Revealed: Use of heat ‘emergencies’ for rough sleepers hits record in England and Wales

Josh Gabbatiss

09.25.25Josh Gabbatiss

25.09.2025 | 8:00amA record number of heat-related “emergencies” have been triggered by councils this year to help rough sleepers in England and Wales, Carbon Brief analysis reveals.

As climate change drives more heat extremes, there is a growing recognition that homeless people face a higher risk of illness and even death when temperatures soar.

This summer has been the hottest on record in the UK, with official warnings about heat-related health threats issued across every part of England and Wales.

The main tool councils have to help people sleeping rough during dangerously hot periods is the “severe weather emergency protocol” (SWEP).

Freedom-of-information (FOI) requests submitted by Carbon Brief to 93 local authorities across England and Wales with significant rough-sleeper populations reveal that SWEP use has surged this year.

Many councils have used the protocol to provide water, sunscreen and “cool spaces” for rough sleepers.

However, at least 20 councils said they have never triggered a SWEP during the summer months and others failed to provide any information when asked.

Dangerous heat

Climate change is increasing the severity of dangerously hot weather in the UK and these conditions harm certain groups more than others.

People sleeping rough are both more exposed to heat due to their living conditions and more likely to experience heat-related illness, due to underlying health conditions and other issues.

Councils shoulder much of the responsibility for helping homeless people in England – the part of the UK that faces the most extreme heat – as well as in Wales.

The main mechanism councils have to deal with weather extremes is the SWEP, which can involve giving emergency shelter to rough sleepers, among other things. There is no legal obligation to use SWEPs, meaning their implementation is not consistent or universal.

SWEPs have traditionally been a response to cold weather, but there has been growing awareness in the UK of the risk posed by heat, particularly since the extreme temperatures of summer 2022.

Charities and researchers have highlighted this issue and argued for hot-weather use of SWEPs as a necessary precaution to protect rough sleepers during heatwaves. In 2023, the UK government issued its first guidance for helping homeless people during hot weather.

Record SWEP

To investigate how local authorities are helping rough sleepers deal with heat extremes, Carbon Brief sent FOI requests to 90 councils in England and three in Wales.

This covers all areas with a sizable rough-sleeper population (see: Methodology). It also includes 33 London boroughs, which together are home to a quarter of the homeless population in England and Wales, plus the Greater London Authority.

Carbon Brief asked whether councils had been using SWEPs, how often and on which dates, during the summer months from 2022 to 2025.

This period saw the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) announce around 40 “heat-health alerts” across different parts of England, indicating temperatures that threaten public health.

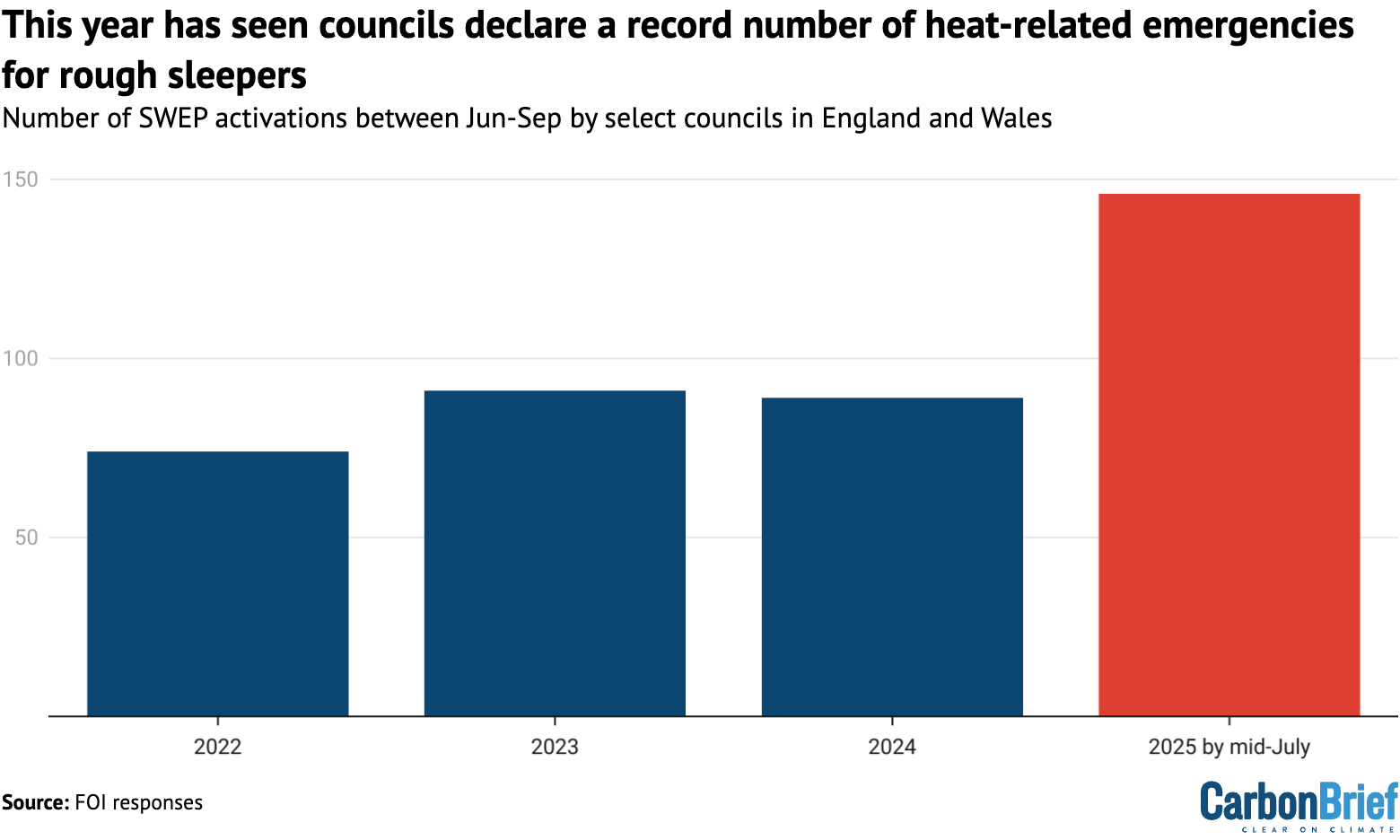

The council FOI results reveal a surge in SWEP usage in 2025, as the UK faced its hottest ever summer. Just half way through summer in mid-July, councils had already collectively triggered SWEPs at least 149 times – up from 93 in the entirety of summer in 2024, as the chart below shows.

Not all SWEP activations are the same, with some councils using it for single days and others triggering it for longer stretches.

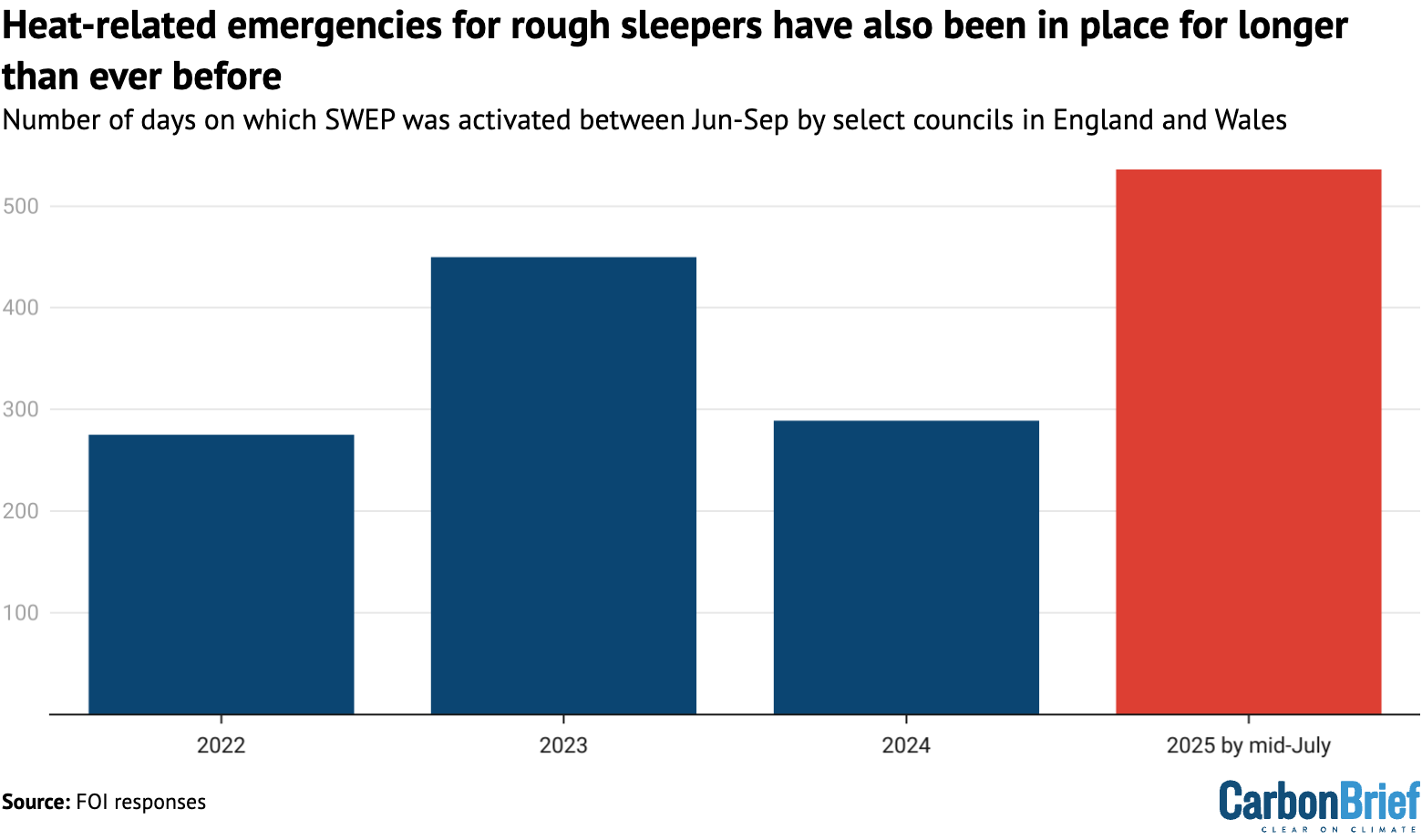

Nevertheless, roughly the same trend emerges when looking at the total number of days that councils have activated SWEPs since 2022. By mid-July, 2025 had already seen the longest period of SWEP activation, as the chart below shows.

The surge in SWEP activation mirrors both the record UK heat in 2025 and the growing salience of this issue, with more councils making use of it during the summer months. By July, 48 councils had triggered heat-related use of SWEPs this year, compared to just 36 two years earlier.

The increase may also reflect the numbers of people sleeping rough, which have surged in England over this time period, while remaining relatively steady in Wales.

‘Inadequate’ assistance

Previous analysis in 2023 by the Museum of Homelessness, a London-based organisation that researches homelessness, concluded that SWEPs were “inconsistently applied” and “inadequate”. It highlighted particular shortcomings in heat-related use of SWEPs.

Despite the surge in SWEP use this year, the data provided to Carbon Brief suggests that some councils are still not responding urgently to periods of extreme heat.

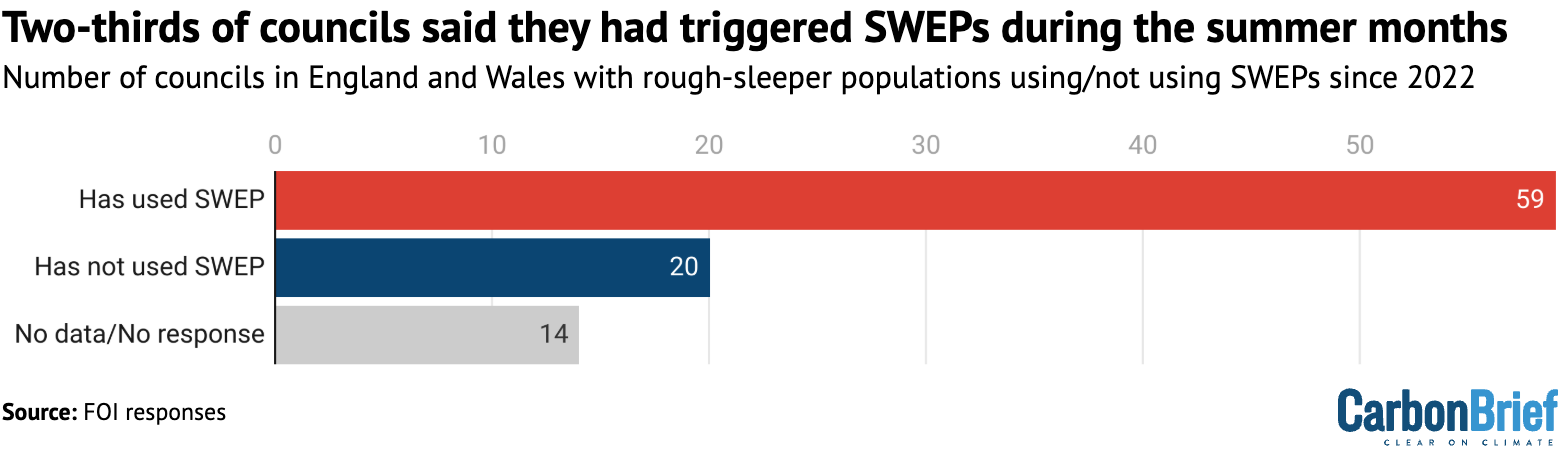

Of the 93 councils that Carbon Brief requested data from, 59 – or 63% – confirmed that they had activated SWEPs at least once during the summer months between 2022 and 2025, as shown in the figure below.

Common provisions resulting from this activation included the distribution of sunscreen, bottles of water and sun hats, as well as making “cool spaces” available and providing extra welfare checks. Most councils did not mention providing emergency accommodation.

Among the remainder, 14 councils either did not hold the data requested or never responded.

This leaves 20 councils that stated they did not trigger SWEPs at all during summers over this period, including those in Manchester, Nottingham and Cornwall.

All of the regions covered by these local authorities were issued with heat-health alerts in 2025.

Some of these councils said they were mindful of hot weather and mentioned other actions taken during these periods, some of which overlapped with SWEP responses.

Other councils, including Plymouth, Hastings and the London boroughs of Waltham Forest and Barking and Dagenham, did not mention any provisions for rough sleepers during periods of extreme heat.

Matthew Turtle, co-director of the Museum of Homelessness, tells Carbon Brief:

“These findings, like our own research, show that many councils opt not to help people who need it the most when there is extreme weather…This is not just smaller councils, but includes major towns and cities across the UK, who simply have no emergency protocol in place to protect people who are homeless during spells of extreme weather.”

Turtle argues that the use of SWEP should be made a legal duty in order to guarantee protection from extreme weather for those sleeping rough.

Researchers have argued that extreme heat should be taken more seriously by authorities when dealing with rough sleepers, with one study finding that homeless people in London were 35% more likely to be hospitalised at 25C compared to 6C. The authors suggest this is because people are better prepared for the threat of cold weather.

Dr Becky Ward, a researcher at the University of Southampton who is investigating how climate change interacts with homelessness, tells Carbon Brief that “the conversation is changing and awareness is building” about this issue. She adds:

“There’s a more fundamental need to improve the provision of shelter for people experiencing homelessness, alongside providing psychological support to address the causes and maintaining factors for people who are rough sleeping.”

Methodology

Carbon Brief obtained the list of 93 local authorities with significant rough-sleeping populations in England and Wales from the Museum of Homelessness. The criteria for this included being in one of the top 50 most populated cities in the UK, having a rough sleeping count of at least 15 people and/or being a London borough. These councils make up 28% of the 317 local authorities in England and 14% of those in Wales.

FOI requests were sent to these councils, asking for details of when SWEPs were activated and for how long over the summers of 2022-2025, as well as information about what activities this involved. (These requests were sent in mid-July, meaning data for 2025 is only for half the summer period.)

Carbon Brief asked for SWEP activations between June and September, mirroring the timescale used by the UKHSA and the Met Office for their heat-health alert service.

The results demonstrate the ad-hoc nature of SWEP use, with different councils using it in different ways and some relying on third-party organisations to coordinate their responses. Nevertheless, the combined results capture overall trends.

Some 20 councils said they did not record SWEP activations, or only kept partial records. Another five never responded to Carbon Brief’s FOI request.

In this article, Carbon Brief has used the term “rough sleeper” when referring to people sleeping outside or in other spaces not designed for people to stay. When referring to studies or datasets that cover the wider homeless population, the term “homeless” has been used.