Revealed: UK development body still has $700m invested overseas in fossil-fuel assets

Josh Gabbatiss

05.16.25Josh Gabbatiss

16.05.2025 | 11:51amBritish International Investment (BII), a UK government-owned and aid-funded company, has a portfolio of overseas fossil-fuel assets worth hundreds of millions of dollars, Carbon Brief can reveal.

In 2020, BII committed to “aligning” its “future” investments with the Paris Agreement and since then it has doubled its renewable-energy funding.

But, as of 2023, the last year for which data is available, it also still had a large portfolio of gas-fired power plants across Africa and south Asia.

Multiple freedom of information (FOI) requests by Carbon Brief reveal fossil-fuel energy and related projects worth nearly $700m (£526m) on BII’s books, which represents about 6% of its assets in 2023.

The FOI results also show that, at the end of last year, BII still had $70m (£53m) of unspent funds earmarked for foreign fossil-fuel companies in the coming years.

BII has not breached its own investment guidelines and says its fossil-fuel exposure fell further in 2024 as it aims to “manage and responsibly exit” these assets.

However, MPs and campaigners have criticised BII’s legacy fossil-fuel investments for “conflicting” with UK climate goals and diverting increasingly scarce aid resources.

Climate pledge

BII is the UK’s development finance institution (DFI), a publicly owned, for-profit company that invests in businesses in developing countries.

These investments are meant to promote economic development, especially via projects – including new energy infrastructure – deemed “too risky” for private investors.

BII largely supports itself using financial returns from its existing portfolio, which was worth approximately £7.3bn ($9.2bn) in 2023.

However, the UK government has also provided BII with billions of pounds from its aid budget. This support has grown even amid massive cuts to UK aid, with BII receiving an extra £400m last year due to reduced government spending on housing asylum seekers.

The government has also been leaning more on BII to reach its international climate finance goals.

Despite being wholly owned – and partly funded – by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), BII has an “arm’s length” relationship with the UK government and makes its own investment decisions.

In 2020, the previous Conservative government committed the UK to ending new overseas fossil-fuel funding beyond March 2021.

This came after BII – then known as CDC Group – had pledged in its 2020 climate strategy that it would not make any new investments that were “misaligned with the Paris Agreement”, based on a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures framework.

Then-chief executive Nick O’Donohoe stated that the climate strategy would “shape every single investment decision we make moving forward”.

This was hailed as an end to fossil-fuel financing by the institution, despite some remaining “loopholes”. Notably, its fossil-fuel policy allowed for new investments in gas projects if they were deemed “consistent with a country’s pathway to net-zero by 2050”.

Since making its pledge, BII has repeatedly come under fire from MPs and campaigners for continuing to hold “active investments” in fossil-fuel companies.

Fossil assets

BII says that its fossil-fuel portfolio, which mainly consists of gas-fired power plants in “power-constrained” African nations, “has been on a steady downward trajectory since 2020”.

However, the company has not released data on the value of its fossil-fuel assets since 2021, citing “commercial sensitivities”.

In September 2024, Carbon Brief filed an FOI request with BII to obtain data on the company’s fossil-fuel and renewable-energy investments, as well as their asset value.

Following more than six months of back-and-forth – including Carbon Brief requesting an internal review of its FOI request – the company provided much of the information that was originally requested at the end of March 2025.

This included annual data on projects that BII has already committed to support, such as the Sirajganj 4 gas plant in Bangladesh and the Amandi Energy gas plant in Ghana.

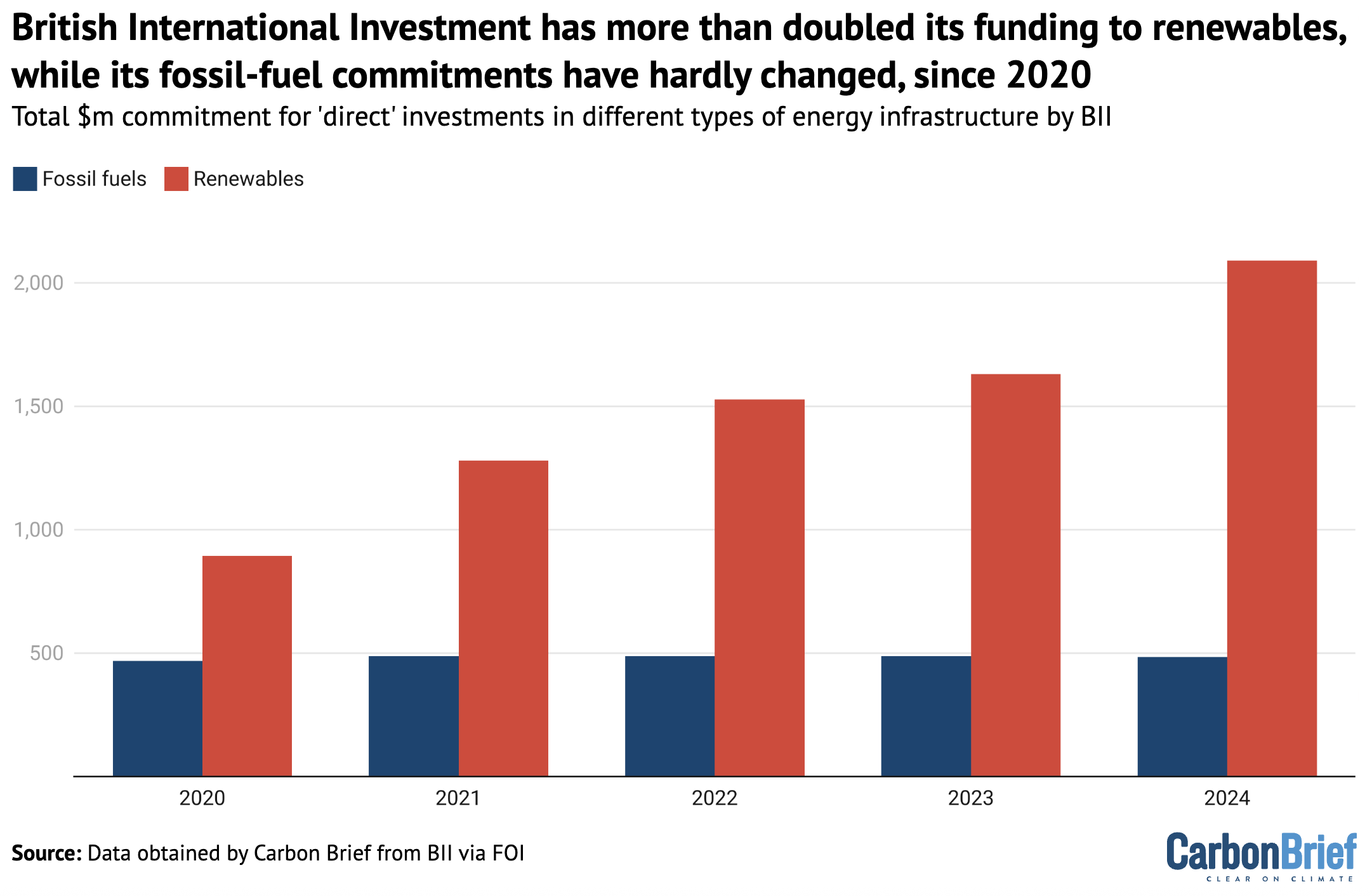

As the chart below shows, BII’s cumulative commitments to fossil-fuel companies have remained roughly the same since its climate strategy in 2020. This is in line with its pledge to provide no “new commitments” to most fossil-fuel projects.

One exception is an extra $20m (£15m) in 2021 for Globeleq, a company controlled by BII that primarily supports gas power in Africa. An investment in a Mozambique gas project that year by Globeleq was deemed “Paris-aligned” and, therefore, allowed under BII’s rules.

Meanwhile, BII’s total commitments to renewable energy projects have more than doubled, from $894m (£672m) to $2.1bn (£1.6bn), between 2020 and 2024.

Once funds have been “committed”, they can remain “undrawn” for many years. This means that money committed before 2020 can still be distributed without breaching BII’s pledge. Carbon Brief asked BII how much of these “commitments” remained undrawn each year.

This revealed that BII has continued sending money to fossil-fuel projects since its 2020 pledge, disbursing around $57m (£43m) over this period. At the end of 2024, there was still $67m (£50m) of “undrawn” fossil-fuel finance waiting to be spent.

BII tells Carbon Brief that, as “commitments” are legal contracts, it is obliged to provide these funds as and when they are required.

Beyond “direct” investments in energy projects, BII has also made “indirect” commitments to fossil fuels via private financial institutions. The company tells Carbon Brief it does not have details of how much these third-party funds invest in fossil-fuel projects.

Daniel Willis, finance campaign manager at the NGO Recourse, points to examples such as Gigajoule and Ademat, companies that have received new finance injections for fossil-fuel projects beyond the 2020 date, on BII’s behalf. (Again, this is allowed under BII’s guidelines.)

Willis tells Carbon Brief that these investments and the continued payments from existing commitments “clearly go against the spirit of the UK government’s fossil fuel policy”.

BII initially rejected Carbon Brief’s request for the “net asset value” of every fossil-fuel investment in its portfolio. It argued that disclosure could weaken its commercial position.

However, the company eventually agreed to disclose the aggregate value of its fossil-fuel assets for the period 2020-2023.

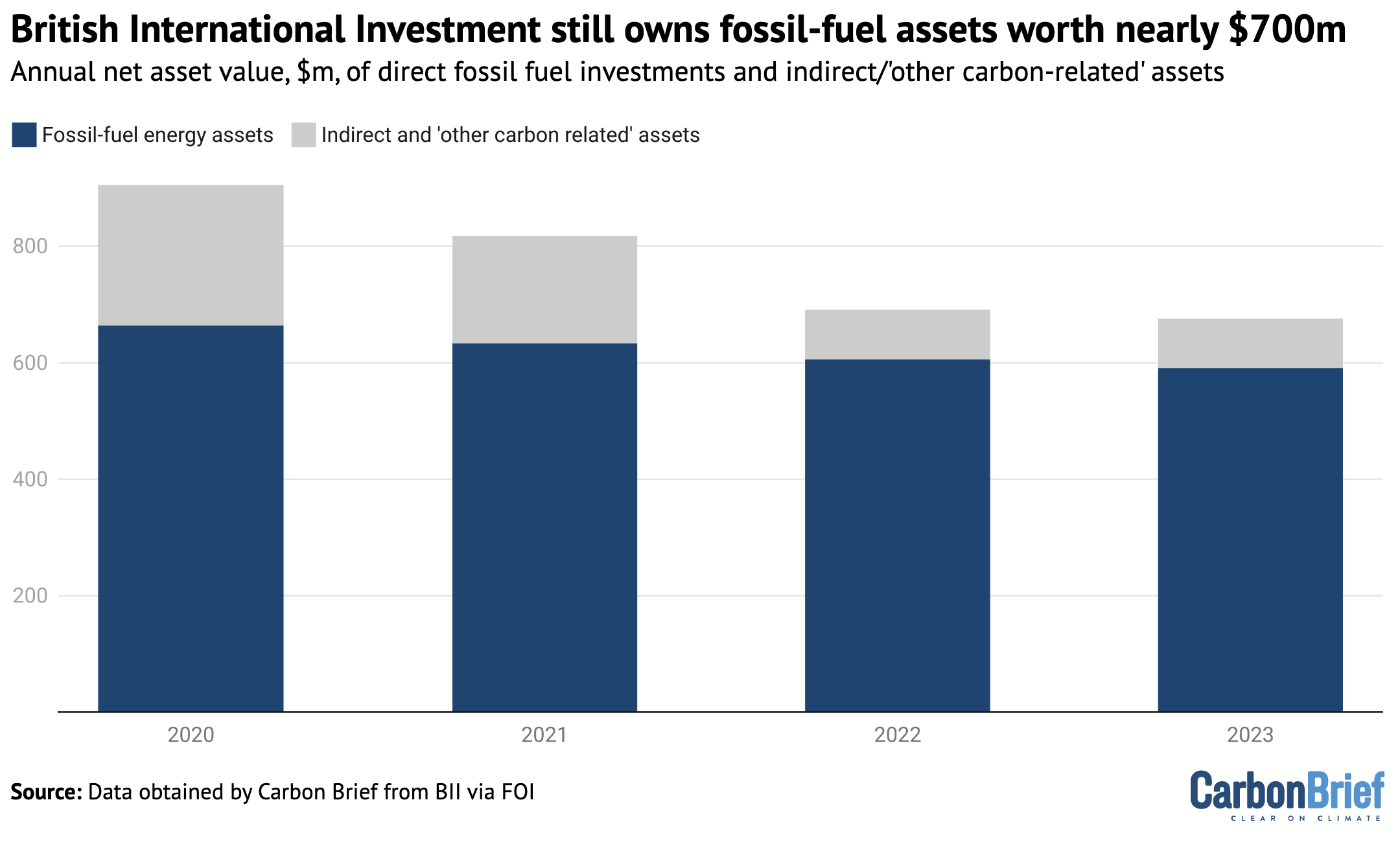

The data reveals that, as of 2023, BII still owned $591m (£444m) worth of gas-fired power plants and other fossil-fuel energy assets, rising to $676m (£508m) when indirect assets are included. This amounts to around 6% of BII’s assets.

While BII declined to provide Carbon Brief with the 2024 figures, a company spokesperson tells Carbon Brief that they plan to release them “this summer”, adding:

“Our 2024 annual report and accounts…will show that our exposure to fossil-fuels assets has fallen 39% since 2020 and now makes up just 6% of our total portfolio. Over the same period, the value of our climate-finance portfolio has increased by 122% to $2.5bn [£1.9bn] and now accounts for 26% of our total portfolio.”

As the chart below shows, there has already been a gradual drop in the value of BII’s direct fossil-fuel energy investments since 2020. The decline can likely be attributed to investees paying off debts to BII, fossil-fuel assets losing value and – to some extent – BII exiting smaller investments.

With evidence that BII’s fossil-fuel portfolio is declining in value, Sandra Martinsone, policy manager at the international development network Bond, tells Carbon Brief that “sooner or later” these will likely become stranded assets:

“The longer BII holds on to these fossil-fuel investments, the higher the risk of losing the invested aid pounds.”

The drop in the value of BII’s indirect fossil-fuel and “other carbon-related” assets – which includes non-energy companies that serve fossil-fuel companies – has been sharper. This can be largely attributed to BII ending support for fossil-fuel trade and supply chains in 2022.

‘Worrying trajectory’

In its FOI response, BII says that it “seeks to manage and responsibly exit fossil-fuel assets”. However, NGOs and politicians have raised concerns about the pace of change.

Natalie Jones, a policy advisor specialising in fossil-fuel phaseout at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), tells Carbon Brief that while BII has not breached its own climate guidelines:

“The fact that fossil fuel investments remain on BII’s books is not a good look for the organisation, bearing in mind its 2020 commitment to aligning its activities and investments with the Paris Agreement and the UK’s 2021 policy to end all international public support for fossil fuels.”

Civil-society groups have repeatedly called for BII to set a timeline for divesting from fossil fuels. They have even argued that, in the context of “drastic” UK aid cuts, BII should not receive more aid funding and instead reinvest funds from some of its existing assets.

Criticism of BII’s approach to fossil fuels is captured in a 2023 report by the International Development Committee of MPs. It refers to BII legacy investments “conflicting” with UK policies, including the alignment of all aid with the Paris Agreement.

The report also notes that there “does not appear to be a definitive path for BII exiting those fossil-fuel investments or transitioning its existing investment portfolio to green energy”.

Committee chair and Labour MP, Sarah Champion, says that, while the most recent data is not yet publicly available, the figures released to Carbon Brief point to a “worrying trajectory” in BII’s fossil-fuel investments. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It appears that BII has stayed on this worrying trajectory. This must change: as the government proposes a new strategic direction for UK aid spending, focusing on poverty reduction and genuinely responsible investment must be BII’s number one priority.”

In a statement alongside its FOI response, BII says that “forced divestment increases the likelihood that buyers of such assets would be less responsible owners, thereby increasing the future risk of negative climate impact”.

It also says that “being viewed as a forced seller” could reduce the value BII could obtain from those assets. This position was supported by the previous Conservative government.

Jones tells Carbon Brief that concerns about the responsibility of new owners are legitimate:

“However, it would be great to see from BII a plan to responsibly exit or, even better, decommission their fossil fuel assets. There is a case to be made for a responsible exit that would free up funds for much-needed climate finance.”

BII argues that, with around 600 million Africans still lacking access to electricity, gas power remains “essential” for providing “baseload” power to many nations on the continent.

This position has been supported by a number of African governments. However, many civil-society groups, both in Africa and around the world, argue that developed countries should focus financial resources on expanding clean power capacity in developing countries.

Nick Dearden, director of Global Justice Now, which has previously questioned the legality of the BII-controlled Globeleq supporting gas power in Africa, tells Carbon Brief it is “inappropriate” for aid money to be spent this way:

“It’s also trapping the countries that are building this stuff into a type of energy which is on its way out.”