Mat Hope

23.09.2014 | 12:01amTV audiences around the world aren’t hearing much about climate science.

That’s the main conclusion of a new study looking at how TV news covered the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) three big reports earlier this year.

While the IPCC reports made a small splash in the print media, the same wasn’t true of television news. The main news bulletins in some countries barely covered the reports. And when they did, they used an old-fashioned “doom” narrative to explain them, research by Oxford University’s Reuters Institute finds.

That’s concerning, because many people still get their news from the TV, and place particular trust in TV news to deliver a balanced account of climate science.

Here’s which channels covered the reports, how, and why it matters.

Country divergence

The IPCC’s first report on the sciencific foundations of climate change was launched in October 2013. A second report on the impacts of climate change was released the final day of March 2014, with a third report looking at policies to cut emissions following a couple of weeks later.

The Reuters Institute looked at how a selection of news bulletins in the UK, China, India, Brazil, Australia and Germany covered all three reports on their launch day, and the day before.

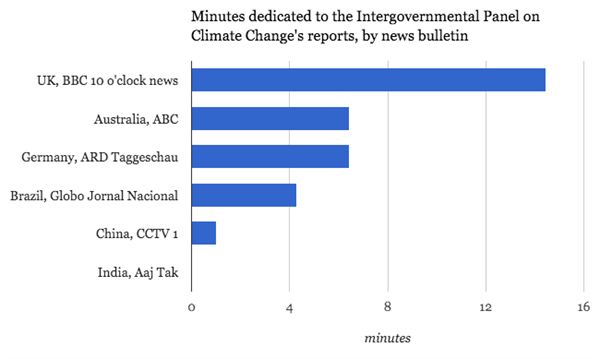

13 out of the 36 key news bulletins the Reuters Institute studied covered the IPCC reports. That adds-up to about 34 minutes of airtime. This chart shows how many minutes each of the bulletins gave to the reports:

The UK’s BBC was way out ahead, giving almost 15 minutes in total for all three reports, across four segments. Germany and Australia’s bulletins were next, dedicating a total of almost seven minutes to the reports.

It was a different story in the three less-developed countries included in the study. Brazil’s bulletin covered the first two reports in a total of four and half minutes. China’s main TV channel dedicated just 40 seconds to the first report. The Indian channel included in the study didn’t cover any of the reports at all.

That’s likely to be because it was election season in India, the study says. The country held general elections between April and May 2014, so the second and third reports in particular got lost in campaigning noise.

In China, the main news network chose to barely cover the IPCC’s landmark reports because it didn’t think there was anything “new” in them, the study says:

“The Chinese government has long recognized the existence of climate change and made efforts to face the challenges. The repetition of the same viewpoint is not attractive either to the media or its audiences”.

This contrasts with the amount of attention China’s media gives the UN’s climate meetings.

The international negotiations are given a lot more TV time, the study says, because “the Chinese government encourages journalists to attend these meetings to be able to be put over its point of view domestically and internationally, particularly as in recent UN meetings they feel their position has been distorted by the Western media”.

Disaster framing

So what filled those 34 minutes of airtime? Mainly doom-and-gloom stories, the study says.

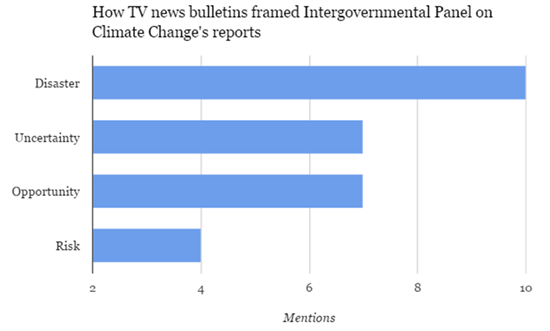

This chart shows how often the IPCC reports were linked to the themes of disaster, uncertainty, managing risk, and opportunities:

As you can see, the news bulletins most often framed their segments on the IPCC reports in terms of the potential disasters associated with climate change.

This is not unusual, the study suggests. Journalists can construct a strong narrative around a looming disaster, providing an easily communicated tale: if people carry on emitting greenhouse gases, bad things will happen.

In contrast, uncertainty and risk are much more complicated concepts, and TV news producers simply don’t have the time to explain them.

The study questions the effectiveness of using doom and gloom to engage the public about climate change, however. Emphasising more hopeful messages, such as the economic opportunities of decarbonisation, may be more effective, it says.

Scientific presence

While the way in which TV news covered the IPCC reports wasn’t unusual, the news programmes’ choice of interviewees was. The vast majority of interviews were with scientists that had worked on the IPCC reports, the study found.

Of the 35 segments that contained interviews, 19 were with IPCC authors. That means climate scientists directly involved with the IPCC’s process were by far and away the most represented group in the bulletins.

This again contrasts with media coverage of the UN’s international climate negotiations. In newspaper coverage of the meeting in Copenhagen in 2009, only 12 per cent of interviewees were scientists, the study says. In TV news coverage of the IPCC reports, it was 54 per cent.

So while there wasn’t much coverage of the IPCC reports in TV news bulletins overall, scientific voices dominated what little there was.

Not much news

The Reuters Institute’s research suggests TV news’ appetite for climate change stories is limited. Many are competing in a market where ratings rule, meaning more politics and celebrity stories and less science, the study notes.

It suggests that the IPCC could release a single synthesis report, rather than three, to try and generate more media coverage. But most of all, it says the IPCC needs to try and move away from stories that emphasise the negative aspects of climate change.

Offering solutions is more helpful than describing disasters, it says, which could be the key to getting climate change on TV.

Update, 23/09: The graphs were updated.