Factcheck: How the UK is – and is not – studying solar geoengineering

Daisy Dunne

05.15.25Daisy Dunne

15.05.2025 | 12:18pmThe UK government’s “high-risk” research funding agency last week announced that it will invest £57m ($76m) in a new solar geoengineering research programme.

“Solar geoengineering” refers to methods that aim to address some of the impacts of a warming climate by reflecting away more sunlight from the Earth.

The programme, spearheaded by the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria), will fund 21 projects globally.

This includes small-scale outdoor experiments, involving attempts to thicken Arctic sea ice and brighten clouds above Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to reflect away sunlight.

The news was reported breathlessly by the UK media, with some outlets conjuring images of the government one day “dimming the sun” or trying to modify the weather and others focusing on the “secretive” nature of Aria and its research.

The reaction was even more exaggerated on social media, where anonymous accounts seized upon the news to spread misinformation about existing “secret” government schemes to “control” the weather.

At the same time, the programme – first reported last year – has sparked legitimate debate among climate scientists, who have long held diverging views on whether more research funding should be channelled into solar geoengineering.

Below, Carbon Brief explains what the new solar geoengineering research programme consists of and explores the social and ethical concerns surrounding the technology.

- What is the UK’s new solar geoengineering research programme?

- How does this compare to past solar geoengineering efforts in the UK and globally?

- Why do some scientists say solar geoengineering research is needed?

- Why are there social and ethical concerns around solar geoengineering?

What is the UK’s new solar geoengineering research programme?

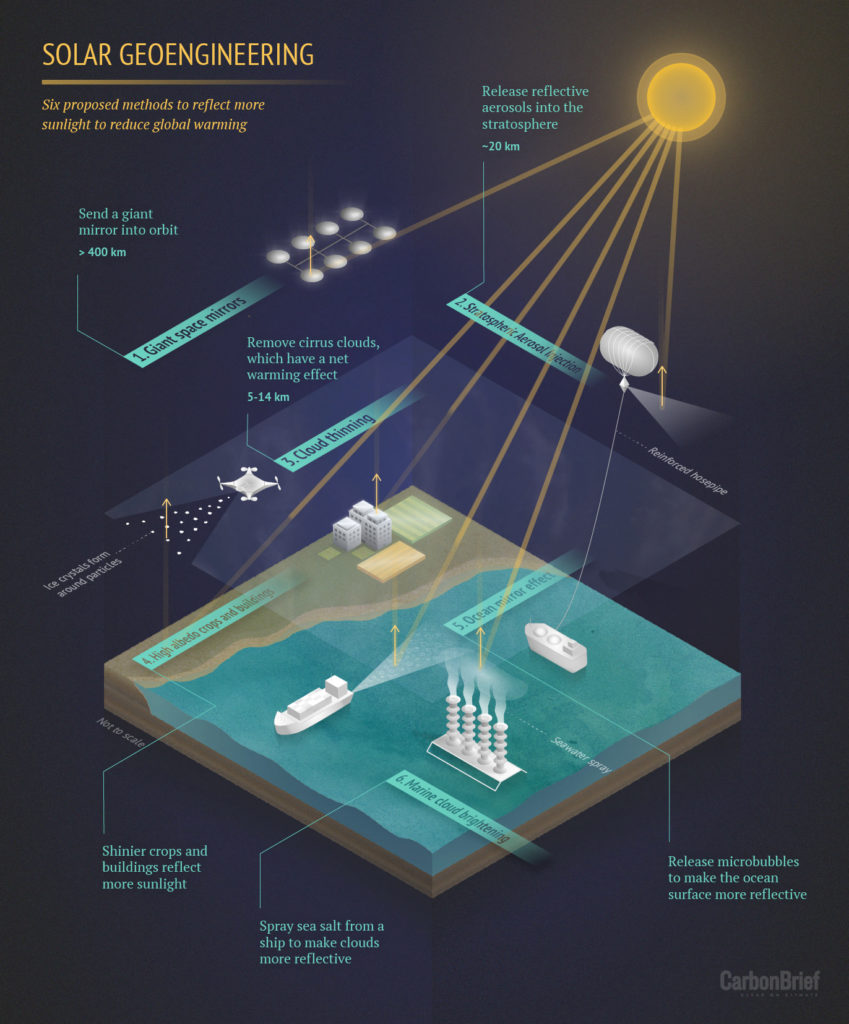

Solar geoengineering is a term used to describe a group of hypothetical technologies that could, in theory, counteract temperature rise by reflecting more sunlight away from the Earth’s surface. (It is also sometimes called “solar radiation modification”.)

The most commonly proposed idea is to introduce reflective aerosols high up into the stratosphere, which would lower global temperatures in a similar way to a volcanic eruption.

Other ideas include deliberately modifying clouds to make them more reflective or sending giant mirrors into space.

The proposals may sound futuristic, but the notion of engineering the climate in order to limit sunlight has been debated by scientists and politicians for more than 50 years.

However, these debates have always proved controversial, meaning – apart from studies based on computer simulations – little field research into solar geoengineering has been carried out. (See: How does this compare to past solar geoengineering efforts in the UK and globally?)

Aria’s new research programme aims to invest £57m in 21 solar geoengineering research projects globally.

This – along with a separate £10m scheme from the UK Research and Innovation body – means the UK is now one of the world’s biggest funders of solar geoengineering research.

Announcing the details of the scheme, Aria said its motivation for launching the research programme was “the possibility of encountering damaging climate tipping points”.

Out of the £57m, around £24.5m ($33m) will be spent on “controlled, small-scale outdoor experiments”, according to Aria.

These include attempts to thicken Arctic sea ice, brighten clouds above Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and to float weather balloons containing natural minerals high in the stratosphere, which will be retrieved after “hours or weeks”.

All outdoor experiments will be “scrutinised” by an oversight committee chaired by Prof Piers Forster, a leading climate scientist who is the founding director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures at the University of Leeds.

In a note released alongside news of the research funding, the oversight committee said it does “not exist to legitimise this programme”, adding:

“We advise Aria on the risks and benefits of supporting proposed creator projects and how best to work with and across creator teams to support learning and to help ensure that findings are contextualised and communicated appropriately alongside [climate] mitigation and adaptation options.”

Aria is a “high-risk, high-reward” government research agency that was formally established through an act of parliament in 2023.

It was originally conceptualised by Dominic Cummings, a controversial former adviser of then prime minister Boris Johnson.

According to Nature, Aria was modelled on the “famed US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, which helped to pioneer some of the world’s most consequential technologies, including the internet and personal computers”.

In its recent coverage, the Daily Telegraph described Aria as a “secretive government unit”.

Aria itself has said that it aims to be fully transparent about its solar geoengineering programme, which was its motivation for publicly announcing its spending on the 21 projects involved.

How does this compare to past solar geoengineering efforts in the UK and globally?

As mentioned above, the idea of solar geoengineering has been debated for more than 50 years. However, its controversial nature has meant that, until now, very few field experiments have been carried out.

In 2010, there was an attempt to carry out field research in the UK by the Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering (SPICE) project, which was headed by Dr Matthew Watson at the University of Bristol and involved scientists from the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh.

The project aimed to “investigate the effectiveness” of solar geoengineering, in part by releasing the equivalent of a bathtub of water high into the atmosphere above Norfolk.

However, it was met with fierce opposition by some campaign groups. In 2012, the team ended the project, citing issues with intellectual property and discomfort with the current lack of regulation and governance of solar geoengineering research.

(Watson is one of the recipients of Aria’s new research programme. His team has been awarded £4.3m ($5.7m) to build specialised drones to study emissions from regularly erupting volcanoes in Guatemala, Montserrat and Chile.)

Outside of the UK, another high-profile solar geoengineering experiment headed by researchers at Harvard University, called the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (Scopex), was also forced to disband following public disapproval.

In the private sector, a US start-up called Make Sunsets has begun releasing high-altitude balloons containing sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere, in an attempt to geoengineer the planet. It funds its activities by selling “cooling credits”.

The company has been banned in Mexico, where it previously launched balloons, and is currently being investigated by the US Environmental Protection Agency.

According to the online publication SRM360, funding for solar geoengineering has increased from $34.9m in 2010-14 to $112.1m in 2020-24. The vast majority of funding is concentrated in global-north countries and about half of all funding comes from philanthropic sources.

This week, scientists and policymakers are meeting in Cape Town, South Africa for the largest summit to date on the scientific, social and political implications of solar geoengineering.

Countries have agreed to a de facto moratorium on large-scale solar geoengineering under the Convention on Biological Diversity, a UN treaty that aims to protect biodiversity. (However, it is not legally binding.)

Why do some scientists say solar geoengineering research is needed?

Scientists agree that cutting global greenhouse emissions as soon as possible is key to tackling climate change.

But global emissions are still rising – and the prospect of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the ambition of the landmark Paris Agreement, without first “overshooting” the target is fast vanishing.

This has led some scientists to call for more research into solar geoengineering ideas, including through small-scale experiments and trials.

Research based on computer modelling indicates that artificially cooling the planet by releasing reflective aerosols into the stratosphere using specialised planes could be effective at offsetting a range of climate impacts, such as more intense heatwaves and flooding, melting sea ice and higher tropical storm risk.

(One solar geoengineering scientist has estimated that halving global warming with reflective aerosols would involve a specialised fleet of about 100 planes releasing 1m tonnes of sulfuric acid each year by 2070.)

However, this type of solar geoengineering would not address rising CO2 levels, which are causing oceans to become more acidic and crops to become less nutritious, among other issues.

Some scientists have raised concerns that, if aerosols were used to address global warming, the world could be left at risk of a “termination shock”. That is, if aerosols were released and then suddenly stopped – as a result of political disagreement or a terrorist attack, for example – global temperatures could rapidly rebound.

This sharp temperature change could be “catastrophic” for wildlife, modelling studies have suggested. However, other research argues that the likelihood of a termination shock has been “overplayed” and that measures could be put in place to ensure that the risk is minimised.

There is also a risk that deploying aerosols from just one spot on Earth could cause uneven impacts for people. One research paper based on modelling found that releasing aerosols in just the northern hemisphere could lead to a decrease in rainfall – and, therefore, an enhanced drought risk – in India and the African Sahel.

Ultimately, advocates of solar geoengineering research tend to argue that the only way to understand more about the efficacy and risks of the technology is to study it further, whereas opponents say more research could be a “slippery slope” towards deployment.

Why are there social and ethical concerns around solar geoengineering?

As well as scientific uncertainties, experts have long warned that solar geoengineering poses large social, ethical and governance challenges.

Some scientists and campaigners are fundamentally opposed to the idea of manipulating the climate further in order to try to repair some of the damage caused by fossil-fuel emissions.

Writing in the Guardian, climate scientists Prof Raymond Pierrehumbert and Dr Michael Mann described Aria’s research programme as “like using aspirin for cancer”.

Indigenous groups have strongly opposed the idea of solar geoengineering and its research, often arguing it goes against their beliefs about living in harmony with nature.

Some scientists and campaign groups also believe that solar geoengineering could be viewed by politicians and the public as a quick “technofix” to climate change. If more research and development is channelled into these techniques, they argue, people may start to backpedal on their promises to cut their emissions.

This is often referred to as the “moral hazard” dilemma.

But other researchers have urged caution on this idea. One reason for this is that social experiments conducted with members of the public have found little evidence of the moral hazard problem existing in practice.

Advocates of solar geoengineering research say it should be viewed as a “supplement” to climate mitigation efforts rather than a “substitute” or “quick fix”.

However, many experts and commentators have pointed out that the technology presents a very large global governance challenge.

A fair and just deployment of solar geoengineering would require agreement between countries, experts have reasoned. At present, it is difficult to picture a global forum that could garner such collaboration, they say.

Prof Alan Robock, a professor in the department of environmental sciences at Rutgers University, summarised this issue neatly in a conversation with Carbon Brief in 2018, when he said:

“You’re asking if the world can come together and agree on geoengineering without agreeing on mitigation. I think the answer is for us to agree on mitigation. Paris is the first step, the pledges made there aren’t enough but have got to increase.”

Another concern is the “free-driver problem”, an idea that refers to the potential for a single country, group or even individual to unilaterally deploy solar geoengineering, even if it might cause negative impacts for others. This concern arises from the fact that solar geoengineering would be relatively cheap to carry out.

It has been argued that the free-driver problem poses a larger concern than ever in today’s increasingly polarised world, where lone politicians and billionaires hold large amounts of power.

These serious social and governance issues prompt some experts to say solar geoengineering should not be researched at all, but others to say it should be researched to try to address concerns.

Out of Aria’s £57m for solar geoengineering research, around £2.8m ($3.7m) is earmarked for governance and ethics projects.

In its latest assessment for how the world can address climate change, the world’s authority on climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), notes that there is “high agreement” among research papers that solar geoengineering “cannot be the main policy response to climate change and is, at best, a supplement to achieving sustained net-zero”.

The assessment also notes that solar geoengineering “may introduce novel risks for international collaboration and peace”.