Mat Hope

07.01.2014 | 12:30pm2014 started with some seemingly good news: Independent media aggregators, The Daily Climate, said its analysis showed climate change reporting had “leapt” in the previous 12 months. Working out whether climate coverage is on the up is a rather complicated task, however.

The Daily Climate’s result may have come as something of a surprise to a group of US academics who had also been tracking climate change reporting. Max Boykoff, Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado, who has been looking at global climate coverage since 2004, found it dropped in 2013. Likewise, Drexel University sociology professor, Robert Brulle, found US television coverage of climate change was at almost exactly the same level in 2013 as it was in 2012.

This led the Columbia Journalism Review to conclude that the Daily Climate’s analysis had identified a “pseudo boom” in climate coverage, rather than a significant change of direction.

Perhaps more significant than The Daily Climate’s headline result is what the analysis tells us about the potential pitfalls of analysing media coverage of climate change. It shows that such work can can be cut many ways depending on what is being looked at, how the sample is collected, and how results are reported.

30 per cent? The Daily Climate and energy-climate reporting crossover

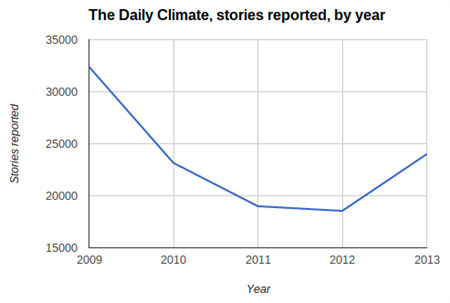

Each year, The Daily Climate reports how many climate change stories its researchers and computers find in publications around the globe. Its headline in 2013 reported a 30 per cent jump in climate change stories compared to 2012’s levels – the first time the number of stories had increased since 2009, as the graph below shows:

Source: The Daily Climate analysis, graph by Carbon Brief

The Daily Climate said the result “marks the end of a three-year slide in climate change coverage and is the first increase in worldwide reporting on the topic since 2009”. It said the 2013 jump was “fueled by reporting on energy issues – fracking, pipelines, oilsands – and a heavy dose of wacky weather worldwide”.

So why did the other trackers not see this jump?

One explanation for The Daily Climate’s result differing from others’ work is related to how it collated its sources. The Daily Climate is quick to acknowledge that other databases “count a story only if the words ‘global warming’ or ‘climate change’ appear”, unlike its own. So a story about fracking would get picked up in The Daily Climate analysis even if it didn’t talk about the implications for climate change, for instance.

That means The Daily Climate has a distinct view “about what is a climate change story and what is not”, Brulle tells the Columbia Journalism Review – and explains why it sees a jump where others don’t.

Moreover, The Daily Climate’s top line raises interesting questions about how the issues of climate change and energy relate to each other.

The Daily Climate’s editor, Douglas Fischer, tells the Columbia Journalism Review that energy stories are increasingly “connecting some dots” between economic choices and climate change impacts. As such, he argues that the definition of what constitutes a ‘climate change’ story can be legitimately extended to include those articles.

Boykoff’s drop

The Daily Climate’s method means it includes some stories which are only loosely connected to climate change, however. According to Brulle’s follow-up research, sometimes the stories included in The Daily Climate’s analysis don’t mention climate change or global warming, even implicitly.

As such, The Daily Climate is arguably taking too broad a view of what counts as a ‘climate change’ story. Max Boykoff and the Columbia University team take an alternative approach, with notably different results.

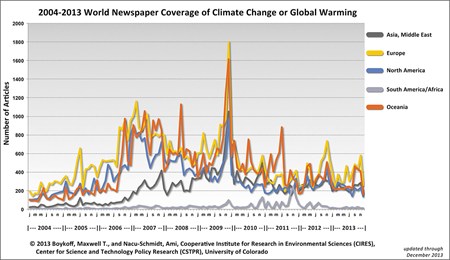

They use a number of search engines to look for the terms “climate change” or “global warming” across 51 newspapers worldwide (more detail on their method is available here). As this graph shows, they found a general drop in climate coverage in 2013:

Source: Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado

While this approach means only stories which explicitly mention climate change are included, it’s not without faults.

For instance, by only searching for those terms, the database could exclude stories which are about climate change, without ever actually using those words (perhaps talking about ‘greenhouse gases’, for instance). On the flip side, the database could also include stories which are only tangentially about climate change – with someone mentioning it in relation to another issue such as security or agricultural policy, for example. There are also potential difficulties when deciding which media outlets to include (“influential” ones, in this case).

Moreover, there remain questions over how the quantity of stories relates to the quality of the journalism, as Boykoff acknowledges in his 2011 book ‘Who Speaks for the Climate?’ For instance, how useful is it to include all climate change reporting under the same umbrella when some stories could be explaining new research, while others question existing evidence?

Those are questions which this sort of analysis alone can’t answer.

Looking more closely

One way to get around this is to focus on a particular issue, at a particular time, in a particular place, rather than looking at the broad sweep of climate change coverage.

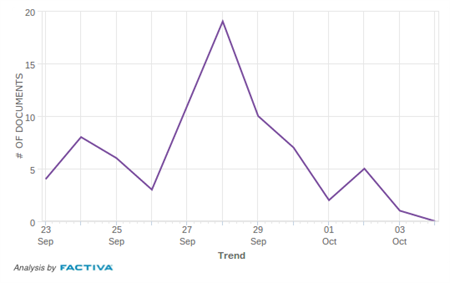

For example, we looked at the number of printed stories about the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s big report last October.

In total, there were 53 stories in the papers we looked at – the Daily Mail, Mail on Sunday, The Times, Sunday Times, The Telegraph, Sunday Telegraph, Guardian, Observer, and Independent. The coverage peaked with 19 stories on September 28th, the day after the report was launched. By the following Friday, coverage had all but tailed-off.

This more focused analysis tells us something about mainstream newspapers’ attention spans for that particular climate change story, and we can be confident that the lion’s share of those stories are relevant to the debate.

But it doesn’t say much about broader climate change reporting trends, as the other analyses attempt to.

An imperfect science

Analysing media reporting is tough, and none of these analyses are perfect. Nonetheless, all of them offer some insight into how climate change is reported.

Ultimately, they collectively serve as a cautionary tale: the headline results are only as strong as the databases they are drawn from, and the devil is normally in that particular detail.