Analysis: UK climate aid to hit £11.6bn goal – but only due to accounting rule change

Josh Gabbatiss

06.30.25Josh Gabbatiss

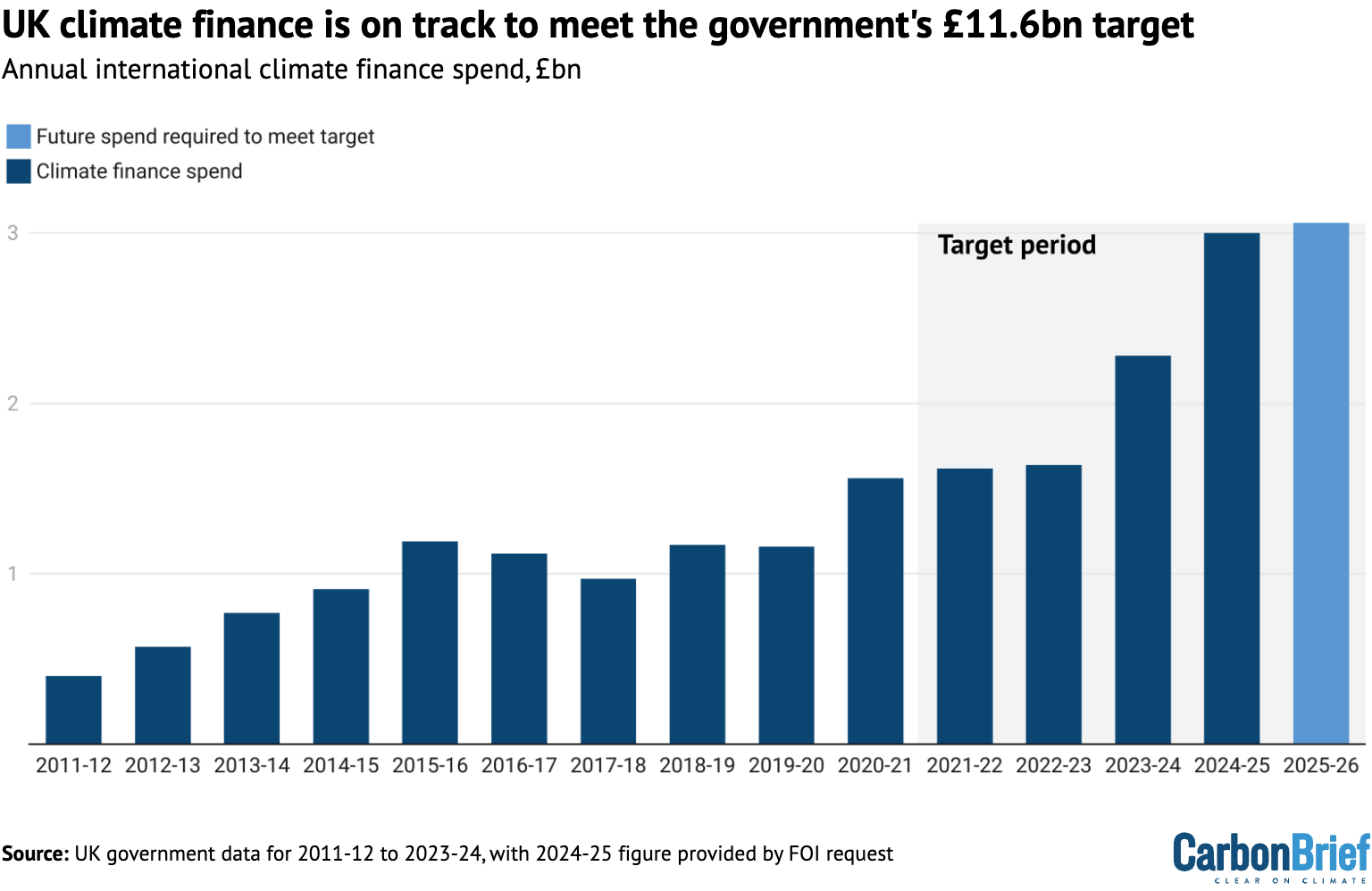

30.06.2025 | 12:01amThe amount of foreign aid the UK spends on climate action reached a record high of around £3bn last year, according to government figures obtained by Carbon Brief.

However, Carbon Brief analysis shows that more than £500m of this sum comes from controversial changes in the way the UK calculates its climate aid for developing countries.

By leaning on private-sector investment and including existing aid projects in the total, the government is able to inflate its figures without providing as much new climate funding.

Including this money puts the UK on track for its five-year goal of providing £11.6bn by 2026 to support climate action in developing countries, even as it cuts the overall aid budget.

Climate aid – which is often referred to as “international climate finance” (ICF) – will likely still need to rise above £3bn in 2025, if the UK is to achieve its target over the next year.

The new data, released to Carbon Brief via freedom-of-information (FOI) requests, covers provisional 2024-25 spending across the three major government departments that fund climate projects overseas.

This analysis is the latest in a series of articles by Carbon Brief documenting the UK’s ICF contributions since 2011.

Key findings from the most recent year include:

- By far the largest payment last year was a £482.3m contribution to boost British International Investment’s (BII) private-sector interests in developing countries.

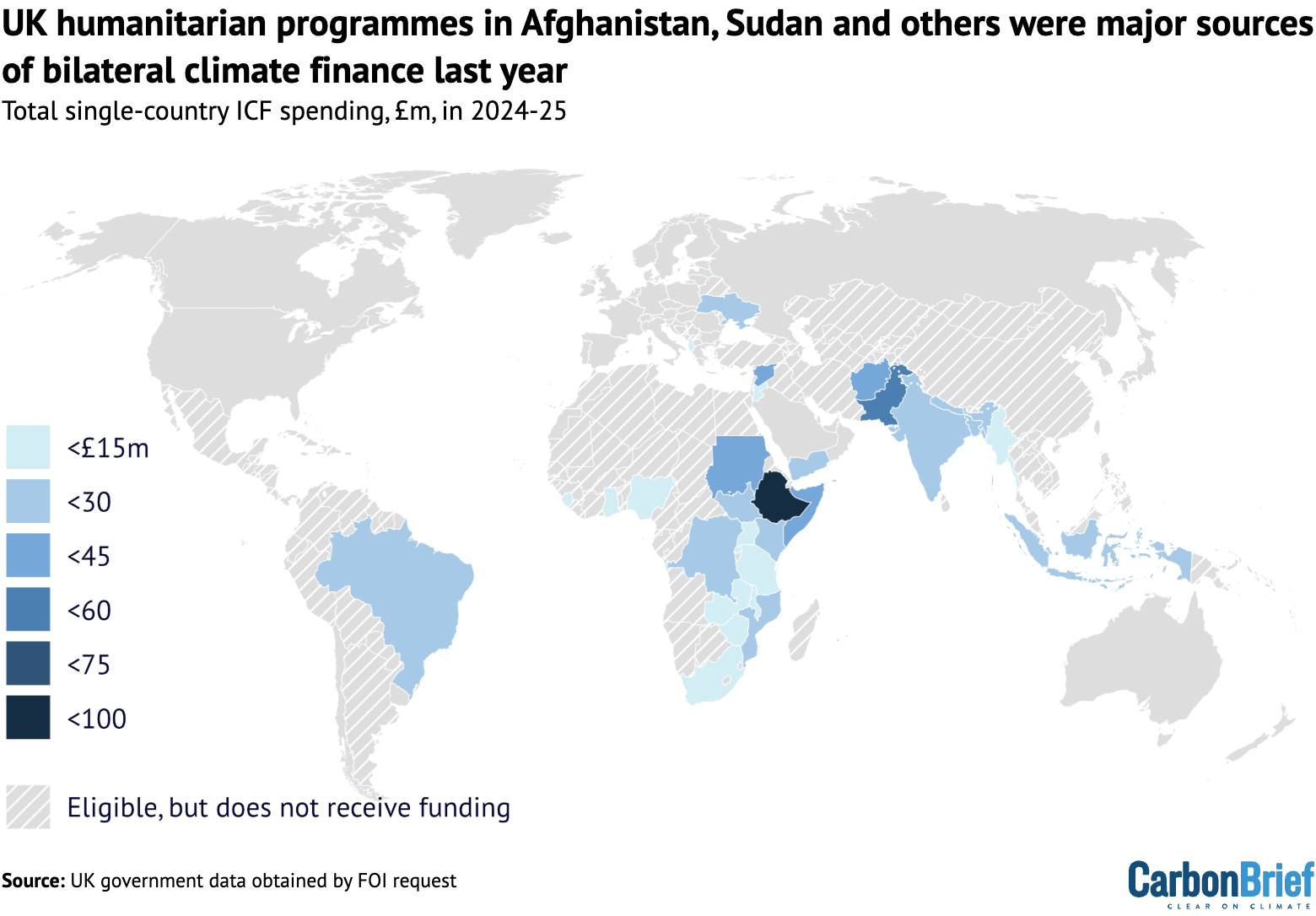

- Ethiopia was the largest recipient of bilateral climate finance (£92.3m). Other major recipients include Pakistan (£55.8m), Afghanistan (£43.7m) and Sudan (£41.1m).

- The biggest single project to receive funding was a World Bank initiative helping developing countries to sell carbon offsets, which received £153.9m.

- Large portions of climate finance also went to the Green Climate Fund (£227m) and the Global Environment Facility (£64.8m).

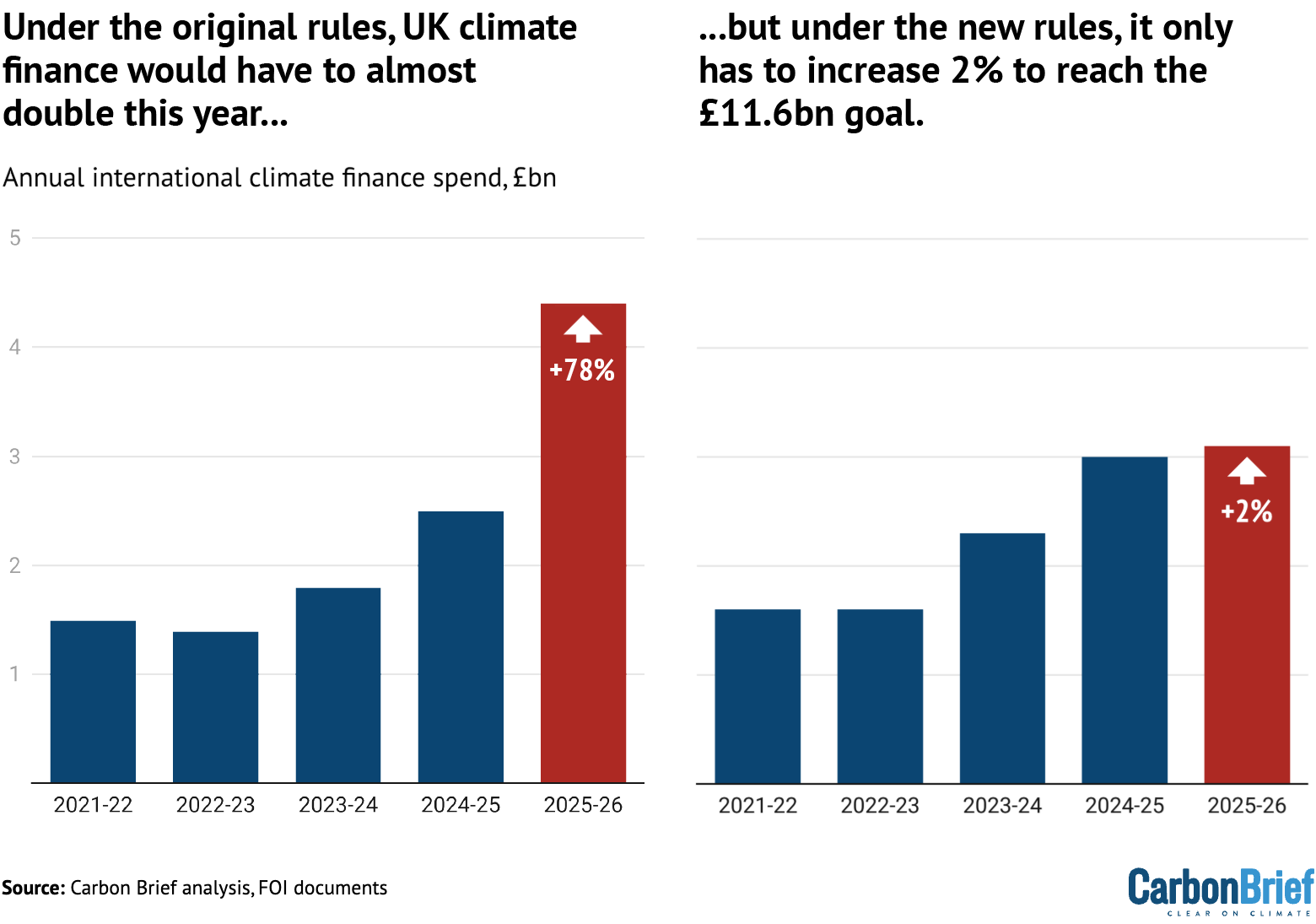

- Without the government’s changes, which mimic the looser accounting used by some other countries, climate finance would have needed to increase 78% this year. With the changes, climate finance only has to increase by 2%.

- Around £1.3bn – nearly a sixth of the UK’s ICF over the past four years – can be linked to the government’s accounting changes.

Target achieved?

After it was elected last year, Labour confirmed that it would honour the previous government’s pledge to provide £11.6bn of climate finance over the five-year period ending in 2025-26.

This money is the UK’s contribution, under the Paris Agreement, to help developing countries cut emissions and protect themselves from the threat of climate change.

Since the goal was first announced in 2019, experts have regularly voiced doubts that it can be achieved due to major cuts to the foreign-aid budget by successive governments.

More uncertainty followed the announcement in February that the Labour government would cut aid further – from 0.5% of gross national income to 0.3% – ostensibly to fund defence spending. (The government insisted that the remaining aid would “prioritise” climate.)

Despite these changes and uncertainty, the figures provided to Carbon Brief via FOI reveal that the UK is, in fact, on track to meet its £11.6bn target.

Climate-finance spending reached a record high of just under £3bn in the financial year 2024-25, more than £700m higher than the previous year.

(Note that these figures are “provisional” and subject to revision. Due to methodology changes, the final figures for UK climate finance in 2023-24 were much higher than those provided to Carbon Brief via a previous FOI. See the Methodology for more details.)

Assuming the provisional figures for 2024-25 are accurate, the UK would still need to raise its climate finance to £3.1bn in 2025-26 in order to meet the £11.6bn target, as shown in the figure below.

This level of climate finance would need to be maintained, even as the government scales back its overall aid budget in 2025.

When asked at a recent committee hearing whether there would be any new money for the £11.6bn goal, international development minister Baroness Chapman spoke frankly:

“I think the search for new money at the moment is going to be pretty fruitless…Is there going to be any new money for climate in a world where we have just gone from 0.5% to 0.3%? I think you can probably work that out.”

Instead of new funding, the upward trajectory of climate aid has been largely driven by the UK expanding what it counts towards the total. These changes were initially made under the Conservatives, but Labour has retained them.

By relabelling existing funding for multilateral development banks (MDBs), humanitarian aid and private-sector investments via BII as “climate finance”, the UK has inflated the figures without allocating genuinely new funds, making the £11.6bn goal easier to achieve.

Based on data acquired through successive FOIs, Carbon Brief estimates that £528m, or 18% of climate finance provided in 2024-25, can be linked to these accounting changes.

Since 2021, the running total of climate finance resulting from these changes is more than £1.3bn, Carbon Brief analysis suggests, amounting to nearly a sixth of spending to date.

Experts have pointed out that this amounts to a real-world cut in climate aid, as it means less additional funding than was originally pledged.

Without the accounting changes, UK climate finance would only have reached around £2.5bn last year, as the chart below shows.

To achieve the £11.6bn goal from this position, climate finance would have needed to increase by 78% this year, nearly doubling from a year earlier. In comparison, the accounting changes mean it only has to increase by 2%.

The government says that its accounting changes merely brought it in line with other countries. A Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) spokesperson tells Carbon Brief:

“We will continue to account for all of our international climate finance using internationally agreed OECD guidelines. Meeting our £11.6bn commitment by March 2026 remains our ambition and it is only right that we accurately reflect the funding going to support this aim.”

In response, NGOs and aid experts have argued the UK should have retained its former position as a leader in climate-finance accounting standards, rather than aligning with the looser methodologies used by many others, such as Germany and France.

Moreover, the £11.6bn goal was meant to be a doubling of the government’s previous £5.8bn target, which was based on the original accounting methodology. If the previous target had also been based on a broader definition of climate aid, then the current £11.6bn target would have needed to be higher to represent a doubling.

As the UK nears the end of its third five-year ICF target, it is expected to announce another goal covering the period 2026-27 onwards. This will feed into the $300bn global climate finance target that nations agreed at the COP29 climate summit last year.

Amid the aid cuts, climate NGOs say that the accounting changes should be reversed and the UK should turn to “polluter-pays” measures to generate the required public funds. Catherine Pettengell, executive director of Climate Action Network UK, tells Carbon Brief:

“Our main concern is that we now have the spending review, but there is still no clarity – or vision – on current or future climate finance from the UK.”

Big investments

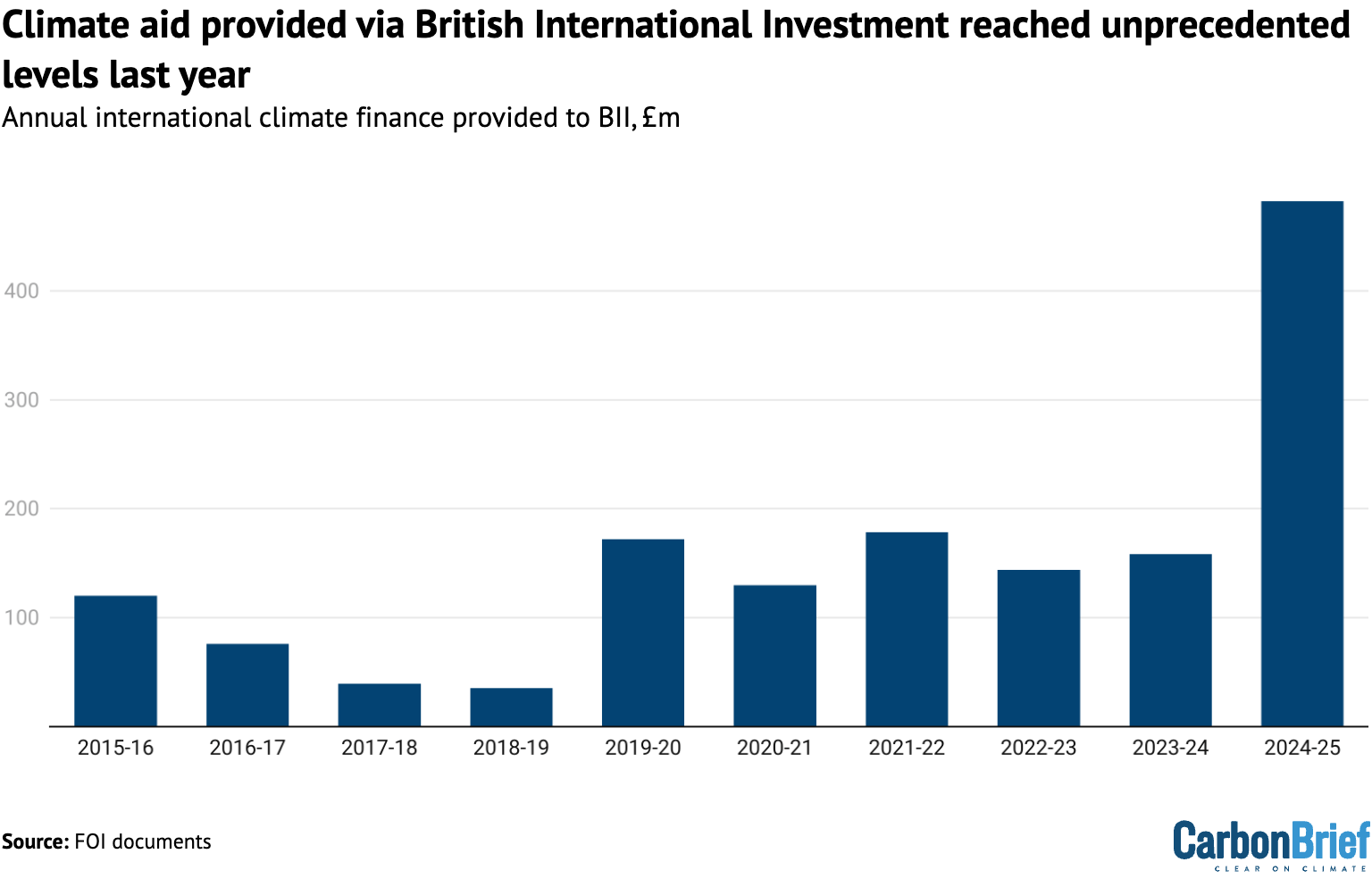

The UK is now leaning heavily on private-sector investments to achieve its climate-finance goals, according to Carbon Brief’s analysis.

By far the largest climate-finance input last year was a £482m contribution to the UK’s development finance institution, BII.

This is the biggest climate-finance contribution the UK has ever made in a single year, according to the data that Carbon Brief has collected in recent years.

It also amounted to nearly a fifth of the total climate finance last year and almost three times more than the UK has ever channelled into BII before.

BII is a publicly owned, for-profit company that largely supports itself with its £7.3bn portfolio of investments in developing countries, but it also receives regular injections of aid money.

The surge in BII climate finance last year can be attributed to two things.

First, the government now counts more of its BII investments as climate finance than it did previously, following the accounting changes. It argues that this more accurately reflects BII’s expanding focus on investing in clean-energy projects overseas.

The government also decided to invest an extra £400m – largely from underspending on housing asylum seekers in the UK – into BII, bringing its total budget for the year up to £881m.

Prior to these changes, the government expected BII climate finance to be worth £126m in 2024-25, according to forecasts previously obtained by Carbon Brief.

It has, therefore, added an extra £356m to BII’s contribution. Carbon Brief estimates that £218m of this can be attributed to the accounting changes, rather than the increase in funding. (See: Methodology.)

Critics argue that BII, which focuses on loans and equity finance rather than grants, is not capable of supporting climate action in the poorest and most climate-vulnerable nations. (Separately, it has also been criticised for continuing to support fossil-fuel developments.)

Last week’s spending review provided the FCDO with at least £300m annually out to 2029-30 for BII and similar organisations, even as billions are cut from its aid budget. In this context, Ian Mitchell, a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development, tells Carbon Brief:

“BII looks set to become the government’s main climate-finance vehicle. Though, whether this is compatible with its historic focus on Africa and the poorest countries remains to be seen.”

Meanwhile, the biggest single project to receive funding from the UK last year was the World Bank initiative titled: “Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE).” The government provided it with an initial contribution of £154m.

SCALE aims to help around 20 countries generate carbon credits that can be sold by companies on the voluntary offset market or internationally via Article 6 carbon markets.

According to the UK government, one aim is to “maximise the mobilisation of additional finance through the sale of carbon credits”.

Selling carbon offsets has long been touted as a way to channel climate finance into developing countries, but the practice has faced intense scrutiny and accusations of “greenwashing” in recent years.

Accounting changes

Other large portions of funding in the UK’s 2024-25 climate-finance budget can also be attributed to changes in the government’s accounting methodology.

For example, as of 2023, the UK started counting portions of its “core” payments into MDBs as climate finance, significantly inflating its climate-aid total.

This money is used by the banks to issue loans and – to a lesser extent – grants for projects in developing countries. While many of these projects will be climate-related, relabelling some of the UK’s contributions as “climate finance” does not result in any additional funds being distributed.

In 2024-25, this relabelling accounted for at least £103m of the total climate finance, including £84m for the African Development Bank (AfDB), £11m for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and £8m for the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) Special Development Fund.

In terms of bilateral aid from the UK, several of the projects with the largest share of climate finance last year were in nations facing war, famine and natural disasters.

This can partly be attributed to accounting changes that mean 30% of all humanitarian funding in the most climate-vulnerable countries – including Afghanistan, Sudan and Somalia – is now automatically counted as climate finance within government accounting.

Some of these nations have, therefore, risen to be top recipients of bilateral “climate aid” from the UK – as shown in the figure below – through programmes such as Sudan Humanitarian Preparedness and Response.

(Such programmes tend to involve the UK supporting NGOs rather than providing funds to governments. For example, FCDO has two “flagship” humanitarian programmes in Afghanistan – both with an ICF component – but does not provide funds to the Taliban.)

This accounting change was viewed by the previous Conservative government as a way to avoid a “trade-off” between climate and humanitarian projects, amid aid budget cuts.

As the map above shows, Ethiopia remained the largest recipient of UK climate finance via single-country projects last year, with £92.3m in total. This has been the case for more than a decade.

The finance largely comes from two programmes, which aim to improve climate resilience in regions of Ethiopia that have been afflicted by drought and flooding. The country has faced years of regional conflicts that have been exacerbated by climate shocks.

Rather than directly supporting individual projects in individual countries, most UK climate finance is distributed to international bodies and initiatives that serve many countries.

Some of the biggest payments are to well-established international grant providers. These include £227m for the Green Climate Fund, £64m for the Global Environment Facility and £26m for the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF).

Other large payments went to long-running initiatives to help “build financial markets and institutions” in Africa and “mobilise private investment in infrastructure” in developing countries.

Methodology

This analysis is the latest part of Carbon Brief’s efforts to assess the UK’s ICF contributions by financial year. Detailed data underpinning these contributions is not released publicly, but is required to track progress towards the UK’s ICF targets.

Total ICF figures for the years 2011-12 to 2023-24 are based on summary public statements made by the government. Ministers have quoted different figures on different occasions, but Carbon Brief is using a March statement from FCDO minister Stephen Doughty for the 2011-12 to 2023-24 period, as this is understood to be the most up-to-date.

The figures for 2024-25 are based on FOI responses from the three major departments responsible for the UK’s overseas climate-related aid projects: FCDO, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Around 80% of climate finance provided by the UK is overseen by the FCDO.

All three of these departments provided the data for 2024-25, stressing that it is provisional. This means it is “subject to year-end accounting and audit adjustments, which are still being processed”. Carbon Brief also received the final (i.e. non-provisional) figures for 2023-24, having been given the provisional figures last year.

(The provisional figures released to Carbon Brief in 2023-24 last year were significantly lower than the final figures – amounting to £1.8bn rather than £2.3bn. This is almost entirely due to the provisional data not factoring in most of the accounting methodology changes described in this article. The provisional figures for 2024-25 appear to have factored in these methodology changes already.)

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) also oversees a small number of ICF projects overseas. Unlike the other departments, DSIT rejected Carbon Brief’s FOI requests. Carbon Brief understands that its projects were worth £42m in 2023-24, roughly 1% of the total. For the sake of this analysis, Carbon Brief assumes that this amount remained the same in 2024-25.

Carbon Brief relied on previous FOI results to calculate how much of the UK’s climate finance derives from accounting changes in recent years:

- BII: According to an internal document, under its old methodology, the government originally forecast 30% of BII core capital to be climate finance in 2024-25, amounting to £126m. The final figure provided to Carbon Brief, which is also based on a higher core capital figure, is £482m. If the government had counted 30% of the higher core capital contribution as ICF, under its old methodology, the total would be £264.3. This suggests the remaining £218m of the £482m could be attributed to the methodology changes.

- MDBs: The FOI results provided to Carbon Brief show contributions to the AfDB, ADB and CDB amounting to £103m.

- Humanitarian projects: Carbon Brief has used the estimates from an internal document showing how much climate finance the government expects humanitarian aid projects to provide, including £69m in 2024-25. This may be an underestimate, as some of the projects listed in this document have higher ICF totals in the new FOI data released to Carbon Brief.

- “Scrubbed” projects: The government also asked civil servants to reappraise the existing aid portfolio in order to identify any extra ICF that could be counted. Carbon Brief has obtained an incomplete list of these projects, which states that £138m was added to the 2024-25 total in this way.

Together, these changes add up to £528m. The actual figure may be higher, as these are provisional figures.

Carbon Brief’s estimate of the cumulative impact of the accounting changes by 2024-25 – some £1.3bn – aligns with an estimate of £1.72bn for the entire five-year period out to 2025-26, made by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). The final figure may be higher, as ICAI’s calculation was based on government documents that did not, for example, include the increased capital contribution to BII in 2024-25.