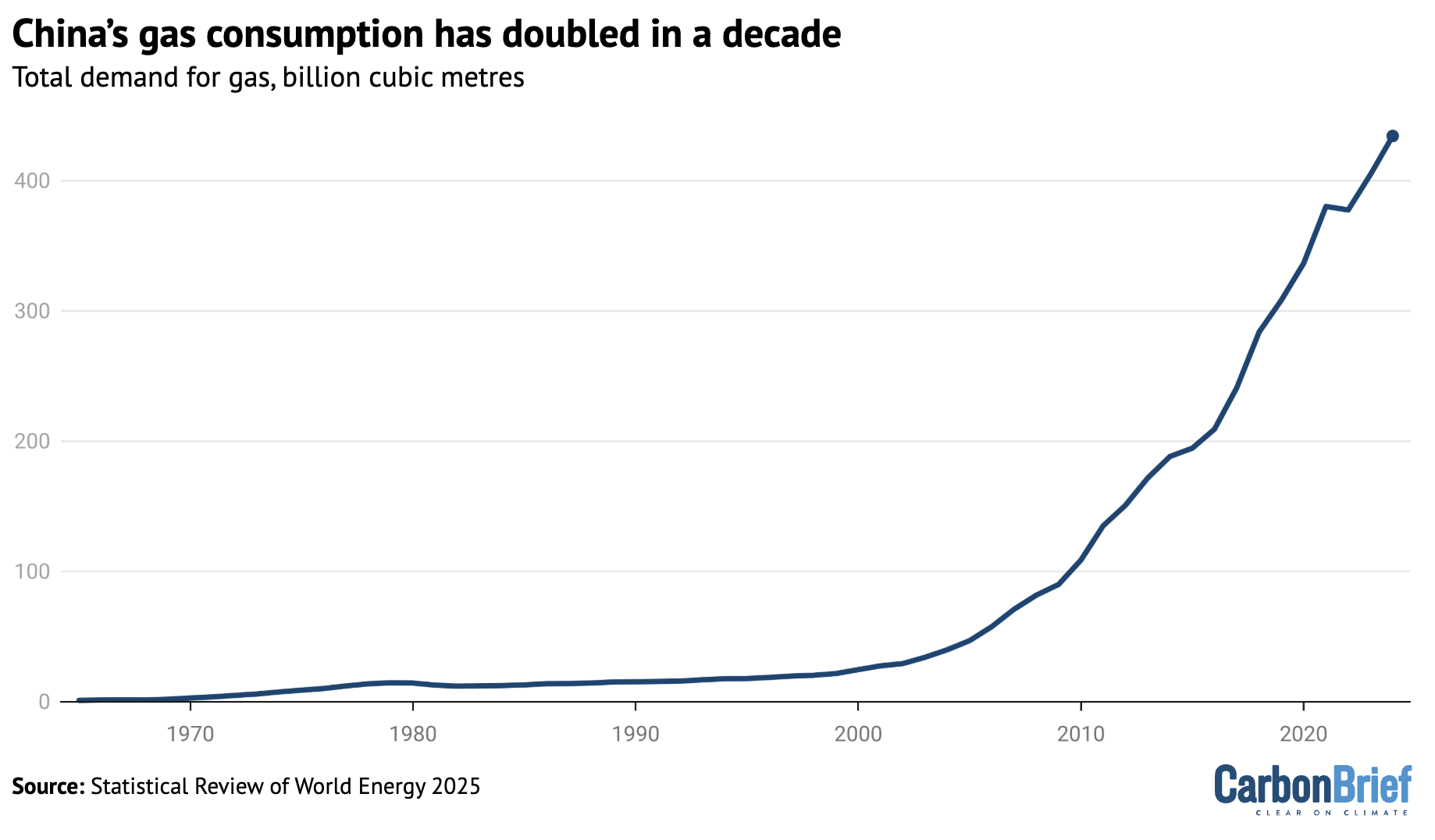

As such, while China’s gas demand has more than doubled over the past decade, the fuel is not currently playing a decisive role in the country’s strategy to tackle climate change.

Instead, renewables are now the leading replacement for coal demand in China, with growth in solar and wind generation largely keeping emissions growth from China’s power sector flat.

While gas could play a role in decarbonising some aspects of China’s energy demand – particularly in terms of meeting power demand peaks and fuelling heavy industry – multiple factors would need to change to make it a more attractive alternative.

Small, but impactful

The share of gas in China’s primary energy demand is small and has remained relatively unchanged at around 8-9% over the past five years.

It also comprises 7% of China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fuel combustion, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Gas combustion in China added 755m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) into the atmosphere in 2023 – double the total amount of CO2 emitted by the UK.

However, its emissions profile in China lags well behind that of coal, which represented 79% of China’s fuel-linked CO2 emissions and was responsible for almost 9bn tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2023, according to the same IEA data.

Gas consumption continues to grow in line with an overall uptick in total energy demand. Chinese gas demand, driven by industry use, grew by around 7-8% year-on-year in 2024, according to different estimates.

This rapid growth is, nevertheless, slightly below the 9% average annual rise in China’s gas demand over the past decade, during which consumption has more than doubled overall, as shown in the figure below.

The state-run oil and gas company China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) forecast in 2025 that demand growth for the year may slow further to just over 6%.

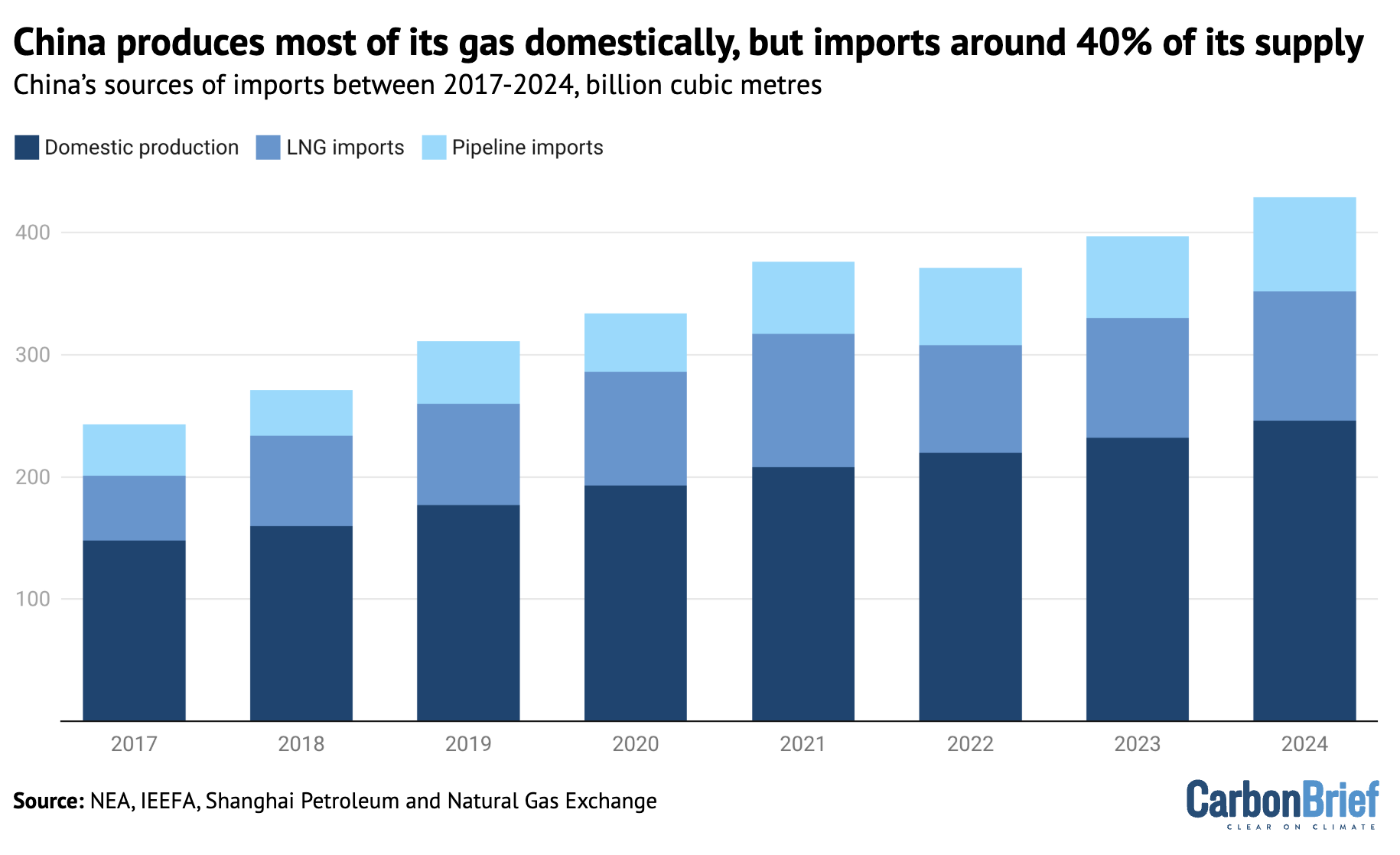

The majority of China’s gas demand in 2023 was met by domestic gas supply, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Most of this supply comes from conventional gas sources. But incremental Chinese domestic gas supply in recent years has come from harder-to-extract unconventional sources, including shale gas, which accounted for as much as 45% of gas production in 2024.

Despite China’s large recoverable shale-gas resources and subsidies to encourage production, geographical and technical limitations have capped production levels relative to the US, which is the world’s largest gas producer by far.

CNPC estimates Chinese gas output will grow by just 4% in 2025, compared with 6% growth in 2024. Nevertheless, output is still expected to exceed the 230bn cubic metre national target for 2025.

Liquified natural gas (LNG) is China’s second most-common source of gas, imported via giant super-cooled tankers from countries including Australia, Qatar, Malaysia and Russia.

This is followed by pipeline imports – which are seen as cheaper, but less reliable – from Russia and central Asia.

One particularly high-profile pipeline project is the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline project. However, Beijing has yet to explicitly agree to investing in or purchasing the gas delivered by the project. Disagreements around pricing and logistics have hindered progress.

Evolving role

Beijing initially aimed for gas to displace coal as part of a broader policy to tackle air pollution.

A three-year action plan from 2018-2020, dubbed the “blue-sky campaign”, helped to accelerate gas use in the industrial and residential sectors, as gas displaced consumption of “dispersed coal” (散煤)”– referring to improperly processed coal that emits more pollutants.

Meanwhile, several cities across northern and central China were also mandated to curtail coal usage and switch to gas instead. Many of these cities were based in provinces with a strong coal mining economy or higher winter heating demand.

China’s pollution levels saw “drastic improvement” as a result, according to a report by research institute the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

(In January 2026, there were widespread media reports of households choosing not to use gas heating despite freezing temperatures, as a result of high prices following the expiry of subsidies for gas use.)

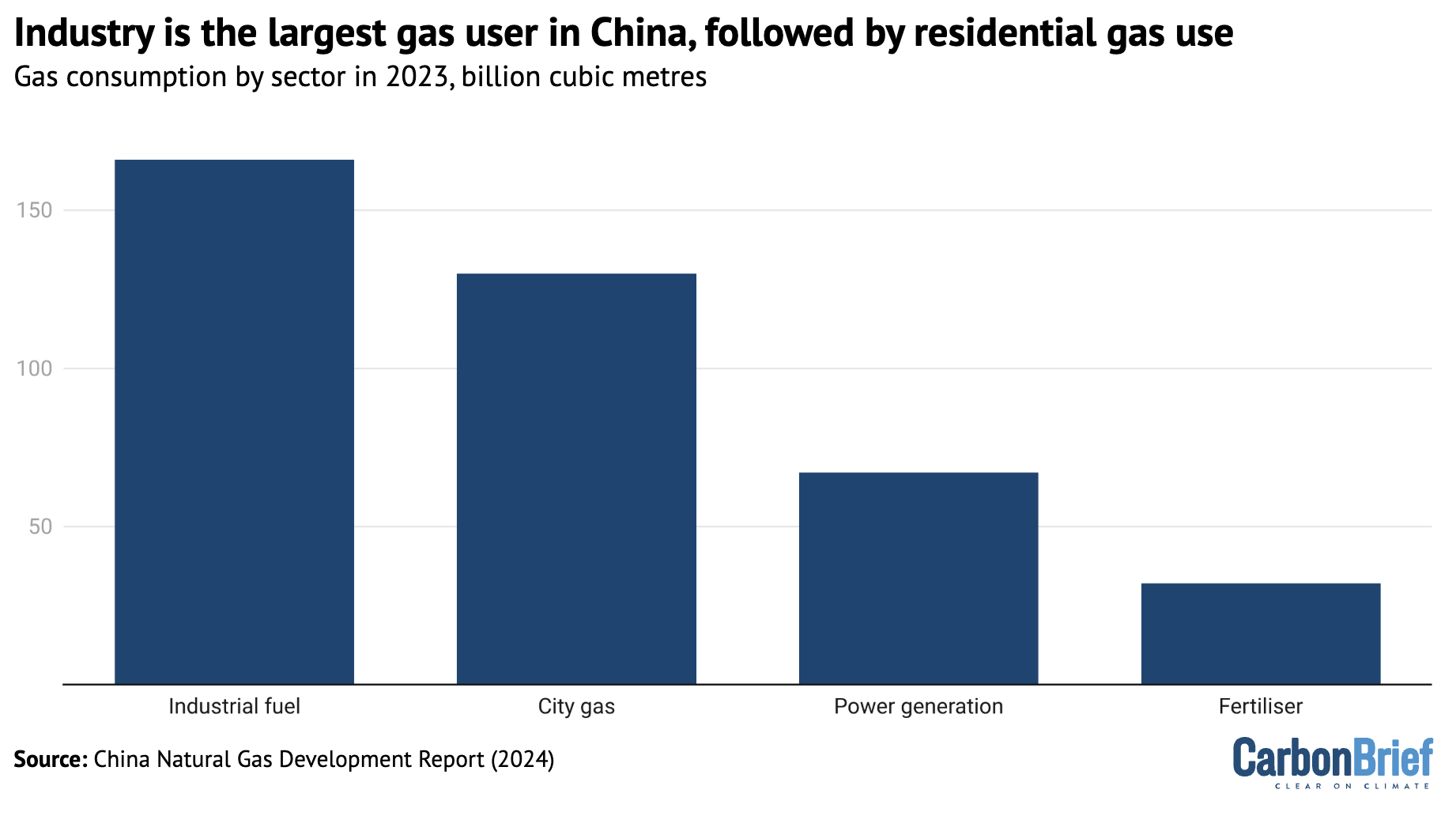

Industry remains the largest gas user in China, with “city gas” – gas delivered by pipeline to urban areas – trailing in second, as shown in the figure below. Power generation is a distant third.

Gas has never gained momentum in China’s power sector, with its share of power generation remaining at 4% while wind and solar power’s share has soared from 4% to 22% over the past decade, Yu Aiqun, a research analyst at the US-based thinktank Global Energy Monitor, tells Carbon Brief.

Yu adds that this stagnation is largely due to insufficient and unreliable gas supply, which drives up prices and makes gas less competitive compared to coal and renewables. She says:

“With the rapid expansion of renewables and ongoing geopolitical uncertainties, I don’t foresee a bright future for gas power.”

Average on-grid gas-fired power prices of 0.56-0.58 yuan per kilowatt hour (yuan/kWh) in China are far higher than that of around 0.3-0.4 yuan/kWh for coal power, according to some industry estimates. Recent auction prices for renewables are even cheaper than this.

Meanwhile, the share of renewables in China’s power capacity stood at 55% in 2024, compared with gas at around 4%.

Generation from wind and solar in particular has increased by more than 1,250 terawatt-hours (TWh) in China since 2015, while gas-fired generation has increased by just 140TWh, according to IEEFA.

As the share of coal has shrunk from 70% to 61% during this period, IEEFA suggests that renewables – rather than gas – are displacing coal’s share in the generation mix.

However, China’s gas capacity may still rise from approximately 150 gigawatts (GW) in 2025 to 200GW by 2030, Bloomberg reports.

A report by the National Energy Administration (NEA) on development of the sector notes that gas will continue to play a “critical role” in “peak shaving”, where gas turbines can be used for short periods to meet daily spikes in demand. As such, the NEA says gas will be an “important pillar” in China’s energy transition.

In 2024, a new policy on gas utilisation also “explicitly promoted” the use of gas peak-shaving power plants, according to industry outlet MySteel.

China’s current gas storage capacity is “insufficient”, according to CNPC, reducing its ability to meet peak-shaving demand. The country built 38 underground gas storage sites with peak-shaving capacity of 26.7bn cubic metres in 2024, but this accounts for just 6% of its annual gas demand.

Transport use

Gas is instead playing a bigger part in the displacement of diesel in the transport sector, due to the higher cost competitiveness of LNG as a fuel – particularly in the trucking sector.

CNPC expects that LNG displaced around 28-30m tonnes of diesel in the trucking sector in 2025, accounting for 15% of total diesel demand in China.

This is further aided by policy support from Beijing’s equipment trade-in programme, part of efforts to stimulate the economy.

However, gas is not necessarily a better option for heavy-duty, long-haul transportation, due to poorer fuel efficiency compared with electric vehicles (EVs).

In fact, “new-energy vehicles” (NEVs) – including hydrogen fuel-cell, pure-electric and hybrid-electric trucks – are displacing both LNG-fueled trucks and diesel heavy-duty vehicles (HDVs).

In the first half of 2025, battery-electric models accounted for 22% of all HDV sales, a year-on-year increase of 9%, while market share for LNG-fueled trucks fell from 30% in 2024 to 26%.

Gas can be cheaper than oil but is not competitive with EVs and – with the emergence of zero-emission fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia – gas may eventually lose even this niche market, says Yu.

Supply security

Chinese government officials frequently note that China is “rich in coal, poor in oil and short of gas” (“富煤贫油少气”). Concerns around import dependence have underpinned China’s focus on coal as a source of energy security.

However, Beijing increasingly sees electrification as a more strategic way to decarbonise its transport sector, according to some analysts.

“Overall, electrification is a clear energy security strategy to reduce exposure to global fossil fuel markets,” says Michal Meidan, head of the China energy research programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Chinese oil and gas production grew dramatically in the last few years under a seven-year action plan from 2019-25, as Beijing ordered its state oil firms to ramp up output to ensure energy security.

Despite this, gas import dependency still hovers at around 40% of demand. This, according to assessments in government documents, exposes the country to price shocks and geopolitical risks.

The graph below shows the share of domestically produced gas (dark blue), LNG imports (mid-blue) and pipeline imports (light blue), in China’s overall gas supply between 2017 and 2024.

“Gas use is unlikely to play a significant role in decarbonising the power system, but could be more significant in industrial decarbonisation,” Meidan tells Carbon Brief.

She estimates that if LNG prices fall to $6 per million British thermal units (btu), compared to an average of $11 in 2024-25, this could encourage fuel switching in the steel, chemical manufacturing, textiles, ceramics and food processing industries.

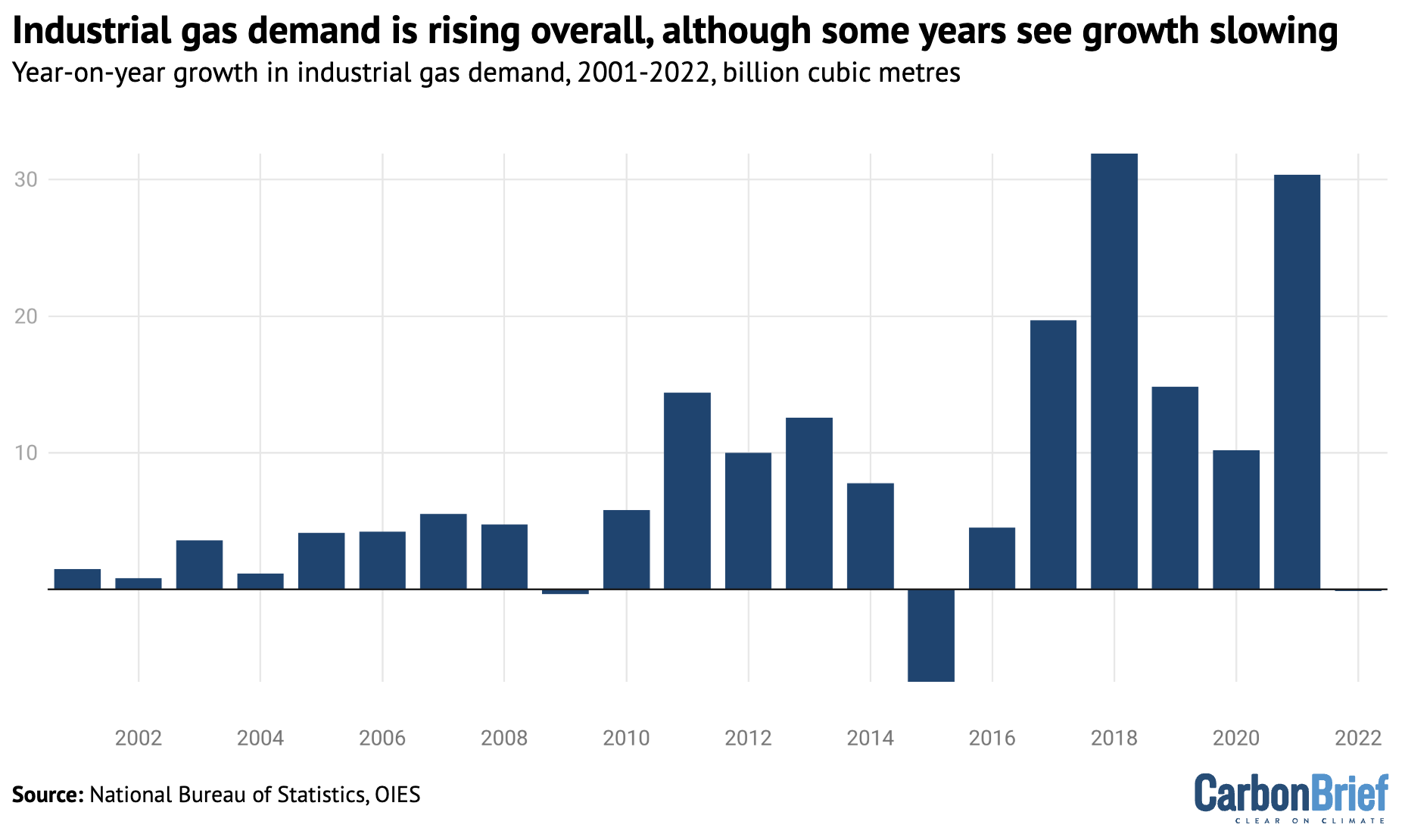

The chart below shows the year-on-year change in gas demand between 2001-2022.

Growth in gas demand has been decelerating in some industries in recent years, such as refining. But it also remains unclear if Beijing will adopt more aggressive policies favouring gas, Meidan adds.

A roadmap developed by the Energy Research Institute (ERI), a thinktank under the National Development and Reform Commission’s Academy of Macroeconomic Research, finds that gas only begins to play an equivalent or greater role in China’s energy mix than coal by 2050 at the earliest – 10 years ahead of China’s target for achieving carbon neutrality.

Both fossil fuels play a significantly smaller role than clean-energy sources at this point.

Wang Zhongying and Kaare Sandholt, both experts at the ERI, write in Carbon Brief:

“Gas does not play a significant role in the power sector in our scenarios, as solar and wind can provide cheaper electricity while existing coal power plants – together with scaled-up expansion of energy storage and demand-side response facilities – can provide sufficient flexibility and peak-load capacity.”

Ultimately, China’s push for gas will be contingent on its own development goals. Its next five-year plan, from 2026-2030, will build a framework for China’s shift to controlling absolute carbon emissions, rather than carbon intensity.

Recent recommendations by top Chinese policymakers on priorities for the next five-year plan did not explicitly mention gas. Instead, the government endorses “raising the level of electrification in end-use energy consumption” while also “promoting peaking of coal and oil consumption”.

The Chinese government feels that gas is “nice to have…if available and cost-competitive but is not the only avenue for China’s energy transition,” says Meidan.