Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action?

Multiple Authors

09.25.25Multiple Authors

25.09.2025 | 4:58pmPresident Xi Jinping has personally pledged to cut China’s greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This is China’s third pledge under the Paris Agreement, but is the first to put firm constraints on the country’s emissions by setting an “absolute” target to reduce them.

These targets have been affirmed in China’s official 2035 “nationally determined contribution” (NDC), published on 3 November.

China’s leader spoke via video to a UN climate summit in New York organised by secretary general António Guterres, making comments seen as a “veiled swipe” at US president Donald Trump.

The headline target, with its undefined peak-year baseline, falls “far short” of what would have been needed to help limit warming to well-below 2C or 1.5C, according to experts.

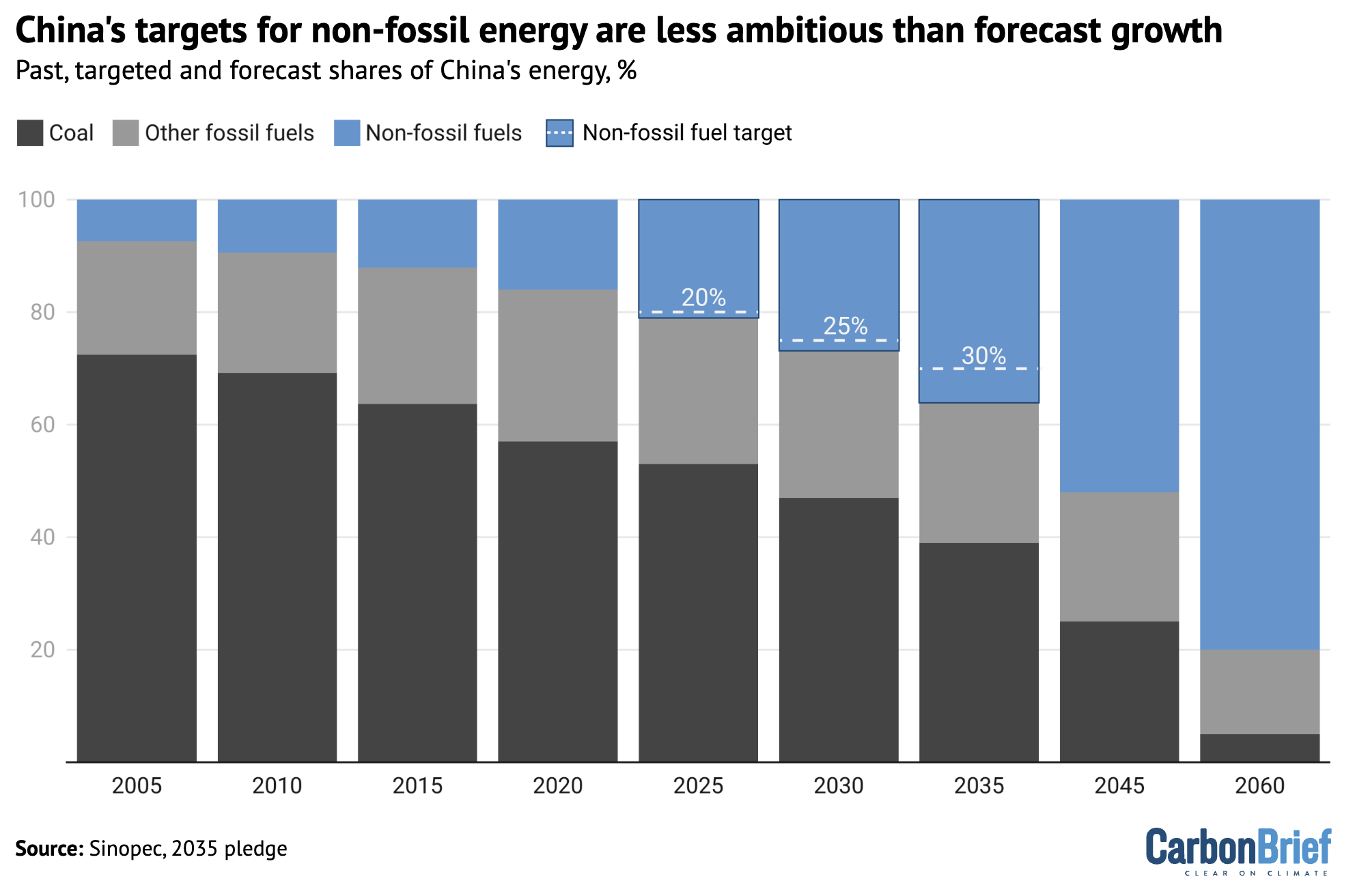

Moreover, Xi’s pledge for non-fossil fuels to make up 30% of China’s energy is far below the latest forecasts, while his goal for wind and solar capacity to reach 3,600 gigawatts (GW) implies a significant slowdown, relative to recent growth.

Overall, the targets have received a lukewarm response, described as “conservative”, “too weak” and as not reflecting the pace of clean-energy expansion on the ground.

Nevertheless, Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), tells Carbon Brief that the pledge marks a “big psychological jump for the Chinese”, shifting from targets that constrained emissions growth to a requirement to cut them.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks what China’s new targets mean for its emissions and energy use. (This article was updated on 4 November with further details from the country’s full NDC.)

- What is in China’s new climate pledge?

- What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

- What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

- What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

- How does the new NDC talk about global ‘climate cooperation’?

- What else is in China’s new pledge?

- How was Xi’s announcement received?

What is in China’s new climate pledge?

The headline targets in China’s 2035 NDC were first revealed in a speech by Chinese president Xi Jinping to the UN.

Xi’s speech is the first time his country has promised to place an absolute limit on its greenhouse gas emissions, marking a significant shift in approach.

Xi had previously pledged that China would peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions “before 2030”, without defining at what level, reaching “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

He also outlined a handful of other key targets for 2035, shown in the table below against the goals set in previous NDCs.

| Indicators | Targets for 2035 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First NDC (2016) | NDC 2.0 (2021) | NDC 3.0 (2025) | |

| Emissions target | Peak CO2 “around 2030”, “making best efforts to peak early” | Peak CO2 “before 2030” and “achieve carbon neutrality before 2060” | Cut GHGs to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035 |

| CO2 intensity reduction (compared to 2005) | 60-65% | >65% | - |

| Non-fossil share in primary energy mix | Around 20% | Around 25% | 30% |

| Forest stock volume increase (compared to 2005) | Around 4.5bn cubic metres | 6bn cubic metres | 11bn cubic metres |

| Installed capacity of wind and solar power | - | >1,200GW | >3,600GW |

In his speech, Xi also said that, by 2035, “new energy vehicles” would be the “mainstream” for new vehicle sales, China’s national carbon market would cover all “major high-emission industries” and that a “climate-adaptive society” would be “basically established”.

Xia Yingxian, director of the department of climate change at China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), told reporters that the pledges emphasise “China’s firm resolve to uphold multilateralism, lead the green and low-carbon transition…and help build a clean and beautiful world amid complex and evolving international circumstances”.

This is the first time that China’s targets will cover the entire economy and all greenhouse gases (GHGs), a move that has been long signalled by Chinese policymakers.

In 2023, the joint China-US Sunnylands statement, released during the Biden administration, had said that both countries’ 2035 NDCs “will be economy-wide, include all GHGs and reflect…[the goal of] holding the increase in global average temperature to well-below 2C”.

Subsequently, the world’s first global stocktake, issued at COP28 in Dubai, “encourage[d]” all countries to submit “ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets, covering all GHGs, sectors and categories…aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C”.

Responding to this the following year, executive vice-premier and climate lead Ding Xuexiang stated at COP29 in Baku that China’s 2035 climate pledge would be economy-wide and cover all GHGs. (His remarks did not mention alignment with 1.5C.)

This was reiterated by Xi at a climate meeting between world leaders in April 2025.

The absolute target for all greenhouse gases marks a turning point in China’s emissions strategy. Until now, China’s emissions targets have largely focused on carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP, a metric that does not directly constrain emissions as a whole.

The change aligns with China’s broader shift from “dual control of energy” towards “dual control of carbon”, a policy that replaces China’s current tradition of setting targets for energy intensity and total energy consumption, with carbon intensity and carbon emissions.

Under the policy, in the 15th five-year plan period (2026-2030), China will continue to centre carbon intensity as its main metric for emissions reduction. After 2030, an absolute cap on carbon emissions will become the predominant target.

China’s top leaders confirmed at a meeting in September 2025 that climate policy will be a priority in the plan, which is expected to be published during the “two sessions” meetings in March 2026.

The climate and energy pledges included within – particularly the quantitative targets it sets for 2030 – will be a clear indication of how China intends to peak its emissions.

What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

In his UN address, Xi pledged to cut China’s “economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions” to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This means the target includes not just CO2, but also methane, nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases, all of which make significant contributions to global warming. (See: What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?)

The reference to “economy-wide net” emissions means that the target refers to the total of China’s emissions, from all sources, minus removals, which could come from natural sources, such as afforestation, or via “carbon dioxide removal” technologies.

However, the pledge did not include a base year from which emissions will fall.

By not specifying a starting year for emission reductions, Chinese policymakers are signalling that they are not yet convinced that China’s emissions have peaked, according to experts speaking on a Carbon Brief webinar in September.

(Analysis for Carbon Brief has found that China’s emissions may have already passed a peak.)

Thinktank E3G says the lack of a base year could give local authorities a “free pass to increase emissions until 2030” and risks “locking in could-be-built coal-fired power infrastructure”.

Outlining the targets, Xi told the UN summit that they represented China’s “best efforts, based on the requirements of the Paris Agreement”. He added:

“Meeting these targets requires both painstaking efforts by China itself and a supportive and open international environment. We have the resolve and confidence to deliver on our commitments.”

The full NDC notes that the country’s climate targets are developed within the “broader context of economic and social progress”, taking into consideration domestic and geopolitical “circumstances”, as well as “balancing development with emissions reduction”.

It adds that the 2035 emissions reduction target “aligns with the 1.5C and 2C scenarios outlined” in the global stocktake and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report.

It adds: “This reflects a net-zero carbon resilient development pathway consistent with achieving the Paris Agreement’s long-term goal, representing [China’s] maximum possible effort.”

China has a reputation for under-promising and over-delivering, although notably it is currently not on track to fulfil its carbon intensity target for 2030.

Prof Wang Zhongying, director-general of the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affiliated thinktank, told Carbon Brief in an interview at COP26 that China’s policy targets represent a “bottom line”, which the policymakers are “definitely certain” about meeting. He views this as a “cultural difference”, relative to other countries.

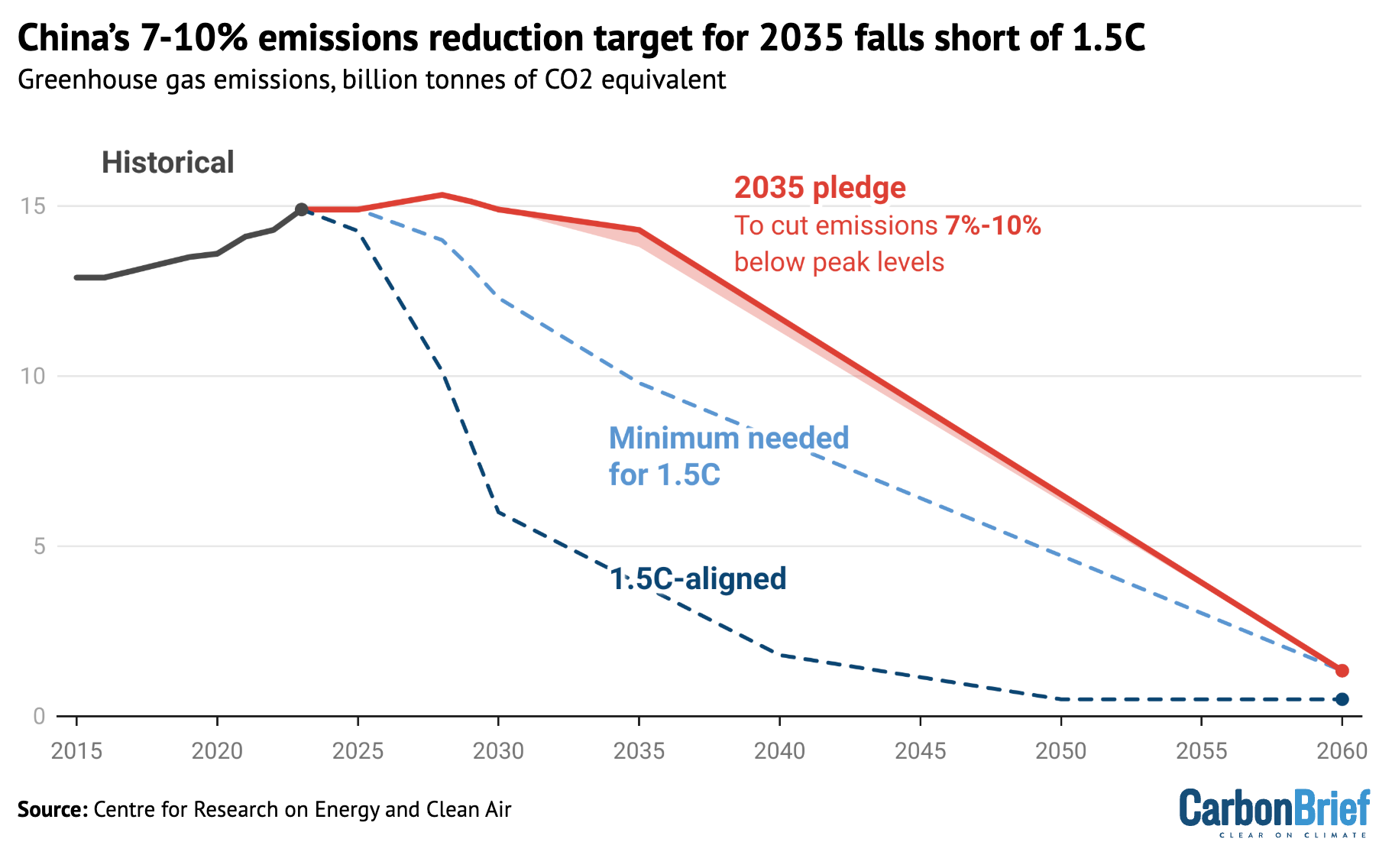

The headline target announced by Xi this week has, nevertheless, been seen as falling far short of what was needed.

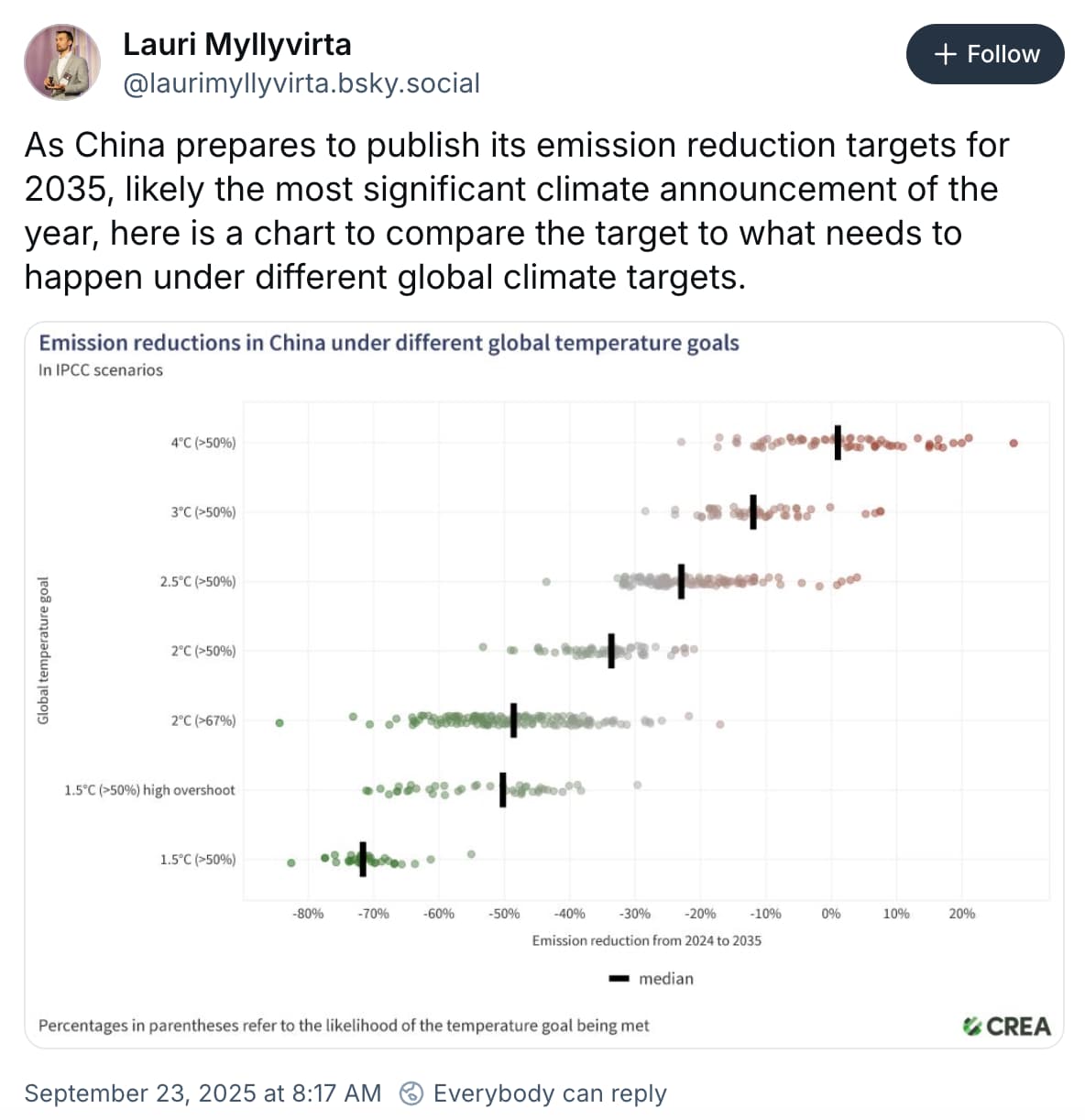

A series of experts had previously told Carbon Brief that a 30% reduction from 2023 levels was the absolute minimum contribution towards a 1.5C global limit, with many pointing to much larger reductions in order to be fully aligned with the 1.5C target.

The figure below illustrates how China’s 2035 target stacks up against these levels.

(Note that the timing and level of peak emissions is not defined by China’s targets. The pledge trajectory is constrained by China’s previous targets for carbon intensity and expected GDP growth, as well as the newly announced 7-10% range. It is based on total emissions, excluding removals, which are more uncertain.)

Analysis by the Asia Society Policy Institute also found that China’s GHG emissions “must be reduced by at least 30% from the peak through 2035” in order to align with 1.5C warming.

It said that this level of ambition was achievable, due to China’s rapid clean-energy buildout and signs that the nation’s emissions may have already reached a peak.

Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said last October that implementing the collective goals of the first stocktake – such as tripling renewables by 2030 – as well as aligning near-term efforts with long-term net-zero targets, implied emissions cuts of 35-60% by 2035 for emerging market economies, a grouping that includes China.

In response to these sorts of numbers, Teng Fei, deputy director of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment and Economy, previously described a 30% by 2035 target as “extreme”, telling Agence France-Presse that this would be “too ambitious to be achievable”, given uncertainties around China’s current development trajectory.

A separate commentary by researchers at the National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC) – a research centre under the Ministry of Ecology and Environment – notes that “certain expectations regarding China’s emissions reduction pathway are unrealistic and unfair”, adding that industrialised nations “historically” saw their emissions plateau for some time after peaking.

It is not clear which expectations the researchers are referring to specifically.

In contrast, a January 2025 academic study, co-authored by researchers from Chinese government institutions and top universities and understood to have been influential in Beijing’s thinking, argued for a pledge to cut energy-related CO2 emissions “by about 10% compared with 2030”, estimating that emissions would peak “between 2028 and 2029”.

(Other assessments have pegged relevant indicators, such as emissions and coal consumption, as peaking in 2028 at the earliest.)

The relatively modest emissions reduction range pledged by Xi, as well as the uncertainty introduced by avoiding a definitive baseline year, has disappointed analysts.

In a note responding to Xi’s pledges, Li Shuo and his ASPI colleague Kate Logan write that he has “misse[d] a chance at leadership”.

Li tells Carbon Brief that factors behind the modest target include the “domestic economic slowdown and uncertain economic prospects, the weakening global climate momentum and the turbulent geopolitical environment”. He adds:

“I also think it is a big psychological jump for the Chinese, shifting for the first time after decades of rapid growth, from essentially climate targets that meant to contain further increase to all of a sudden a target that forces emissions to go down.”

Instead of a target consistent with limiting warming to 1.5C, China’s 2035 pledge is more closely aligned with 3C of warming, according to analysis by CREA’s Lauri Myllyirta.

Climate Action Tracker says that China’s target is “unlikely to drive down emissions”, because it was already set to achieve similar reductions under current policies.

What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

In addition to a headline emissions reduction target, Xi also pledged to expand non-fossil fuels as a share of China’s energy mix and to continue the rollout of wind and solar power.

This continues the trend in China’s previous NDC.

Notably, however, Xi made no mention of efforts to control coal in his speech.

In the full NDC for 2035, China pledges to “strictly control” coal consumption, with a particular focus on “reducing non-power coal use” and “enhancing the clean and efficient” use of the fuel, such as “next-generation” coal-fired power plants. This is largely in line with current domestic coal policy.

In its previous NDC, focused on 2030, China had pledged to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects”, as well as “strictly limit” coal consumption between 2021-2025 and “phase it down” between 2026-2030. It also said China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”.

Notably, the NDC does not reiterate the recommendation from China’s September meeting on its next five-year plan to “promote the peaking of coal and oil” between 2026-2030.

The 2030 NDC also stated that China would “increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25%” – and Xi has updated this to 30% by 2035.

These targets are shown in the figure below, alongside recent forecasts from the Sinopec Economics and Development Research Institute, which estimated that non-fossil fuel energy could account for 27% of primary energy consumption in 2030 and 36% in 2035.

As such, China’s targets for non-fossil energy are less ambitious than the levels implied by current expectations for growth in low-carbon sources.

In a recent meeting with the National People’s Congress Standing Committee – the highest body of China’s state legislature – environment minister Huang Runqiu said that progress on China’s earlier target for increasing non-fossil energy’s share of energy consumption was “broadly in line” with the “expected pace” of the 2030 NDC.

On wind and solar, China’s 2030 NDC had pledged to raise installed capacity to more than 1,200GW – a target that analysts at the time told Carbon Brief was likely to be beaten. It was duly met six years early, with capacity standing at 1,680GW as of the end of July 2025.

Xi has set a 2035 target of reaching 3,600GW of wind and solar capacity.

This looks ambitious, relative to other countries and global capacity of around 3,000GW in total as of 2024, but represents a significant slowdown from the recent pace of growth.

Given its current capacity, China would need to install around 200GW of new wind and solar per year and 2,000GW in total to reach the 2035 target. Yet it installed 360GW in 2024 and 212GW of solar alone in the first half of this year.

In a press conference, a National Energy Administration official said that the NDC targets would require China to make “even greater efforts” in its energy transition. The official noted that it would be important to ensure that additional clean-energy capacity is “dependable”.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief this pace of additions is “not enough to even peak emissions [in the power sector] unless energy demand growth slows significantly”.

But David Fishman, principal at consultancy the Lantau Group, wrote on LinkedIn that China could find it “challenging” to hit this target.

Under the marketised power pricing regulations being rolled out across the country, renewables developers are not incentivised to sustain such high installation figures, he noted, adding: “We’ll be lucky to see 200GW in a single year again for a long time.”

To achieve the 3,600GW target, in his view, China will “need much stronger green power consumption stimulus”.

It could achieve this by ramping up provincial power consumption quotas and setting targets for low-carbon power consumption targets for other energy-intensive sectors.

While the pace of demand growth is a key uncertainty, a recent study by Michael R Davidson, associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, with colleagues at Tsinghua University, suggested that deploying 2,910-3,800GW of wind and solar by 2035 would be consistent with a 2C warming pathway.

Davidson tells Carbon Brief that “most experts within China do not see the [recent] 300+GW per year growth as sustainable”. Still, he adds that the lower levels outlined in his study could be consistent with cutting power-sector emissions 40% by 2035, subject to caveats around whether new capacity is well-sited and appropriately integrated:

“We found that 40% emissions reductions in the power sector can be supported by 3,000-3,800GW wind and solar capacity [by 2035]. Most of the capacity modeling really depends on integration and quality of resources.”

Renewable energy’s share of consumption in China has lagged behind its record capacity installations, largely due to challenges with updating grid infrastructure and economic incentives that lock in coal-fired power.

In Davidson’s study, capacity growth of up to 3,800GW would see wind and solar reaching around 40% of total power generation by 2030 and 50% by 2035.

Meanwhile, China will need to install around 10,000GW of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to a separate report by China’s Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affiliated thinktank.

What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

This is the first time that one of China’s NDC pledges has explicitly covered the emissions from non-CO2 GHGs, such as methane, nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases.

In preparation for a comprehensive greenhouse gas emissions target, China has issued action plans for methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs, one type of F-gas) and nitrous oxide.

According to the NDC, China will aim to “effectively” control methane emissions from energy, agriculture and waste management, including by “utilising” more than 85% of livestock manure by 2035.

It will also promote N2O emissions control in industry and aim to reduce production and consumption of HFCs by at least 30% “relative to baseline levels” by 2035.

By contrast, in China’s 2030 NDC, the country stated it would “step up the control of key non-CO2 GHG emissions”, including through new control policies, but did not include a quantitative emissions reduction target.

The nitrous oxide action plan, published earlier this month, called for emissions per unit of production for specific chemicals to decrease to a “world-leading level” by 2030, but did not set overarching limits.

Similarly, the overarching methane action plan, issued in late 2023, listed several key tasks for reducing emissions in the energy, agriculture and waste sectors, but lacked numerical targets for emissions reduction.

A subsequent rule change in December 2024 tightened waste gas requirements for coal mines. Under the new rules, Reuters reports, any coal mine that releases “emissions with methane content of 8% or higher” must capture the gas, and either use or destroy it – down from a previous threshold of 30%.

But analysts believe that the true challenge of coal-mine methane emissions may come from abandoned mines, which, one study found, have surged in the past 10 years and will likely overtake emissions from active coal mines to become the prime source of methane emissions in the coal sector.

As the demand for coal could be facing a “structural decline”, the number of abandoned mines is expected to grow significantly.

Meanwhile, the HFC plan did set quantitative targets. The country aims to lower HFC production by 2029 by 10% from a 2024 baseline of 2GtCO2e, while consumption would also be reduced 10% from a baseline of 0.9gtCO2e in this timeframe – in line with China’s obligations under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on ozone protection.

From 2026, China will “prohibit” the production of fridges and freezers using HFC refrigerants.

However, the action plan does not govern China’s exports of products that use HFCs – a significant source of emissions.

How does the new NDC talk about global ‘climate cooperation’?

With the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, there has been significant speculation about whether China would fill the resultant “leadership gap”.

Successfully achieving China’s 2035 targets requires an “international political and economic environment conducive to advancing climate action”, according to the NDC text.

Moreover, in what appears to be an oblique reference to the US, it says that “nations undermining international climate cooperation…must bear responsibility”.

Nevertheless, China states that its own “proactive measures to tackle climate change will not slow”, adding that responding to climate change is an “intrinsic” element of its development.

The NDC highlights the role that China’s clean-energy industries have played in “enriching” global supplies of clean-tech and “significantly reducing the cost of the global energy transition”.

It also notes China’s role in initiating platforms such as BASIC and the Ministerial on Climate Action, as well as “numerous” speeches by Xi advocating for sustainable development.

China will “enhance” high-level climate diplomacy, “actively” promoting climate policy in organisations such as G20, BRICS, the World Trade Organization, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Boao Forum for Asia.

It also pledges to “deepen south-south cooperation on climate change”, such as by working with others on “low-carbon demonstration zones”, providing “material donations” and helping developing countries build capacity to address climate change challenges.

However, China does not explicitly state that it will adopt a leading position on climate change at these multilateral forums, saying only that it will “leverage the leading role of leaders in climate diplomacy”.

In addition, China’s NDC calls on developed nations to “fulfil their obligations” in providing climate finance to developing countries, as well as to “achieve net-zero emissions well before 2050”, in order to create “equitable development space for developing nations”.

The NDC reiterates calls against “unilateralism, protectionism and zero-sum thinking”, including “trade barriers” and “climate ‘double standards’” – in what could be referencing the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and duties on imports of Chinese electric vehicles.

What else is in China’s new pledge?

The other quantitative target in the new NDC is to increase forest cover to 24bn cubic metres by 2035 – up 11bn cubic metres from 2005 levels.

In 2024, China’s forest cover stood at more than 20bn cubic metres, according to state broadcaster CGTN. As such, China has already hit its 2030 target of raising forest stock volumes by 6bn cubic metres from 2005 levels.

China also outlines a host of measures for how it will achieve its headline targets, ranging from decarbonising transport to developing “green industry” – largely in line with existing policy.

By 2035, the NDC says, China will have “significantly enhanced” the “innate momentum” of the country’s low-carbon development, allowing the “scale of [clean-energy] industries to reach new heights”.

The NDC also includes a focus on adaptation, stating that China will have “fundamentally established” a climate-resilient society by 2035.

“Monitoring and early warning capabilities” for climate change will reach “advanced” levels and risks from “major climate-related disasters” will be “effectively controlled” under the new plan. Flood controls are specifically mentioned as part of this strategy.

How was Xi’s announcement received?

In a statement, EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra described China’s pledge as “disappointing”, adding that the NDC “makes reaching the world’s climate goals significantly more challenging”.

China’s foreign ministry responded in a written statement to Reuters, saying comments such as Hoekstra’s “disrupts global solidarity in addressing climate change”, adding: “that is what is truly ‘disappointing’”.

“China has led the world in renewable energy investment and deployment”, while the EU’s performance as a “climate leader” has “been uneven and increasingly under strain”, the state-run newspaper China Daily argued in an editorial reacting to Hoekstra’s “irresponsible remarks”.

The state-supporting news outlet Global Times also published an editorial, which, although not mentioning Hoekstra directly, said that the world had “warmly welcomed” China’s target, while “many of Europe’s once-ambitious climate goals have been abandoned or remain unfulfilled”.

(Hoekstra’s comments were made the day after European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said Europe and China are “committed to delivering results” at COP30.)

Former US climate negotiator Sue Biniaz noted in the policy journal Just Security that the “lower than expected” targets “alarmed many in terms of stalling momentum at exactly the wrong time”.

By contrast, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva “welcomed” China’s announcement, Xinhua reported. UNFCCC executive secretary Simon Stiell called the pledge a “clear signal that the future global economy will run on clean energy”.

In a later response to the full NDC, Stiell said the publication of the document is “significant”. However, he also said he “hope[s] that the NDCs we receive will be a floor, not a ceiling for ambition”.

Australian president Anthony Albanese said China’s targets were a “step forward”, although he added he “would like to see no new coal-fired plants open”, ABC News reported.

The three NCSC representatives argue that Xi’s pledge is “grounded in China’s national conditions, stage of development, and long-term strategy”. They add that it aligns with the requirements of the Paris Agreement and global stocktake.

They also say that achieving the new target is “by no means within easy reach” and will require “extraordinary efforts”, a “fair international environment”, as well as “stable” international cooperation.

A number of news outlets, including the Associated Press, Financial Times, Climate Home News, BBC News, Guardian, CNN and Bloomberg, reported that the announcements were criticised for being “conservative” or “weak”.

But in China, reporting on Xi’s speech was largely positive. A commentary in state news agency Xinhua, which was widely reshared by other Chinese news outlets, stated that the commitments “boosted confidence, built consensus and injected new momentum into global climate governance”. Similar messages featured in other outlets’ coverage.

The Communist party-affiliated paper People’s Daily argued that the targets are “in accordance with the Paris Agreement’s requirements and reflecting utmost efforts to enact them”. The article was under the byline Heyin – a nom de plume that indicates the article’s message has been endorsed by party leaders.

A China Environment News commentary said the targets “represent China’s utmost efforts in aligning with the Paris Agreement’s requirements”.

Much of the reporting in China celebrated the NDC for representing a new stage in China’s climate policies.

However, some outlets presented more nuanced coverage. Caixin cited an unnamed “senior climate expert” noting that there was “difficulty and challenges” in devising the goals, given that this was the first time China had set an absolute reduction target.

Coverage by Shanghai-based news outlet the Paper quoted an analyst saying the targets did have “room for greater ambition”.

Meanwhile, multiple analysts noted that China’s pledge stood in sharp contrast to the current US position on climate change.

The Washington Post reported: “The move shows the growing split between the world’s two largest emitters – with the United States reversing its climate policies while China seizes the mantle of green energy leadership.”

However, thinktank E3G said it was likely “worsening tensions with the West and the US retreat from climate leadership” that reinforced Beijing’s decision to pursue more conservative targets.

Indian publication Down to Earth called China’s new targets a “missed opportunity” to signal its “pure dominance” in clean-energy technologies, “particularly as a counter to a climate-denying US”.

Irrespective of the targets’ level of ambition, ASPI’s Li wrote in the New York Times, China’s announcement represented a “wager” that steady action “shielded from political volatility” will be more effective for climate efforts than the “temporary surges in ambition [followed by] political backsliding” seen in the West.