Ongoing failure to agree AR7 timeline is ‘unprecedented’ in IPCC history

Multiple Authors

11.07.25Multiple Authors

07.11.2025 | 10:39amGovernments have, once again, failed to agree on a timeline for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) seventh assessment cycle (AR7), two years into the process.

Last week, more than 300 scientists and government officials from around the world met in Lima, Peru for the 63rd session of the IPCC (IPCC-63).

According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB), reporting exclusively from inside the four-day meeting, the closed-door talks were characterised by “fraught deliberations” where “once-routine” issues became “deeply controversial and time-consuming”.

Countries reached a compromise on the content of a methodology report on carbon dioxide removal technologies – a sticking point at the last IPCC meeting.

However, the meeting marked the fourth time in a row that delegates could not reach consensus on the timings of the IPCC’s influential three-part assessment report, after deadlocked talks in Hangzhou, China earlier this year and Sofia, Bulgaria and Istanbul, Turkey in 2024.

Observers told Carbon Brief of an atmosphere of “deepening mistrust” at the meeting, as emerging economies clashed with a coalition of small-island states and developed nations amid repeated accusations of “micromanagement”.

IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea reportedly lamented in his closing remarks that “as a category five hurricane [Hurricane Melissa] swept through the Carribean, IPCC-63 was deliberating on pronouns and footnotes”.

One former IPCC author tells Carbon Brief that certain countries’ opposition to agreeing a “deadline for AR7” was a “clear tactic for playing down the importance of IPCC climate science in decision-making on climate change”.

Historic splits

Each assessment cycle, the IPCC publishes three “working group” reports that focus on climate science (WG1), impacts and adaptation (WG2) and mitigation (WG3). It also publishes a small number of special reports and methodology reports.

The IPCC’s current assessment cycle has been underway since July 2023, with the authors for its three headline reports confirmed earlier this year.

It is atypical for the IPCC to have not yet agreed when these reports would be published so far into an assessment cycle. The workplans for AR5 and AR6 were “agreed with little difficulty”, the ENB notes in its summary of the event, adding:

“The debate about the timeline is unprecedented in the history of the IPCC.”

There are, broadly speaking, two camps in the debate around timelines for AR7.

The first wants a timeline that would align the publication of the IPCC’s three headline reports, plus special and methodology reports, with the second “global stocktake” (GST).

The GST is an appraisal of global progress on tackling climate change, which takes place every five years under the Paris Agreement. The second GST is scheduled to conclude at COP33 at the end of 2028, so that its findings can inform the fourth round of national climate pledges due a few years later.

Other countries, however, have advocated for a longer timeline. Among their concerns are the potential burden reviewing reports back-to-back could place on more resource-strapped countries, as well as whether the current schedule offers enough time for gaps in scientific literature to be filled.

As proceedings kicked off in Peru, the IPCC proposed a timeline for AR7 which would see all three of its headline reports published in 2028, with approval sessions earmarked for May, June and July of that year for the three working group reports.

WGI co-chair Dr Robert Vautard noted that the ongoing uncertainty on timelines was stressful for both the authors of reports, as well as for scientists wishing to submit research for the cycle, according to the ENB.

The delegation from Antigua and Barbuda, meanwhile, noted that agreement on the timeline is typically procedural and “not negotiated by governments”. It also said the proposed cycle length of around six-and-a-half years was consistent with the IPCC’s last two assessment cycles.

‘Compromise’ timeline

Throughout the four-day meeting, positions on both sides on the debate around AR7 remained “entrenched”, the ENB notes.

A “majority” of countries were in favour of a workplan which would align AR7 with the GST, the ENB says. However, this group was opposed by a “smaller, but growing” number of countries in favour of a less compressed timeline.

Early on in proceedings, for example, Kenya described a slower timeline as a “great equaliser” and said a more compressed timeline did not favour authors, nor the coordinating agencies, from developing countries, ENB says.

Meanwhile, India argued that the GST was “extraneous” to the IPCC and said there were no formal IPCC rules about aligning with the stocktaking exercise, according to ENB. Algeria, China, Libya, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa also reportedly voiced their opposition to the IPCC’s proposals.

Inclusivity concerns were also cited by countries in favour of the IPCC’s timeline. For example, the small-island state of Vanuatu reportedly said that delaying the reports would deprive countries of important scientific information ahead of key international meetings.

Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, the Bahamas, France, the Gambia, Korea and Nepal were among the countries to speak up in favour of the IPCC’s proposed timeline, according to ENB.

Simon Steill, executive director of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), urged countries to agree on a timeline which aligned AR7 with the GST. In his opening address to the Lima meeting, he said:

“Taken together, the reports will be indispensable and I will continue to urge all countries to agree on timelines that ensure all three assessments inform the second global stocktake.

“Because the stocktake is not just a technical exercise. It is a crucial moment for the world to recognise the state of play, reaffirm its commitment to Paris and respond with action and support at the pace and scale that science demands.”

The ENB reports that a contact group was set up on Monday to work through the issue, co-chaired by Brazil and Denmark.

On Tuesday, a revised timeline for AR7 was presented by WG1 co-chair Dr Xiaoye Zhang and WG2 co-chair Dr Bart Van den Hurk, which took into account deliberations from the contact group, the ENB says. It set out a number of changes to the initial timeline, concentrated at the end of the cycle so as to address government concerns while limiting impacts on report authors.

This included spacing out approval sessions – where the final reports are signed off line by line – so that WG2 would be held in July 2028 (instead of June) and WG3 in September (instead of July). It also set out an extension of expert and government review periods for report drafts.

Discussion of the revised schedule was deferred until Wednesday at the request of Ghana, Kenya, India, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

As talks resumed, a number of emerging-economy countries spoke out against the updated timeline, including Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and Zimbabwe, ENB notes.

Russia said that aligning the work of the IPCC with the UNFCCC would send a “negative signal”, ENB says, whereas China suggested that the timeline would put “pressure” on developing countries. South Africa similarly argued that the timeline would “harm” the inclusivity and geographic representativeness of the reports, according to ENB.

Among the countries in favour of the revised timeline were small-island developing states Haiti, Jamaica, Sao Tome and Principe and Vanuatu, as well developed economies Australia, Finland, Italy, Ireland, New Zealand and the UK, ENB says.

Grenada is quoted by ENB as describing the new timeline constituted a “compromise of a compromise”. The country also emphasised that it was supported by a majority of countries across regions and development levels, ENB says.

At the request of certain members of the contact group, WG1’s Vautard presented a visualisation of the new timeline for all three reports and the special report on cities on Wednesday evening. The graphic – seen by Carbon Brief – plots the timeline for “first-order” draft review (by experts), “second-order” draft review (by governments and experts), final government review and panel approval for each report.

Vautard noted that first-order draft reviews of the WG1 and WG2 reports overlapped “intentionally”, to allow experts to see both drafts at once.

(The request for a visualisation prompted accusations – not for the first time at the meeting – that certain countries were drawing the IPCC process into “micromanagement”, the ENB notes.)

The visualisation was followed by a new wave of objections from countries, who argued against a timeline where review periods for different reports overlapped with each other and UNFCCC meetings, according to ENB.

Among them were Russia and China, who argued that AR7 should be extended to 2029, ENB says. (Russia reportedly said it would “consider a plan” to deliver the overarching synthesis report by December 2029 – if its concerns were addressed.)

On the other hand, Antigua and Barbuda argued that avoiding any overlaps would not be feasible and expressed concerns that certain countries’ interventions seemed to be aimed “more at delay than progress”, the ENB notes.

Skea said he “struggled to see” why consecutive and overlapping reviews were a problem, according to the ENB. He noted that the IPCC rulebook states that panel and working group sessions should be scheduled to coordinate with, “to the extent possible, with other related international meetings”.

Lindsey Fielder-Cook, interim deputy director and the representative for climate change at the Quaker UN Office, was an observer to the talks. She tells Carbon Brief that “blocking” governments had “serious and genuine concerns” around the lack of equity inclusion in climate modelling and a failure of co-chairs to “sufficiently engage” with their proposals.

However, she says these countries also cited “structural” concerns around timing and capacity that “could be overcome” and speculated that these were “used to cover [for] what the countries do not say publicly”. She adds:

“For example, concerns include capacity and vacation times during [report] review times – which were not a concern raised by small-island developing states and many least-developed countries with even less capacity, [as well as concerns about] developing country scientific input, which the IPCC has made genuine efforts to improve.”

On Thursday evening, the facilitators of the contact group reported that no consensus had been reached, the ENB notes. Consequently, the IPCC agreed to – once again – defer decisions on the rest of the workplan to a future session.

Countries agreed that working groups should press on with activities and author meetings detailed in the 2026 budget.

(This outcome – where the IPCC plans in annual increments – had been described earlier in the week by Skea as the “worst option”. Nepal, meanwhile, said this result would “harm the IPCC’s legitimacy”.)

Routine issues ‘have become controversial’

This is now the fourth meeting in a row – following Istanbul, Sofia and Hangzhou – where the timeline for producing, reviewing and publishing the IPCC’s reports in AR7 has not been agreed.

In its analysis of the “fraught negotiations” in Lima, the ENB notes that “deep divisions” on the timeline and other procedural issues have “plagued the IPCC during the first two years of its seventh assessment cycle”. It added:

“Issues that were once routine have become deeply controversial and time-consuming.”

The failure to approve the timeline for AR7 was not the only issue on which countries were unable to agree. Approval of the official summaries of the two preceding IPCC meetings was also deferred, after certain countries said they could not sign off on the drafts.

After the previous IPCC meeting in Hangzhou, Skea told Carbon Brief that negotiations over just the outlines of the three AR7 working group reports “had some of the quality of an approval session”, where a finished report is scrutinised line by line.

In Lima, Skea “remarked that these disagreements [over the timeline] are unprecedented so early in an assessment cycle”, the ENB reports.

Throughout the meeting, the ENB records multiple instances of countries voicing their concerns about the implications for the work of the IPCC.

In its analysis of the meeting, the ENB says these concerns reflect “growing tensions within the panel, as “delegates expressed increasing frustration with what they see as inflexible positions”.

The ENB also notes:

“References made in this session to disrespectful interactions among delegates are atypical in the IPCC context and raise concerns that trust the basis for compromise and flexibility may be dwindling in some parts of the IPCC.”

(The IPCC has not responded to Carbon Brief’s multiple interview requests.)

In her observations, Fielder-Cook tells Carbon Brief that the meeting was “actually more relaxed” than recent IPCC sessions. This was “in part due to the gentle and generous hosting of Peru and in part to a sense of resignation on the timeline”.

Nonetheless, she says, the mood in the room was of “concern for the IPCC and its reputation, for its ability to protect science from intensifying political influence”, as well as “concern over the increasing political efforts to influence the scientific output”. She adds:

“While the work will continue, IPCC authors working voluntarily have no clear timeline on their voluntary commitment.”

Prof Lisa Schipper, a professor of development geography at the University of Bonn and IPCC AR6 author, tells Carbon Brief:

“Some countries refusing to set a deadline for the AR7 is a clear tactic for playing down the importance of IPCC climate science in decision-making on climate change. And this will be a problem if the report is done and cannot be approved and used by governments.”

Nonetheless, she adds, “there is plenty of good science being produced and governments are not in any way restricted from using this science in their decision-making”.

Ultimately, though, “we do need a decision on the AR7 timeline”, she says:

“No other single report provides the same evaluation and assessment of this collected knowledge or is able to give an authoritative overview of what we know, what we don’t know, and which future is more likely under different conditions.”

Consensus on CDR

Earlier this year in Hangzhou, governments failed to reach consensus on the outline for a methodology report on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies, which is slated for publication in 2027.

This was largely due to disagreements around chapter seven in the proposed outline, a section that would focus on carbon removals from oceans, lakes and rivers.

On the first day in Lima, Takeshi Enoki – a co-chair of the IPCC task force on national greenhouse gas inventories (TFI), which is responsible for producing the report – introduced the outline and workplan for the methodology report.

Enoki explained that discussions about the report would focus on the table of contents and “particularly the proposed volume seven on the direct removal of CO2 from waterbodies”, according to ENB.

Fielder-Cook – the observer from the Quaker UN Office – tells Carbon Brief there was “significant concern” across a “range of developed and developing countries” over language in the initial methodology report outline that “could allow harmful marine geoengineering”.

Antigua and Barbuda, France and Germany were among the countries who opposed the inclusion of a seventh chapter. They cited concerns related to the “effectiveness, scalability, legality and environmental impacts” of marine CDR, the ENB notes.

Some of these countries suggested that the IPCC adopt the outline for “volumes one to six”, “with the possibility of adding to these volumes later”, the ENB says.

However, Saudi Arabia said that all “expert-recognised CDR and CCUS technologies, including marine-based technologies, must be considered”. It called for an outline that “encompasses the full spectrum of these technologies”.

ENB notes that the “point of contention” was whether the IPCC should develop methodologies for measuring and assessing the impacts of all CDR technologies. Some countries argued that the report should be limited to technologies that are “environmentally safe”, while others argued that it is “not the responsibility of a TFI methodology report to make that judgment”.

Skea set up a contact group on the first day of the meeting, facilitated by China and Turkey, to work on the outline of the report.

The following days saw “significant discussion” within the contact group, before delegates reconvened in plenary on Thursday to continue discussing the report, according to the ENB.

Delegates were eventually able to reach a compromise on the outline by agreeing to remove the chapter on direct removal of CO2 from waterbodies from the plan, the ENB reports.

Meanwhile, delegates agreed to hold an expert meeting on alkalinity enhancement – the addition of alkaline substances to seawater, which allows the ocean to take in more carbon from the atmosphere – and direct ocean capture. This meeting will be co-organised by the TFI and the three IPCC working groups.

Funding ‘shortfall’

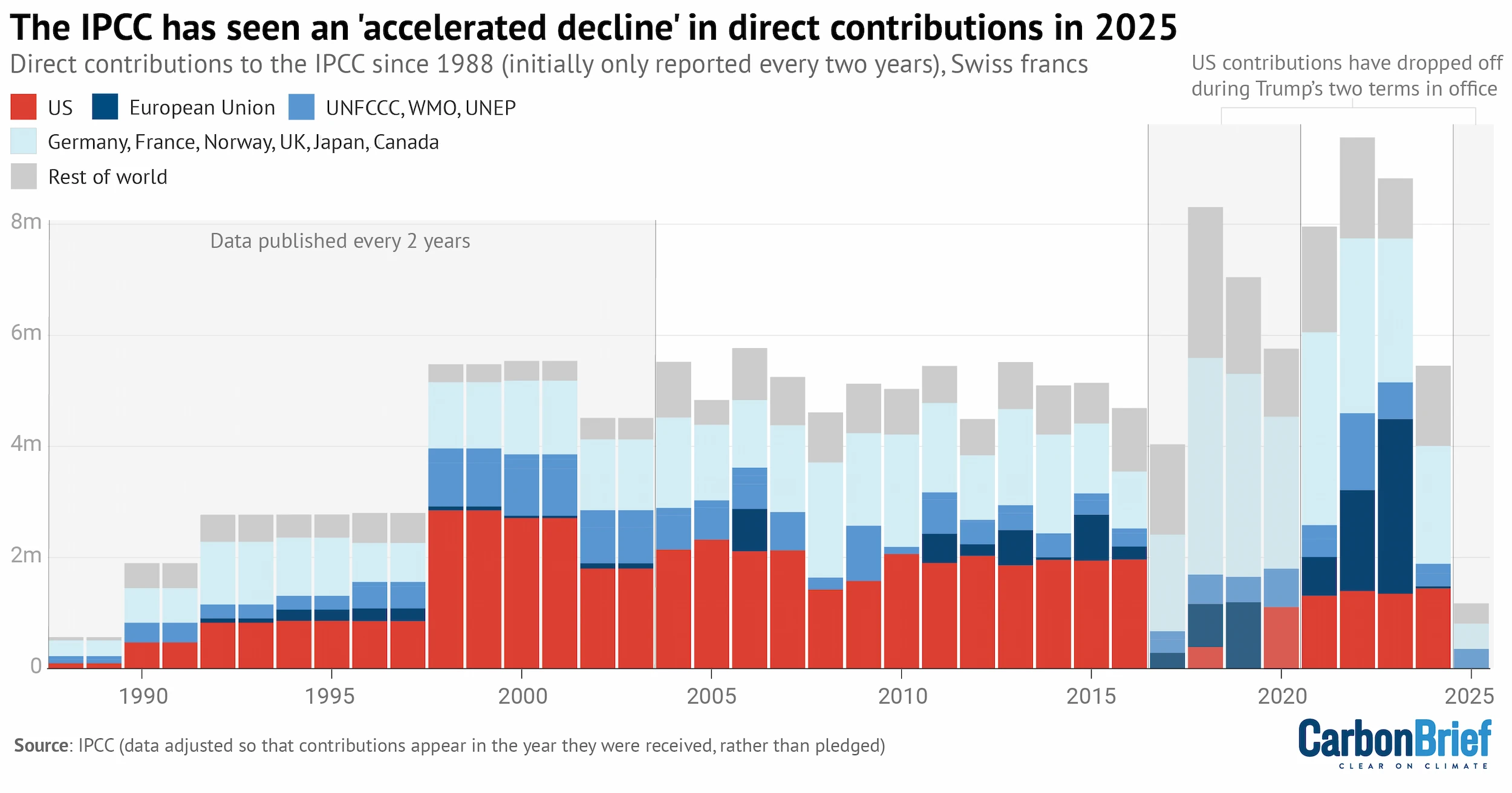

At the Lima meeting, countries approved the IPCC’s budgets for 2025 and 2026, but also noted “with concern the significantly reduced cash balance” of the IPCC trust fund and the “accelerating decline” in the level of annual voluntary contributions from countries and other organisations, says the ENB.

The IPCC is funded by its parent organisations, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and UN Environment Programme (UNEP), along with voluntary contributions from member governments and the UNFCCC.

These contributions feed into the IPCC “trust fund”, which is used to pay for the work of the IPCC. In addition, member countries provide “in-kind” support, such as offering facilities for meetings and hosting the “technical support units” for each working group.

By the end of June, contributions in 2025 amounted to 1.2m Swiss francs (£1.1m) – significantly down compared to the annual totals of previous years. Compared to spending of 2.9m Swiss francs (£2.8m), this leaves a shortfall of around 1.7m Swiss francs (£1.6m) for 2025.

At the start of this year, the balance of the trust fund stood at 17.8m Swiss francs (£16.9m).

The chart below shows the direct contributions from countries and organisations throughout the IPCC’s history and up to the end of June this year.

The largest direct contributions to the IPCC trust fund so far this year have come from Norway (244,000 Swiss francs, or £230,000), the UNFCCC (230,000 Swiss francs, or £220,000), Canada (210,000 Swiss francs, or £200,000) and the WMO (125,000 Swiss francs, or £118,000).

Other countries to contribute this year include Australia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Peru, South Korea, Sweden, Trinidad and Tobago, and 213 Swiss francs (£200) from Cambodia.

The US – which has provided 30% of the IPCC’s direct contributions throughout its history – has not made a contribution so far this year.

In its final decision, the panel invited “member countries to make their annual voluntary contributions to the IPCC trust fund and, if possible, to increase [them]”, says the ENB.

Member countries also discussed a proposal from the WMO for the IPCC to pay 300,000 Swiss francs (£280,000) for administrative support that was previously provided as an in-kind contribution.

Given the “deteriorating financial situation” of the IPCC, the ENB reports that a decision on this proposal was deferred – not to the next meeting, but the one after that.

Progress reports and next steps

The Lima meeting was also an opportunity for each IPCC working group to update the rest of the delegates on progress since the last meeting.

All working groups discussed the process of selecting authors for the IPCC’s upcoming seventh assessment, highlighting their efforts to be “inclusive”.

For example, the WG3 co-chair said 52% of the selected WG3 authors are from developing countries, 40% are female and 59% are new to the IPCC.

A WG2 co-chair also reported that six chapter scientists had been selected from more than 1,320 applications for the special report on cities slated for publication in March 2027.

In addition, the WG1 co-chairs outlined their preparations for the first joint-lead author meeting for their assessment report, which will be held in December 2025.

They also laid out plans for a cross-working group “expert meeting” on “Earth system high impact events, tipping points and their consequences”, co-sponsored by the World Climate Research Programme (WCPR).

The meeting also granted “observer status” to 20 new organisations, allowing them to attend IPCC sessions and nominate experts as authors or workshop leads.

The IPCC confirmed that its next meeting will be held in Bangkok, Thailand over 24-27 March 2026.

Skea announced that workshops on “diverse knowledge systems and methods of assessment” will be held in February 2026 at the University of Reading in the UK.

Skea also proposed an expert meeting to “support the transition from conceptual design to technical implementation” of the AR7 WG1 and WG2 interactive atlases.

The atlases are interactive online tools that allow users to explore much of the data underpinning the working group reports.

The meeting was approved, subject to agreement on the budget. It is slated to take place between April and June 2026.