Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump

Simon Evans

01.30.26Simon Evans

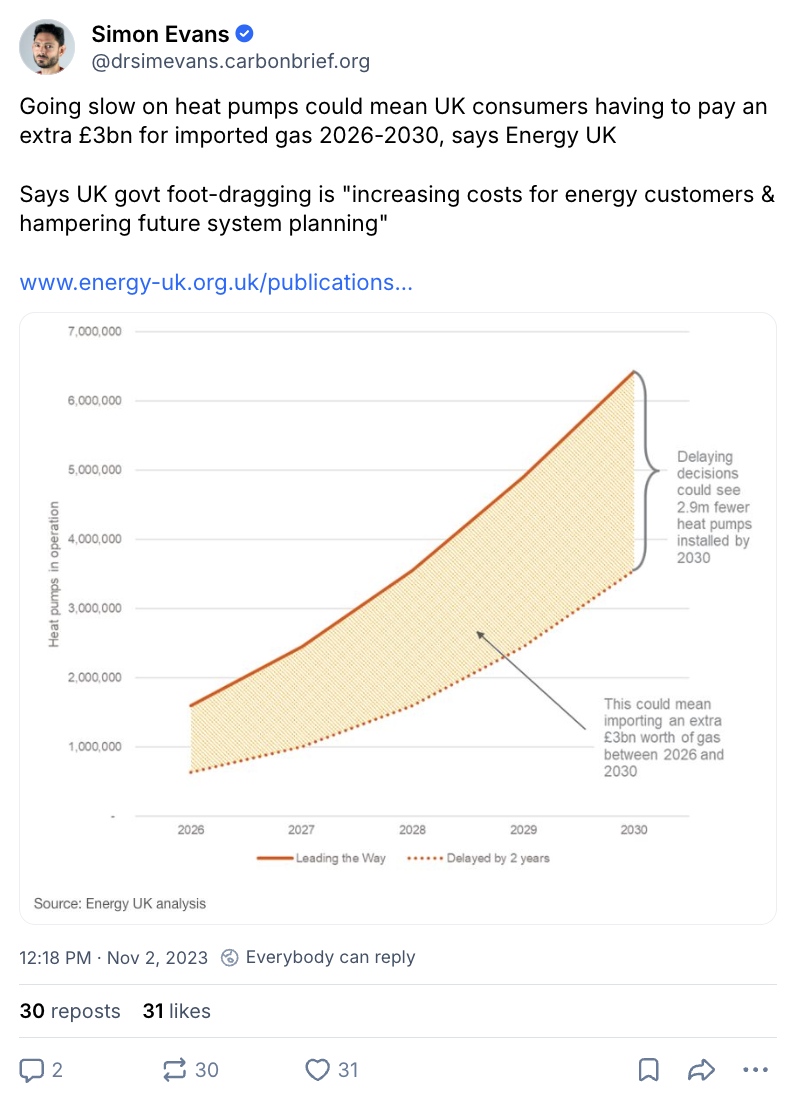

30.01.2026 | 2:55pmElectric heat pumps are set to play a key role in the UK’s climate strategy, as well as cutting the nation’s reliance on imported fossil fuels.

Heat pumps took centre-stage in the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan”, which said that they could also help cut household energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” a year.

Similarly, innovation agency Nesta estimates that typical households could cut their annual energy bills nearly £300 a year, by switching from a gas boiler to a heat pump.

Yet there has been widespread media coverage in the Times, Sunday Times, Daily Express, Daily Telegraph and elsewhere of a report claiming that heat pumps are “more expensive” to run.

The report is from the Green Britain Foundation set up by Dale Vince, owner of energy firm Ecotricity, who campaigns against heat pumps and invests in “green gas” as an alternative.

One expert tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”, while another says that it “combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture”.

This factcheck explains how heat pumps can cut bills, what the latest data shows about potential savings and how this information was left out of the report from Vince’s foundation.

How heat pumps can cut bills

Heat pumps use electricity to move heat – most commonly from outside air – to the inside of a building, in a process that is similar to the way that a fridge keeps its contents cold.

This means that they are highly efficient, adding three or four units of heat to the house for each unit of electricity used. In contrast, a gas boiler will always supply less than one unit of heat from each unit of gas that it burns, because some of the energy is lost during combustion.

This means that heat pumps can keep buildings warm while using three, four or even five times less energy than a gas boiler. This cuts fossil-fuel imports, reducing demand for gas by at least two-fifths, even in the unlikely scenario that all of the electricity they need is gas-fired.

Since UK electricity supplies are now the cleanest they have ever been, heat pumps also cut the carbon emissions associated with staying warm by around 85%, relative to a gas boiler.

Heat pumps are, therefore, the “central” technology for cutting carbon emissions from buildings.

While heat pumps cost more to install than gas boilers, the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan” says that they can help cut energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” per year.

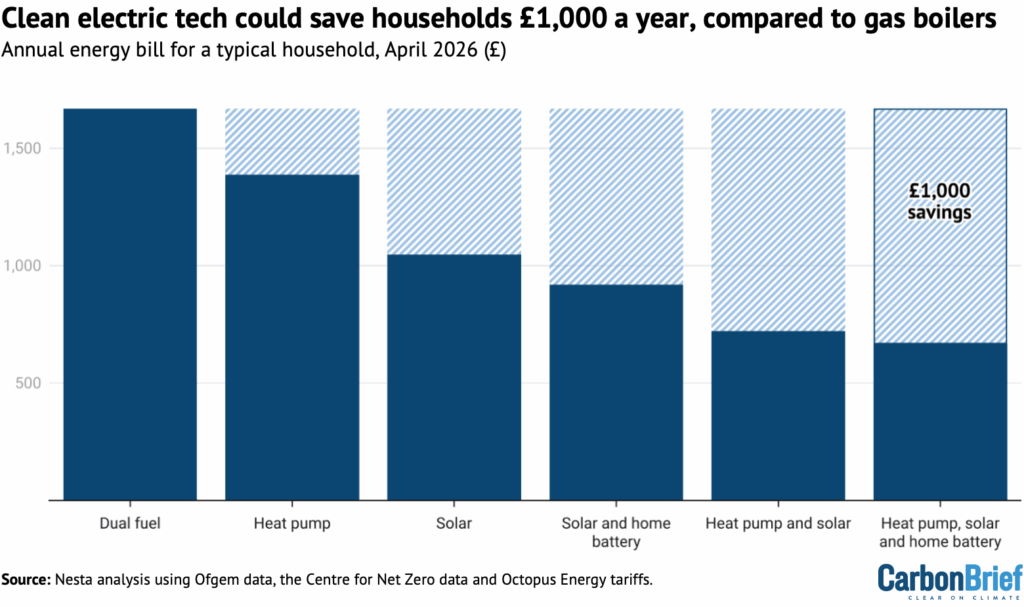

Similarly, Nesta published analysis showing that a typical home could cut its annual energy bill by £280, if it replaces a gas boiler with a heat pump, as shown in the figure below.

Nesta and the government plan say that significantly larger savings are possible if heat pumps are combined with other clean-energy technologies, such as solar and batteries.

Both the government and Nesta’s estimates of bill savings from switching to a heat pump rely on relatively conservative assumptions.

Specifically, the government assumes that a heat pump will deliver 2.8 units of heat for each unit of electricity, on average. This is known as the “seasonal coefficient of performance” (SCoP).

This figure is taken from the government-backed “electrification of heat” trial, which ran during 2020-2022 and showed that heat pumps are suitable for all building types in the UK.

(The Green Britain Foundation report and Vince’s quotes in related coverage repeat a number of heat pump myths, such as the idea that they do not perform well in older properties and require high levels of insulation.)

Nesta assumes a slightly higher SCoP of 3.0, says Madeleine Gabriel, the organisation’s director of sustainable future. (See below for more on what the latest data says about SCoP in recent installations.)

Both the government and Nesta assume that a home with a heat pump would disconnect from the gas grid, meaning that it would no longer need to pay the daily “standing charge” for gas. This currently amounts to a saving of around £130 per year.

Finally, they both consider the impact of a home with a heat pump using a “smart tariff”, where the price of electricity varies according to the time of day.

Such tariffs are now widely available from a variety of energy suppliers and many have been designed specifically for homes that have a heat pump.

Such tariffs significantly reduce the average price for a unit of electricity. Government survey data suggests that around half of heat-pump owners already use such tariffs.

This is important because on the standard rates under the price cap set by energy regulator Ofgem, each unit of electricity costs more than four times as much as a unit of gas.

The ratio between electricity and gas prices is a key determinant of the size and potential for running-cost savings with a heat pump. Countries with a lower electricity-to-gas price ratio consistently see much higher rates of heat-pump adoption.

(Decisions taken by the UK government in its 2025 budget mean that the electricity-to-gas ratio will fall from April, but current forecasts suggest it will remain above four-to-one.)

In contrast, Vince’s report assumes that gas boilers are 90% efficient, whereas data from real homes suggests 85% is more typical. It also assumes that homes with heat pumps remain on the gas grid, paying the standing charge, as well as using only a standard electricity tariff.

Prof Jan Rosenow, energy programme leader at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report uses “worst-case assumptions”. He says:

“This report cherry-picks assumptions to reach a predetermined conclusion. Most notably, it assumes a gas boiler efficiency of 90%, which is significantly higher than real-world performance…Taken together, the analysis combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture.”

Similarly, Gabriel tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”. She explains:

“Dale Vince has drawn some very strong conclusions about heat pumps from quite flimsy data. Like Dale, we’d also like to see electricity prices come down relative to gas, but we estimate that, from April, even a moderately efficient heat pump on a standard tariff will be cheaper to run than a gas boiler. Paired with a time-of-use tariff, a heat pump could save £280 versus a boiler and adding solar panels and a battery could triple those savings.”

What the latest data shows about bill savings

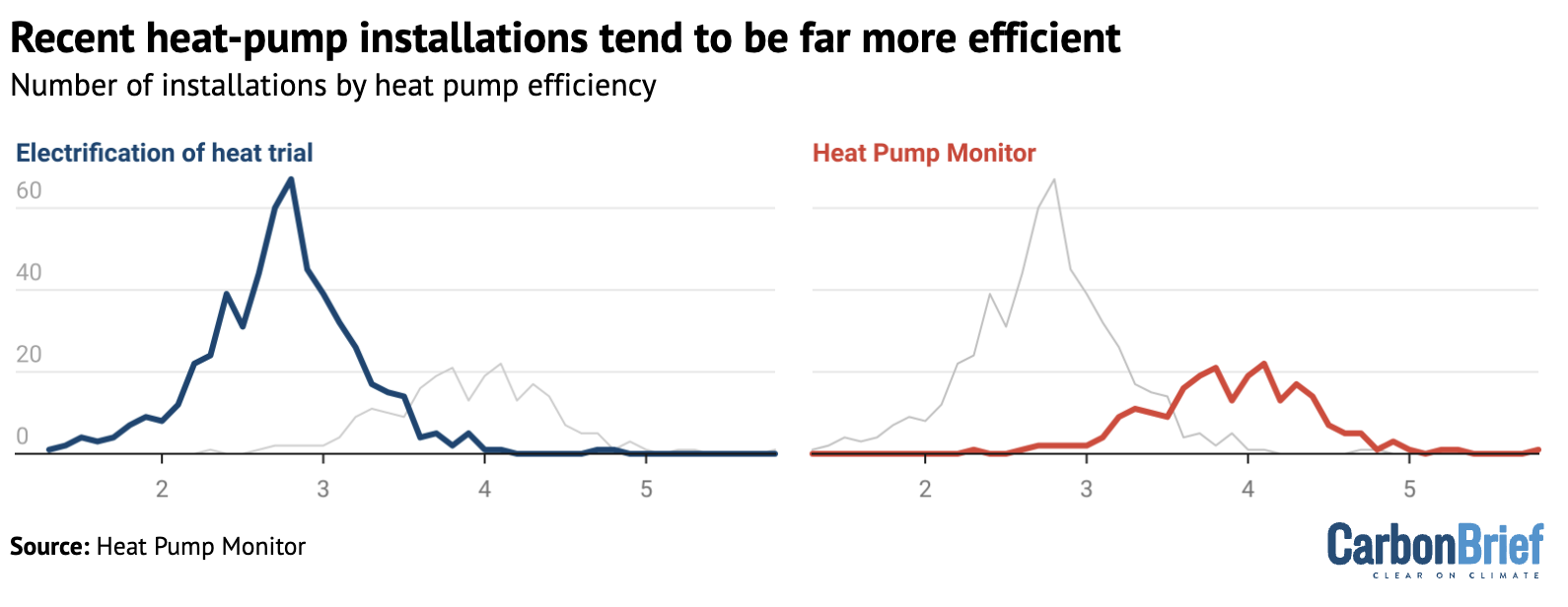

The efficiency of heat-pump installations is another key factor in the potential bill savings they can deliver and, here, both the government and Vince’s report take a conservative approach.

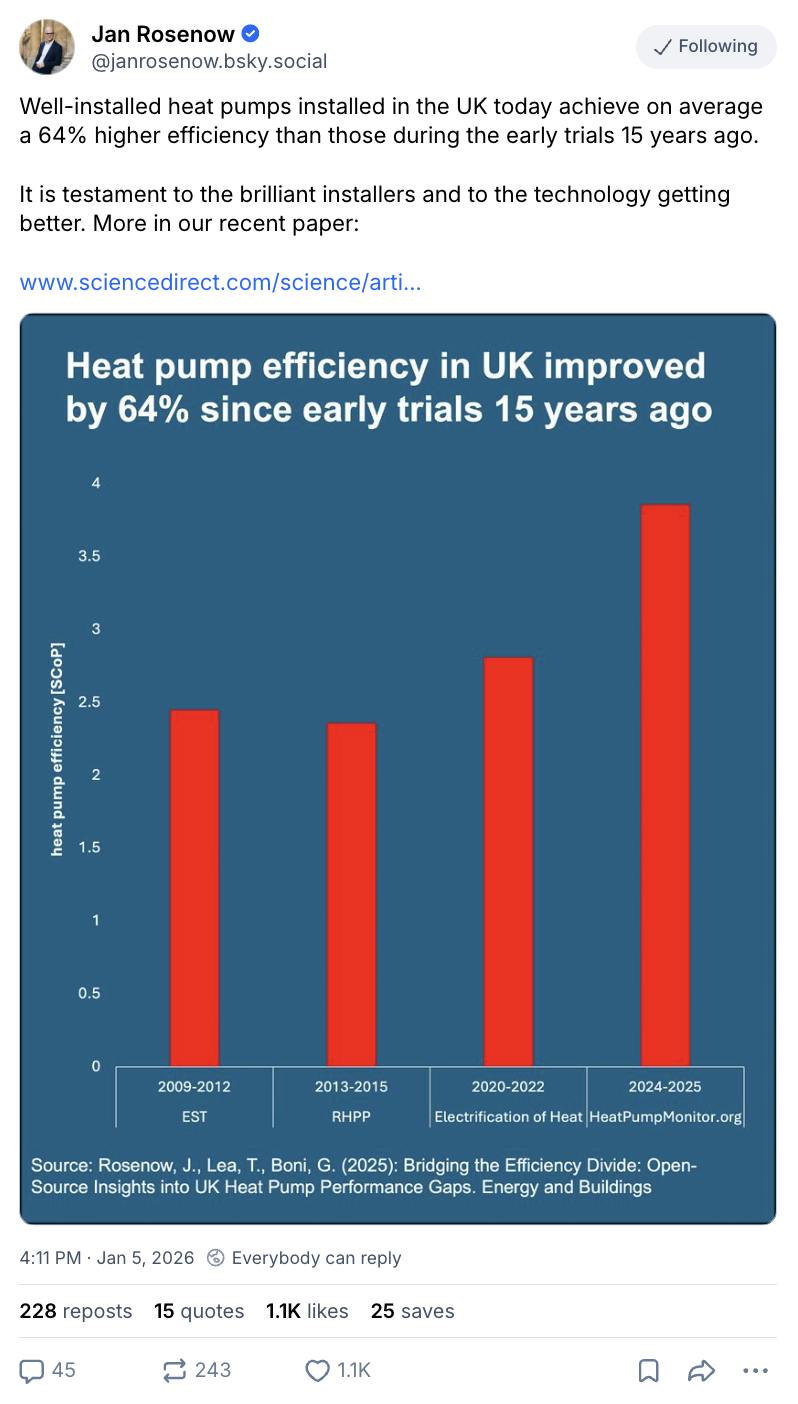

They rely on the “electrification of heat” trial data to use an efficiency (SCoP) of 2.8 for heat pumps. However, Rosenow says that recent evidence shows that “substantially higher efficiencies are routinely available”, as shown in the figure below.

Detailed, real-time data on hundreds of heat pump systems around the UK is available via the website Heat Pump Monitor, where the average efficiency – a SCoP of 3.9 – is much higher.

Homes with such efficient heat-pump installations would see even larger bill savings than suggested by the government and Nesta estimates.

Academic research suggests that there are simple and easy-to-implement reasons why these systems achieve much higher efficiency levels than in the electrification of heat trial.

Specifically, it shows that many of the systems in the trial have poor software settings, which means they do not operate as efficiently as their heat pump hardware is capable of doing.

The research suggests that heat pump installations in the UK have been getting more and more efficient over time, as engineers become increasingly familiar with the technology.

It indicates that recently installed heat pumps are 64% more efficient than those in early trials.

Notably, the Green Britain Foundation report only refers to the trial data from the electrification of heat study carried out in 2020-22 and the even earlier “renewable heat premium package” (RHPP). This makes a huge difference to the estimated running costs of a heat pump.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that a typical household could cut its annual energy bills by nearly £200 with a heat pump – even on a standard electricity tariff – if the system has a SCoP of 3.9.

The savings would be even larger on a smart heat-pump tariff.

In contrast, based on the oldest efficiency figures mentioned in the Green Britain Foundation report, a heat pump could increase annual household bills by as much as £200 on a standard tariff.

To support its conclusions, the report also includes the results of a survey of 1,001 heat pump owners, which, among other things, is at odds with government survey data. The report says “66% of respondents report that their homes are more expensive to heat than the previous system”.

There are several reasons to treat these findings with caution. The survey was carried out in July 2025 and some 45% of the heat pumps involved were installed between 2021-23.

This is a period during which energy prices surged as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting global energy crisis. Energy bills remain elevated as a result of high gas prices.

The wording of the survey question asks if homes are “more or less expensive to heat than with your previous system” – but makes no mention of these price rises.

The question does not ask homeowners if their bills are higher today, with a heat pump, than they would have been with the household’s previous heating system.

If respondents interpreted the question as asking whether their bills have gone up or down since their heat pump was installed, then their answers will be confounded by the rise in prices overall.

There are a number of other seemingly contradictory aspects of the survey that raise questions about its findings and the strong conclusions in the media coverage of the report.

For example, while only 15% of respondents say it is cheaper to heat their home with a heat pump, 49% say that one of the top three advantages of the system is saving money on energy bills.

In addition, 57% of respondents say they still have a boiler, even though 67% say they received government subsidies for their heat-pump installation. It is a requirement of the government’s boiler upgrade scheme (BUS) grants that homeowners completely remove their boiler.

The government’s own survey of BUS recipients finds that only 13% of respondents say their bills have gone up, whereas 37% say their bills have gone down, another 13% say they have stayed the same and 8% thought that it was too early to say.