Q&A: What does the VW scandal mean for CO2 emissions?

Simon Evans

11.05.15The Volkswagen (VW) emissions scandal spilled over into climate policy on Tuesday, after the company admitted to “irregularities” in its CO2 testing results.

The firm’s share price — already down 60% after revelations it had deliberately cheated air pollution tests — fell a further 9% by Wednesday morning.

However, the irregularities also have implications for CO2 emissions, as well as UK and EU climate targets. Carbon Brief investigates.

What are CO2 test “irregularities”?

On Tuesday, VW issued a “clarification” about the CO2 emissions testing of up to 800,000 of its vehicles in Europe. The statement says:

During the course of internal investigations irregularities were found when determining type approval CO2 levels…It was established that the CO2 levels and thus the fuel consumption figures for some models were set too low during the CO2 certification process.

Though the precise nature of these problems remains unclear, it has attracted wide media coverage. The Times notes petrol cars have become embroiled in the scandal for the first time. The BBC says the “dirty laundry” is piling up for VW.

The Guardian says VW might have manipulated CO2 tests, in addition to its now-notorious “defeat device” for NOx air pollution. The New York Times says VW’s pollution problems have taken a “costly new turn”. A Guardian live-blog says costs for VW could exceed the €2bn it has set aside.

Current EU regulations limit car CO2 emissions to no more than 130 grammes of CO2 per kilometre, notes Politico. This is set to fall to a fleet-wide average of 95gCO2/km in 2020.

In the UK, vehicle excise duty is linked to CO2 emissions meaning some cars may have had unduly low rates, says Autocar. The Telegraph says some drivers could face higher taxes. However, this year’s budget changed the rules to decouple car tax and CO2 emissions from 2017.

In a press briefing on Wednesday, the European Commission urged VW to clarify “without delay” the kind of irregularities it has found and what has caused them.

So, in short, we still don’t really know what VW is admitting, but we do know that some of its cars have higher emissions than reported. This has been called an “emissions gap”, and it isn’t a new problem.

What is the CO2 emissions gap?

Despite the uncertainty, there is already a lot of information available on car CO2 emissions testing. For instance, it is widely known, in the relevant sectors at least, that there is a growing gap between CO2 emissions recorded in regulatory tests and levels produced by cars in the real world.

This CO2 “emissions gap” has been tracked for several years by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) along with Transport and Environment. The two groups were also behind the emergence of the original “dieselgate” VW emissions scandal for NOx.

The emissions gap affects the entire car and van fleet across Europe, so it runs much wider than VW alone. On average in 2014, new cars emitted 35% more CO2 on the road than they did during lab test cycles, the ICCT says. This gap has risen from 10% in 2002.

The gap is thought to be growing as carmakers increasingly learn how to exploit legitimate aspects of the lab procedure to minimise CO2 emissions during testing.

Dr Peter Mock, managing director for ICCT Europe, tells Carbon Brief:

There are a number of tolerances and flexibilities (aka loopholes) in the current EU type-approval procedure that manufacturers can explore to optimise the CO2 emissions of the vehicles during the laboratory test.

These loopholes include the fact that air conditioning must be switched off during testing and the extra weight cars are carrying is limited. Other flexibilities include the simulated wind resistance during tests and the option to use specially prepared tyres.

Mock says:

Based on a recent analysis of [the ICCT] it appears that these – fully legal – loopholes are sufficient to explain the growing CO2 gap that we observe.

Transport and Environment is more sceptical that the legal loopholes can explain the extent of the emissions gap. In recently published analysis it shows the real-world CO2 emissions for some models from BMW, Mercedes and Peugeot are around 50% above official test figures.

Greg Archer, clean vehicles manager at Transport and Environment, said in a statement a “comprehensive investigation” was needed into whether defeat devices may be in use for fuel economy and CO2 emissions, as well as NOx.

One sector analyst, who did not wish to be named, tells Carbon Brief that VW would not have issued a statement on CO2 “irregularities” if the issue was limited to use of legal loopholes. “This feels like something different,” the analyst says.

What does the scandal mean for national CO2 emissions?

Beyond the level of individual cars, the CO2 gap has implications for total UK and EU transport emissions. However, the VW irregularities on their own may not affect national greenhouse gas inventories. Even the vehicle emissions gap may not change country-level reported CO2 output.

To see why, it’s important to understand that inventories are not based on measured emissions. Rather, they are sophisticated estimates based on the quantities of fuel purchased, the carbon content of that fuel, the types of vehicles on the road and how efficiently they are thought to burn it.

As the UK’s official inventory explains, “emissions of CO2 are closely related to the amount of fuel used”. The gap between CO2 test data for new cars, and real-world emissions, need not be part of this equation.

Official agencies in the UK are looking at potential discrepancies in the UK emissions inventory, Carbon Brief understands. However, while the split of road transport emissions between cars, vans and trucks may change, the total is unlikely to be affected.

What about CO2 targets?

It’s worth noting that despite the growing emissions gap, new cars are still becoming more efficient, with lower CO2 emissions per kilometre than older models. It’s just that cars aren’t becoming more efficient as quickly as they were supposed to, or as quickly as has been claimed.

This is where the emissions gap becomes more important. Future emissions from the transport sector were supposed to fall in line with mandated CO2 standards. Since these standards are not being met, transport is contributing less to carbon reduction targets than was expected.

The UK has legally-binding five-year carbon budgets stretching out towards an 80% emissions reduction in 2050, compared to 1990 levels. As part of this effort, transport emissions are expected to fall from 116m tonnes of CO2 in 2013 to around 69MtCO2 in 2030.

Similarly, under the EU’s 2030 climate and energy goals, transport emissions are supposed to fall by between 11% and 20% in 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

These expected reductions are now uncertain at best, potentially threatening our ability to meet overall carbon targets.

However, the government’s official advisor, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is already on the case. Jack Snape, senior surface transport analyst for the CCC, tells Carbon Brief:

We’ve been aware of the emissions gap issue for a few years and we included it in our analysis of the UK’s fourth carbon budget [2023-2027].

The CCC recently published a report it had commissioned on the problem. The report says:

The UK’s CO2 emission reduction targets are heavily reliant on emissions reductions from new light vehicles [cars and vans]. These reductions are threatened by the growing real-world emissions gap, since UK emissions in future will be significantly higher than predicted by models.

Transport made up 25% of UK emissions in 2013, with cars making up 54% of transport, making car CO2 a significant part of the national total. As emissions fall in line with shrinking future carbon budgets, cars will take an ever-larger share of the pie unless vehicle CO2 standards are effective.

The aim of the report was to understand the reasons for the gap, to see how UK carbon targets might be affected and to check whether a new car testing regime, due to be introduced from 2017, would be sufficient to solve the problem.

Snape tells Carbon Brief the findings are integrated into and explained in more detail as part of the CCC’s advice to government on the UK’s fifth carbon budget for 2028-2032. However, this analysis is not due to be published until 26 November, and he won’t pre-empt that report.

It’s likely, however, that CO2 reduction underperformance in the transport sector will mean greater emissions-cutting effort is expected from other parts of the economy.

At an EU level, Transport and Environment says emissions could be increased by a cumulative 1.5bn tonnes to 2030, as a result of the CO2 emissions gap. The EU is committed to reducing its emissions by “at least 40%” in 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

Assuming the Transport and Environment analysis is correct, the emissions gap could wipe out around 5% of that 40-point reduction. However, this is probably a maximum. Changes to testing procedures and future car efficiency standards for the 2020s could reduce the impact.

Why isn’t CO2 testing more stringent?

The CO2 emissions gap and NOx air pollution scandal are symptoms of long-standing problems with the vehicle testing regime, known as NEDC (new European driving cycle). In response, a new test procedure is being introduced called WLTP (worldwide harmonised light vehicle test procedure). This is supposed to be more realistic, with test conditions closer to those in the real world.

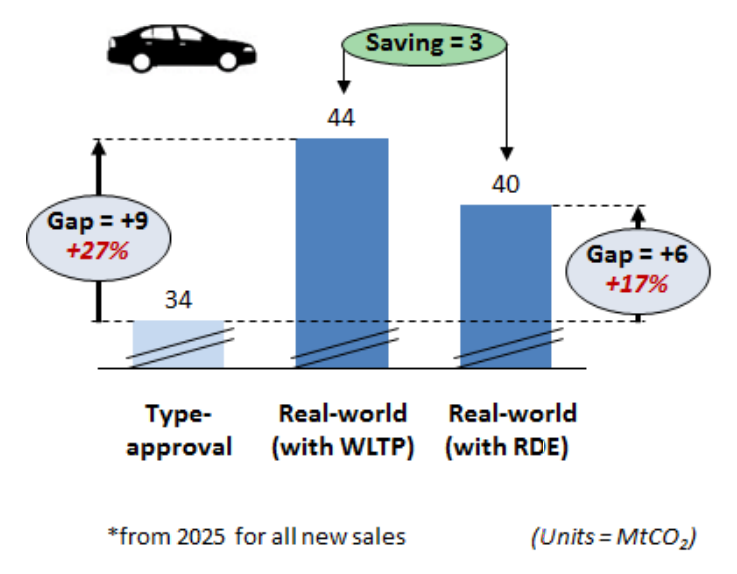

Unfortunately, the CCC’s report shows WLTP will only shrink the emissions gap in 2030, rather than closing it entirely. The chart below illustrates its findings for cars, where a 9MtCO2 emissions gap will remain in 2030 under the new WLTP test procedure. Even a more stringent testing based on real driving emissions (RDE) will not completely close the emissions gap, it shows.

Left to right: UK car emissions in 2030 if new models performed as they are supposed to (type-approval); under real-world conditions with the WLTP updated test regime; and under an enhanced real driving emissions (RDE) testing regime. Source: CCC.

Some media reports suggest governments are lobbying to get the new WLTP regime watered down. One way or another, it is likely a vehicle CO2 emissions gap will remain in 2030. That’s despite calls from large investors, for the European Commission to toughen the car testing regime.

The CCC’s Snape tells Carbon Brief the continuing gap should be taken into account by the European Commission when it proposes new CO2 standards for vehicles in 2017. The standards would kick in from 2025.

Snape says:

We’re very keen those [2025 standards] are set with the knowledge that testing can be manipulated. You really need very stretching targets…that factor in that [emissions] gap.

Among other things, a more stretching target would force greater efforts towards vehicle electrification, he says, where CO2 emissions are hard to manipulate.

Christiana Figueres, the UN climate chief, says a stronger focus on electrification could be a silver lining of the VW scandal. Indeed, VW has said it will expand production of electric and hybrid cars as a result of recent revelations about its behaviour.

5/11 – We corrected the figure for UK transport emissions, which were 116MtCO2 in 2013.

6/11 – We added news that a group of large investors are calling on the European Commission to toughen car emissions testing.