In-depth: Is the 1.5C global warming goal politically possible?

Sophie Yeo

06.15.15Sophie Yeo

15.06.2015 | 2:30pmFor the past five years, international climate change negotiations have been guided by the principle that the rise in global average temperatures should be limited to “below 2C above pre-industrial levels”.

Is this goal adequate? Probably not, according to a report conducted by the UN and launched at the climate change negotiations in Bonn.

Containing the views of 70 scientists gathered together in a process called the “structured expert dialogue”, the report warns that even current levels of global warming – around 0.85C – are already intolerable in some parts of the world. It says:

“Some experts warned that current levels of warming are already causing impacts beyond the current adaptive capacity of many people, and that there would be significant residual impacts even with 1.5C of warming (e.g. for sub-Saharan farmers), emphasising that reducing the limit to 1.5C would be nonetheless preferable.”

This report provides the evidence base for discussions at UN level over whether the world is being ambitious enough on long-term action to tackle climate change.

Climate talks in Bonn

While the message of the report is clear, it does not close the current chasm between climate science and policy.

At UN climate negotiations in Bonn last week, the report and its findings were subject to intense scrutiny and discussion by diplomats from around the world.

It is these policymakers – not the scientists – who get the final say on whether the findings become the new basis for future political decisions, embedded in a new international climate deal set to be signed at the end of this year in Paris.

The views of diplomats around the world differ widely on how the findings of the report should be incorporated.

At the most hopeful end of the scale, countries want to include an official decision that “there is a need to strengthen the global goal on the basis of limiting warming to below 1.5C above pre-industrial levels”.

A minority would rather ignore the report – the product of two years’ work – altogether.

In any case, two weeks of discussions ended in an outcome that most had hoped to avoid: just two short sentences acknowledging that a report had been written, and that countries would continue to discuss it when they meet again in Paris.

History

The 2C temperature goal was the product of the UN’s 2010 climate conference in Cancun, Mexico.

It is often painted as a scientific threshold, but the decision was, ultimately, a political one. For some of the most vulnerable nations, it was a compromise. Scientists say that a 2C world will severely impact agriculture, sea levels, coral reefs and Arctic ice, with the world’s poorest people hit first and hardest.

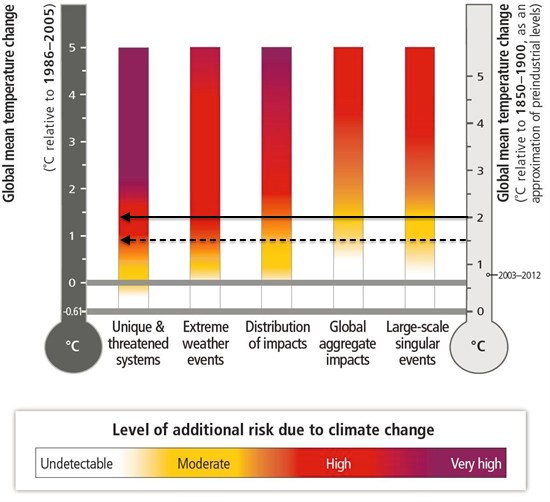

Source: IPCC WG-II, Summary for Policymakers, p. 39. Dotted and solid lines by Carbon Brief, to show impacts at 1.5 and 2C.

To ease the political deadlock, countries agreed on a process to assess the adequacy of the 2C goal, and, in particular, whether a 1.5C target might be preferable in light of the science.

The 34.5 hours of consultations that took place between 70 scientific experts culminated in the report discussed by policymakers in Bonn.

While it did not make any official recommendations, it was clear that keeping temperatures below 1.5C would avoid some of the more severe impacts of climate change that would set in at around 2C.

Written by the co-facilitators of the two-year dialogue, Andreas Fischlin and Zou Ji, the report states that the differences between 1.5 and 2C were likely to be “meaningful”, increasing the chance of extreme events and passing irreversible tipping points in the climate system.

And it points out that technology required for limiting temperatures below 1.5C are no different from those required for 2C – although they would need to be deployed faster, meaning that the costs would be higher.

Costs are not the only potential drawback. It also adds that a 1.5C target would mean relying on negative emissions technologies, which can absorb carbon dioxide out of the air.

One means to do this is planting large areas of trees, burning them as biomass and permanently storing underground the resulting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Finding enough land for this could prove challenging, particularly if it comes into competition with food production.

In addition, the report points out that the science on the impacts of climate change at 1.5C is less robust than the science of 2C. “Consequently, assessing the differences between the future impacts of climate risks for 1.5C and 2C of warming remains challenging,” it says.

Nonetheless, the overriding message is clear: the world at 1.5C warmer will be significantly safer than it would be at 2C.

Guardrails versus defence lines

The report recommends some adjustments to the 2C goal.

But the adjustments it suggests are to the language used to describe the goal, rather than to lower the target to 1.5C.

Instead of using the metaphor of a “guardrail” to describe the 2C, countries should instead see it as a “defence line”, the report says. Keeping with the military imagery, Andreas Fischlin, co-facilitator of the scientific review of the goal, describes it to Carbon Brief as follows:

“2C is the really very last retreat that we defend at all costs, and the goal is actually to keep global warming as low as possible. That is somehow a new idea.”

The difference is subtle. Rather than an official recommendation to strengthen the target, it simply asks countries to recognise that a 2C target cannot scientifically be considered safe as far as climate impacts are concerned – to acknowledge the facts, while not necessarily asking people to act on them.

A negotiator from Switzerland told Carbon Brief that his delegation supported officially incorporating this idea in the Paris deal. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s to really bring the science into the process and reflect that we did that in a decision.”

For some diplomats involved in the process, simply recognising that the current goal is too weak will do little to calm their nerves about the future of their countries in the face of increasingly severe climate impacts. They want to see concrete policies pinned down within the UN process.

Rueanna Haynes, a negotiator from Trinidad and Tobago representing the small island states (a negotiating bloc known as AOSIS), tells Carbon Brief:

“We were very much in favour of a substantive outcome in line with what we see was the underlying message coming from the structured expert dialogue, which was that a 2C goal is inadequate and needs to be strengthened.”

Lively debate

The UN’s report is not the first time this issue has garnered attention. Researchers are beginning to come forward to fill the knowledge gap that exists between 1.5 and 2C, demonstrating varying levels of optimism and cynicism.

A study published last month in Nature Climate Change modelled possible paths to a 1.5C limit. It concluded that it was still possible, but only just – and that all scenarios involved “overshooting” the emissions reductions target initially, before returning to it by 2100 through the use of negative emissions technologies.

A recent paper by Petra Tschakert, a coordinating lead author of the latest IPCC assessment report who gave evidence to the structured expert dialogue, points out the significance of the goal:

“Without a doubt, it is in the utmost interest of a large number of countries to pursue the 1.5C target, as ambitious or idealistic it may appear to date…Parties like small island states and many others whose vulnerability is extremely high and their survival at stake are the most vocal.”

Other scientists have warned that even a 2C goal is “naive”, and could harm meaningful climate action by focusing on short term fixes.

Opposition

For a number of reasons, it seems unlikely that diplomats will agree to push down the 2C target at the Paris climate conference in December. Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the UN’s body on climate change, tells Carbon Brief:

“I actually think that it’s going to be very, very difficult for countries to commit to a specific temperature today because there are many, many factors that are going to affect that. I think what is absolutely critical is to set the destination, the intent, the collective intent throughout several decades of where we want to come.”

The idea faced considerable opposition from a few powerful parties, with Saudi Arabia in the vanguard and China and India in support.

The Saudi delegation cited procedural concerns. However, few were convinced that issues such as the legal status of paper versus digital documents, to cite one example, were the real reasons their diplomats were cautious about opening the door to greater ambition on climate change.

With around 50% of its gross domestic product (GDP) coming from its oil and gas sector, the Saudis have traditionally been reluctant to agree to anything that could undermine its economy. The clampdown on emissions required by a 1.5C target would likely mean they would have to leave a lot more of their oil reserves in the ground than they would at 2C.

Saudi diplomats have previously argued that they should be given help by rich countries to diversify their economies in the context of a new global climate change agreement.

China and India are concerned that tougher climate regulations could create an extra burden for poorer nations, which want to grow their emissions as they develop.

Indian environment minister Prakash Javadekar articulated this in March when he warned: “The developed world which has occupied large carbon space today must vacate the space to accommodate developing and emerging economies.”

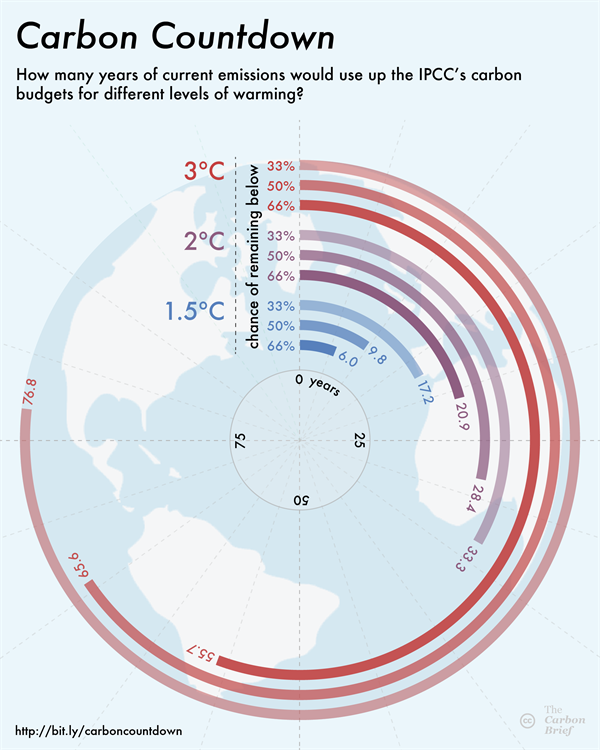

Time is tight. Statistics from last year’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicated that carbon dioxide emissions can continue on current levels for just six more years before the carbon budget associated with keeping temperatures below 1.5C is blown.

Credit: Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief

Current policies put the world on a path to exceed this by a wide margin, and there is little appetite to revise short-term ambitions.

The 40 countries which have submitted emissions reduction pledges to the UN so far have been aiming at the 2C target. These are unlikely to be revised until 2025 at the earliest (a system to “ratchet up” targets is one of the topics under discussion at the UN).

Currently, there is no framework in place to increase ambition in the period between 2015 and 2020, after the new deal is signed, but before it comes into force.

Impact

The technical difficulties and political minefields associated with introducing a new target at this late stage in the game are significant. So is there any chance that the semantic niceties of the UN’s new report will make a difference in the debate?

In the final moments in Bonn, Saudi Arabia and China sought to undermine the legitimacy of the report, removing the words “final and factual” from its official description. This suggests that a definitive statement on the inadequacy of the 2C goal was seen as a genuine threat.

Quarreling over the 2C target could even be detrimental to the UN climate talks as a whole, as it potentially distracts attention away from the need for a radical transformation, regardless of the overall goal, says the report’s co-author, Andreas Fischlin. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Those people who are particularly interested in 1.5C, they would be well advised not to push it too much in my view…because otherwise they lose it forever.

“If we stick with this question, which is considered by some as unfeasible, whatever the reason might be, then they will not agree [to a new UN deal]. Unless we have everyone on board, there will not be a signal to announce a new regime is coming.”

Nonetheless, the report puts another tool in the hands of countries, like the small island states, which would like to see greater pressure on high emitters to decarbonise their economies.

Countries have to indicate why their pledges to the UN’s climate deal are “fair and ambitious”. If diplomats formally acknowledge that even a 2C threatens lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries, that task suddenly becomes much more difficult.

Sebastien Duyck, a research at the University of Lapland who followed the talks, tells Carbon Brief:

“I think what’s useful is that this discussion about 1.5 and 2C could be used by any actors interested in questioning the level of ambition in the INDCs [intended nationally determined contributions]. I don’t think it will necessarily bring radical change in the process, but it’s a message that can be used by anyone who is really interested in having a science-based assessment of what countries are doing now.”

The “1.5C vs 2C” saga is set to be one of the many issues that continues to unfold on the stage in Paris. For some countries, they claim their economies are at stake. For others, their future.