Q&A: What the ‘controversial’ GWP* methane metric means for farming emissions

Orla Dwyer

10.03.25Orla Dwyer

03.10.2025 | 1:09pmA controversial way of measuring how much methane warms the planet has stirred debate in recent years – particularly around assessing the climate impact of livestock farming.

The metric – known as GWP* (global warming potential star) – was designed to more precisely account for the warming impact of short-lived greenhouse gases, such as methane.

No country so far has used GWP* to measure emissions, but New Zealand is currently considering its use.

In June, a group of climate scientists from around the world wrote an open letter advising against this.

They argued that the metric “creates the expectation that current high levels of methane emissions are allowed to continue”.

Climate experts tell Carbon Brief that there is “no strong debate” on the science behind GWP* and that it can accurately assess the global warming effect of methane.

But many experts also firmly caution against its use in national climate targets, believing it could allow countries to prolong high levels of emissions at a time when they should be drastically cut.

Some researchers tell Carbon Brief that GWP* is an “accounting trick” and a “get-out-of-jail-free card for methane emitters”. A 2021 Bloomberg article called the metric “fuzzy methane math”.

Prof Myles Allen, one of the scientists who created GWP*, tells Carbon Brief that the metric is “nothing more” than one way of better understanding the climate impact of different actions as part of efforts to limit warming under the Paris Agreement.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explains the science behind GWP*, why the metric is so divisive and the ways in which its use has been considered.

- What is GWP*?

- What are the main controversies around using GWP*?

- Do any countries currently use GWP* to measure methane emissions?

- What do experts think about the use of GWP*?

What is GWP*?

Global warming is caused by a build up of greenhouse gases – mainly from burning fossil fuels – trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Different gases cause differing levels of warming and remain in the atmosphere for varying lengths of time. For example, carbon dioxide (CO2), the main contributor to warming, lingers for centuries, whereas other gases last decades or even millennia.

To account for these variables, scientists use a metric known as global warming potential (GWP), which assesses the warming caused by different gases compared to CO2, which has a GWP of 1.

Using GWP, emissions of other gases are calculated in terms of their “CO2 equivalent” over a given amount of time.

In their reports, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) set out three GWP variants measured over 20 years (GWP20), 100 years (GWP100) and 500 years (GWP500).

GWP100 is the most common approach and is used to calculate emissions under the Paris Agreement.

Methane is a short-lived gas that only remains in the atmosphere for around 12 years before breaking down. But it causes a large burst of initial warming that is around 80 times more powerful than CO2, according to the IPCC.

This means that one tonne of methane causes the same amount of warming as around 80 tonnes of CO2, when measured over a period of 20 years.

When calculated over 100 years, methane’s shorter lifetime means it causes around 30 times more warming than CO2.

Some experts have criticised the use of GWP100, saying it does not sufficiently account for the fact that methane leaves the atmosphere much more quickly than CO2 and does not actually last for 100 years. This is the issue that GWP* was designed to fix.

GWP* calculates the warming contributions of long- and short-lived gases at different rates, accounting for their varying lifetimes in the atmosphere.

One of the researchers behind GWP*, Dr Michelle Cain, explained in a 2018 Carbon Brief guest post that a constant rate of methane emissions can maintain stable atmospheric concentrations of the gas, assuming methane sinks remain constant as well.

In contrast, a constant rate of CO2 emissions “leads to year-on-year increases in warming, because the CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere”, Cain wrote. CO2 does not leave the atmosphere after a decade or so, as methane does, and continues to build over time until emissions stop.

Cain, formerly a researcher at the University of Oxford and now a senior lecturer at Cranfield University, added:

“For countries with high methane emissions – due to, say, agriculture – this can make a huge difference to how their progress in emission reductions is judged.”

Methane emissions that slowly decline or remain stable over time are calculated as contributing “no additional warming” to the planet, which is not the case with other GWP calculations.

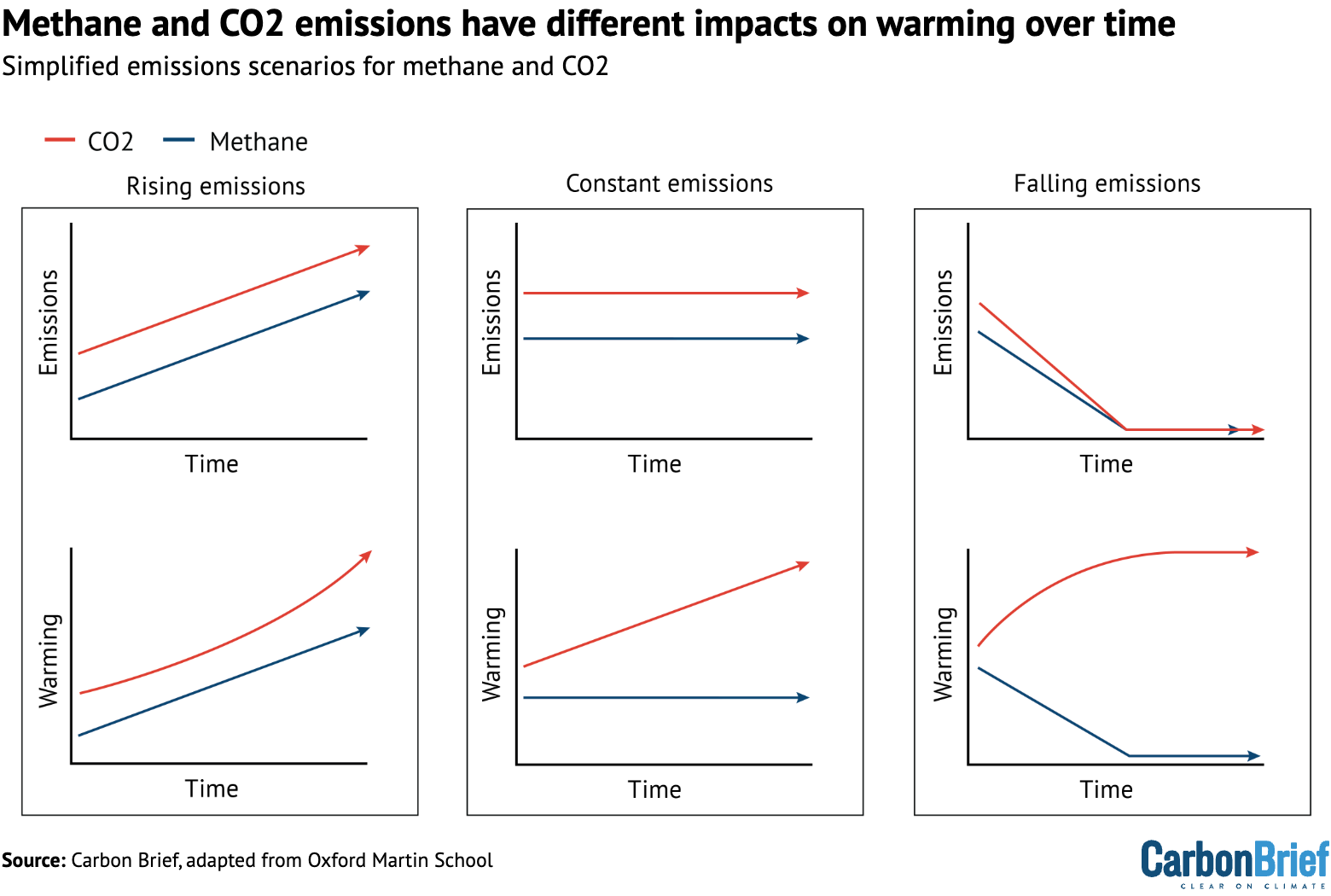

The chart below shows simplified emissions scenarios for CO2 and methane, highlighting the different impacts they have on global warming over time.

The chart below shows how using the two different metrics – GWP* and GWP100 – affects the same emissions pathway throughout the 21st century, given the different warming impacts of greenhouse gases.

If, for example, a country emitted 4m tonnes of methane annually from 1990-2005, these emissions would now be considered “climate-neutral” using GWP*, as they are not actively contributing new warming to the atmosphere, but rather maintaining the existing levels of methane in the atmosphere in 1990.

This would not be the case under GWP100, which looks at the warming potential of emissions over the course of a century and does not account for their different atmospheric lifetimes.

GWP* can be used for other short-lived gases, such as some hydrofluorocarbons, but methane is the most significant short-lived gas when it comes to climate change.

The IPCC notes that converting methane emissions into CO2 equivalent using GWP100 “overstates the effect of constant methane emissions on global surface temperature by a factor of 3-4” and understates the impact of new methane emissions “by a factor of 4-5 over the 20 years following the introduction of the new source”.

GWP* was created by several researchers, including Prof Myles Allen, the head of atmospheric, oceanic and planetary physics at the University of Oxford. The concept was detailed in a 2016 study and first named in a 2018 study. It was further updated by the authors in 2019 and 2020.

Allen tells Carbon Brief that the researchers involved were “reluctant” to give their new metric a name, as it “was just a way of using reported numbers to calculate warming impact”. He adds:

“I think it’s really unfortunate that people have latched onto GWP*. It doesn’t matter. We could forget about GWP* entirely, we can just use a climate model to work out the warming impact…GWP* is a handy way of calculating the warming impact of activities. Nothing more.”

What are the main controversies around using GWP*?

Efforts to cut methane emissions are widely viewed as a “quick-win” to help limit the effects of climate change in the short term.

More than 100 countries signed a pledge, launched at COP26 in 2021, to cut global methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

Cutting methane would also help to counteract an acceleration in warming due to declining aerosol emissions, which are currently masking around half a degree of warming.

Experts Carbon Brief spoke to agree on the importance of cutting methane emissions, but disagree on whether GWP* helps or hinders these efforts.

The debate around the metric centres on the possible impacts of its use, rather than the soundness of the science behind it.

Prof Joeri Rogelj, a climate science and policy professor at Imperial College London, explains:

“At the global level, at any level, the method of GWP* actually provides a good, new way to translate the trajectory of methane emissions into equivalent emissions of CO2, or emissions of CO2 that would have an equivalent warming effect…The debate is on the application.”

Allen says he is a “little frustrated” that discussions around the use of GWP* have “become so emotive”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Every action we take has both a temporary impact on global temperature and a permanent one. How much is in both areas depends on the action. We need to know those two things in order to make decisions about choices of action in pursuit of a temperature goal…GWP* gives you a handy way of doing that.”

Below, Carbon Brief details some of the main discussion points and controversies around GWP*.

Carbon cycle

A misleading claim frequently made about livestock is that cows do not contribute much to global warming because the methane they emit eventually returns to the land through the carbon cycle – the set of processes in which carbon is exchanged between the atmosphere, land and ocean, as well as the organisms they contain.

Those in favour of using GWP* to measure methane emissions often also stress the difference between methane emissions that come from animals – known as biogenic methane – and methane from fossil fuels.

Rogelj tells Carbon Brief that biogenic and fossil-sourced methane are “slightly different, but that difference is really second-order” when it comes to climate change.

Methane warms the planet while it is in the atmosphere, so the “climate effect is exactly the same, irrespective of which source the methane comes from”, Rogelj adds.

The differences become more significant when methane breaks down in the atmosphere and oxidises into water vapour and CO2.

CO2 that originated from a cow can be reabsorbed by plants and the land. But the CO2 resulting from fossil methane – which stems from sources such as flaring from oil and gas drilling – stays in the atmosphere. Although fossil methane has a “bit of a longer effect”, Rogelj says:

“This is a bit of a red herring, because the main effect is, of course, the effect that the methane has while it is methane and not what the carbon molecule of that methane has after [the] methane has been broken down or oxidised to CO2.”

He adds that there are ways of reducing agricultural methane, such as “diet change” or “management measures”, but no way to remove the emissions “100%”.

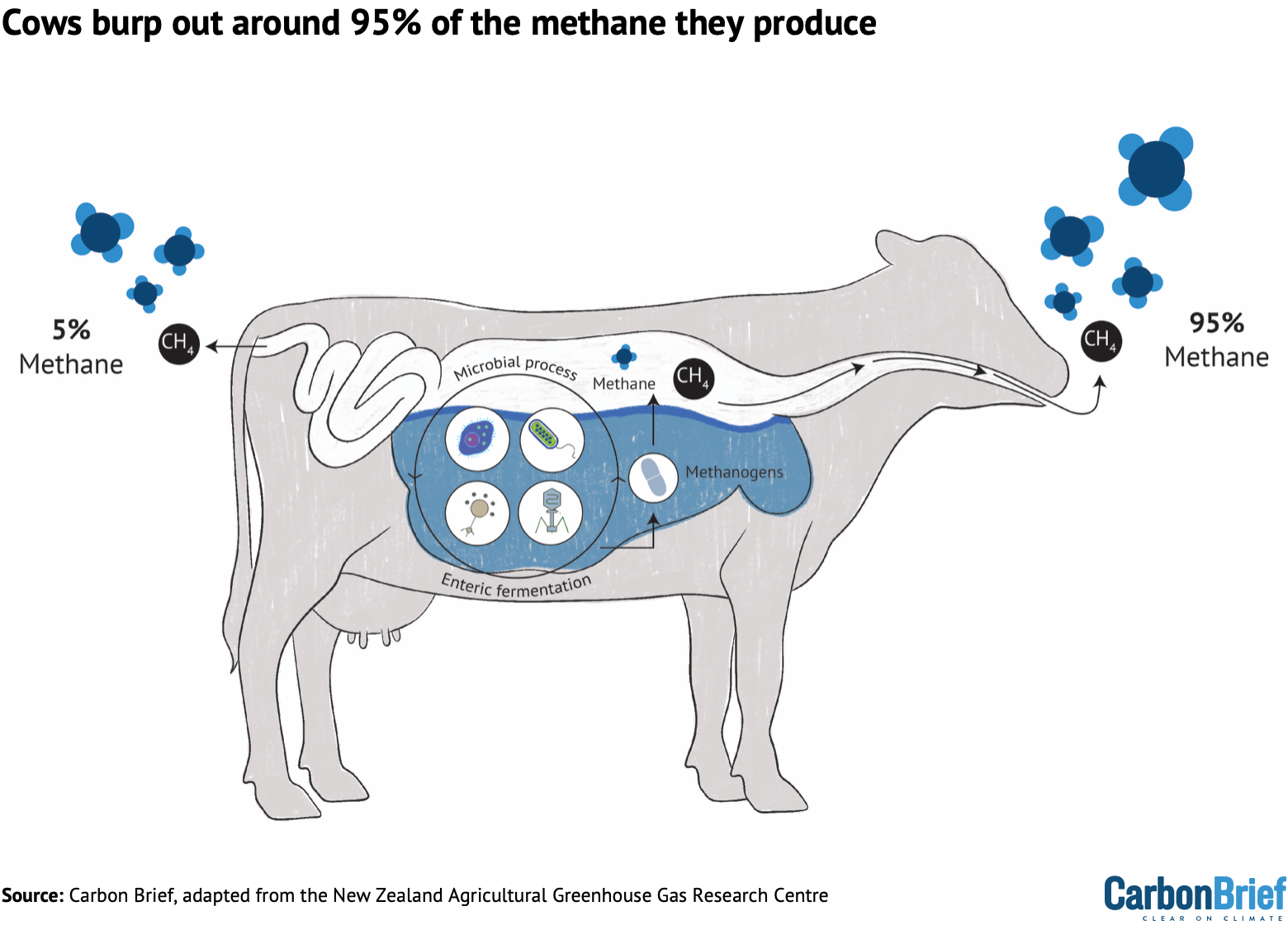

The graphic below shows the digestive process through which a cow emits methane.

Agriculture also causes other significant environmental harms. It is responsible for around 80% of global deforestation and is a key driver of biodiversity loss and water pollution.

Prof Frank Mitloehner, a professor and air-quality specialist at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), is one of the main proponents of GWP*, frequently speaking about it in public presentations and discussions with the farming sector.

He tells Carbon Brief that, while animal agriculture can cause environmental harm, it is a “silly argument” to say these impacts are being ignored in carbon-cycle discussions.

He gives an example of discussions on deaths from car accidents excluding mentions of the emissions from cars, saying that these wider impacts are still important and can be discussed separately.

He adds that it is an “urban myth” that biogenic methane emissions are not a concern because of the carbon cycle.

‘No additional warming’

Under GWP*, methane emissions stop causing new warming once they reduce by 10% over the course of 30 years – around 3% each decade, or 0.3% each year.

These emissions are then described in research and policy as causing “no additional warming”.

For example, a 2021 study from Mitloehner and other UC Davis researchers, found that methane emissions from the US cattle industry “have not contributed additional warming since 1986”, based on GWP* calculations. It also said that the dairy industry in California “will approach climate neutrality” by the 2030s, if methane emissions are cut by just 1% annually.

(According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, methane emissions from enteric fermentation – the digestive process through which cows produce the greenhouse gas – increased by more than 5% over 1990-2022.)

However, many critics take issue with the “no additional warming” concept.

The main criticism is that, although a gradually reducing herd of cattle may stabilise methane emissions, it still emits the polluting gas. If animal numbers were instead drastically reduced, this would cut methane emissions and lower warming rather than maintaining current levels.

Dr Caspar Donnison, a postdoctoral researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US, says the term no additional warming is “absolutely misleading” in the context of GWP*. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You just assume, on the face of it, that this means it has a neutral impact on the climate…But ‘no additional warming’ means that you’re still sustaining the warming that the herd is causing.”

Allen says that the debate focuses on the “stock of warming versus additional warming”. He compares it to accounting for historical emissions of CO2:

“If a country got rich by burning CO2, they’ve caused a lot of warming in the past. If they reduce their CO2 emissions to zero, then people are generally happy to call what they’re doing climate-neutral, even though they may be sitting on a huge heap of historical warming caused by their CO2 emissions while they were burning [fossil fuels].

“And yet, temperature-wise, that’s exactly the same thing as having a source of methane that’s declining by 3% per decade.”

Climate ambition

Another criticism around the use of GWP* is that countries or companies with high agricultural methane emissions could use the metric to make small emission reductions appear larger.

Dr Donal Murphy-Bokern, an independent agricultural and environmental scientist, believes that the metric can be used as a “get-out-of-jail-free card for methane emitters”. He adds:

“It’s all about saying carry on as we are; we’ll manage this by slightly reducing our emissions over a critical period in history, so as to appear at that critical period in history to be so-called ‘climate-neutral’.”

Mitloehner disagrees with this, noting that, while reductions in methane emissions appear significant under GWP*, increases also appear significant. He says:

“It is simply not true that GWP* is a get-out-of-jail-free card. It’s not. If you reduce emissions, it makes your contributions look less. If you increase emissions, it makes your contributions much worse.”

Rogelj says he has not seen GWP* being used to advocate for the “highest possible ambition” in cutting methane emissions.

However, Allen says that “no metric tells you what to do”. He adds:

“How you measure emissions and how you measure warming has absolutely no bearing on whether you think a country has an obligation to undo some of the damage to the climate they’ve caused in the past.

“This is where the ‘free-pass’ argument makes no sense to me, because the existence of a method to calculate the warming impact of your emissions allows you to make decisions about emissions in light of their warming impact, sure, but it doesn’t tell you what the outcomes of those decisions should be.”

Allen adds that the livestock sector is “unsustainable globally”, with animal numbers and methane levels still rising.

The chart below shows how atmospheric methane concentrations have increased in recent decades.

Allen tells Carbon Brief:

“Do we need to eliminate livestock agriculture to stop global warming? No…[but] we do need to start decreasing it. And if we can decrease it faster than 3% per decade then that would help reduce warming that’s caused by other sectors or, indeed, undo some of the warming that the livestock sector has caused in the past.”

Mitloehner says considerations on the fairness of using GWP* are “real from a policy standpoint and they have to be addressed from a policy standpoint”. He adds:

“But, from a scientific standpoint – and that’s where I’m coming from – I think it’s not controversial.”

Baseline and historical emissions

The baseline year from which emissions reduction targets are set is significant, as it helps form the scope of climate ambition.

For example, high-emitting countries, such as the UK, have set 1990 as their baseline year for emissions-cutting targets, whereas many low-emitting countries may choose further back or more recent years, depending on their needs. Rogelj says:

“Because GWP* translates a change in emissions into either an instantaneous emission or instantaneous removal of CO2, your starting point becomes really important.

“If you start with very high emissions of methane and you did not in any way account for this high starting point, then even very minor, unambitious reductions in methane would result in creating credits for high-polluting countries.”

However, he notes that this is just one way of applying the metric and that there could be ways to avoid this “inequitable outcome”, such as applying GWP* globally and allocating each country a per-capita methane budget, instead of assessing based on national current or past emissions. (Rogelj and Prof Carl-Friedrich Schleussner discussed other possible GWP* equity measures in a 2019 study.)

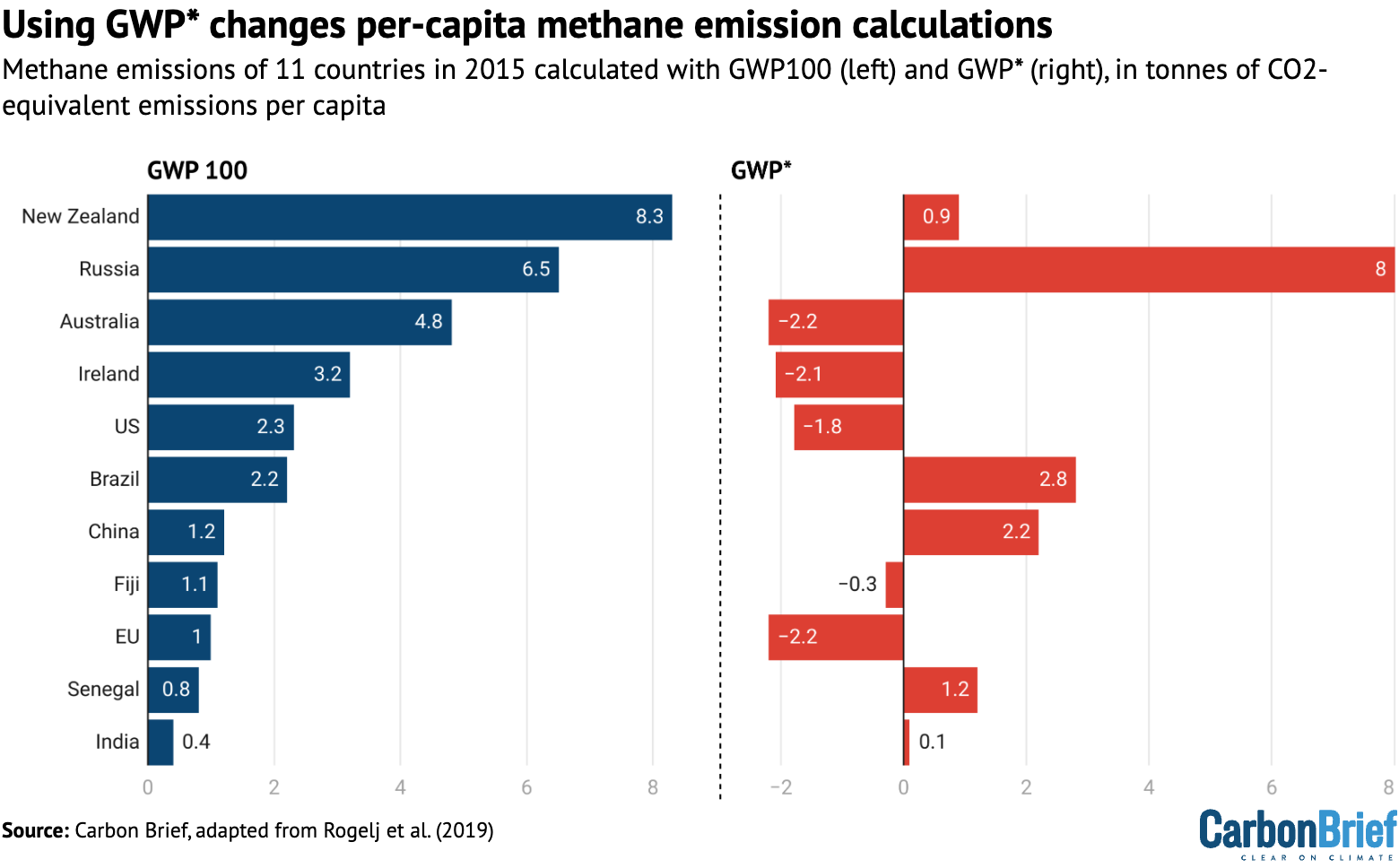

The chart below, adapted from that study, shows how GWP* can significantly change the per-capita methane emissions of different countries. Some countries with high agricultural methane emissions, such as New Zealand, change from high to low per-capita emitters.

A 2025 study used a climate model to quantify future national warming contributions for Ireland under different emissions scenarios and found that “no additional warming” approaches, such as GWP*, are “not a robust basis for fair and effective national climate policy”.

Discussing baseline concerns, Allen says these considerations are the same for any other metric:

“It depends on how much account you want to take of [the] warming you’ve caused in the past – and at what point you want to take responsibility for the warming your actions had caused.”

He believes that most climate experts agree that it is good to understand the impact emissions have on global temperatures, but “where the controversy arises is about what you consider someone’s nominal emissions to be today”. He adds:

“This is where everybody gets upset, because if you use GWP*, then a livestock sector that’s reducing its emissions by 3% per decade – which most global-north livestock sectors are doing – it looks like their emissions are quite small.

“But that’s only a problem if you think that the main issue is working out whose fault global warming is, rather than working out what we should do about it.”

Communication

Many experts Carbon Brief spoke to took issue with how GWP* has been discussed by some of its proponents.

Murphy-Bokern criticises how Mitloehner and other experts communicate the metric. He says:

“The confusion arises from the activities of Mitloehner, in particular, where he presents the farming community – and the industry in general – with the idea that you can magic away the warming effect of methane simply by looking at the rate of change of methane emissions.”

Mitloehner says he has no regrets about his communication of GWP*, adding that he has “always emphasised to the livestock sector that reductions of methane are important”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I’m proud because I have been able to take the livestock sector along with the understanding that reductions are needed and that they can be part of a solution if they understand that.”

The New York Times reported in 2022 that the research centre led by Mitloehner at the University of California, Davis “receives almost all its funding from industry donations and coordinates with a major livestock lobby group on messaging campaigns”. Other reports note his discussions about GWP* with stakeholders in various countries.

In response to these reports, Mitloehner says he believes it is important to work with the sector you are researching, adding that he receives both public and private funding. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The problem is not that they [the meat industry] are investing in research and communications and extension. The problem is that they are not putting in enough, because the public sector is withdrawing from this.

“Climate research is being slashed…If the government is not paying into research to quantify and reduce emissions – and those people who are critical of what we do say ‘oh, industry shouldn’t do it’ – then, I ask you, who should?”

Colin Woodall, the chief executive of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a US lobby group, said in 2022 that GWP* is the “methodology we need to make sure everybody is utilising in order to tell the true story of methane”, Unearthed reported. According to the outlet, he added:

“We’re working with our partners around the globe to ensure that everybody is working towards adoption of GWP*.”

Asked if he regrets anything about his communication of GWP*, Allen tells Carbon Brief:

“When we first introduced this – and, perhaps, this is one thing I do regret – I was, perhaps, a little naive in that I thought everybody would seize on focusing on [the] warming impact because it was, from a policy perspective, potentially much easier for the agricultural sector.

“I thought that this would actually be welcomed. But, sadly, it’s not been. And I think part of that is because of this narrative of blame.”

Do any countries currently use GWP* to measure methane emissions?

GWP* is not yet used by any country in methane emission reporting or targets. But it has been considered by New Zealand, Ireland and other nations with high agricultural emissions.

A 2024 statement from dozens of NGOs and environmental organisations called for countries and companies not to use GWP* in their greenhouse gas reporting or to guide their climate mitigation policies. They wrote:

“The risks of GWP* significantly outweigh the benefits.”

New Zealand

New Zealand is currently considering changing its biogenic methane target, including applying the “no additional warming” approach used in GWP*. If it does so, it could become the first country to adopt GWP*.

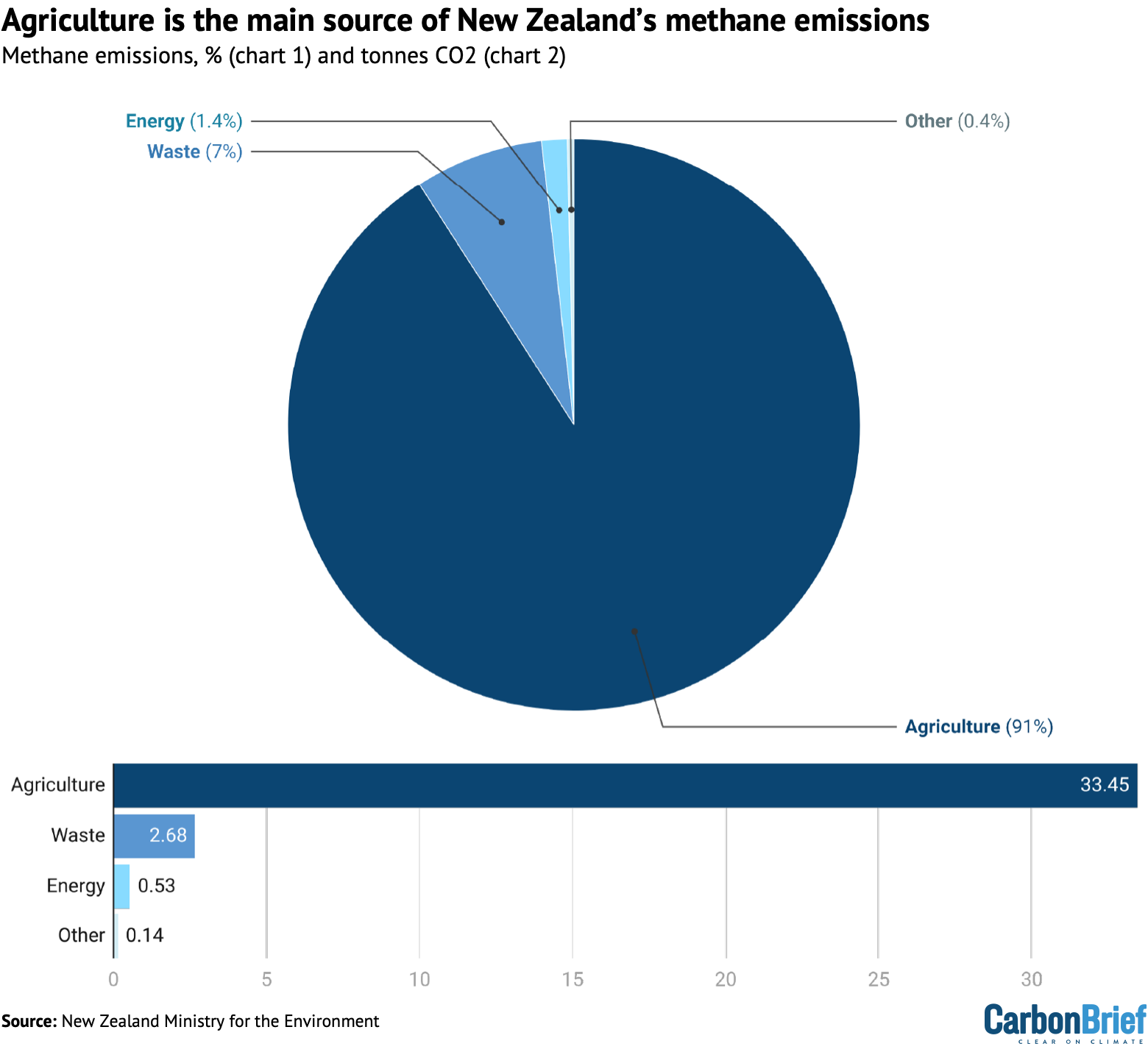

The nation is a major livestock producer and agriculture generates nearly half of all its greenhouse gas emissions.

The chart below shows that the agricultural sector is also responsible for more than 90% of the country’s methane emissions.

New Zealand has a legally binding target to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, biogenic methane has separate targets to reduce by 10% by 2030 and by 24-47% by 2050, compared to a baseline of 2017 levels.

In late 2024, a review from the nation’s Climate Change Commission recommended that the government change its 2050 greenhouse gas targets, including to increase the biogenic methane goal to a 35-47% reduction by 2050.

At the same time, an independent panel commissioned by the New Zealand government reviewed how the country’s climate targets would look under the “no additional warming” approach.

The resulting report, which did not look specifically at GWP*, but used a similar concept, found that a 14-15% cut in biogenic methane by 2050 would be “consistent with meeting the ‘no additional warming’ condition”, under mid-range global emissions scenarios that keep temperatures below 2C.

The government is “currently considering” these findings, a spokesperson for the Ministry for the Environment tells Carbon Brief in a statement.

The spokesperson says that the report is “part of the body of evidence” that the government will use in its response to the Climate Change Commission’s review, which it must publish by November 2025.

Cain, the Cranfield University lecturer who co-created GWP*, wrote in Climate Home News in 2019 that New Zealand reducing biogenic methane by 24% would “offset the warming impact” of the rest of the country’s emissions, adding:

“New Zealand could declare itself climate-neutral almost immediately, well before 2050 and only because farmers were reducing their methane emissions. That’s a free pass to all the other sectors, courtesy of New Zealand’s farmers.”

A report on GWP* by the Changing Markets Foundation found that, in 2020, 16 industry groups in New Zealand and the UK “urged” the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to use GWP* to assess warming impacts.

Australia

The Guardian reported in May 2024 that Cattle Australia, a cattle producer trade group, was “lobbying the red-meat sector to ditch its net-zero target in favour of a ‘climate-neutral’ goal that would require far more modest reductions in methane emissions”.

Cattle Australia’s senior adviser and former chief executive, Dr Chris Parker, tells Carbon Brief in a statement that the organisation is “working with the Australian government to ensure methane emissions within the biogenic carbon cycle are appropriately accounted for in our national accounting systems”. He adds:

“We believe GWP* offers a more accurate way of assessing methane’s temporary place in the atmosphere and its impact on the climate. Australian cattle producers are part of the climate solution and we need policy settings to enable them to participate in carbon markets.”

Australia’s Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water did not respond to Carbon Brief’s request for comment.

Ireland

Internal documents assessed for the Changing Markets Foundation’s GWP* report “suggest” that Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine has advocated for GWP* “at the international level”, including at the UN’s COP26 climate summit in 2021.

Allen and Mitloehner were involved in a 2022 Irish parliamentary discussion on methane, in which Allen advocated for the country to “be a policy pioneer” by using GWP* in its methane reporting alongside standard methods.

The country’s coalition government, formed earlier this year, pledged to “recognise the distinct characteristics of biogenic methane” and also “advocate for the accounting of this greenhouse gas to be re-classified at EU and international level”.

A spokesperson for Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine tells Carbon Brief that this does not refer to using GWP* specifically. They say the country is “in favour of using accurate, scientifically validated and internationally accepted emission measurement metrics”, adding:

“It is important that the nature of how biogenic methane interacts in the environment is accurately reflected in how it is accounted for. This does not mean the use of the metric GWP*.”

In December 2024, Ireland’s Climate Change Advisory Council proposed temperature neutrality pathway options to the government that do not specifically refer to GWP*, but use the same concept of no “additional warming”.

The Irish Times reported that this was “in part to reduce potential disruption from Ireland’s legal commitment to achieve national ‘climate neutrality’ by 2050”.

The climate and energy minister, Darragh O’Brien, said he has “not formed a definitive view” on this, the newspaper noted, and that expert views will feed into ongoing discussions on the 2031-40 carbon budgets, which are due to be finalised later in 2025.

In an Irish Times opinion article, Prof Hannah Daly from University College Cork, described the temperature neutrality consideration as “one of the most consequential climate decisions this government will make”. She wrote that the approach “amounts to a free pass for continued high emissions” of livestock methane.

Paraguay

Paraguay mentioned GWP* in a national submission to the UN in 2023 after agribusiness representatives “pushed” to adopt the metric, according to Consenso, a Paraguayan online newsletter.

The country’s National Directorate of Climate Change told Consenso for a separate article related to GWP* that it is “aware” of questions around the metric, but that it “has the option of using other measurement systems” for emissions reporting.

UK

The National Farmers’ Union, the main farming representative group in England and Wales, is in favour of using GWP* to measure agricultural methane emissions.

Carbon Brief understands that the UK government is not currently considering using GWP* in addition to, or instead of, GWP100 in its emissions reporting.

What do experts think about the use of GWP*?

Most experts Carbon Brief spoke to agreed that GWP* could be a useful metric to apply to global methane emissions, but that it is difficult to apply equitably in individual countries or sectors. Rogelj believes that are are some contexts in which GWP* could be used, but adds:

“You cannot just take targets that were set and discussed historically with one greenhouse gas metric in mind – GWP100 under the UNFCCC [United Nations Framework on Climate Change] and the Paris Agreement and all that – [and] then simply apply a different metric to it. They change meaning entirely.

“So, if one would like to use GWP*, one should build the policy targets and frameworks from the ground up to take advantage of the strengths of that metric, but also put in place safeguards that ensure that the weaknesses and limitations of that metric do not result in unfair or undesirable outcomes.”

A 2022 study says that using GWP* in climate plans “would ask countries to start from scratch in terms of their political target setting processes”, calling it a “bold ask” for policymakers.

It adds that achieving net-zero emissions, as measured with GWP*, “would only lead to a stabilisation of temperatures at their peak level”.

However, a 2024 study found that GWP* gives a “dynamic” assessment of the warming impact of emissions that “better aligns with temperature goals” than GWP100, when measuring methane emissions from agriculture.

Allen believes that criticism over the use of GWP* is similar to “saying it’s a meaningless question” to consider the warming impact of a country or company’s actions. He adds:

“That seems a very strange position to me, because we need to know how different activities are contributing to global warming because we have a temperature target.

“In saying GWP* is a bad thing, what people are actually saying is it’s a bad thing to know the warming impact of our actions, which is a very strange thing to say.”

He says that such metrics help countries to make informed decisions on climate action, but that “we can’t expect metrics to make these decisions for us”.

Murphy-Bokern notes that GWP* could be useful in modelling global, rather than national, methane emissions to avoid high-emitting countries making small methane cuts to achieve “no additional warming”, rather than significantly reducing these emissions.

He says the metric would be particularly useful if global emissions were close to zero, as a way to target the final remaining emissions. But, he adds:

“We are so far away from that very happy situation, that the discussion now with GWP* is a huge distraction from the key objective, which is to reduce emissions.”

Mitloehner – and every expert Carbon Brief spoke with – agrees with this wider point. He says:

“The main point is we need to reduce emissions. In the case of livestock, we need to reduce methane emissions. And the question is how do we get it done? And how do we quantify the impacts that [that reduction] would have accurately and fairly? The other issues are issues that politicians have to answer.”