Media reaction: What Joe Biden’s landmark climate bill means for climate change

Multiple Authors

08.17.22Multiple Authors

17.08.2022 | 5:00pmOn Tuesday 16 August, US president Joe Biden signed a bill into law that he has described as “the most significant legislation in history to tackle the climate crisis”.

The Inflation Reduction Act contains $437bn of spending, $369bn of which will go towards emissions-cutting measures such as tax breaks for low-carbon energy and electric vehicles.

It was agreed after months of haggling with Democrat Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, a coal “baron” who has repeatedly sunk Biden’s attempts to pass ambitious climate legislation. No Republicans supported the bill.

In terms of the money committed, the bill is still far off the scale of the earlier proposals put forward by the administration when Biden took power back in 2021. It also includes some provisions to expand oil-and-gas drilling on public lands.

Nevertheless, it brings the US much closer to meeting its international climate targets. There has also been broad agreement that, despite its shortcomings, the bill marks the most ambitious climate action ever taken by Congress.

In this article, Carbon Brief explores the contents of the bill, the impact it is expected to have on US emissions and how the media has responded.

- How has the Inflation Reduction Act come about?

- What climate and energy measures does the bill contain?

- How much will it cut US emissions?

- How does it differ from Biden’s previous proposals for climate legislation?

- How has the media responded?

How has the Inflation Reduction Act come about?

Prof Jesse Jenkins, an energy researcher at Princeton University, told ABC News the bill marked “the first substantive piece of climate legislation that has made it through the US Senate in history, after decades of inaction”.

Previous efforts to pass climate legislation have been scuttled, often by the Republican party, according to a piece in the New York Times that detailed the history of attempted climate legislation. The paper added that the new bill “replaced the sticks with carrots” – using subsidies, rather than carbon taxes, to address climate change.

The Atlantic pointed out that “Republican-led climate efforts have also failed to bear fruit” in Congress, with the party’s support restricted to “smaller, more incremental bills”.

As a result, US climate action at the federal level has largely relied on executive actions, which can easily be undone by successive presidents.

Previous administrations have relied on the Clean Air Act – a statute on air pollutants administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) – to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. However, these powers were curtailed by the US Supreme Court in a June ruling.

Just weeks before the Inflation Reduction Act was announced, Manchin had seemingly scuttled the Democrats’ climate agenda, the Washington Post reported at the time. The paper says he told party leadership that he “would not support an economic package this month that contains new spending on climate change or new tax increases targeting wealthy individuals and corporations”.

The continued negotiation of the bill was “Washington’s best-kept secret”, Politico wrote, as Manchin and senate majority leader Chuck Schumer “quietly continued negotiating behind the scenes, mostly through staff”.

In the weeks leading up to the introduction of the bill, Biden had come under increasing pressure to declare a “climate emergency” – “one of the few presidential powers that can be exercised without much oversight from Congress or the courts”, the New York Times explained.

Then, on the evening of 27 July, Schumer and Manchin issued a joint statement announcing that they had reached agreement on a “spending package that aims to lower health-care costs, combat climate change and reduce the federal deficit”, reported the Washington Post.

The agreement – which marked a “massive potential breakthrough for President Biden’s long-stalled economic agenda” – capped off “months of fierce debate, delay and acrimony, a level of infighting that some Democrats saw as detrimental to their political fate ahead of this fall’s critical elections”, said the paper. A one-page summary (pdf) of the bill explained that it would see investment of $369bn for “energy security and climate change”.

In response to the surprise announcement, Tiernan Sittenfeld, senior vice president of government affairs of the environmental advocacy group the League of Conservation Voters, said to Politico:

“Holy shit…This deal is coming not a moment too soon.”

The bill immediately faced criticism. Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell described it as a package of “job-killing tax hikes, Green New Deal craziness”. Democrat senator Bernie Sanders, chair of the Senate budget committee, warned that it went “nowhere near enough” on a number of fronts.

Despite making several unsuccessful attempts to amend the bill – including to “remove oil and gas handouts”, reported Common Dreams – Sanders nonetheless said it was “an important step forward” and so he was “happy to support it”.

Today the Inflation Reduction Act passed the Senate 51-50. In my view, this legislation goes nowhere near far enough for working families, but it does begin to address the existential crisis of climate change. It’s an important step forward and I was happy to support it. pic.twitter.com/x27lx2FFiJ

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) August 7, 2022

Passing legislation through the US Senate typically requires 60 votes, but this bill was introduced under “reconciliation” – a budgetary process that needs only a simple majority for approval. With the Senate evenly split between Democrats and Republicans, US vice-president Kamala Harris cast the deciding vote to break the deadlock.

The reconciliation process allows Congress to “quickly advance high-priority fiscal legislation”, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a US-based thinktank. It covers “certain tax, spending and debt limit legislation”, and has “real advantages for enacting controversial budget and tax measures”, the CBPP says.

The bill was initially presented by senators Manchin and Schumer, and there was uncertainty among the party whether or not Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema – “the other big holdout in the Senate on Build Back Better” – would support the bill, Vox reported.

Sinema is “like Manchin, a maverick in the caucus”, Reuters wrote.

The newswire reported: “without Sinema’s vote the entire effort could be doomed, as no Republicans were expected to vote yes” on the bill. Sinema ultimately agreed to “move forward” with the legislation the week following its announcement, Reuters reported in a separate piece.

The Senate approved the bill on 7 August, with Senator Brian Schatz, a Democrat from Hawaii, reportedly crying “tears of joy as he left the chamber”, said BBC News. The broadcaster quoted Schatz saying:

“Now I can look my kid in the eye and say we’re really doing something about the climate.”

With agreement in the Senate, the bill then passed to the House, where is was given final approval on 12 August, reported the New York Times:

“With a party-line vote of 220 to 207, the House agreed to the single largest federal investment in the fight against climate change and the most substantial changes to national health care policy since passage of the Affordable Care Act. The bill now goes to [President] Biden for his signature.”

House speaker Nancy Pelosi said it was “really a glorious day for us”, adding that “this legislation is historic, it’s transformative and it is really a cause for celebration”, the paper reported. Democrats “erupted in raucous applause as soon as they reached the votes required for passage”, said the Washington Post in a frontpage story.

In this historic moment, I want to thank Congressional Democrats for supporting the Inflation Reduction Act.

— President Biden (@POTUS) August 12, 2022

It required many compromises. Doing important things almost always does. I look forward to signing it into law. pic.twitter.com/S1WmyTSOBM

The Atlantic noted that “perhaps the most important number about the package is zero” – the number of Republican members of Congress, in both houses, that voted for the bill.

President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law on 16 August, noting that it was something he had looked forward to doing for 18 months, reported the Washington Post. In its coverage of the signing of the “landmark bill”, the Guardian reported the comments of Biden, who said:

“This bill is the biggest step forward on climate ever…It’s going to allow us to boldly take additional steps toward meeting all of my climate goals, the ones we set out when we ran.”

This is a BFD. https://t.co/L0sh8ULo4T

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) August 16, 2022

The Independent added that the signing ceremony “will be followed by a larger celebration on 6 September”.

Biden hands Joe Manchin the pen he used to sign the Inflation Reduction Act. (Drew Angerer/Getty) pic.twitter.com/aHEKq4xbcW

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) August 16, 2022

Following the signing, Bloomberg reported on the “secret push” to save the bill that “billionaire philanthropist and clean-energy investor” Bill Gates had been undertaking, starting before President Joe Biden had won the White House. It said:

“Gates started wooing Manchin and other senators who might prove pivotal for clean-energy policy in 2019 over a meal in Washington DC. ‘My dialogue with Joe has been going on for quite a while,’ Gates said. ‘Almost everyone on the energy committee’ – of which Manchin was then the senior-most Democrat – ‘came over and spent a few hours with me over dinner’.”

On the bill’s “counterintuitive” name, Bloomberg wrote: “today’s political and media landscape demands that legislation be packaged to steer public debate”. With inflation “a pressing worry” across the US, “it’s not surprising that the word won out” over more explicit references to climate change, the outlet added.

Prof Ed Maibach, the director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication, told Bloomberg that “calling the bill the Inflation Reduction Act was a stroke of rhetorical genius”. Prof Leah Stokes, a political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara who advised Democrats on the bill, told the outlet:

“Focusing on health and jobs is a more powerful rhetorical technique than [highlighting] climate…But that may be changing.”

What climate and energy measures does the bill contain?

In total, the act contains $437bn of “investments” including tax credits by the federal government, of which $369bn will go towards what the bill describes as “energy security and climate change”.

On top of this, it sets aside an additional $4bn for “western drought resiliency”. Bloomberg reported that this measure followed pressure from a group of senators, led by Sinema, based in western US states that are feeling the effects of droughts.

In total, 85% of the investment in the Inflation Reduction Act will go towards either cutting emissions or addressing the impacts of climate change. The remainder will go towards an extension of the Affordable Care Act.

Both the climate and health provisions in the bill are set to be paid for by new measures that increase taxes on large corporations and curb tax avoidance, according to the Hill.

These include what the news website referred to as the “centrepiece” of the tax strategy – a 15% minimum tax on corporations, expected to raise $222bn over the next decade.

(This is supposed to implement an OECD minimum corporate tax rate, but according to the Financial Times “leaves gaps that mean [it] is not in line with [the] global deal”.)

These include what the new website referred to as the “centrepiece” of the tax strategy – a 15% minimum tax on big corporations, which is expected to raise $222bn over the next decade.

The bill’s measures to boost energy security and curb emissions primarily consist of a series of grants, loans, tax credits and emissions charges for low-carbon electricity supplies and electric vehicles.

Low-carbon energy

The Biden administration has a target of reaching a “carbon pollution-free” power sector by 2035. According to analysis by the Rhodium Group thinktank, the Inflation Reduction Act puts the US in a “strong position” to meet this goal.

The analysis estimates that the share of US electricity generated by renewables and nuclear could roughly double, from 40% in 2021 to 60-81% in 2030, due to measures in the new bill.

This would involve annual renewable capacity growth roughly doubling from current levels out to 2030, Rhodium said, as well as preventing 10-20 gigawatts (GW) of nuclear power from retiring.

With the Inflation Reduction Act, more than double the amount of wind turbines will be spinning in 2030 – turbocharging America’s clean energy future. pic.twitter.com/OSLf3UAOYq

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) August 11, 2022

The bill extends wind and solar tax credits by 10 years and extends similar incentives to battery storage and biogas. It also includes new or extended tax credits for nuclear power, clean hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The inclusion of CCS was criticised in a frontpage comment article for the New York Times, which said subsidies for these technologies were a “counterproductive waste of money, backed by the fossil fuel industry”.

On the other hand, Prof Wil Burns, who co-founded the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy at American University, wrote in the Conversation that the provisions in the bill would not be sufficient to scale up the technology over the next decade.

Further tax credits go to support domestic production and infrastructure needed for “sustainable aviation fuels” and other biofuels.

According to Senate Democrats, the bill contains “roughly $30bn in targeted grant and loan programs for states and electric utilities to accelerate the transition to clean electricity”.

Finally, there is $27bn set aside for a “clean energy technology accelerator”, also referred to as a “national green bank”, to support the deployment of clean technologies, particularly in disadvantaged areas. Inside Climate News explained that this was a “big deal”, with the potential to significantly scale up private investment in technologies such as heat pumps.

Low-emissions technologies for households

There are also incentives for people to encourage uptake of low-carbon technologies for their homes, including 10 years of consumer tax credits for energy efficiency upgrades and the installation of heat pumps and rooftop solar power.

There is also $9bn in home energy rebates to electrify home appliances and retrofit houses, which will focus on low-income households, as well as an additional $1bn grant program to make affordable housing more energy efficient.

A key selling point of the act touted by Biden and the Democrats is that it will lower energy costs for US citizens.

Rhodium Group analysis backs this claim, suggesting that the provisions of the act would mean household energy costs being up to $112 lower on average in 2030, than they would have been without the legislation.

The Inflation Reduction Act will position America to meet my climate goals, saving families hundreds of dollars a year on energy costs.

— President Biden (@POTUS) August 16, 2022

And for families that take advantage of clean energy and electric vehicle tax credits – they could see more than twice the savings.

Electric vehicles

The bill also contains tax credits to encourage people to purchase low-emissions vehicles.

Specifically, there is a $4,000 tax credit for low- and middle-income people who want to buy a used electric car, and $7,500 for those who want to buy a new vehicle, until 2032.

It also eliminates the 200,000 vehicle sales cap for tax credits, which previously meant manufacturers would no longer be eligible to sell their cars using the incentive once they had exceeded that limit. Electric vehicle news outlet Electrek noted that firms such as Tesla and GM surpassed this limit “years ago”.

These measures do come with stipulations intended to restrict the cars being purchased to exclude minerals and components from certain countries, notably China, which as Time reported currently provides the “vast majority” of these items to the US.

Also—and this might be burying the lede a bit—there are restrictions against ANY battery metals or components from “entities of concern.” I *believe* that includes China—though haven’t seen latest list.

— Tom Randall (@tsrandall) July 28, 2022

Battery manufacturing/assembly restriction begins 2024, materials in 2025 6/

The magazine added that there are also price restrictions, meaning that cars costing more than $55,000 will not be eligible for the credits. Only 15 models currently sold in the US meet this price restriction, and their manufacturers will need to make changes to conform to the additional “made-in-North America battery sourcing requirements”, it stated.

In addition, the bill sets aside $3bn for the US Postal Service to purchase zero-emission vehicles. It also includes $1bn for low-carbon heavy-duty vehicles, including buses and garbage trucks.

Fossil fuels

Much has been made by environmental groups of parts of the act that could boost production of oil and gas on public lands and waters.

These measures were reportedly introduced to secure Manchin’s support and led to the bill being dubbed a “devil’s bargain” by writers in the Guardian, New Republic and Mother Jones.

First, the bill requires the sale of four offshore oil-and-gas leases that were previously struck down by courts or executive orders on environmental grounds.

This includes the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline, a gas pipeline that passes through Manchin’s home state of West Virginia. Mountain State Spotlight described this provision as the senator’s “price for supporting the climate change bill”.

Second, Atmos reported that the bill requires any further offshore wind lease sales to come only after the government has held oil-and-gas lease sales on at least 60m acres. This particular element “has left climate justice advocates with mixed emotions over its passage through the Senate”, the piece added.

These provisions go against Biden’s pledge on his first day in office to end new oil-and-gas drilling on federal lands. In addition, the International Energy Agency (IEA) found that no new fossil fuel investment would be needed if the world follows a pathway to net-zero emissions by 2050.

At the same time, the act also includes several provisions that could curb emissions from the fossil fuel industry and hold back future production.

It includes a methane emissions reduction programme to cut leaks from the production and distribution of gas, with grants and loans for producers and fees applied to those emitting too much. There is also additional funding of $1.6bn to monitor methane leaks.

More broadly, the bill includes increases to the royalty rates paid by companies that want to extract oil and gas from public lands and waters.

Industry and manufacturing

The bill has a big focus on support for domestic manufacturing of low-carbon technologies, with more than $60bn set aside to establish and maintain these industries within the nation’s borders.

This includes around $30bn in production tax credits for solar panel, wind turbine, battery and critical mineral companies, as well as $10bn in investment tax credits to build new manufacturing facilities.

For electric car manufacturing, the bill contains up to $20bn in loans to build new facilities and $2bn to re-tool existing facilities to build low-emissions vehicles.

The bill contains $9bn to allow federal procurement of “American-made clean technologies” that will help to provide a stable market for these products.

There is also $500m to carry out programmes authorised by the Defense Production Act – a Korean War-era law that gives presidents the power to direct private companies during national emergencies. This was recently invoked by Biden to speed up manufacturing of key technologies including heat pumps.

In order to boost emissions reductions from heavy industry, one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise, there is $6bn for a new “Advanced Industrial Facilities Deployment Programme”, which will help fund improvements to energy efficiency, among other things.

Finally, there is $2bn in funding for the US network of national labs to “accelerate breakthrough energy research”.

Environmental justice

The bill includes unprecedented funding for disadvantaged communities that are disproportionately affected by pollution and climate impacts, according to Senate Democrats, totalling $60bn for “environmental justice priorities”.

Nevertheless, the environmental justice community has pushed back against the proposals, according to Inside Climate News, noting that the earlier failed Build Back Better bill contained an additional $100bn in funding for such measures (see: How does it differ from Biden’s previous proposals for climate legislation?).

Among the funding streams available under the act are $3bn in “environmental and climate justice block grants”, which local governments, Native American tribes and community groups can access to tackle environmental issues in their areas.

There are also $3bn worth of “neighbourhood access and equity grants”, primarily to improve affordable transportation access and reconnect communities that have been divided by highways. A further $3bn will be handed out to improve air quality at ports by paying for zero-emissions equipment.

Agriculture and land

There are also various funding streams targeting farming and nature restoration projects, notably $20bn to support climate-smart agriculture practices.

Vox reported that this “could help blunt” some of the harmful environmental impacts of farming, including measures to “help farmers create more habitat for pollinators like bees, store more carbon in the soil and make farms more resilient in the face of extreme weather”.

Finally, the bill also includes $5bn in grants to support fire-resilient forests, forest conservation and urban tree planting, and $2.6bn in grants to conserve and restore coastal habitats.

How much will it cut US emissions?

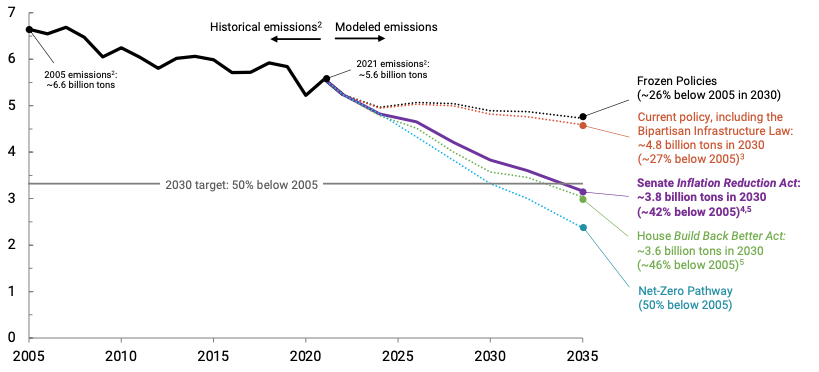

The Inflation Reduction Act would result in emissions being around 42% lower than 2005 levels by 2030, according to analysis by the REPEAT Project, based at Princeton University. This is in line with the 40% reduction quoted by Democrat senators.

Other assessments gave a range of estimates, with the Rhodium Group concluding it would result in emissions 32-42% below 2005 levels in 2030 and Energy Innovation putting the reduction at 37-41%.

In its analysis, Rhodium Group notes that the range reflected “uncertainty around economic growth, clean technology costs and fossil fuel prices”.

More action across all levels of government would still be needed to reduce emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels, which is the US’ international target under the Paris Agreement.

Nevertheless, as the REPEAT Project chart below shows, the Inflation Reduction Act (purple) is a considerable improvement on the current policy landscape (red).

Even when accounting for the climate provisions in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which Biden managed to pass towards the end of 2021, the US had only been on track to cut emissions by 27% from 2005 levels – barely halfway towards its climate target.

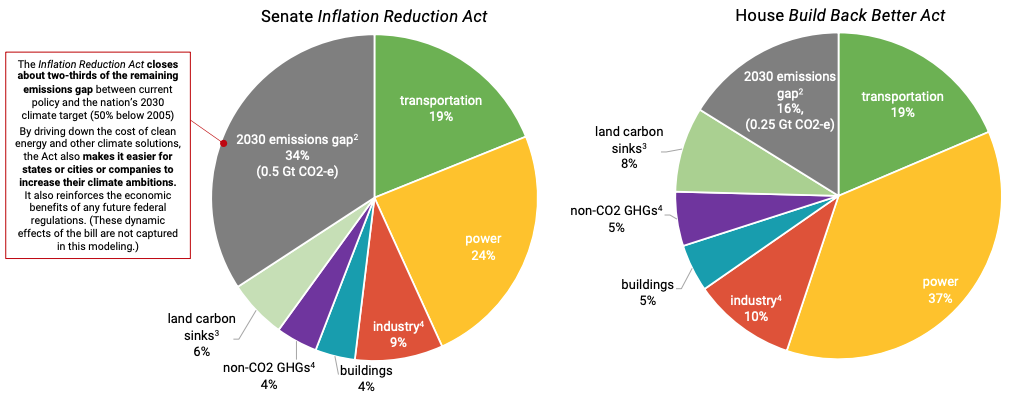

In total, the REPEAT Project assessment concludes that the new bill closes around two-thirds of the gap between current policy and the 2030 climate goal. It also suggests the bill comes close to the emissions impact of the Build Back Better plan.

While much has been made of the provisions made for new oil and gas production in the bill, the analysts largely downplayed the impact this would have on the US emissions trajectory.

To emphasise this, Energy Innovation noted that for every tonne of emissions potentially resulting from these provisions, 24 tonnes would be avoided by other measures in the bill.

However, a more pessimistic outlook was released by Climate Action Tracker (CAT) on the day the bill was signed into law by Biden. It places greater emphasis on the fossil fuel support included in the document and estimates a wider potential range of emissions cuts by 2030 – between 26 and 42% below 2005 levels.

The US is still some way from its 2030 target, and the compromise to re-open public lands for oil & gas prodn cld delay decarbonisation – or lead to stranded assets. Finance remains Critically Insufficient.

— ClimateActionTracker (@climateactiontr) August 16, 2022

For full policy breakdown https://t.co/m77AzniTFk /4 pic.twitter.com/k124YBIQW6

CAT notes that there is “high uncertainty about the outcome of the Inflation Reduction Act and its implementation” and says that previous short-term actions by Biden to deal with high oil-and-gas prices, such as encouraging fossil fuel producers to increase drilling, “may compromise his long-term climate goals”.

Associated Press quoted the director of CAT developer Climate Analytics, Bill Hare, who told the publication that despite its shortcomings the bill should reduce future global warming “not a lot, but not insignificantly either”.

Climate Home News quoted US climate envoy John Kerry, who said:

“I am hopeful that it will prompt all major economies to define and deliver on 2030 emission reduction targets that keep a safer 1.5C future within reach.”

However, the news website also says this ambition may be hampered by what the CAT analysis describes as the “critically insufficient” provision of climate finance by the US, something the nation has pledged to provide to developing countries as part of its international climate obligations.

Biden promised to provide $11.4bn a year in climate finance by 2024, but last year Congress approved just $1bn. Without more finance, other nations are expected to be less willing to increase their own emissions cuts.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, CAT describes the US’ climate policies and pledges as “insufficient” for achieving the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C temperature limit.

How does it differ from Biden’s previous proposals for climate legislation?

The Guardian noted that the spending package is “substantially smaller” than the original $3.5tn Build Back Better Act that Biden proposed last year, which was passed by the House in November 2021 but not taken up in the Senate after Manchin pulled his support.

The New York Times wrote that the legislation “falls far short of the transformational cradle-to-grave social safety net plan” that Biden initially lobbied for, adding that “many of those elements were dropped as Democrats contended with the realities of their slim majorities in Congress”.

The initial proposal “included the establishment of a Civilian Climate Corps, limits on offshore drilling and ambitions to drive people and companies toward wind and solar power”, according to the New York Times.

Although the resulting bill is the “largest federal investment” the US has made in tackling climate change, it is “still well short of what Democrats had wanted”, the paper wrote.

The New York Times continued by noting that the bill also includes, at Manchin’s urging, “benefits for the fossil fuel industry and requirements for new oil drilling leases”.

While the Build Back Better bill would have put the country on track to achieve a 50% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 levels by the end of the decade, Democrats believe the Inflation Reduction Act will cut emissions by 40% over the same span, according to the New York Times.

A preliminary analysis (pdf) from the REPEAT Project found that the Inflation Reduction Act would cut emissions by 42% by 2030, as compared to the 46% reduction from Build Back Better. The analysis further states that the Inflation Reduction Act achieves 80% of the cumulative reductions under the House-passed Build Back Better Act.

The chart below shows the larger residual emissions gap (grey wedges) left by the Inflation Reduction Act (left pie) as compared with Build Back Better (right). It also shows that the biggest difference between the two is in the power sector, where Build Back Better would have made greater savings due to additional investment in the sector.

E&E News carried a piece explaining the difficulties of modelling the emissions impacts of the bill. It explained that while models assume people will make “economically rational decisions”, they don’t always do so. It added:

“Emissions models can understate just how difficult it will be to rapidly reduce emissions this decade. Modellers themselves are generally open about that fact. But that doesn’t stop lawmakers, advocates and the media from bandying about their findings as if emissions modelling is an exact science.”

Significantly, the New York Times reports that the new legislation is also a response to the Supreme Court’s ruling earlier in the year that restricted the EPA’s ability to cut emissions.

That decision, the newspaper notes, was based on the justification that Congress had never been granted the authority to shift the US away from fossil fuels. However, in “language written specifically to address the Supreme Court’s justification”, the new bill redefines CO2 as an “air pollutant”, meaning it can be addressed using the Clean Air Act:

“That language, according to legal experts as well as the Democrats who worked it into the legislation, explicitly gives the EPA the authority to regulate greenhouse gases and to use its power to push the adoption of wind, solar and other renewable energy sources.”

How has the media responded?

Initial agreement on the bill

The early reaction to the mooted climate, health and tax reform package in the US media could be described as cautiously optimistic.

On 28 July, the day after the agreement between Senate Democrats was announced, a Washington Post editorial said the proposed spending provisions were “not perfect”, but “compared with what Democrats previously believed they’d achieve – nothing – they are welcome”.

Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson said the deal was “better late than never” and represented “the nation’s biggest investment ever in the future of our overheating planet”. He urged Congress to “pass it quickly”, before Senator Joe Manchin “changes his mind yet again”.

The same day, in the New York Times “This Morning” newsletter, senior writer David Leonhardt wrote that “until yesterday, the Democratic Party seemed as if it were on the verge of squandering a major opportunity to combat climate change”. He said the deal was “especially significant because congressional Republicans have almost uniformly opposed policies to slow climate change (a contrast with conservatives in many other countries)”.

In the Wall Street Journal, Prof Jason Furman, professor of practice at Harvard wrote that the bill was “what the country needs now”. And Time senior correspondent Justin Worland wrote that the deal “may have saved the climate fight”.

Less keen was Washington Post columnist Henry Olsen, who wrote that “Republicans are right to oppose the new tax hike and climate spending deal” and that it “deserves to fail”, adding:

“The deal appears to be yet another liberal bait-and-switch. It pledges to raise more revenue than it spends for climate and energy programs, but the scant details on the package do not inspire confidence.”

A Wall Street Journal editorial said the bill should more accurately be called the “Business Investment Reduction and Distortion Act”. And the paper’s “Business World” opinion columnist Holman W Jenkins Jr wrote:

“The biggest wonder is the sheer size of the taxpayer sum we are getting ready to spend on climate change when nobody can honestly pretend it will have an impact on climate change”.

Reaction continued in the following days. A Los Angeles Times editorial said although the agreement package was a “diminished version” of the original Build Back Better bill, it “would still be the US government’s single biggest action on climate change in history”. However, it added:

“[L]awmakers and Biden delude themselves if they think it is ambitious enough to confront the grave and growing crisis we face from an overheating planet…It’s disappointing, though not surprising, that the agreement that ultimately satisfied Manchin’s ever-shifting goal posts includes actions that will enable more burning of fossil fuels that are causing the climate crisis.”

In the New York Times, opinion writer David Wallace-Wells said the surprise deal was “quite a reversal”, adding:

“As recently as a week ago, post-mortems were being written about not just the failure of climate legislation under Biden but also the failure of the president’s entire once-ambitious domestic-policy agenda.”

Writing in the New York Times on 1 August, columnist and Nobel prize-winning economist Prof Paul Krugman said the Act “won’t deliver everything climate activists want”, but “if it happens, it will be a major step toward saving the planet”. While hoping that “there aren’t any last-minute snags”, Krugman said the bill “could well have a catalytic effect on the energy transition” and “could also transform the political economy of climate policy”.

One thing I haven’t seen mentioned in discussions of the Inflation Reduction Act: In general, reducing greenhouse gases also reduces other air pollution, which has huge adverse health effects, mainly falling on the less well off. So an additional, strongly progressive benefit

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) August 2, 2022

On the same day, Washington Post staff writer Chris Mooney noted that “the bill won’t lead to a much cooler planet, at least not immediately or on its own”. Yet, he added, “in ways Americans may not yet appreciate, the legislation could have much more direct, soon-felt effects – on what people pay to drive and power their homes, as well as the quality of the air they breathe”.

As rumours circulated on whether Democrat Senator Kyrsten Sinema would support the bill, Krugman wrote in his New York Times column on 4 August that “Republicans are, of course, attacking the legislation”. He added:

“Misinformation aside, however, the right-wing attack on Democrats’ new climate policy is, as I said, extraordinarily weak – and that’s a wonderful thing to see.”

Meanwhile, Rolling Stone reporter Jeff Goodell wrote that, “for most people who care about the future of human civilization, last week was a very good week”, adding:

“West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin quit dicking around and announced that he would support a $369bn climate/energy deal…was the best news anyone who cares about the fate of the planet had heard in a very long time.”

Though, he noted, Machin supported the deal “only after ensuring his home state would remain a fossil fuel fiefdom”.

In a guest essay for the New York Times, Microsoft founder Bill Gates repeated the popular refrain that the bill “may be the single most important piece of climate legislation in American history”. He added that “it represents our best chance to build an energy future that is cleaner, cheaper and more secure”.

Bill passes the Senate

The formal passing of the Inflation Reduction Act through the Senate – on a 50:50 split along partisan lines, with vice-president Kamala Harris providing the casting vote – triggered another wave of reaction. On 7 August, Washington Post columnist EJ Dionne Jr wrote:

“If Congress had done nothing, the US would have squandered any claim of global leadership on one of the central challenges of our time. It also would have been a signal that our political system is so dysfunctional that it could not even enact comparatively painless, positive incentives for moving toward cleaner energy.”

In the Boston Globe, veteran climate scientist James Hansen reflected on his decades of attempts to get successive presidents to tax greenhouse gas emissions, noting that Biden “has an opportunity to take the fundamental step on climate change that eluded all past leaders, and he can start by taxing carbon emissions”.

A Washington Post editorial said the new bill was “obviously not Build Back Better”, but that “there is still a lot to like”. In another New York Times column, Krugman wrote that the act “isn’t, by itself, enough to avert climate disaster”, but “it is a huge step in the right direction and sets the stage for more action in the years ahead”. He added:

“It will catalyse progress in green technology; its economic benefits will make passing additional legislation easier; it gives the US the credibility it needs to lead a global effort to limit greenhouse gas emissions.”

In UK media, an editorial in the Financial Times noted that “the fact that almost every observer, including many Democrats, had written off any chance of a breakthrough makes it all the sweeter”. It added:

“Washington is finally taking a lead on global warming. On this basis, Biden has earned a place in the history books. The fact that Congress was still unable to embrace a carbon tax – a step that most economists insist will nonetheless be essential – should not cloud the bill’s impact.”

However, there were still detractors. Financial columnist Matthew Lynn wrote in the Daily Telegraph that the bill will “crash the world economy”. While tackling climate change is a “worthwhile cause”, said Lynn, the problem with the package is that “it isn’t going to do anything to reduce inflation – in fact it will make it much worse”.

And a Wall Street Journal editorial, quoting climate-sceptic commentator Bjorn Lomborg, said that the “climate provisions in this ballyhooed legislation will have no notable impact on the climate”. It added that “no matter what the US does to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, it will be dwarfed by what the rest of the world does”.

The passing of the act through the Senate also saw a backlash from some environmental and community groups because of its concessions to the fossil fuel industry. For example, Jean Su, energy justice programme director at the Center for Biological Diversity, told the Guardian:

“This was a backdoor take-it-or-leave-it deal between a coal baron and Democratic leaders in which any opposition from lawmakers or frontline communities was quashed. It was an inherently unjust process, a deal which sacrifices so many communities and doesn’t get us anywhere near where we need to go, yet is being presented as a saviour legislation.”

In the Guardian, Kate Aronoff – staff writer at the New Republic – described the act as “a devil’s bargain between the Democrats, the fossil fuel industry, and recalcitrant Senator Joe Manchin”. Yet, she added, “it’s better than nothing”.

BusinessGreen pulled together other reactions from politicians, experts, industry leaders and environmental groups.

Bill passes the house and is signed into Law by Biden

With the bill passing the house on 12 August, handing the Inflation Reduction Act to President Biden to sign the following week, a Guardian editorial said the “first major US climate law comes not a moment too soon”. It added:

“It is the country’s best and last opportunity to meet its goal of halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and, with it, a world where net-zero by mid-century is possible. After Donald Trump, [President] Biden can reclaim the mantle of global climate leadership for the US. But the act reveals the limits of his power.”

A news analysis piece in the New York Times noted that “passage of Friday’s bill may say less about [President] Biden’s ability to restore American bipartisanship than it does about the deep ideological breaches in his own party, which forced him to accept a much scaled-back version of his original legislative goals”.

The Atlantic’s staff writer Robinson Meyer wrote that “the bill passed only because there were 50 Democrats in the Senate, with a Democratic vice president to cast the tie-breaking vote”. He explained:

“Had any of those Democrats lost their elections – had Joe Manchin, for instance, decided against running for reelection in 2018 in his heavily Republican home state, or had Democrats not eked out two Senate wins in Georgia last year – then the bill would not have made it across the finish line.”

In the New Yorker, staff writer Elizabeth Kolbert looked at how tackling climate change has become a “partisan issue” in the US. She wrote:

“As a problem, climate change is as bipartisan as it gets: it will have equally devastating effects in red states as in blue. Last week, even as Kentucky’s two Republican senators – Rand Paul and the minority leader, Mitch McConnell – were voting against the IRA, rescuers in their state were searching for the victims of catastrophic floods caused by climate-change-supercharged rain. Meanwhile, most of Texas, whose two [Republican] senators – Ted Cruz and John Cornyn – also voted against the bill, was suffering under ‘extreme’ or ‘exceptional’ drought.”

With the news that Biden had signed the bill into law on 16 August, the Washington Post spoke to former Democrat vice president and veteran climate campaigner Al Gore. He told the outlet:

“I thought it would come much sooner than it has. I never expected to devote my life to this. And I never expected the struggle to pass this kind of legislation. It took so long.”

He noted that “the quality of our democracy has been redeemed by the passage of this legislation, but we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that our democracy has not been seriously degraded”. However, he added, “the ability of the fossil fuel industry and their lobbyists to stop climate action has been overcome, at least in this instance. And I think this will unleash so much momentum that we will never go back”.

The Inflation Reduction Act has the potential to be a historic turning point. It represents the single largest investment in climate solutions & environmental justice in US history. Decades of tireless work by climate advocates across the country led to this moment. 1/3

— Al Gore (@algore) July 28, 2022

As ever, not everyone had such glowing reflections on the new bill. Writing in the New York Times, Prof Charles Harvey, a professor of environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Dr Kurt House, chief executive officer of battery metal company, KoBold Metals, warned that the bill’s carbon capture and storage (CCS) subsidies are a “waste of money”.

They noted that “of the 12 commercial CCS projects in operation in 2021, more than 90% were engaged in enhanced oil recovery”, and argued that backing CCS allows “for the continued production of oil and natural gas at a time when the world should be ending its dependence on fossil fuels”.

And the Conversation published an article by Prof Wil Burns – professor of research in environmental policy at the American University School of International Service – in which he discussed the “major technical and political hurdles” to CCS technology, noting that “up to a fifth of emissions cuts from the Inflation Reduction Act are expected to come from carbon capture technologies”.

Finally, in the Washington Post, columnist Megan McArdle wrote that subsidies for electric vehicles – like those contained in the bill – are the “wrong way to fight climate change”. Instead, she said, “our legislative energies would be much better spent on fixing the myriad problems with our nation’s charging infrastructure”.

-

Media reaction: What Joe Biden’s landmark climate bill means for climate change