Third of ‘slum residents’ in global south are exposed to ‘disastrous’ flood risks

Svetlana Onye

07.24.25Svetlana Onye

24.07.2025 | 12:38pmOne in three people in informal settlements in the global south live in floodplains and are at risk of a “disastrous flood”.

That is according to a new study published in Nature Cities, which measures the flood risk of global-south populations living in “slums” – as defined by UN-Habitat.

Using a combination of machine learning, satellite images, household surveys and socioeconomic data, the study finds that these slum populations are often concentrated in regions that have recently or frequently experienced severe floods.

Though large slum communities are vulnerable to floods, limited locational choices often mean that inhabitants have nowhere else to go, according to the study.

The research reveals the consequences of socioeconomic challenges when compounded with environmental pressures driven by urbanisation.

Dr Gode Bola, a water risk and climate scientist at the Congo Basin Water Resources Research Centre, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“Slums in the Congo Basin used to face flooding to an extent that communities could deal with. Rainfall, which is where climate change is coming in, has meant people are facing larger floods and it’s difficult for people to adapt.”

Hotspots and vulnerability

According to the UN definition used by the study, slum households are those in urban areas that lack at least one of the following: “durable housing, sufficient living space, easy access to safe water, adequate sanitation and security of tenure.”

Using this, the study estimates that at least 17% of the global-south population, equivalent to more than 880 million people, live in slums. For some countries, such as Sierra Leone and Liberia, a majority of the population live in slums, the authors note.

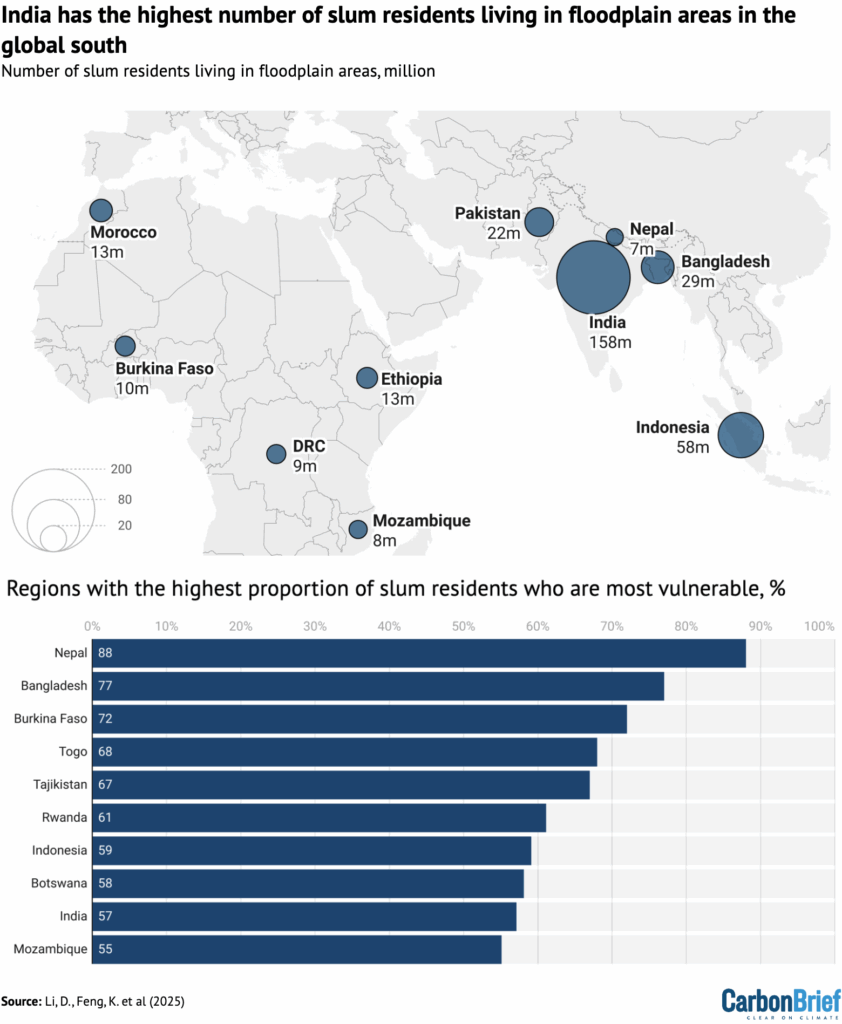

Many of these slum communities are situated in areas that face substantial flood exposure. The study identifies northern India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Rwanda and the coastal regions of Rio de Janeiro as notable hotspots – as the map below illustrates:

Beyond physical exposure, these communities face social vulnerabilities that are exacerbated by flooding. Poor infrastructure, limited access to social services and a lack of institutional support impede effective responses to floods in these areas, the study finds.

At 80%, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of slum populations living in floodplains, the study finds.

Despite these challenges, relocation opportunities for people living in slums are slim. Financial constraints and reduced access to employment make it difficult to move to safer areas. Flood zones often offer cheaper land or housing, which pushes poorer households into vulnerable areas, the study finds.

For example, flood-prone areas in Mumbai in India, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and Jakarta in Indonesia are considered “low value”, the authors say, making it more accessible to those in urban areas with lower incomes.

Nevertheless, the need for housing and an income continue to draw people to these flood-risk zones, separate research suggests.

Bola tells Carbon Brief:

“These slums are less expensive and poor people can afford the land. They buy this plot of land for life and asking them to relocate is asking them to have savings to buy another plot when there are no loans or government assistance.”

Disastrous floods

The authors mapped where slum populations are concentrated and where disastrous floods have historically occurred across 129 countries in the global south.

Disastrous floods were categorised in the study as events that resulted in “severe societal disruption, often leading to fatalities and severe humanitarian consequences”.

Their findings showed that, across the global south, those living in slums make up 35% of the total population, but account for 41% of those who live in flood-prone areas. This suggests that slum residents are more likely to settle in flood-risk areas in comparison to non-slum residents.

In fact, the study finds that in countries which often face disastrous floods, such as Bangladesh, slum residents are overrepresented in nearly all areas where disastrous floods have occurred.

Rourkela and Kinshasa’s slums

Floods in Rourkela, India, and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, in recent months illustrate the issue of slums being situated in floodplains.

Heavy monsoon downpours caused floods in slum settlements in Rourkela, while floods and landslides devastated 13 communes in Kinshasa’s urban slums, resulting in 165 deaths.

In Kinshasa, rapid urban growth is pushing development into floodplains without proper infrastructure, making floods worse and recovery harder, according to a recent article by researchers. As a result, healthcare systems and transportation are routinely damaged.

In India, separate research suggests that slum settlements are prone to flooding because many are in low-lying areas on the periphery of water bodies, without proper storm-water drainage.

According to the new study, rapid urbanisation and land pressures will likely drive even more slum populations into flood zones in the global south, indicating that the cases of Rourkela and Kinshasa could become an even more frequent reality.

Flood protection

The “intensifying” effects of climate change amplifies the need to address the location of slums in the global south, the authors state.

However, other research has shown that minimal policies to support slum communities in flood zones exist. Yet, as rapid urbanisation occurs, slums continue to spread into high-risk areas.

Poor governance has failed to recognise the rights and needs of the urban poor in city planning, according to research from Cities Alliance.

The study in Nature Cities mentions that governments are often politically reluctant to formally recognise slums because doing so could increase pressure to deliver services, complicate future development plans or damage the international image of the city or country.

Dr Nausheen Anwar, director of Karachi Urban Lab and principal researcher and urban climate resilience lead at the International Institute for Environment and Development, tells Carbon Brief about the government response to flooding of informal settlements in Karachi in 2022.

Anwar, who was not involved in the new study, says:

“People were living alongside the banks of those specific channels and were quickly labelled as encroachers, even though many of them had tenure in these informal settlements and the supreme court essentially backed the entire plan for eviction. This is where the role of the law became very effective in displacing people and razing their homes.”

The authors of the study say their findings can be used to inform data-driven policies that address flood risk, as well as to help shape local regulations.

In the study, they call for governments to recognise the inequalities that slum populations face and to acknowledge slum communities as key stakeholders. This would mean considering their needs and interests when designing policies to respond to climate change.

The authors also suggest that communities be empowered through capacity building, including training in sanitation and waste management.

Anwar adds:

“Data speaks for itself whether it comes in the form of numbers or is quantitative or qualitative…We need that to buttress the sort of changes we want to make on ground in terms of influencing policy agendas and planning interventions, whether it is at the local scale or going up even at the global scale.”

Li, D. et al. (2025) Disproportionate flood exposure for slum populations of the global south, Nature Cities, doi:10.1038/s44284-025-00273-3