Q&A: European Commission’s proposal to cut EU emissions 90% by 2040

Multiple Authors

07.03.25Multiple Authors

03.07.2025 | 4:45pmThe European Commission has set out a proposal to cut EU emissions 90% by 2040, with up to 3% coming via carbon credits purchased from other countries.

In a proposed amendment to EU climate legislation, the commission has laid out what it calls a “new way to get to 2040”, including “flexibilities” to ease the burden on member states.

Besides the limited use of carbon credits, the proposal also gives a potentially larger role to carbon dioxide (CO2) removal technologies and leaves the door open for weaker sectoral goals.

It has drawn criticism from climate NGOs and left-leaning European politicians, who argue that it “waters down” the EU’s climate ambitions and presents “considerable risks”.

Yet, the proposal is seen by many as an acceptable compromise option, following strong pushback from many member states to the 90% target, originally proposed last year.

With all nations expected to come forward with new international climate targets for 2035 by September and ahead of the COP30 climate summit, the 2040 goal will also be crucial in determining where the EU’s pledge lands.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief outlines what the amendment proposed by the commission includes, why it has proved controversial and what is expected to happen next.

- What has the European Commission proposed?

- Why is the commission making this proposal now?

- What does it say about international carbon credits and ‘flexibilities’?

- Who has supported and opposed the proposed climate target?

- How does the goal fit with the EU’s industrial growth plans?

- What comes next?

What has the European Commission proposed?

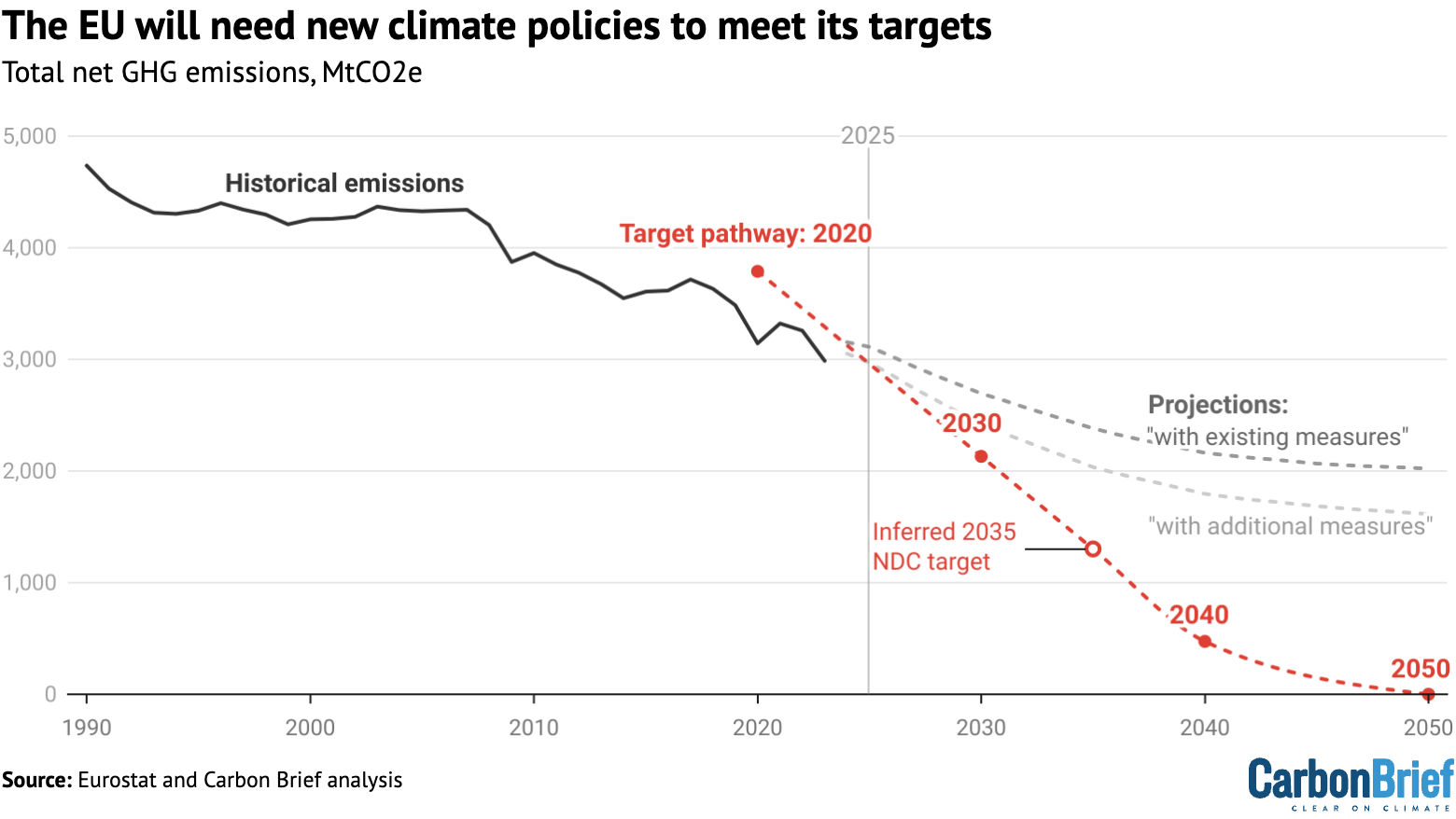

The European Commission has proposed an amendment to the EU Climate Law, which would set a target for a 90% reduction in net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2040, compared to 1990 levels.

It will “give certainty to investors, innovation, strengthen industrial leadership of our businesses and increase Europe’s energy security”, the commission says.

In a statement, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, added:

“As European citizens increasingly feel the impact of climate change, they expect Europe to act. Industry and investors look to us to set a predictable direction of travel. Today we show that we stand firmly by our commitment to decarbonise [the] European economy by 2050. The goal is clear, the journey is pragmatic and realistic.”

The proposal includes new “flexibilities”, such as a limited role for “high-quality international credits” from 2036, the use of domestic permanent emissions removals within the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and additional flexibilities across certain hard-to-decarbonise sectors.

These additional flexibilities are designed to allow countries to meet targets in a cost-effective and “socially fair” way, the commission adds. It says they will provide the possibility that a member state could compensate for a struggling land-use sector with overachievement in other areas, such as emissions from waste or transport.

The target will “send a signal to the global community” that the EU will “stay the course on climate change, deliver the Paris Agreement and continue engaging with partner countries to reduce global emissions”, says the commission.

It has been announced ahead of the UN COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil in November.

The European Commission says it will now work with the council presidency – representing EU member state governments – to finalise the EU’s climate pledges for 2035, so that the EU can submit its “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

The EU was among the 95% of countries that missed the UN deadline to submit their NDCs by February of this year.

A recent update from the European parliament noted that the EU “needs to update its NDC…by September”, in order to meet an extended deadline from the UN.

In 2023, independent advisory body the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change recommended that the EU should aim for net emissions reductions of 90-95% by 2040, compared to 1990 levels.

As such, the advisory board said that the bloc would need to limit its cumulative emissions from 2030-50 to 11-14bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e), in order to be in line with bringing global warming down to 1.5C by the end of the century.

The 90% emissions reduction figure set out by the EU is on the lower end of guidance.

Why is the commission making this proposal now?

The European Commission’s new proposal builds on previous targets and roadmaps, representing a significant step towards enshrining the 2040 target in law.

In July 2021, the European Climate Law officially entered into force, setting a target of a net GHG reduction of at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels, as shown in the chart below.

Rules were introduced governing sectors, such as clean energy, energy efficiency and transport, among others, to help meet this target.

If all were successful in their implementation, they would reduce emissions by roughly 57% by 2030, according to a European parliament assessment in 2022.

Subsequently, the commission has been working on developing a target for 2040, as an interim benchmark between the 2030 target and the EU goal – announced in 2018 – to be “climate neutral” by 2050. At this point, the bloc would reach net-zero emissions overall and would stop adding to global warming.

In 2024, the commission published an impact assessment, detailing the underlying qualitative analysis it had undertaken around emissions reduction targets for 2040.

This, together with the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change’s report (detailed above) and advice from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, formed the basis for the 90% target, the commission says.

The headline 90% target for 2040 was announced as part of a roadmap outlined by the commission in February 2024.

The roadmap kicked off a lengthy process in which EU politicians and institutions worked to cement the details of this target, ahead of this week’s proposal on turning it into law.

This process included “substantial engagement” with member states, the European parliament, stakeholders, civil society and citizens, the commission says.

In particular, certain European countries have been placing pressure on the commission to change or adapt the 2040 target, slowing the progress of this week’s proposal, which had been due out in February.

For example, Italy called for the goal to be weakened and France asked for “flexibility” to be introduced (See: Who has supported and opposed the proposed climate target?).

The commission hopes that publishing the proposed target now will allow it to be factored into the EU’s upcoming NDC, in which it will establish an emissions reduction target for 2035.

What does it say about international carbon credits and ‘flexibilities’?

The European Commission’s proposal sets out a “pragmatic” pathway towards the 2040 target, including specific measures to give EU member states “flexibility”.

Of these, the one that has received the most attention is to allow limited use of international carbon credits, under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, starting in 2036.

In effect, this flexibility means that emissions within the EU would only need to fall to 87% below 1990 levels by 2040, with the remaining 3% taking place overseas.

This would mean member states could buy credits generated by emissions-cutting projects in other countries and count those cuts towards their own targets.

Other nations, including Japan and Switzerland, have already welcomed the use of international credits to meet their climate goals.

In an unusual intervention that coincided with the proposal itself, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change stated that the EU should not count such credits towards the 2040 target. It said:

“Using international carbon credits to meet this target, even partially, could undermine domestic value creation by diverting resources from the necessary transformation of the EU’s economy.”

The board also mentioned other concerns that are frequently levelled at “carbon offsetting”, such as credits not resulting in real-world emissions cuts.

The commission’s proposal refers to “high-quality international credits under Article 6”, but does not specify which types of credit. This leaves the door open for lower quality options.

For example, carbon trading under Article 6.2 is subject to far less oversight than trading of Article 6.4 credits.

The proposal also states that: “The origin, quality criteria and other conditions concerning the acquisition and use of any such credits shall be regulated in union law.”

This suggests that the EU would conduct its own assessment of any credits used by member states, beyond the rules that have been negotiated at an international level.

Jonathan Crook, the lead expert on global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch, tells Carbon Brief that additional safeguards would be “essential”, given outstanding issues with Article 6 carbon credits.

A Q&A accompanying the commission proposal states that credits would be bought from “credible and transformative” projects in nations with Paris-aligned climate goals.

It mentions direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) as examples of the kinds of projects that the EU could source credits from.

This could severely limit the pool of available credits, because – as it stands – almost all carbon credits are from tree planting, forest conservation and clean-energy projects.

DACCS and BECCS projects could result in relatively permanent carbon removal. Crook says this would be one of the “many necessary safeguards” needed for credit purchases, although he points to potential issues with such projects. He adds:

“This potential durability criterion is only mentioned in the Q&A, rather than in the actual commission proposal and so currently has very limited standing unless it is introduced [into the legal text] during the co-legislation process.”

There are two additional “new flexibilities” mentioned in the commission’s proposal, to help member states meet the 2040 emissions target more easily.

One is the inclusion of permanent carbon dioxide (CO2) removal in the EU ETS, something that was already being discussed as part of an ETS revision.

This would mean that DACCS and BECCS projects in EU member states could sell credits to help high-emitting companies, such as steel plant operators, stay within their ETS limits.

Paying for such credits could become more appealing as the number of available emissions “allowances” under the overall “cap” for ETS system shrinks and the allowances become more expensive.

The commission says this would help to “compensate for residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors”, referring to those that are expensive or difficult to reduce to zero.

The need to remove CO2 from the atmosphere is widely recognised and inclusion in the ETS could help to drive investment into early-stage technologies, such as DACCS.

However, there are concerns that focusing on removals diverts investment from readily available technologies that cut emissions, such as electric-arc furnaces for steel plants.

In its recommendations, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change says there should be separate targets for emissions reductions and removals. This would ensure the removals contribute to EU targets “without deterring emission reductions”, it says.

Finally, the commission’s proposal also includes a vague mention of “enhanced flexibility across sectors, to support the achievement of targets in a cost-effective way”.

Linda Kalcher, executive director of the thinktank Strategic Perspectives, tells Carbon Brief that this is “alluding to the fact that we might see weakening of some laws”.

Michael Forte, a senior policy advisor at thinktank E3G, expands on this, noting that it could mean member states adjusting emissions targets between different parts of the EU climate architecture, depending on where they were over- or underperforming.

“I would infer that this means letting member states transfer a greater share of their mitigation efforts between these different instruments,” Forte tells Carbon Brief.

Kalcher notes that such changes cannot be regulated in this law, but instead would need to be part of the expected 2040 framework or other pieces of law:

“They are more alluding to future changes, instead of making them now. So that…gives confidence to the countries that have concerns [about the 2040 target] that something will happen.”

Who has supported and opposed the proposed climate target?

Climate campaigners and left-leaning politicians were highly critical of the “flexibilities” included in the commission’s proposal, in particular the use of international carbon credits.

The options proposed were described by civil-society groups as “creative accounting” and a “dangerous new precedent” that relies on “outsourcing Europe’s responsibility” to other countries.

The European parliament’s centre-left Socialists and Democrats coalition issued a statement warning that “the inclusion of international carbon credits as a means to meet the target carries considerable risks”.

Critics also noted that using such flexibilities contradicted the official advice offered by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change.

Yet the proposal, presented as a “new way to get to 2040”, is widely viewed as an attempt to find a political compromise against a tricky geopolitical backdrop.

It allows the EU to aim for the target set out by its scientific advisers, albeit at the lower end of the “90-95%” emissions reduction that had been proposed. This is in spite of a strong political pushback from some member states.

A statement released by Peter Liese and Christian Ehler, German members of the European parliament’s centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) group, explained:

“We think it’s very dangerous to criticise the European Commission because they intend to include flexibility in their proposal on the 2040 target. We don’t see a majority in parliament nor council for any 2040 target without flexibility.”

Some member states, including Spain and Denmark, supported the 90% target without asking for major concessions. Others, including Poland and Italy, have argued for a less stringent headline goal.

Meanwhile, others pushed for some kind of compromise during discussions of the new target.

Notably, the newly elected, right-leaning German government gave qualified support for the 90% goal in its coalition agreement, subject to conditions such as the inclusion of international carbon credits. Other influential nations have also increasingly stressed the need for “flexibility” around the target.

Meanwhile, according to Politico, France has been part of a push – alongside “climate laggards” Hungary and Poland – to separate discussions of the EU’s domestic 2040 target from its international 2035 NDC pledge.

According to the news outlet, such decoupling could result in a weaker 2035 target, compared to the 2035 target that is expected to be derived from the 90% reduction 2040 goal.

How does the goal fit with the EU’s industrial growth plans?

The commission says its 2040 proposal goes “hand in hand” with its clean industrial deal strategy, its affordable energy action plan and its “competitiveness compass” plan.

Alongside tabling its 2040 climate goal, the commission issued a new “communication” on “delivering on the clean industrial deal”. (The deal was first announced in February.)

The communication says that “decarbonisation and reindustrialisation are two sides of the same coin” and reaffirms that the aim of the deal is to “enable the EU to lead in

developing the clean-technology markets of the future”.

The commission says delivery of the deal is “already underway”. It points to the adoption of the clean industrial deal state aid framework on 25 June, an €85bn ($100bn) state-aid package for helping member states transition their economies.

Environmental law charity Client Earth said a draft version of the framework risked “entrenching support for fossil gas and fossil based low-carbon gases”.

The clean industrial deal communication also notes that the commission this week published recommendations on tax incentives for speeding up the energy transition.

On 18 June, the European parliament and council agreed on a commission proposal to simplify the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a policy for taxing carbon-intensive imports at levels equivalent to the EU ETS.

The agreement introduces a new exemption threshold of 50 tonnes for CBAM goods, meaning small and medium-sized companies that do not exceed this weight of imports per year will now be exempt from the measure.

EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra described it as a “win for both climate policy and competitiveness of our companies”, with the new measure meaning 90% of companies will now be exempt from the CBAM, but 99% of emissions will still be covered.

Previous analysis has found that, in isolation, the CBAM will have a limited impact on global emissions.

What comes next?

Before the target can be adopted, it must be agreed by member states and pass through the European parliament.

Once the parliament and national ministers have agreed on their separate positions, three-way “trialogue” negotiations between them and the commission can begin with the aim of finalising the 2040 legislative proposal.

All nations were asked to submit new 2035 climate pledges, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), to the UN by February of this year (see: What has the European Commission proposed?). The EU was among the vast majority of parties to miss the deadline.

UN climate chief Simon Stiell has now asked all parties to submit their NDCs “by September”. This is to allow time for the preparation of a report on the collective ambition of all nations’ pledges before COP30 in November.

The EU’s NDC will include an “indicative 2035 figure” derived from the bloc’s 2040 climate target, according to the commission.

The commission says it will work with the Danish presidency of the EU council and member states to finalise its NDC.

It is expected that the EU will aim to finalise both its 2035 NDC and its 2040 climate goal ahead of the next UN general assembly, which starts on 9 September in New York.