In-depth Q&A: What is the UK’s ‘net-zero’ plan for transport?

Josh Gabbatiss

07.15.21Josh Gabbatiss

15.07.2021 | 3:24pmNet-zero domestic flights and electric lorries by 2040 are among the proposals in the UK’s long-awaited transport decarbonisation strategy.

Initially expected last year, the document is meant to flesh out government plans for achieving “net-zero” emissions across a sector that contributes more than any other to UK emissions.

The nation’s car, train, plane and ship emissions have hardly changed for three decades, despite fuel efficiency improvements and the recent rise of electric vehicles.

While the new strategy lacks new funds to address key challenges areas such as walking, cycling and public transport, it does provide more clarity on plans to entirely decarbonise the UK’s road transport within two decades.

However, experts say the government is relying too heavily on electric vehicles and avoiding difficult decisions, such as curbing flight numbers and traffic.

In this article, Carbon Brief analyses the key points from the 220-page strategy and accompanying documents, plus examines how much closer they will bring the UK to its target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

- Why does the UK need a transport decarbonisation strategy?

- How will the government encourage a switch to electric cars and vans?

- What are the new plans for trucks, buses and motorbikes?

- What does the strategy say about cutting traffic and road building?

- What are the plans to support public transport, walking and cycling?

- What are the plans for aviation and shipping?

Why does the UK need a transport decarbonisation strategy?

The transport decarbonisation plan is one of a number of government documents that are expected to pave the way for an overarching net-zero strategy ahead of the COP26 climate summit in November.

When asked about the delayed strategy in June, transport minister Rachel Maclean told MPs she had seen a final draft, but was “not satisfied” with it as it did not meet the scale of ambition required to achieve net-zero.

The plan finally emerged on 14 July. The government continued its habit of releasing a brief press release the night before, meaning none of the initial news coverage was based on an appraisal of the full report.

Ahead of #COP26, we're launching the FIRST EVER "greenprint" to end transport’s contribution to global warming by 2050 🌍✅ 1/2 pic.twitter.com/H1TWwvAdno

— Rt Hon Grant Shapps MP (@grantshapps) July 14, 2021

Transport is the UK’s largest source of emissions, responsible for 27% of greenhouse gases in 2019. Of this, 55% comes from cars and most of the remainder is from vans and lorries.

These emissions have remained roughly the same for a decade, as greater fuel efficiency has been offset by an increase in miles driven.

(While the UK’s greenhouse gas figures only include road transport, railways and domestic aviation and shipping, the government has confirmed that, starting with its sixth carbon budget, the nation’s share of international aviation and shipping emissions will be included in future climate targets.)

The government had already made some significant announcements about decarbonising transport, notably bringing forward the ban on new petrol and diesel car and van sales first to 2035 and then to 2030.

However, there have been concerns about a lack of clarity and incentives for consumers, manufacturers and transport operators on how the proposed clean transition will work.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) highlighted these ambiguities and the need for firmer policies in its recent progress report to the government.

The government said “based on the policies and ambitions laid out in this plan” the transport sector – excluding international aviation and shipping – could achieve net-zero by 2050.

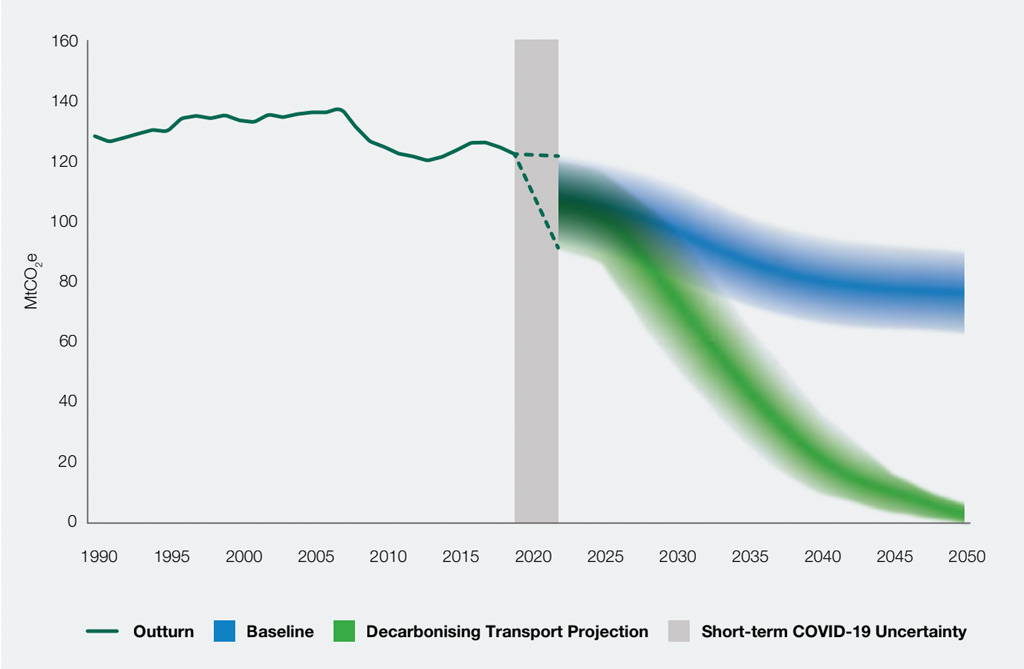

This pathway for the sector can be seen in the green curve below, compared to the blue one which represents existing government policies.

When international aviation and shipping are included, the sector does not reach net-zero by 2050. The remaining emissions would have to be offset elsewhere.

The width of the lines above indicate the uncertainty around this pathway, arising from potential changes in how people work and travel, technology change and Covid-19. The range of possibilities declines considerably as the green trajectory approaches 2050 due to the mass rollout of electric vehicles.

Responding to the new strategy, CCC chief economist Mike Thompson said that “the overall ambition…looks in line with our recommendations”.

Other important documents have been published alongside the main strategy, including consultations on ending the sale of “non-zero emissions” heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), regulating the phaseout of petrol and diesel cars and vans, and net-zero aviation by 2050.

There is also a “delivery plan” for the petrol and diesel phaseout, a response to a consultation on “smart” charging infrastructure and an environmental sustainability statement for railways.

How will the government encourage a switch to electric cars and vans?

The new strategy goes some way to explaining how the government will encourage the switch from combustion engines to battery vehicles in the UK, beyond the headline-grabbing targets.

Its overall vision, including previously announced policies, funding streams and targets, is set out in a “delivery plan” released alongside the main document.

Electric cars and vans deliver substantial emissions savings compared to their fossil-fuelled counterparts. What is more, CCC modelling suggests switching to more efficient electric vehicles will be essential for saving overall costs on the transition to a net-zero economy.

UK electric vehicle sales have increased rapidly in recent years. So far in 2021, pure electric vehicles have made up 8.1% of sales, up from 4.7% in 2020, according to figures from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT).

When hybrid vehicles are also included this figure goes up to 22.5% of car sales, compared to 13.7% last year.

This trend has gone hand-in-hand with car manufacturers lining up to make ambitious announcements about investing in electric vehicles and phasing out combustion engines.

Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares announces major electric investments:

— Peter Campbell (@Petercampbell1) July 8, 2021

⚡️€30bn by 2025 into electric & software

⚡️4 platforms, range of 300-500miles

⚡️40% US sales low-emission by 2030

⚡️70% EU sales low-emission by 2030

More to follow… (yes, this is going to be a thread) pic.twitter.com/WoSXj4U8O4

Nevertheless, there have been numerous warnings that more will be needed from the government to prepare the nation for 100% electric car sales.

In March, the government cut its plug-in car grant for electric vehicles from £3,000 to £2,500 and excluded models that cost more than £35,000, in a move that was criticised for sending inconsistent signals.

A report from the Public Accounts Committee emphasised the importance of “convincing consumers of the affordability and practicality of zero-emission cars, with up-front prices still too high for many in comparison to petrol or diesel equivalents”.

Meanwhile, another report from NGO Transport and Environment noted that there had been “no progress with a delivery plan to achieving the targets including stronger regulations on carmakers”.

A key component of the new strategy is a consultation on a zero-emission vehicle mandate for carmakers, something that the CCC has previously recommended.

Widely referred to as a “California-style” mandate due to its use in the US state, such a system would give manufacturers percentage targets for electric vehicle sales. They would earn credits for these sales and could meet their targets by purchasing excess credits from others who had overperformed.

This system is popular among various thinktanks and trade groups, who see it as an effective way of addressing growing consumer demand for electric cars.

Consultation on this announced today by DfT is a good step towards increasing supply of ZEVs to the UK. Waiting lists are ~6 months for many models, so we need to be addressing that and making it as easy to get a ZEV as it is to get an ICE vehicle. https://t.co/sjWKNySjUq

— Charles Wood (@EnergyCharles) July 14, 2021

It is also the “preferred option” in a consultation released with the main strategy, alongside regulations on vehicle CO2 emissions based on the framework that already exists.

The same consultation will also “seek to define” the “significant zero-emission capability” that all new cars and vans between 2030 to 2035 will have to deliver.

Currently, this loophole from the prime minister’s “10-point plan” will allow some hybrid vehicles to be sold during this period. The CCC has noted that this is “well after the 2032 date by which we recommend all such vehicles should be fully zero-emission”, and the definition “will be crucial” for keeping costs and emissions low.

The CCC has also said that a “coordinated national strategy” for electric vehicle charging infrastructure is needed to ensure facilities are widely available and evenly distributed.

It has recommended that 150,000 public charge points should be operating by 2025 and 280,000 by 2030. There are currently 20,800 public charge points across the UK.

The government already has some measures in place to improve this situation and says that later this year, it will publish a new strategy “setting out our vision for infrastructure rollout, and roles for the public and private sectors in achieving it”.

Other new commitments in the plan include a pledge to make the whole government fleet fully zero-emission by 2027, three years earlier than previously announced, and regulations coming later this year to ensure car-charging infrastructure is smart, “reducing costs for all bill payers”.

One omission from the strategy is clarity on how the government intends to make up the £37bn shortfall in lost fuel duty and other taxes when the UK car fleet switches entirely to electric models. The significance of this loss was emphasised in a report by the Office for Budget Responsibility last week.

Major new @OBR_UK report today on "fiscal risks" to UK has a big chapter on net-zero

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) July 6, 2021

OBR estimates net cost of net-zero by 2050 at £321bn

Crucially: "Unmitigated climate change would ultimately have catastrophic economic & fiscal consequences"

THREADhttps://t.co/GgKTivwu4S pic.twitter.com/lBqy5xhnpi

There have been calls for the government to replace the system with a pay-per-mile “road pricing” system, an idea that, when previously proposed by a Labour government, faced a backlash from motorists.

Instead of addressing this issue, the strategy repeats verbatim vague language from the 10-point plan about:

“[Ensuring} that the tax system encourages the uptake of electric vehicles and that revenue from motoring taxes keeps pace with this change.”

“I think they’re running scared of road-pricing to be honest,” transport policy advisor Stephen Joseph tells Carbon Brief. However, given the issue is “not going to go away”, he says it will most likely be dealt with in the much-anticipated Treasury net-zero review later this year.

In early July, the Times reported that the government was considering expanding the UK’s newly created emissions trading scheme (ETS) to include all transport, but that the prime minister was unwilling to increase the price of petrol for motorists. The new strategy does not reference this expansion, only mentioning the ETS in the context of aviation.

Finally, the strategy acknowledges that while their “lower bound” estimates for road-transport emissions reach zero by 2050, getting there may require more than is laid out in this plan.

People may hang onto their petrol and diesel cars for decades to come. This will be particularly damaging if they are high-polluting models, as researchers at the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions (CREDS) explained ahead of the strategy’s launch:

“If more and more of the highest-polluting petrol and diesel powered SUVs and high-end cars enter the market until they are banned from sale in 2030, they will lock-in an enormous amount of fossil fuel into the transport system way into the 2040s.”

The significant rise in UK SUV sales in recent years has cancelled out any emissions gains from switching to electric vehicles. Despite this, these vehicles are only mentioned once in the 220-page strategy.

However, it does note that in the future “additional targeted action” – such as “steps to reduce use of the most polluting cars and tackle urban congestion” – may be required to meet climate targets. Another transport decarbonisation plan in five years’ time will assess progress.

What are the new plans for decarbonising trucks, buses and motorbikes?

A key pledge from the new strategy, which was the focus of several news outlets, is the government’s intention to phase out petrol and diesel heavy goods vehicle (HGV) sales by 2040, pending a consultation.

The plan would see smaller trucks banned by 2035 and larger vehicles weighing more than 26 tonnes going the same way by 2040. However, the government says this could be earlier, “if a faster transition seems feasible”.

This is in line with CCC advice, which suggests a net-zero compatible pathway will see zero-emission HGVs reaching “nearly 100% of sales by 2040”.

However, it has been dismissed as “unrealistic” by trade body the Road Haulage Association, which claims that such vehicles “don’t yet exist”.

In the consultation on zero-emission HGVs released alongside the strategy, the government says that there are plans and legislation in place to address this.

It adds that they are investing £20m this year in planning zero-emission road freight trials, which will cover hydrogen-powered trucks, batteries and “electric road” systems in which vehicles are powered by overhead lines.

The CCC has emphasised the importance of “large-scale” trials in the early 2020s to establish the best-fit technology, with decisions being made in the second half of the decade.

Besides this, the government also lays out plans that could result in the remaining petrol and diesel road transport fleet also being phased out. It has begun consulting on a phaseout for buses and plans to do the same for coaches.

Subject to another consultation, there is also a plan to ensure all new motorbikes sold from 2035 are zero-emission models.

The accompanying press release describes the overall pledge to “phase out all polluting road vehicles within the next two decades” as “world leading”, a favourite phrase of the government when describing its climate policies.

What does the strategy say about cutting traffic and road building?

Prof Jillian Anable, a transport researcher at the University of Leeds, told an Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) event in June that there were issues with government’s singular focus on electric vehicles:

“It’s been the only egg in the transport decarbonisation basket for some time…but the focus is delusional.”

Even if all combustion engine car sales end, various modelling exercises have demonstrated that car traffic will need to drop 2-4% each year over the next decade to align with net-zero.

This is because many of the cars still being sold in the coming years will likely be hybrids that largely still run on fossil fuels, and even after the ban petrol and diesel cars will remain on UK roads for years to come. The average scrappage age for cars has been increasing steadily for years.

Also, with lorries, trains and planes decarbonising later, cars will need to overcompensate for emissions cuts in the short term, according to Anable. She tells Carbon Brief:

“You simply cannot achieve any emissions reductions from the transport sector by 2030 if traffic growth is allowed to continue, and [you] need significant absolute reductions from today’s levels in order to make any real cuts in carbon.”

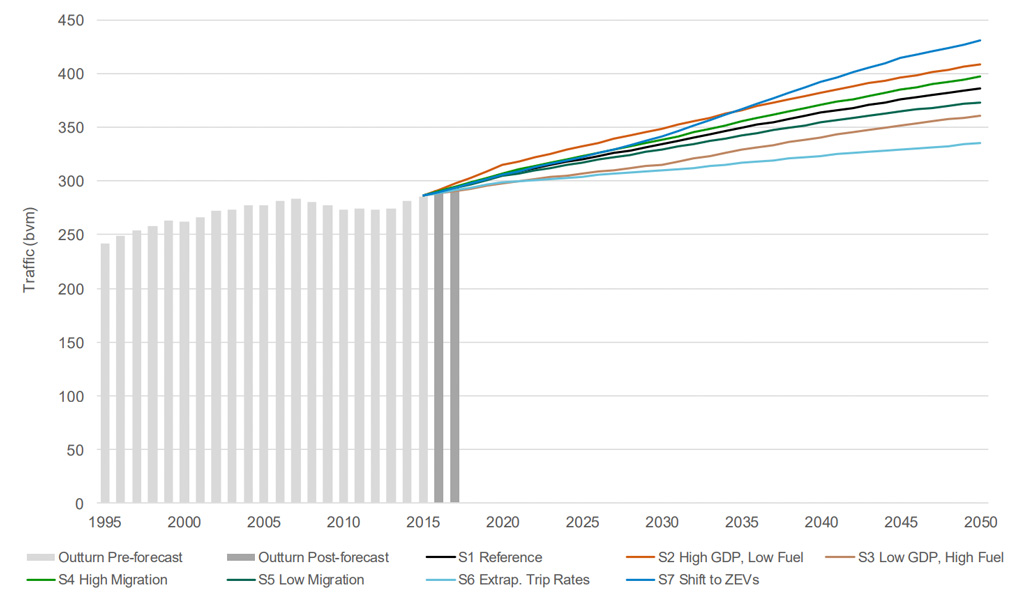

As the chart below shows, the Department for Transport anticipates a steady increase in traffic in the coming years, and one that will only accelerate as the switch to electric vehicles makes driving significantly cheaper than public transport.

Indeed, the government scenario where 100% of cars and vans are electrified by 2050 also results in the highest level of traffic growth out of all seven scenarios.

Cutting traffic is not a centrepiece of the strategy. A statement released by transport secretary Grant Shapps explains that the new plan “is not about stopping people doing things: it’s about doing the same things differently…We will still drive on improved roads, but increasingly in zero-emission cars”.

Nevertheless, there are hints in the plan that the government intends to take some action to address traffic, particularly through its measures to improve walking and cycling infrastructure (see: Are there any plans to support public transport, walking and cycling?).

The plan explicitly states that “we want less motor traffic in urban areas” and says the aim is for 50% of all trips in towns and cities to be on foot or by bike by 2030.

Prof Phil Goodwin, an emeritus professor of transport policy at University College London, tells Carbon Brief that the combined effect of the ambitions set out in the government’s plan would be to “reduce traffic below previous forecasts, or absolutely, or both”.

However, he adds that there are no specific policy measures – such as traffic and parking restrictions in cities – that would help achieve this.

Meanwhile, the government is still pursuing its £27bn road-building plans, which are currently the subject of a court case by campaigners who say the scheme does not align with the government’s climate goals.

Transport decarbonisation will need different infrastructure plans, starting with reappraisal of all the schemes in the current road programme. None of them have been assessed using methods which consider the impacts of climate change or of policies to deal with it.

— Phil Goodwin (@Phil_Goodwin99) July 13, 2021

“After this plan, [the road building programme] is even odder, even more out of kilter,” Joseph tells Carbon Brief. Research suggests that new roads lead to more, rather than less, traffic.

While the strategy defends the government’s road-building plans, it also pledges to review its National Networks National Policy Statement (NNPS), which sets the policy for roads and was written in 2014, long before the net-zero target was set.

“It is right that we review it in the light of these developments, and update forecasts on which it is based to reflect more recent, post-pandemic conditions,” the plan states.

However, Goodwin says that it is “entirely illogical and inconsistent” that the government would review the statement, but not individual road plans that come under it. “For most of the schemes the reasons for reviewing them are exactly the same as the reasons for reviewing the NNPS,” he tells Carbon Brief.

Joseph adds that with Highways England – which maintains and operates major roads – mentioned just once in the document, he feels they have “been given a complete free pass”, with no obligation to participate in the net-zero transition.

Are there any plans to support public transport, walking and cycling?

In a decarbonising transport consultation released in March 2020, Shapps said that public transport and active travel should become the “natural first choice for our daily activities”, based on a “convenient, cost-effective and coherent public transport network”.

This rhetoric is repeated throughout the new strategy document, and “accelerating [a] modal shift to public and active transport” is the first of six “priorities” it identifies.

Yet there are few in the way of new commitments on this topic, with a rehash of a pledge from last year to spend £2bn on walking and cycling routes and other measures to boost uptake. Government priorities have previously been set out in a document titled “gear change”.

The strategy also repeats a plan to spend £3bn on buses in England outside London and deliver 4,000 zero-emission buses. It recognises the need to encourage bus use following a pronounced drop in demand that began during the Covid-19 lockdown.

Critics have been quick to compare this £5bn in spending to the £27bn set aside for road building.

However, there is a suggestion that more is on the way, with the plan emphasising that active travel offers “high value for money” and a note that “further announcements on cycling and walking will be made later this summer”.

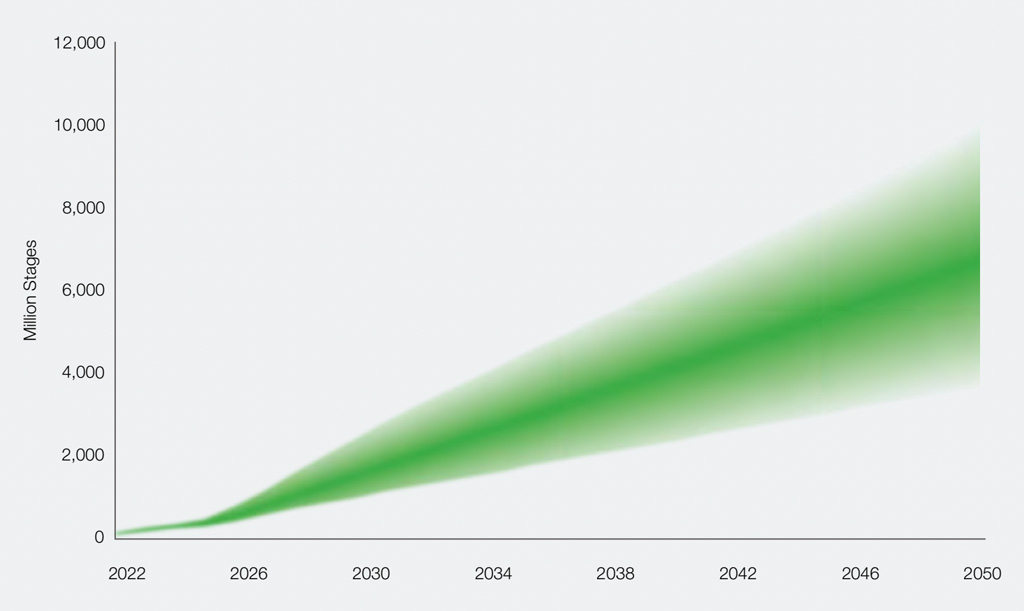

The chart below shows the potential range of future cycling and walking growth, depending on “future investment and scale of behaviour change”, according to government estimates. It says that these activities could cut car emissions between 1-6m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) by 2050.

One area of public transport that receives more attention in the strategy is the UK’s rail network. There is a pledge to deliver a net-zero network by 2050, “with sustained carbon reductions in rail along the way”.

It notes that while electrification of the railways is “likely to be the main way of decarbonising”, the government will also consider battery and hydrogen trains, which may be more cost-effective on lines that are used less.

There is also an ambition to remove all diesel-only trains from the freight and passenger network by 2040 and a “rail environment policy statement” alongside the main document.

However, amidst the discussions of making rail travel greener, there is very little on convincing people to use the train instead of other, dirtier forms of transport. On the day of the strategy’s launch, consumer group Which? published analysis showing that popular UK train routes are 50% more expensive than the equivalent airline fares.

What are the plans for aviation and shipping?

There are a handful of announcements in the strategy concerning some of the highest-emitting forms of transport, aviation and shipping.

While domestically these sectors only contribute 7.5% of emissions, the UK’s portion of international emissions, when included, increases the total from around 120MtCO2e to around 170MtCO2e as of 2019.

Beyond an overarching goal to make all UK aviation net-zero by 2050, the plan brings forward the date for net-zero domestic flights to 2040.

However, despite these big targets, the overall message of the plan was that people could “carry on flying”, as a BBC News headline put it.

“There’s no demand management there,” Joseph tells Carbon Brief, noting that this was in spite of frequent-flyer levies being available as potential fair solutions to growing demand.

In its recent progress report, the CCC highlighted aviation demand as a key area in which government policies diverged from the committee’s recommendations.

“Government must recognise the need for demand management as part of a wider strategy to decarbonise aviation,” it notes.

Airline passenger numbers rose 36% between 2009 and 2019, and emissions rose 7% as fuel efficiency improvements were not enough to offset demand. While Covid-19 may suppress flights for the time being, they are ultimately expected to recover.

The CCC has also highlighted as a key “gap that must be addressed” the “overdue” net-zero aviation strategy, which it says should also include an assessment of the UK’s airport

capacity strategy. This comes after lengthy legal challenges on climate grounds over the decision to expand Heathrow airport.

Alongside the new strategy, the government has released a consultation on “jet-zero”, its draft net-zero aviation plan.

The plan contains no indication that the government intends to curb demand or reassess its airport capacity. “We want to preserve the ability for people to fly whilst supporting consumers to make sustainable travel choices,” it states.

Instead there is a focus on technological solutions including zero-emission aircraft, sustainable fuels and carbon-offsetting markets.

Progress on shipping is slower, with only a promise to “plot a course to net-zero for the UK domestic maritime sector, with indicative targets from 2030 and net-zero as early as is feasible”. There will be a consultation on this in 2022.

And very little on shipping. Perhaps we need an equivalent to the “Jet Zero” aviation council – DfT like a pun, so “Wet Zero” has to be a contender.

— Tim Lord (@timbolord) July 14, 2021

There are also plans for a potential phaseout date for the sale of fossil fuel-powered domestic vessels, to mirror the ones being introduced for road vehicles.

-

In-depth Q&A: What is the UK’s ‘net-zero’ plan for transport?

-

In-depth Q&A: What is the UK’s plan for making its transport ‘net-zero’?