Sweltering in the city: Surviving climate change in our great urban metropolises

Roz Pidcock

04.30.14Roz Pidcock

30.04.2014 | 11:00amThis is the age of the megacity: urban areas with populations of more than 10 million are on the rise. And as more and more people flock to the city, rising temperatures and heatwaves are likely to make life difficult in urban centres, scientists say.

Some highlights from this week’s European Geosciences Union (EGU) conference explain why cities are so vulnerable – and offer suggestions for how citizens can ease the pressure.

Population explosion

By 2050, the global population is expected to grow to 9.6 billion, up from one billion at the start of the Industrial Revolution. Of the growing population, 75 per cent are expected to live in cities.

Rapid population growth and urbanisation are having profound impacts on our environment. As John Burrows, professor of atmospheric physics and chemistry at the University of Bremen, told journalists at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) conference this morning:

“Humans are no longer a passenger on this planet, we’re driving it.”

As more people are moving into cities, urban areas becoming more crowded, and at the same time they’re expanding outwards.

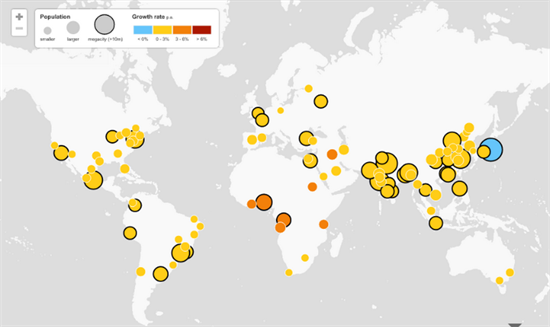

As this Guardian interactive explains, 23 cities are currently classed as megacities, including New York, Sao Paulo, Dakar and Tokyo. That means they have a population of more than 10 million.

And that number is growing. By 2025, the United Nations predicts there will be 37 in total.

United Nations research suggests there will be 37 megacities by 2025. Source: Guardian Interactive.

Urban heat islands

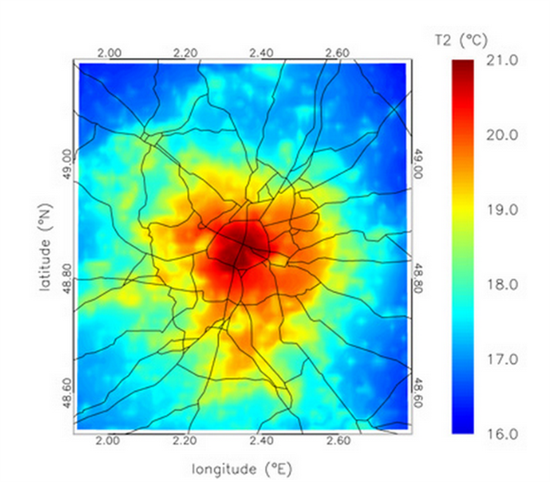

People, buildings and industry are densely packed in cities. Heat gets trapped, meaning the ambient temperature is often higher than the immediate surroundings. This is known as the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, and scientists expect it to intensify as the climate warms further.

Not all towns and cities are the same. Research by Bin Zhou from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research finds the summer UHI effect is closely related to the size of the city. But other factors such as the layout, how much vegetation exists and the proximity of the city to the sea (where breezes have a cooling effect) all affect how big the UHI is, other research suggests.

Paris during the European heat wave in summer 2003, when temperatures in the city centre were several degrees higher than outside the city. Source: VITO, Planetek

Hot extremes

We’re already seeing more frequent and more intense high temperature extremes and heatwaves in many parts of the world. And climate change is expected to bring more of the same, says the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The body’s recent report concludes:

“It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia [â?¦]. It is virtually certain that there will be more frequent hot and fewer cold temperature extremes over most land areas on daily and seasonal timescales as global mean temperatures increase. It is very likely that heat waves will occur with a higher frequency and duration.”

Cities are particularly vulnerable to many climate change impacts, a follow-up to the IPCC report concluded last month. But relatively few studies exist on how temperature extremes affect cities, explained Professor Dennis Lettenmeier in his talk at the EGU conference this morning.

Lettenmeier’s research shows urban centres have experienced a significant increase in heatwaves during the period 1973 to 2012, and a decline in the frequency of cold waves. Of 217 cities studied, almost half saw a rise in the number of hot days and two thirds experienced more hot nights.

There’s little research on what life in cities will be like years from now. Yet, models that realistically represent urban areas and how they might respond to warming are critical, said Dan Li who is working on one such model at Princeton University in the United States.

Mapping heat stress

Another presentation looked at what cities can do to keep temperatures down and make life more bearable for their inhabitants.

Catherine Stevens, an expert in geographic information management from Belgium, introduced a new EU project called NACLIM looking particularly at the European cities of Antwerp, Berlin and Almada.

It aims to produce maps of potential heat stress by downscaling projections from global climate models to the regional scale and combining the data with information on populations’ exposure and vulnerability.

Planners and decisionmakers can use the maps to build more resilient cities by targeting the introduction of “green roofs”, for example, say the researchers.

Talking to residents about what they can do to lessen the impact is an important part of the project’s aims, Stevens said. And according to other research presented, people’s individual efforts to adapt their behaviour to higher temperatures makes a big difference.

Softening the blow

A survey of 428 people by Tina Kunz-Plapp from the Institute of Technology in Germany found the ones who rated themselves the least heat-stressed following a prolonged hot period in summer 2013 were those who were able to adapt their daily activities – by drinking more water, for example.

On average, respondents aged 65 years and older reported lower heat stress levels that younger ones, due to more flexible routines, the researchers suggest.

Reducing heat stress isn’t just important for keeping healthy, says Kunz-Plapp – it could also reduce impacts on work performance and productivity.

Gaining momentum

It’s not just rising temperatures that cities need to contend with. There are added risks from extreme rainfall, flooding, air pollution, drought and rising sea levels.

For some coastal megacities like Jakarta and Bangkok, there’s yet another problem – the land is sinking as a result of too much groundwater extraction, something researchers at EGU are warning could be an even bigger problem than sea level rise.

How cities will be affected by climate change – and what growing populations can do to alleviate some of the pressure – is a new area of research, but is rapidly gaining momentum.

Main image: Sunset over Dubai city. Credit: Anna Omelchenko/Shutterstock.com.

-

Sweltering in the city: Surviving climate change in our great urban metropolises