Scientists are ‘most trusted’ source of climate information in global-south survey

Ayesha Tandon

08.22.25Ayesha Tandon

22.08.2025 | 10:00amScientists are the most trusted source of information for climate change in some of the largest global-south countries, ranking above newspapers, friends and social media.

This is according to a survey of 8,400 people across Chile, Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Vietnam, the results of which have been published in Nature Climate Change.

The study finds that trusting and paying attention to climate scientists was associated with increased climate knowledge, roughly twice the effect size associated with a college degree.

One scientist who was not involved in the research says the findings suggest there is an opportunity to “bolster climate knowledge” in the global south by widening access to climate science information.

When asked to rank how important climate change is for their country, participants rated the issue as high, with the average score for each country above 4.4.

However, when asked to rank the importance of climate change compared to other key social issues, respondents – on average – ranked taking action on climate change ninth out of 13, after improving healthcare, decreasing corruption and increasing employment.

Another expert not involved in the study says the results highlight a “crucial tension” between “strong” public concern about climate change and the perception that other social issues should take priority when allocating “scarce” public resources.

Global-south focus

The impacts of climate change are disproportionately felt by the poorest members of society, who often live in the global south.

Nevertheless, Dr Luis Sebastian Contreras Huerta – a researcher in experimental psychology at Chile’s Universidad Adolfo Ibanez – tells Carbon Brief that research on climate attitudes has been “heavily biased” toward the global north.

Voices from the global south are “often invisible in science”, he adds.

Huerta was not involved in the study, but has published research using surveys to assess public beliefs about climate change. He describes the new study – which is evenly distributed across Chile, Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Vietnam – as “a valuable attempt to capture public views across Latin America, Africa and Asia”.

The seven countries featured in the research include six of the 20 largest in the global south and range from “the lower end of low-to-middle-income countries (Nigeria) to the low end of high-income countries (Chile)”, according to the study.

The survey was administered online by polling company YouGov between April and May 2023. Respondents could answer in English or in other “country-specific languages”. For example, respondents in Chile and Colombia had the option to carry out the survey in Spanish, while those in India could answer in Hindi.

Trust and attention

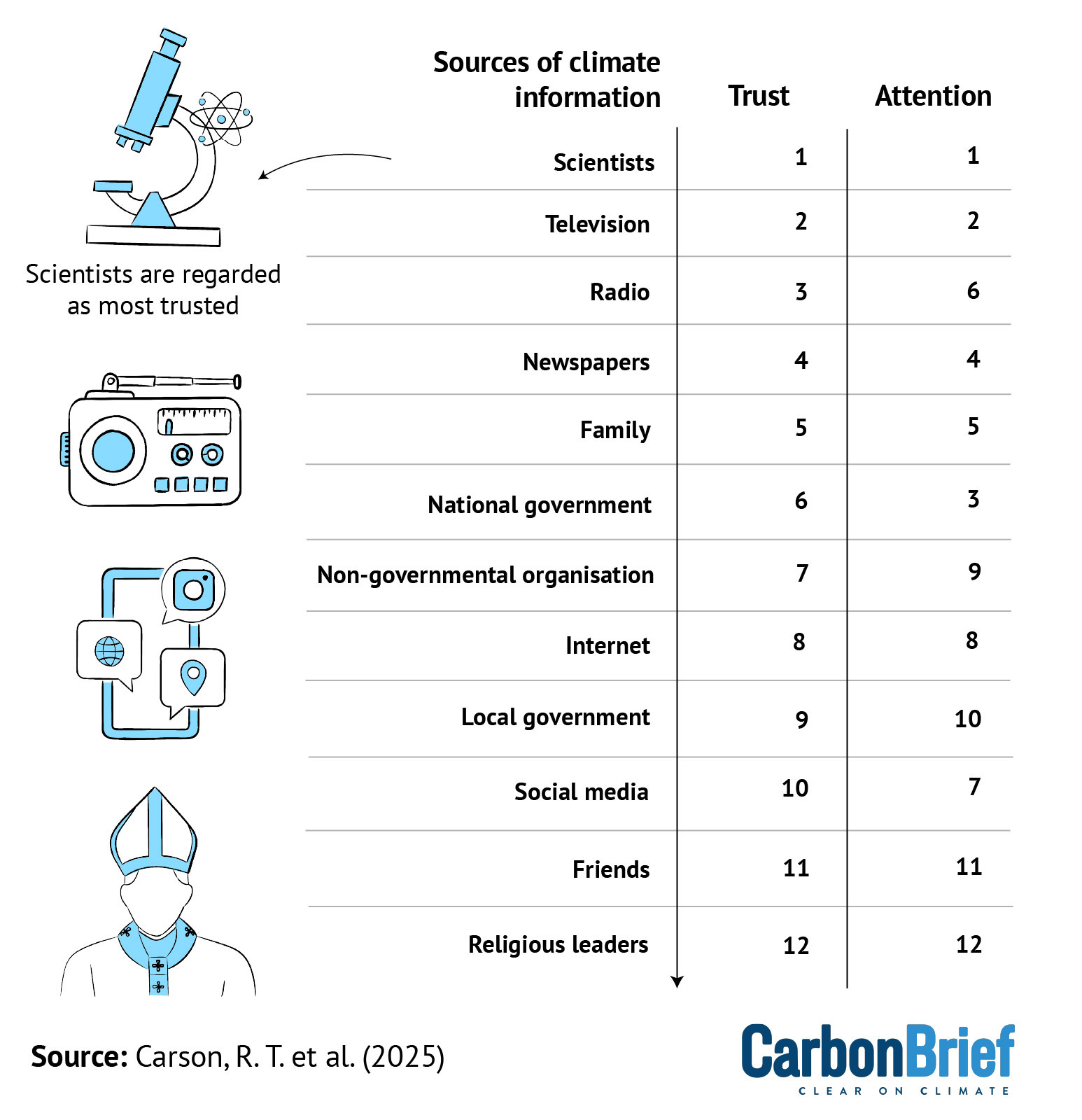

The authors asked survey respondents to rank 12 different sources of information about climate change, based on the attention they pay it and how much they trust it.

The average rankings are shown in the table below, where one indicates the highest level of attention or trust and 12 indicates the lowest.

The table shows that, on average, scientists are ranked the highest for both trust and attention.

The country-specific results show that scientists rank the highest in trust in every country except Vietnam, where they rank second highest after television programmes. Meanwhile, friends and religious leaders rank the lowest for trust.

Huerta says it is “encouraging” that the general public “tend to trust scientists as their main source of information”.

However, he warns Carbon Brief about “social desirability” – a phenomenon in which people respond to surveys in a way that they think will be viewed favourably by others. In this case, it means that “people may report higher trust in scientists and less reliance on social media than they actually practice”, Huerta explains.

Dr Charles Ogunbode is an assistant professor in applied psychology at the University of Nottingham. He is not involved in the paper, but has carried out research on public perceptions of climate change.

He tells Carbon Brief that the relatively low attention and trust shown to family and friends is a “remarkable finding that stands in contrast with conventional knowledge”. He continues:

“Previous psychological research on this topic (generally predominated by western samples) would support an expectation that people would have greater trust in interpersonal social referrents like friends and family…

“I think the findings from the study signal an opportunity to bolster climate knowledge in the global south by widening access to scientific information on climate change.”

Climate knowledge

The survey also assesses the level of climate knowledge of the respondents, by asking them to identify whether a series of statements are true, false, or if they are “not sure”.

More than 80% of respondents correctly identified that the following two statements are correct:

- Climate change is mainly caused by human activities.

- Warming leads to more extreme events, such as droughts, floods and storms.

Conversely, fewer than 20% of people correctly identified the following two statements as false:

- Nuclear power plants emit CO2 during operations.

- Today’s global CO2 concentration has occurred in the past 650,000 years.

Knowledge about climate change was “quite similar” across countries, according to the survey. However, the authors found that women are more likely to respond “not sure” than men.

The study finds that trusting and paying attention to climate scientists was associated with increased climate knowledge, roughly twice the effect size associated with a college degree.

Policy comparison

Early in the survey, respondents were asked to rank how important climate change is for their country on a scale from one to five. On average, all countries ranked climate change above 4.4 on this scale.

However, the survey later asked respondents to rank the 13 government programmes, including climate, healthcare and education, in order of importance.

The authors found that “addressing climate change” ranks at ninth, on average, across the seven countries.

Climate change ranks the highest in Vietnam, where it comes in second behind “decreasing political corruption”.

However, it ranks 10th in Nigeria and South Africa, beating only “improving public transport”, “improving access to credit” and “getting Covid-19 under control”.

Lead author Prof Richard Carson, a professor of economics at the University of California, tells Carbon Brief that asking respondents to rank different issues “provides a much richer picture of the structure of public opinion on climate issues” than asking them to rank issues separately. This, he says, is because it forces respondents to make “direct tradeoffs”.

The survey shows that “people might say that dealing with climate change matters – but this does not mean that they would place it on the leaderboard when it comes to priorities”, he adds.

Huerta – the experimental psychology researcher – tells Carbon Brief that results highlight “a crucial tension”. He explains:

“Athough people show strong concern for climate change, when it comes to allocating scarce public resources, priorities such as health, education, poverty reduction, and security often come first.”

He adds:

“People may genuinely care, but without clear, immediate benefits, climate action is often deprioritised – unlike issues such as air pollution, where the consequences and gains are more tangible.”

The authors also asked survey respondents to rank seven “health-related issues”, with respiratory problems consistently identified as the highest priority.

Huerta says the results show a “disconnection”, adding:

“People rank respiratory illness as a top health concern, but they do not always connect it with climate change more broadly. This highlights a key communication challenge for climate policy.”

Finally, the authors asked respondents to rank their preference for the use of a carbon tax. In keeping with the results above, “spend on education and health” ranks top of the list. This is followed by subsidising solar panels and investing in “clean research and development”.

Dr Stella Nyambura Mbau is a lecturer at Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that “the preference for earmarking carbon tax revenue for health, education and renewable energy subsidies aligns with community-based adaptation strategies, such as solar-powered solutions, that address immediate needs while building resilience”.

She suggests that prioritising policies that can tackle climate change alongside other social issues could “bridge the gap between climate action and local priorities”.

Next steps

The authors note that their survey could only be completed by people with access to the internet, meaning that it “systematically underrepresents those with lower income, living in rural areas and who are older”.

Only people over the age of 18 were allowed to complete the survey. Across the countries, the median age of respondents was 31 years old. There was also a slight skew towards men, who made up 55% of the respondents.

As such, some external experts pointed out that results could be skewed.

For example, Prof Tarun Khanna, an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, notes that when ranking uses for carbon taxes, there was low support for policies such as returning money to the poor. He questions whether this could be “because the survey concentrates on a relatively affluent class of people”.

Dr Nick Simpson is chief research officer at the University of Cape Town‘s African Climate and Development Initiative Climate Risk Lab and has led separate research on general public perceptions of climate change in Africa.

He praises the study’s “large, cross-national dataset” and “rigorous statistical techniques”. However, he adds:

“The survey questions focus primarily on mitigation [greenhouse gas emissions prevention and reduction] responsibilities, reflecting a global north bias in climate surveys. [The questions] do not fully capture urgent adaptation concerns or the lived realities of climate vulnerability in low and middle-income countries.”

Future research should incorporate more “adaptation-specific questions” in order to “provide a more holistic understanding of climate action priorities”, he says.

Carson, R. T. et al. (2025) The public’s views on climate policies in seven large global south countries, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-025-02389-9