Roz Pidcock

02.04.2014 | 1:00pmFrom posing a threat to natural ecosystems to damaging business, property and livelihoods, a report out this week from the UN’s official climate body reviews the wide-ranging damages extreme flooding can cause.

With the UK currently dealing with the impact of widespread flooding, we look at what the report has to say about how serious a risk it could be in the future as the climate changes further.

Getting wetter

Last September, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a bumper assessment of how and why the climate is changing, including projections for how everything from rainfall to arctic sea ice is likely to change in the coming decades.

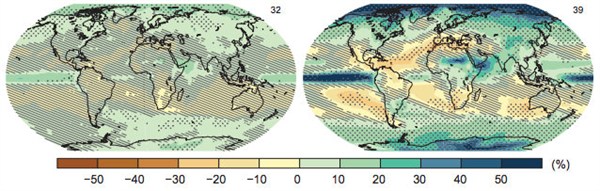

Scientists expect a warming world to lead to more extreme rainfall. The image below shows the UK receiving about 10 per cent more rainfall on average per year by 2100 (right) compared to 1986-2005 (left).

The UK is set to see about a 10 per cent rise in annual average rainfall by 2100 (right) compared to the period 1985-2005 (left). Source: IPCC 5th Assessment Report Sumary for Policymakers (p20).

It’s not just the total amount of rainfall that scientists expect to increase. The IPCC report also predicts Europe and the UK is “very likely” to see more heavy rainfall events by the end of the century. A lot of rain falling in a short space of time raises flood risk, and there’s already evidence heavy rainfall events are getting more frequent in the UK due to climate change, as a report released last week from the Met Office explains.

Heavier rainfall plus sea level rise – which make storm surges bigger and more likely to breach coastal defences – has scientists warning of a greater flood risk in the UK as the climate warms. As professor Richard Allan from Reading University told us recently:

“[W]henever we have heavy (and prolonged) rainfall events in the future, we can expect them to be more intense – along with the risk of flooding.”

Rising sea level due to climate change makes storm surges bigger and more likely to breach coastal defences.

A new report

The IPCC has just released the second part of its comprehensive overview of climate change science. It looks at the impacts of climate change across the globe, from farming to flooding.

With floods and climate change back on the news agenda, we’ve reviewed what the report has to say about future flooding and its impacts.

How much flooding will the UK get?

Floods are the most frequently-occurring type of natural disaster, the report says. And as flood risk in the UK rises, so does the risk to society.

According to one study the new report cites, warming of 3.5 to 4.8 degrees Celsius by the 2080s – which is what the IPCC expects if emissions stay high – would expose an additional 250,000 to 400,000 people in Europe to river flooding, and potentially up to 5.5 million per year to coastal flooding. The UK is likely to be one of the worst affected locations, the report suggests.

How much will it cost?

Research cited in the new IPCC report suggests flooding costs are likely to escalate with the rising risk of flooding. The report says:

“Climate change could increase the annual cost of flooding in the UK almost 15-fold by the 2080s under high emission scenarios.”

This increase is primarily due to population growth and changes in the value of buildings and infrastructure – but climate change is also partly responsible, the report points out. The UK government’s Foresight Programme, which the IPCC report also cites, estimated global warming of three to four degrees above pre-industrial levels could increase flood damage costs from 0.1 to 0.4 per cent of GDP.

Another study projects the average amount insurers pay out annually for flood damage in the UK to go up eight per cent for two degrees warming and 14 per cent for four degrees, which the IPCC thinks looks likely by around 2060 and the end of the century, respectively, if emissions stay high.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers estimates the price tag of the current flooding, in terms of lost income, repairing damage and extensive clean-up efforts, is already in the region of £600 million – and expected to rise as the bad weather continues into late February. PWC said:

“Our expectations are that the insurance industry will have up to £500m of costs from the January and December weather and the economic damage will be £630m.”

Richard Holt of Capital Economics told the Independent the area at risk represented around 13 per cent of the UK’s gross domestic product, and the loss of output in those areas would reduce GDP by over 1 per cent within a month, totalling £13.8bn. This is economists’ best estimate, but experts warn it’s hard to know the full extent while a lot of the country still remains flooded.

Economist Richard Holt of Capital Economics talking to CNBC about the economic costs of the recent sever floods in the UK. Source: CNBC

Overflowing sewers

The new IPCC report identifies climate change as a key factor affecting Britain’s present and future sewer systems. A recent study cited in the report looked at cities across Europe, the US, Canada, Asia and Australia, and estimates a typical increase in rainfall intensity of 10 to 60 per cent has in some cases increase in the frequency of sewer flooding by up to 400 per cent.

Another study estimates the volume of sewage released to the environment by flooding-induced sewage overflow spills looks set to increase by 40 per cent by 2080.

In this most recent case of flooding, urban drains have been struggling to cope with the volume of water flowing into them.

Transport disruption

The new report notes persistent, heavy rainfall and flooding can disrupt important transport links, something we’re seeing a lot of in the UK at the moment.

Submerged tracks after weeks of heavy rain are disruption to rail travel.

As well as the obvious direct impacts of flooding on rail networks, the report explains how possible knock-on effects are more difficult to assess, and often overlooked. The report says:

“Studies have often examined the direct impacts of flooding on transport infrastructure, but the indirect costs of delays, detours, and trip cancellation may also be substantial.”

And while it’s the trains that seem to be most affected in the UK at the moment, should future flooding affect the capital city the tube network could face major disruption too. The report notes:

“Many cities â?¦ depend on underground electric rail systems which require protection from the considerable risk from flooding – such as New York and London. Adapting all these systems to the impacts of climate change (including hot days, storms and sea-level rise) poses many challenges).”

Building on floodplains

While scientists are confident heavier rainfall runs a greater risk of flooding, the new IPCC report highlights how the choices we make about land use can increase the flood risk too. Building on floodplains is a big problem, for example. It notes:

“Globally, the frequency of river flood events has been increasing, as well as economic losses, due to the expansion of population and property in flood plains.”

The government’s climate change advisor, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), found in 2012 that England’s floodplains have seen more property development than other areas over the past 10 years – and one in five of those properties is at risk of flooding. Between 2001 and 2011, 200,000 homes were built in floodplains – and since the government came in, changes to planning regulations have made building in vulnerable areas easier.

Building on floodplains increases flood risk, the Committee on Climate Change warns.

Why build on floodplains? Opportunities for development are just too tempting a prospect for local governments, the IPCC report suggests:

“In most nations, urban governments find it difficult to prevent new developments on sites at risk of flooding, especially in locations attractive for housing or commerce, even when there are laws and regulations in place to prevent this â?¦ There can also be vested interests and trade-offs where near-term development conflicts with longer-term adaptation and resilience goals”

Low natural drainage

Many people have raised the question in light of the recent flooding that paving over soil could be exacerbating the problem, because rainwater is falling on concrete rather than being soaked up by the ground.

The CCC recently told the BBC building practices such as paving over gardens, loss of urban green space and building on the floodplain mean the UK is increasingly vulnerable to floods.

Paving over gardens reduces the ground’s ability to drain rainwater naturally, increasing flood risk.

Preserving or developing natural drainage – which involves taking advantage of trees, plants and soil to manage where water flows and gets absorbed – can help prevent floods. The IPCC report highlights why soil is so important for keeping flood waters at bay, especially in urban areas. It says:

“Maintaining soil water retention capacity â?¦ contributes to reduce risks of flooding as soil organic matter absorbs up to twenty times its weight in water”

What needs to happen now?

Adaptation measures to build resilience to extreme rainfall and flooding can make a difference, the IPCC report notes – by bolstering coastal defences, for example. But there’s a limit to how far adaptation can go. It says:

“[W]hile adapting buildings in coastal communities and upgrading coastal defences can significantly reduce adverse impacts of sea level rise and storm surges, they cannot eliminate these risks, especially as sea levels will continue to rise over time. Managed retreat is likely to become a necessary response.”

Clearly, emissions need to come down to limit the extent of future risk. In the meantime, it’s important to ensure useful insurance schemes exist to cover those at risk. Swenja Surminski, a senior research fellow at the LSE’s Grantham Research Institute and its Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, previously told Carbon Brief:

“[Insurance should] trigger behaviour change, especially in the government. It should lead to fewer houses being built on the floodplain, not business as usual, for example.”

We’ve written more about criticisms of the government’s flood protection insurance scheme here.

Informed policy decisions to keep risks at an acceptable level should mean taking heed of the scientific evidence current and future risks – and the new report lays them out fairly clearly. Current events demonstrate the risks of not being prepared for these events when they strike.

Note: This article was originally posted in February 2014. It has since been updated.