Mat Hope

10.12.2014 | 12:01amInvesting in low carbon energy generation could lower future household energy bills and insulate the economy from volatile fossil fuel prices, the government’s official climate change advisor says. But only if the government commits to implementing long-term climate policies.

A new report from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) assesses the impact of the UK’s low carbon policies on consumer energy bills. It expects households to pay more to decarbonise the UK’s energy sector in the coming decades, but says that doing so should ultimately save people money as well as helping the UK hit its legally binding climate goals.

The committee’s conclusion mirrors that of government analysis earlier this month that showed energy bills would rise significantly if the UK fails to implement climate policies.

Bill projections

The government is legally obligated to cut the UK’s emissions, the committee points out. Some policies to cut emissions are paid for by households through a levy on their energy bills. While such levies are set to increase, decarbonisation should lower electricity prices in the long run and cut demand, meaning households save money overall, the committee says.

The Climate Change Act of 2008 requires the government to cut emissions 80 per cent by 2050. With about 35 per cent of the UK’s emissions currently coming from the energy sector, that means some pretty significant changes to how the country generates electricity.

The government incentivises companies to build more renewables, nuclear and carbon capture and storage technology by offering subsidies through mechanisms such as feed-in tariffs or contracts for difference. It can also implement policies to bolster the carbon price, making fossil fuel electricity generation more expensive.

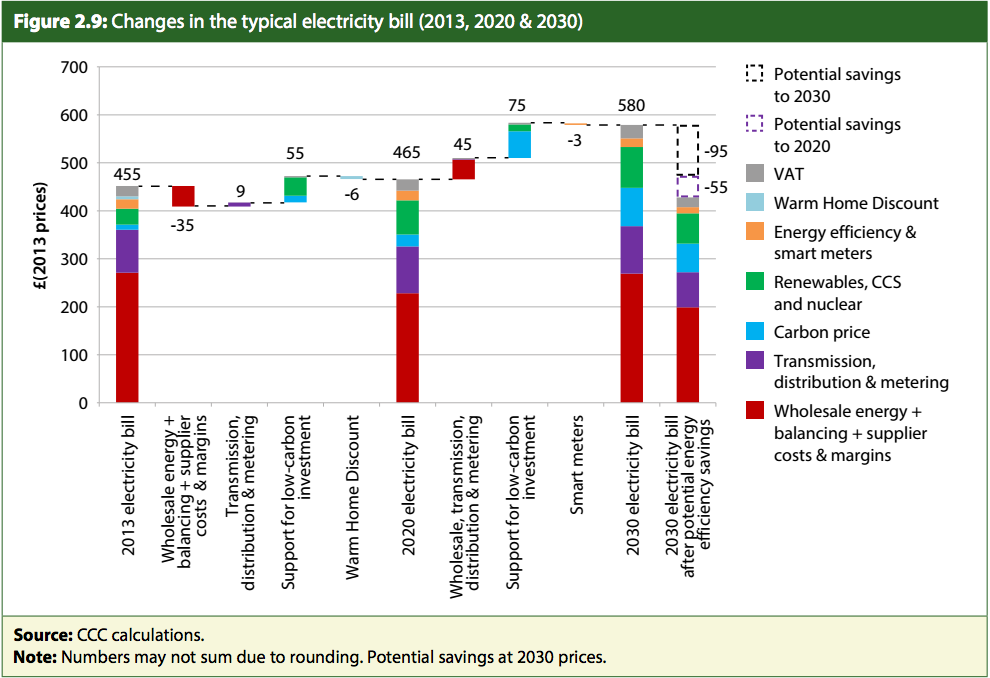

This graph shows how the committee expects household energy bills to rise up to 2030, to pay for the policies. The solid bars show how much a household may pay for each policy under the CCC’s central scenario. The dotted boxes show how much they may save as a consequence of the policies.

An average household on a dual fuel tariff could be paying about £130 more to support decarbonisation in 2030 than today, the committee projects. But the additional cost could be more than offset by the money households save by using less energy and indirectly paying less for gas power as a consequence of the policies.

Energy efficiency policies could save an average household on a dual fuel tariff £210 compared to today, the committee estimates. The savings are even greater if gas prices rise, and the government implements policies to ensure a strong carbon price.

Delivering savings

While the costs of supporting the government’s decarbonisation policies are likely to increase, the government needs to improve certain areas of its climate policy if households are going to see the savings, the committee says.

The most significant improvements need to be made around the UK’s energy efficiency policies, according to the committee. For instance, the government needs to ensure all lofts and cavity walls in the UK’s homes are insulated by 2022, with another 3.5 million solid walls insulated by 2030.

The committee says the government’s current budget of £1.4 billion for such measures would be enough to deliver this. But that budget is set to be cut by £600 million, which puts the policies at risk.

The government also needs to ensure there is a strong carbon price, the CCC says. A strong carbon price makes fossil fuel power more expensive, and should accelerate the switch to renewables.

The UK’s carbon price floor effectively tops-up the EU’s carbon price, which has slumped to record lows in recent years. The policy is designed to ensure fossil fuel power generators pay a minimum of £7 for every tonne of carbon dioxide they emit in 2013, rising to £23 in 2020 and £76 in 2030.

But the policy is under threat. The government earlier this year froze the carbon price floor at 2014 levels until 2020. It is unpopular with industry and environmental NGOs alike, which see it as an inefficient way to cut emissions. That means the Conservatives may see it as the most plausible green levy to cut in the run up to next year’s election.

But decarbonising the UK’s energy sector has other benefits the government may be interested in, the committee says. Supporting low carbon energy technologies can protect the UK from volatile gas prices, which the government predicts will rise between 2020 and 2030. If the government invests in renewables now, it means there will be more cheap, low carbon electricity available in the coming decades, restricting the impact of rising gas prices on household energy bills.

Uncertainty

Such scenarios are far from certain, however, and the committee sounds a note of caution about putting too much faith in specific estimates.

“There is considerable uncertainty around these projections, particularly relating to gas and carbon prices, and the costs and deployability of low-carbon technologies,” it says. Changes in the gas price could mean the government spends up to £6 billion more or less on low carbon support. Carbon price changes could affect the projections to the tune of £4 billion.

Nevertheless, the committee’s report fits with government’s own analysis that climate policies don’t just have the potential to cut emissions, they could lower household energy bills, too. That might seem counter-intuitive given the current dynamic around bills, but it reflects how different the energy system will be if the government’s decarbonisation project succeeds.