COP29: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Baku

Multiple Authors

11.24.24Developed nations have agreed to help channel “at least” $300bn a year into developing countries by 2035 to support their efforts to deal with climate change.

However, the new climate-finance goal – agreed along with a range of other issues at the COP29 summit in Baku, Azerbaijan – has left developing countries bitterly disappointed.

- COP29: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Baku

- COP29: Five key takeaways from Brazil’s 2035 climate pledge

- COP29: Six key reasons why international climate finance is a ‘wild west’

- Analysis: Which countries have sent the most delegates to COP29?

- Interactive: Tracking negotiating texts at the COP29 climate summit

- Interactive: Who wants what at the COP29 climate change summit

- COP29: What is the ‘new collective quantified goal’ on climate finance?

- Guest post: How COP29 host Azerbaijan could boost growth through climate action

They were united in calling for developed countries to raise $1.3tn a year in climate finance.

In the end, negotiators agreed on a looser call to raise $1.3tn each year from a wide range of sources, including private investment, by 2035.

Some countries, including India and Nigeria, accused the COP29 presidency of pushing the deal through without their proper consent, following chaotic last-minute negotiations.

Countries failed to reach an agreement on how the outcomes of last year’s “global stocktake”, including a key pledge to transition away from fossil fuels, should be taken forward – instead shunting the decision to COP30 next year in Brazil.

They did manage to find agreement on the remaining sections of Article 6 on carbon markets, meaning all elements of the Paris Agreement have been finalised nearly 10 years after it was signed.

Negotiations were overshadowed by the reelection of Donald Trump, who has promised to roll back climate action and take the world’s biggest historical emitter out of the Paris Agreement once again.

COP president Azerbaijan – a country that sources two-thirds of its government revenue from fossil fuels – faced accusations of conflict of interest and malpractice, with one minister labelling its hosting style “deplorable”.

Here, Carbon Brief provides in-depth analysis of all the key outcomes in Baku – both inside and outside the COP.

- Formal negotiations

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of COP28, COP27, COP26, COP25, COP24, COP23, COP22, COP21 and COP20.)

Formal Negotiations

Azerbaijani leadership

Azerbaijan was announced as the host of COP29 towards the end of COP28 in Dubai. The COP presidency is rotated around the world over a five-year cycle, with Azerbaijan being chosen this time to represent the eastern European region.

The decision came later than normal. Russia had vetoed any EU member in eastern Europe taking up the presidency, leaving just Azerbaijan and Armenia as viable options. Armenia initially vetoed Azerbaijan based on the long-standing conflict between the two countries.

Eventually, Armenia withdrew its candidacy and lifted its veto on Azerbaijan, in exchange for the release of 32 Armenian prisoners. (Armenia has since been chosen to host the COP17 biodiversity summit in 2026.)

Carbon Brief analysis found that more than 65,000 delegates registered to attend COP29, with Azerbaijan having the largest delegation totalling 2,229 people. (See the analysis for a full breakdown of who attended COP, including, for the first time at a COP, analysis of which media outlets sent the largest teams of journalists.)

The appointment of a “petrostate” as the host of a climate summit – for the third year in a row following talks in Egypt and Dubai – immediately sparked backlash.

Climate Home News reported in May that Azerbaijan pumps less than 1% of the world’s oil and gas, but has an economy that is heavily reliant on fuel production. Fossil fuels make up more than 90% of all exports and two-thirds of government revenue.

On 8 November, ahead of the summit’s opening, a Global Witness investigation reported on by BBC News produced footage of the chief executive of COP29 appearing to be open to using his position of host of the summit to make future oil and gas deals.

In the clip shared by Global Witness, Elnur Soltanov spoke to a man posing as an investor about opportunities to invest in the country’s gas expansion, adding:

“We will have a certain amount of oil and natural gas being produced, perhaps forever.”

The COP29 presidency did not comment on the investigation at the time it was published or when asked about it in daily press briefings.

A separate Global Witness investigation found that at least 1,700 fossil-fuel executives had registered to attend COP29, lower than the record in Dubai but still larger than most party delegations.

On the summit’s first day, the presidency attempted to repeat the UAE’s COP28 day-one “win” on loss and damage by pushing through a deal on Article 6.4, which governs international carbon trading. (See: Article 6.)

However, Drilled reported that many parties felt the fast adoption process did not allow time for proper consultations, with one negotiator describing it as a “horrible precedent”.

Following the end of COP29, Carbon Brief ran a webinar to answer questions from the audience about the key outcomes from the summit.The summit’s first day also saw the presidency land in a lengthy fight over what should be on COP’s official agenda.

The fight reflected the key battlelines at the summit: a new climate finance goal; and how, where – or even whether – to carry forward COP28’s deal on “transitioning away from fossil fuels”. (See: UAE dialogue and the global stocktake.)

See where countries stood on the key issues in Carbon Brief’s interactive table of who wanted what from COP29.

At the opening of the World Leaders Climate Action Summit on the conference’s second day, Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev brought renewed focus on the country’s fossil-fuel interests by using his intervention to describe oil and gas as “a gift of god”.

Aliyev also criticised “western fake news” about his country’s emissions and chose not to announce its new UN climate plan, as widely anticipated.

This is despite Aliyev’s government going to “bizarre” lengths to prepare Baku for COP29, reported Bloomberg. This included clearing public areas and roads by moving parliamentary elections, shutting schools and universities and ordering two-thirds of the workforce to work from home, according to the publication.

The next day, the presidency suffered two headline-grabbing diplomatic blows.

The government of Argentina, led by right-wing populist Javier Milei, decided to withdraw its delegation, reported the Latin American publication Climática. There was speculation that the move was intended to woo incoming US president Donald Trump, but this was never confirmed.

In addition, France’s top climate official, ecological transition minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher, told the French Senate that she would not be attending the second week of the summit to participate in negotiations following a diplomatic spat with Azerbaijan.

Towards the end of the first week, senior figures including former UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon and former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres wrote in an open letter that the COP process is “no longer fit for purpose” and that countries that do not support the phasing out of fossil fuels should not be able to take up the presidency.

(Figueres later distanced herself from the letter in a LinkedIn post, describing the COP process as “an essential and irreplaceable vehicle for supporting the multilateral, multisectoral, systemic change we urgently need”.)

When asked by a journalist to respond to the idea that the COP process was no longer fit for purpose during a presidency press conference, Azerbaijani lead negotiator Yalchin Rafiyev said:

“It’s better than any alternative, taking into account we don’t have any alternative process. Multilateralism, yes, we agree it’s under pressure. There are a lot of challenges and external complexities.”

At the start of the summit’s second week, focus turned to the presidency’s role in steering the negotiations.

Speaking in plenary, COP29 president Mukhtar Babayev announced that Azerbaijan did not intend to produce a “cover text” for COP29 – a frontpage-style document summing up the main outcomes of the summit.

Many had hoped a cover text would be produced in order to provide a home for the key pledge on “transitioning away from fossil fuels” agreed at COP28. In the end, a reference to this pledge was included in a draft on the UAE dialogue – but countries failed to sign off on the document at the end of COP. (See: UAE dialogue and the global stocktake.)

Babayev also confirmed ministerial pairs for taking the negotiations forward, and announced that Brazil – next year’s COP host – and the UK – the last developed country to host the talks – had been chosen to help wrangle negotiations towards consensus.

The day after the announcement, a UK negotiator said that they were unsure of what their role in helping to guide the negotiations was meant to be.

Towards the end of the summit, it was confirmed that the UK and Brazil acted like a ministerial pairing, holding consultations with parties on how they thought the “balance” of texts agreed should look.

The UK and Brazil communicated the results of the consultations to the presidency, but received little feedback, Carbon Brief understands.

Babayev also used his interventions at the start of the summit’s second week to urge parties to work faster to make progress in the negotiations.

The Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) reported that the presidency “set firm timelines” for several negotiation issues, but that many parties felt these were unrealistic, with one negotiator rejecting the presidency’s schedule as “arbitrary”.

A set of texts were eventually released on Thursday morning, including a streamlined proposal for the new climate-finance goal.

It contained two options for how the goal might be formulated – branded “extreme” and “not representative” of developed or developing country views by one negotiator – and an “X” in the place of a proposed monetary figure, which incensed many poorer nations. (See: New climate finance goal.)

In a bid to address concerns, the presidency held a six-hour “Qurultay” meeting where parties were invited to air their views on the texts face-to-face – likely inspired by the “Majlis” held at COP28.

On Friday – the summit’s final scheduled day – the first presidency draft of the climate-finance text was released, including for the first time a monetary figure. This text also received near universal disapproval.

Negotiations dragged into Saturday. The presidency held lengthy consultations with parties all day, which fast began to unravel when two major developing country groupings – the least developed countries (LDCs) and the alliance of small island states (AOSIS) – staged a temporary walkout over the proposed finance deal and feelings of exclusion from the negotiation process.

The breakdown in negotiations sparked frenzied rumours that COP may end without a deal.

Many drew potential comparisons to the COP16 biodiversity summit in Cali earlier this month. Those talks had finished without a finance deal after a large number of developing-country delegates were forced to catch flights home, leaving parties without the “quorum” needed to reach consensus.

At this time, the presidency’s possible conflict of interest and failure to guide parties towards consensus came under sharp scrutiny. Canada environment minister Steven Guilbeault told the National Observer that the presidency’s “lack of ambition” was “deplorable”.

Pressure on Azerbaijan intensified when the Guardian reported on documents suggesting the presidency had allowed a Saudi Arabian delegate to make direct changes to a negotiating text being circulated on Saturday.

One expert said that allowing preferential access to Saudi Arabia – a country accused of blocking references to fossil fuels from being included in COP29 negotiations – risked “placing this entire COP in jeopardy”, according to the newspaper.

While intense conversations about the texts continued into Saturday, the presidency attempted to push on by beginning the final plenary – first turning to approving non-controversial technical items in front of confused party delegates.

In the meantime, Bloomberg reported that the US, the UK and AOSIS came to a behind-the-scenes agreement on a new draft version of the climate-finance text.

The presidency eventually dropped draft decision texts for the key negotiating issues in the early hours of Sunday morning.

The final plenary resumed, where the climate-finance text was adopted – sparking furious condemnation from developing countries, including India and Nigeria, who described the outcome as a “joke”.

The presidency “clearly decided it would be OK to ‘stage manage’ the adoption” over India and Nigeria’s objections, whereas other interventions had not formally “objected”, said Dr Joanna Depledge, an expert on the international climate negotiations at the Cambridge Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance. She told Carbon Brief:

“The key thing is that NCQG was only objected to by India and Nigeria (which the presidency would have known). So, without a critical mass of countries or groups objecting, the presidency clearly decided it would be ok to ‘stage manage’ the adoption.”

The presidency attempted to reach consensus on the UAE dialogue – the text containing a reference to last year’s agreement to transition away from fossil fuels – but this ended in failure. The text will need to be taken up by parties once again at COP30 in Brazil.

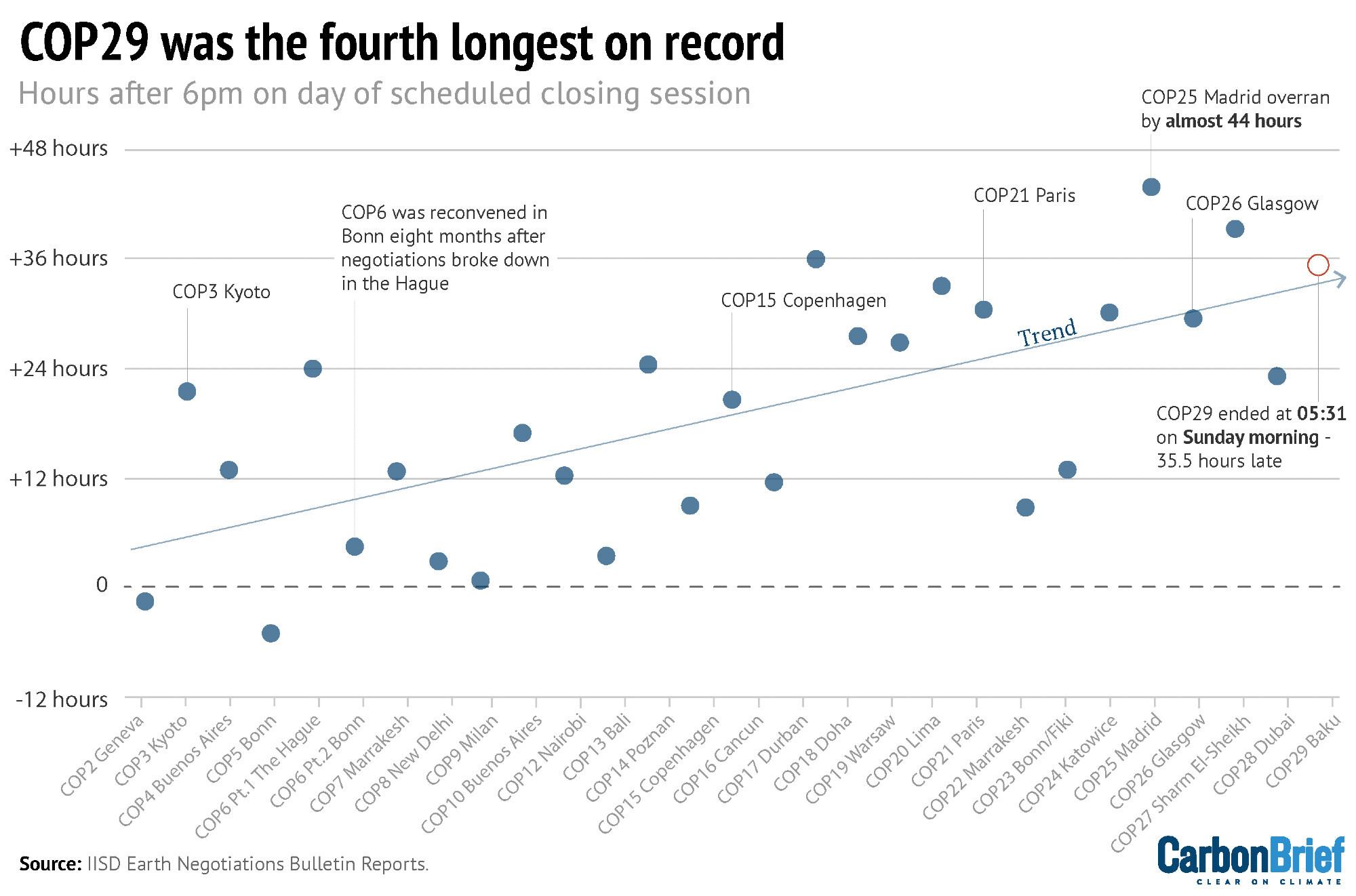

COP29 eventually ended at 5.31am on Sunday 24 November, 35 hours over time.

US election fallout

Just days before COP29, Donald Trump won the US election on a campaign promising to roll back climate action and take the world’s biggest historical emitter out of the Paris Agreement once again.

The potential impact of his reelection on the summit’s negotiations – and multilateralism more broadly – instantly became a major focus on the global stage.

(Carbon Brief analysis earlier this year found Trump’s reelection could add 4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, GtCO2e, to US emissions by 2030.)

Early on in the summit – before negotiations heated up – US climate envoy John Podesta held a press conference where he tried to reassure delegates that president Joe Biden’s outgoing team would continue to play their role at the talks.

At the same time, senior representatives of the EU, the UK and China suggested that their countries would be willing to step into a larger climate leadership role in light of Trump’s election.

The summit’s first week saw right-wing populist leader Javier Milei withdraw Argentina’s delegation from the talks, with some interpreting this as a bid to woo Trump.

The move ignited fears that Argentina might become the first country to follow the US in leaving the Paris Agreement, with some delegates suggesting to Carbon Brief that this could start a chain reaction of far-right governments withdrawing from the global climate deal.

The Argentinian government later clarified it had no plans to leave the Paris Agreement.

As negotiations got underway, the general sense was that all parties were continuing to work together in good faith despite the uncertainty caused by the US election result, one lead negotiator told journalists at a background briefing.

Some said this demonstrated “resilience” in the COP process, whereas others pointed out that it exposed how the talks are inflexible to react to major global events.

In public, countries made a show of reaffirming their commitment to multilateralism. A call for “strengthened multilateralism” was included in a statement from the G20 released during COP and several countries referenced its importance during plenary sessions.

Despite this, Trump’s victory and its hamstringing impact on US negotiators – who are usually viewed as the “powerbrokers” of the conference – was clearly visible in some of the major negotiating tracks at COP29, negotiators and observers said.

South African environment minister Dion George, who co-chaired negotiations on mitigation along with Norway, told Politico that the US was more “subdued” in these discussions, when “normally they talk a lot”.

The New York Times reported that Saudi Arabia, known to push back on new mitigation measures, were particularly emboldened in their stance against including the fossil-fuel transition pledge agreed last year in the COP29 negotiated text.

Some observers speculated that the diminished position of the US – who reportedly helped to convince parties including Saudi Arabia to agree to the fossil-fuel pledge in Dubai – could have played a role.

Trump’s victory also had repercussions for COP29’s biggest aim of agreeing to a new climate-finance goal, others said.

The summit saw developed countries agree to give $300bn a year in climate finance to developing countries by 2035, an outcome that left many global-south nations bitterly disappointed. (See: New climate finance goal.)

Michai Robertson, lead finance negotiator for AOSIS, told Politico that Trump’s victory “changed” what the US “could have provided” – as the outgoing Biden team were in no position to commit to an uptick in spending.

A European diplomat added that the looming arrival of the Trump administration made it “more important” for developing countries to agree to a climate-finance deal at COP29, telling Politico:

“The developing countries [were] saying that it is better to have no agreement than a bad one…Normally, that is true, but, in this case, with the upcoming presidency in the US, it should be crucial for them to have an agreement now.”

However, Dr Leon Sealey-Huggins, a senior campaigner at the charity War on Want, said that the “threat of the Trump presidency [was] being used” to try to convince developing nations to agree to a finance deal, exposing shortcomings in developed nations’ approach to multilateralism. He told Carbon Brief:

“People [were] saying: ‘Well, you better take this money, because when Trump comes, you’re not going to get any money’. And I think that’s a damning indictment of the failure of the political systems in the global north to appreciate that you can’t have a global climate response without global climate justice.”

Moving forward, it is clear that Trump’s victory will continue to affect climate negotiations, observers said – with his administration set to be in place for COP30 in Brazil, a summit being billed as a major moment for increasing global efforts to cut emissions.

New climate finance goal (NCQG)

COP29 launched a new global target for climate finance that will see developed countries “take the lead” in raising $300bn a year for developing countries by 2035.

This is the core of the “new collective quantified goal on climate finance” (NCQG), which nations agreed to establish by 2025 at COP21, when they adopted the Paris Agreement.

It will replace an earlier goal of $100bn per year which developed countries had previously agreed to supply to developing countries.

Finance has consistently been one of the most divisive issues in international climate politics. (For a detailed breakdown of the key disputes ahead of COP29, see this in-depth explainer by Carbon Brief.)

Nations in the global south will need trillions of dollars to transition to cleaner economies and protect their populations from climate change. It is broadly understood that a large chunk of this money will need to come from developed countries.

Under the UN process, only 24 “developed” parties, including the US, the EU and Japan have had to provide climate finance to “developing” countries. They have sought to ease their financial burden by trying to draw in other contributors and the private sector.

This is reflected in the second part of the final NCQG agreement. Developing countries were adamant that they needed $1.3tn a year, exclusively from developed countries. Instead, the text calls on “all actors” to scale up funds from “all public and private sources” to “at least $1.3tn” by 2035.

Unlike the $100bn goal, the new finance goal also leaves the door open for “voluntary” inputs from developing nations that have not previously provided official climate finance, such as China.

These outcomes were the result of intense negotiations that went into overtime, including a walkout by climate-vulnerable nations and last-minute objections by India and others.

Before COP29, the co-chairs overseeing NCQG preparations had whittled down parties’ divergent ideas into a nine-page “substantive framework for a draft negotiating text”. It captured two major options, based on two years of negotiations, “expert dialogues” and meetings between government ministers.

One, favoured by developing countries, involved a target broadly in the trillions that developed countries should channel into developing countries.

The proposal included an option for an inner goal consisting of hundreds of billions of dollars “provided” – meaning public funds. The rest would come from money “mobilised” by these developed countries, which includes private investments triggered by public spending.

There was also an option to only include funds in “grant-equivalent” terms, meaning loans, which make up the majority of climate finance, would not be counted in full.

The other option, backed by developed countries, included a smaller amount of money provided or mobilised for developing countries, but also a larger “investment” goal.

This could cover all sorts of finance, including private investments that have nothing to do with governments. Parties such as the US had even proposed including domestic spending and said it could cover “all global investment” – not just money for developing countries.

Experts say driving climate-related investment in developing countries is essential. But developing countries argue that it is simply beyond the remit of the UN climate process, as AOSIS finance negotiator Michai Robertson told Carbon Brief:

“Right now, we need to be focused on what we agreed to in Paris, which was about providing support to developing countries. If we have a discussion about investments, that has to be some time after we have clearly agreed to this goal.”

Developed countries also wanted this wider goal to include money from relatively wealthy, high-emitting countries, such as China and the Gulf states, that are classed as “developing” in the UN climate system

US climate finance is likely to drop under president Donald Trump. Meanwhile, many European nations have cut their aid budgets, while possible right-wing gains in elections from Germany to Canada next year could further weaken nations’ appetite for overseas climate action.

These major climate-finance contributors have been on the lookout for new donors to fill gaps in a future finance goal. During the first week of COP29, Jacob Levine, special assistant to the US president and senior director for climate and energy at the White House, told Carbon Brief:

“When you consider the magnitude…We need people to contribute, to do their fair share and to recognise the opportunity that we have to work together.”

However, many developing countries have been very clear that they do not want to blur the lines between developed and developing countries in the UN climate process.

In theory, the “substantive framework” could have formed the basis for the negotiations at COP29.

However, as the event started, there was talk among delegates of parties being deeply unhappy with the document. These grievances were comprehensively aired during the opening NCQG talks on the first Tuesday.

Developing countries unanimously rejected the “substantive framework”, with the G77 and China stating that it would not accept the text and requesting a new one. The group pointed to various issues, including the need to exclude certain loans and focus on developed countries providing money, rather than “investment”.

This position was backed by all the key developing-country groups, from the small, climate-vulnerable groups to relatively wealthy, high emitters. For the first time, all the developing countries also coalesced around a demand for $1.3tn per year – a figure first proposed by the African group and LMDCs in 2021.

Some developed countries also expressed dissatisfaction with the text. Many underlined the importance of an investment-based goal in order to ramp up ambition.

The co-chairs agreed to return with a new text, based on parties submitting 65 pages of feedback. By the next morning, a new document had begun circulating and this one had massively increased in size to accommodate all the new inputs.

The text was generally regarded as too large to form the basis of negotiations. Jacob Werksman, the lead EU negotiator, told a press conference that “we are very worried”.

He noted that “literally more than a year of preparation” had gone into the starting nine-page text, only for it to be rejected.

Parties agreed that the co-chairs could try to streamline the document, but must not add or remove any of the key ideas. The new text that emerged that night was just one page shorter. “Clearly, we are way off a landing ground,” Werksman said.

Parties undertook closed-door meetings and, on Friday and Saturday, the co-chairs circulated two versions of a draft text that were shorter, but showed little progress on key issues.

Avantika Goswami, climate programme manager at the Centre for Science and Environment India, told a press briefing that the first week saw “a lot of wasting of time”, with a focus on relatively uncontroversial issues, such as access to finance.

The Saturday text was passed on to the presidency as the first week drew to a close and government ministers arrived to take over the negotiations. Parties were tasked with focusing on “three key issues” – how the goal is structured, how big it is and who has to contribute.

Frustration grew over developed-country groups failing to propose any hard numbers. This was exacerbated by a “declaration” from the G20 summit that merely “look[ed] forward to a successful NCQG outcome in Baku”, rather than providing any firmer guidance.

There was pressure on the EU – the largest provider of climate finance – to step up. Luca Bergamaschi, director of the thinktank ECCO Climate, told journalists that the EU should be a “first mover” and “put something concrete on the table”.

For their part, developed countries argued that they did not want to set a number until they knew who would contribute and what kind of funds would count. EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra told Carbon Brief that, while “affluent” developing countries bore responsibility for providing climate finance:

“For countries, it is typically difficult to leave entrenched positions and move officially from one category to the next. So, a potential solution could be indeed…without leaving these classic positions, to…move into a space of voluntary contributions.”

China, and many other emerging economies, already provide billions of dollars each year towards climate-related projects in developing countries. However, this money is not considered “climate finance” under the UN system.

With China sending positive signals that it was prepared to be more transparent about its overseas climate-related spending, some delegates thought formally recognising these contributions could ease the pressure on the EU and others. (See: China at COP29.)

Bergamaschi told Carbon Brief that, as this money was already being provided, “it’s a political recognition of the reality, essentially, that we need”. AOSIS finance negotiator Robertson told Carbon Brief that counting such money was an “accounting trick” as these contributions are “happening already” and including them would not generate new funds.

With COP29 entering its final days, developing countries proposed a range of core “provision” goals between $440-900bn. These would come exclusively from public, grant-equivalent funds and the rest of the $1.3tn would be “mobilised” by developed countries.

Meanwhile, a potential figure of $200-300bn had begun to circulate, based on Politico reporting of anonymous EU officials. When asked about this target in a press conference, senior figures in the LMDC and G77 groups laughed, asking; “Is it a joke?”

Within the $1.3tn goal, small-island states had also said they wanted $39bn a year carved out for them – and the LDCs asked for $220bn a year. Together, their demands would account for virtually all of the target reportedly being considered by the EU.

The G77 and China had been clear that they wanted “all” developing countries to have equitable access and, when asked by Carbon Brief, African group chair Ali Mohamed said he did not agree with “cherry-picking” certain groups.

As the final Thursday – theoretically, the penultimate day of COP29 – arrived, the presidency published a new text, to widespread disapproval. It contained two options at the more extreme ends of both developed and developing-country positions – and still no numbers.

Civil-society groups said they feared developed countries were holding off on proposing a target as a tactic to ramp up pressure in the closing hours. Linda Kalcher, executive director at the thinktank Strategic Perspectives, told Carbon Brief that the EU’s diverse member states complicated its position:

“If you only get one shot at calling 27 finance ministers, you better get that right and do it at the end.”

On Friday afternoon, mere hours before the COP was officially due to close, a “presidency text” for the NCQG was released, which for the first time contained specific numbers.

The core target was $250bn a year, comprising the same sources as the $100bn and therefore including both “provided” and “mobilised” funds. The broader $1.3tn goal was also included. (Carbon Brief assessed this text in that week’s issue of the Debriefed newsletter.)

While a US state department official said in a statement that the $250bn would require “extraordinary reach”, the goal was viewed as wholly inadequate by developing countries. A rallying cry of “no deal is better than a bad deal” rose up among activists in the corridors.

Analysts pointed out that planned aid spending and existing multilateral development bank (MDB) reforms would already boost climate finance well past $200bn by the 2030s, meaning the goal would require little extra effort from developed countries. Others noted that inflation would wipe out much of its additional value anyway.

The next day, various unofficial leaked texts circulated, including one that increased the core target to $300bn, a move reportedly backed by the EU, the US, the UK and Australia. But, behind closed doors, the G77 and China was pushing for a core goal of $500bn.

A final text emerged at around midnight on Saturday, following urgent diplomatic efforts between major economies and key negotiating blocs. It contained a core goal of “at least $300bn”, as well as the wider $1.3tn from all sources.

Apart from the amount of money, there were a handful of technical details that negotiators were arguing about until the bitter end.

The final text “encourages” – rather the slightly more forceful “invites” in the previous draft – developing countries to contribute climate finance “on a voluntary basis”, and also refers to “voluntary” counting of outflows from MDBs, which developing countries pay into. This wording seeks to address the previously intractable issue of the contributor base.

Technically, developing countries were already “encouraged” to contribute to climate finance under the Paris Agreement. However, language around the $100bn goal itself only specifies “developed” countries should contribute.

This means nations would have had to shed their “developing” identity in order to pay towards the $100bn and, potentially, lose access to benefits this status affords, such as aid.

The NCQG text, by contrast, makes it clear that voluntary contributions count. “This allows countries to opt in…to be contributors to the goal without changing their development status,” Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate in international climate finance at the Natural Resources Defense Council, told Carbon Brief.

Another notable detail was that the draft from the previous day had connected the core goal to Article 9.3 of the Paris Agreement. This paragraph does not contain a strong obligation for developed countries to “provide” money – just “mobilise” it from private sources, MDBs and other sources.

Article 9.1, on the other hand, places the responsibility squarely on developed countries. Civil-society observers blamed the US for this detail, stating that it was trying to shirk its legal responsibility to provide finance.

“If there are legal obligations, [US negotiators] think that makes it something the US congress would have to get involved in,” Brandon Wu, policy director at ActionAid USA, explained to Carbon Brief.

The final text includes a compromise by “reaffirm[ing]” the whole of Article 9 of the Paris Agreement.

The final text also added in some nods to scaling up finance, including specifically grant-based funding, for LDCs and small island states. However, there are no specific finance sub-goals in the text for these groups.

Neither are there specific sub-goals for loss and damage and adaptation, or anything to build on the existing commitment by developed countries to double their adaptation finance, which expires next year. Activities in these areas are broadly underfunded and particularly in need of grant-based, public finance.

The text contains a last-minute addition called the “Baku to Belém roadmap to $1.3tn”, with the vague aim of “scaling up climate finance” and producing a report for COP30 next year. It also commits to “reviewing” the NCQG decision in 2030.

The “roadmap” is derived from a plan announced days earlier by a group of Latin American, African, least-developed and island nations, with the goal of setting out a realistic pathway to the $1.3tn annually that developing countries say they need.

Finally, the text does not resolve the long-standing lack of definition of what “climate finance” includes, which the LDCs said left “the door open for manipulation and inaction”. Early drafts of the text had included “minimum attributes” that climate finance must have, including a note that it must not support fossil fuels – but this was cut.

UAE dialogue and the global stocktake

While COP29 was billed as the “finance COP”, it was always clear that many parties would be loath to leave Baku without a strong statement of climate ambition.

Specifically, many wanted to reiterate, track and embed last year’s COP28 deal under the “global stocktake”, which called on all countries to contribute to “transitioning away from fossil fuels” and to submit climate pledges aligned with the 1.5C limit.

Even before the COP29 summit had formally opened, however, there was a fierce battle over whether, where and how to carry this deal forward.

Ultimately, agreement on this matter was blocked at the last moment, amid complaints from developed and vulnerable countries that the draft text had been so “watered down” as to amount to “attempts to backtrack from the commitments taken last year”.

Moreover, various items that could have resulted in guidance for countries developing their next climate pledges, due by February 2025, were deferred until after this deadline.

The drama had begun brewing at an informal “heads of delegation” meeting convened by the Azerbaijani presidency on the eve of the talks, on Sunday 10 November.

There, despite meeting until around 3am local time, parties had been unable to reach agreement over which items to place on the formal agenda for the two-week summit.

Divisions became clear at the opening plenary of COP29. After a “glossy opening ceremony” and the formal transfer of the COP presidency from the UAE to Azerbaijan, proceedings ground to a halt.

The battle over how to follow up on last year’s global stocktake was at the centre of this “agenda fight”, which was resolved – in classic COP fashion – with a footnote.

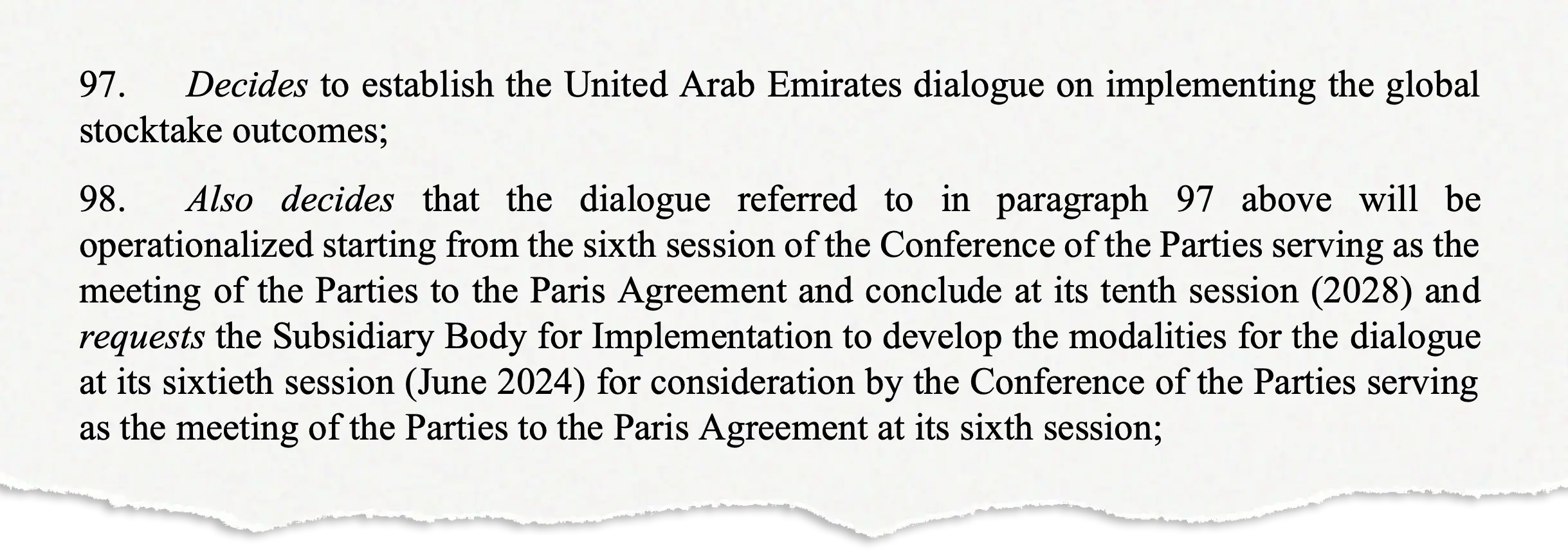

Paragraph 97 of the stocktake established the “UAE dialogue on implementing…stocktake outcomes”, while paragraph 98 asked COP29 to agree on what this dialogue should talk about.

The dialogue had been listed under “matters relating to finance” on the draft COP29 agenda, reflecting its placement within the stocktake outcome text from last year.

While some parties were determined that the dialogue should only discuss finance, others wanted it to follow up on the entire stocktake package, including on fossil fuels.

In a webinar halfway through the summit, Dr Jennifer Allan, senior lecturer in international relations at Cardiff University, said “we’re seeing countries just fundamentally disagree about what they’re supposed to be doing on this”.

In addition to the creation of the UAE dialogue, the stocktake left a series of additional breadcrumbs to be followed up by future COPs. This list includes:

- Paragraph 97: “Deciding” to create the UAE dialogue itself;

- Paragraph 169: “Noting” that parties “shall” explain in their next national pledges (“nationally determined contributions”, NDCs) how the stocktake informed their targets;

- Paragraph 186: “Inviting” relevant work programmes under the Paris regime to integrate the stocktake outcome into their work “in line with their mandates”;

- Paragraph 187: “Requesting” an annual dialogue on how the stocktake is informing NDCs;

- Paragraph 192: “Deciding” to consider how to improve the procedure and logistics of the second global stocktake, based on experience from the first time around.

Parties also fought over whether to reflect the stocktake outcomes in the “mitigation work programme” (MWP; see: Mitigation work programme).

Established at COP26 in Glasgow to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade”, the MWP has been mired in debate over process.

Ultimately – as demanded by Saudi Arabia on behalf of the Arab group – all references to the stocktake were excised from the MWP text.

As each pathway to carrying forward the COP28 deal on fossil fuels appeared blocked, thoughts quickly turned to the idea of carrying the stocktake forward via a “cover text”.

At recent summits, these have been a vehicle for political messages that lack a formal home on the agenda, such as the blockbuster COP26 cover decision to “phase down” coal power.

However, the COP29 presidency consistently opposed the idea, insisting at a stocktaking plenary at the start of week two that all priorities could be tackled via the formal agenda.

Some observers expressed relief at the decision, while others questioned the can of worms that would have been opened if a cover-text negotiation had been started.

At the stocktaking plenary, summit president Mukhtar Babayev reiterated “COP29 cannot and will not be silent on mitigation” and said “we will address the matter in every direction”.

Nevertheless, the block on the MWP and the lack of a cover text left the UAE dialogue as the only avenue for carrying forward last year’s stocktake.

This path was not straightforward. In a pre-COP submission on behalf of the LMDCs, Saudi Arabia had said the dialogue should be “solely focused on finance”.

In contrast, the EU had said the purpose of the dialogue should be to “implement all the mandates of [the stocktake decision] to keep global warming to 1.5C within reach”.

The G20 summit – held in Brazil during the middle of the second week of COP29 – did little to bridge these divides. The G20 leaders’ declaration “fully subscribe[d]” to the COP28 outcome, including the global stocktake, but failed to explicitly mention fossil fuel “transition”.

The EU was far from alone. Negotiating blocs representing more than 125 countries used their plenary interventions on 18 November to call for a meaningful stocktake follow-up.

Samoa, on behalf of AOSIS, said: “We are not prepared to leave…without a substantive outcome on mitigation that allows us to address the agreements we made last year.”

Peru, for the Latin American countries, said: “A key element for AILAC is explicitly including a reference to transition away from fossil fuels.”

These messages were reinforced at a high-level ministerial roundtable on 19 November, notably by COP28 president the UAE – also a member of the Arab group. It told delegates:

“At COP28, for the first time, parties agreed to triple renewables, double efficiency and transition away from fossil fuels in a just orderly manner. We must now train our focus on implementation in Baku and beyond.”

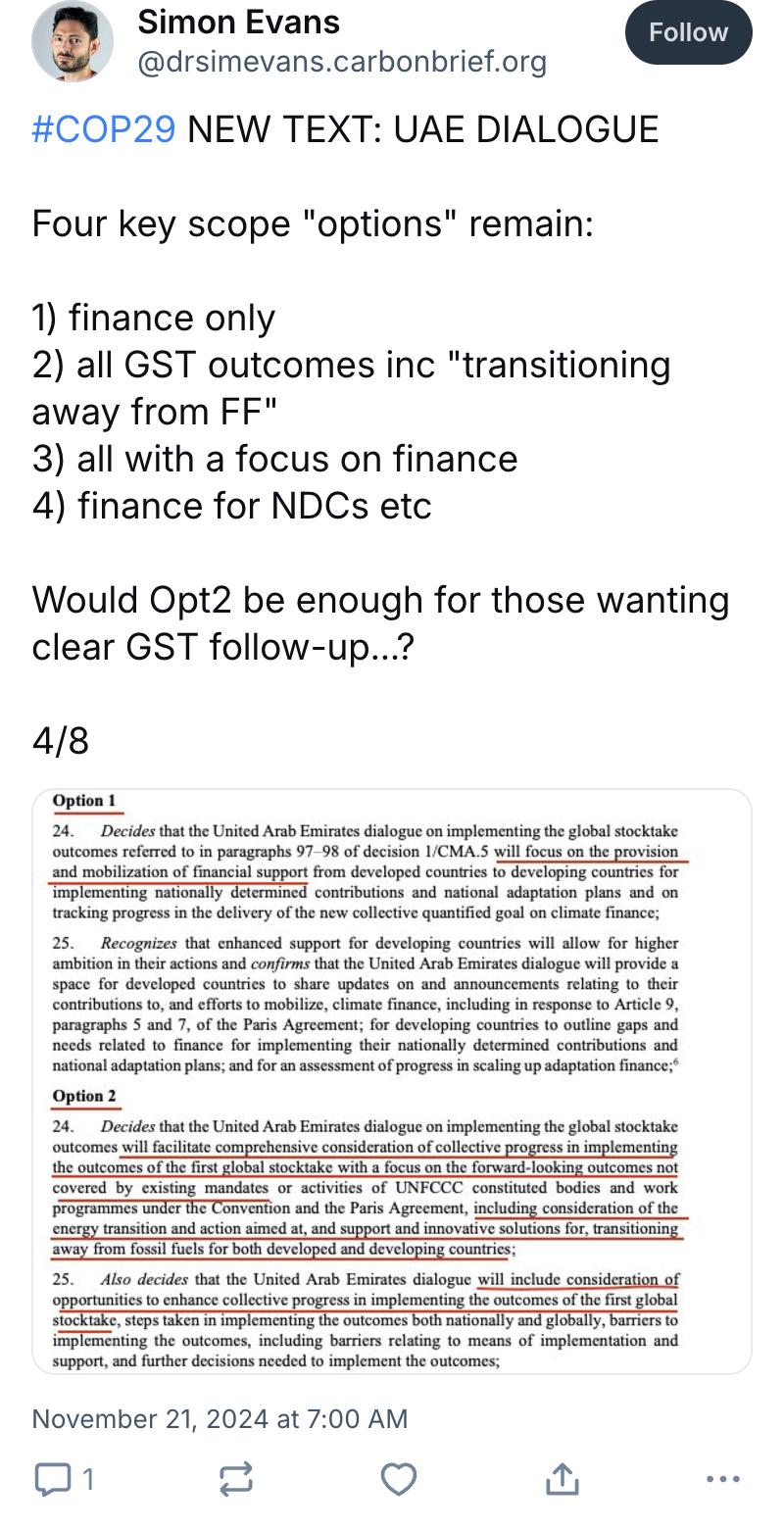

Yet by Thursday 21 November, supposedly the penultimate day of the summit, divisions remained in the package of texts that had been published overnight. Draft text on the scope of the UAE dialogue still contained four options, two of which focused solely on finance.

Later that day, the presidency convened a “Qurultay” to hear responses. (A Qurultay was a “formal consultation meeting of great socio-political importance in Inner Asian history”.)

The marathon six-hour meeting – live-posted by Carbon Brief – witnessed “unanimous” disappointment over the draft package.

Developing countries were unhappy about the lack of numbers on climate finance (see: New climate finance goal) and almost all present called for clearer language on climate action.

New Zealand said it was “unacceptable that mitigation outcomes from [the stocktake] are in danger of being erased”, for example, and the Marshall Islands said: “[We] cannot leave here without an outcome that keeps 1.5C hanging by a thread.”

Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, pushed back on any mention of fossil fuels, saying: “The Arab group will not accept any text that targets any specific sectors, including fossil fuel.” And Bolivia, for the LMDCs, pushed back against a singular focus on the 1.5C limit.

(During the two-week summit, the New York Times reported that Saudi Arabia had been conducting a “yearlong campaign” to “undermine” the fossil fuel text agreed last year. And the Guardian revealed on the final day of COP29 that a “Saudi Arabian delegate has been accused of directly making changes to an official COP29 negotiating text”.)

A new package of texts, published on 22 November, significantly updated the draft of the UAE dialogue. The new version added a clearer “reaffirmation” of the stocktake, specifically including paragraph 28, which calls for “transitioning away from fossil fuels”.

This draft also added options to help implement (paragraph 16) and track progress towards (paragraph 18) the stocktake targets – though both came with options for “no text”.

However, this penultimate draft turned out to have been a high-water mark. A draft decision published just before the closing plenary removed processes to track implementation of the fossil-fuel transition and hooks that would have put the matter firmly on future COP agendas.

Instead, it mooted a two-year “focused exchange of views” on implementation of the stocktake outcomes, which would not even have resulted in a report with key findings.

This draft was not well received during the closing plenary, with AOSIS, the Umbrella Group and the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) all lining up to criticise the state of the text.

Chile, for AILAC, said the text “does not enjoy consensus”.

As a result, COP29 president Babayev proposed that the UAE dialogue be taken up again at talks in Bonn in June 2025, with a view to reaching a deal at COP30 in November.

Reacting to the failure to adopt a deal at COP29 carrying forward the stocktake, Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, told Carbon Brief:

“It’s good that parties rejected a low-ambition mitigation outcome in the final moments of these climate talks, but disheartening they weren’t able to capture the progress of efforts to displace fossil fuels with renewable energy and halt deforestation.”

She added that COP30 in Brazil would have to take that work forward and that, before then, all eyes would be on the new national climate plans due in 2025.

“Vulnerable countries were of the view that it was better not to lock in a weak text,” said Kaveh Guilanpour, vice president for international strategies at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES). However, there is no guarantee of a stronger deal next year.

Naoyuki Yamagishi, energy and climate director for WWF Japan, told Carbon Brief:

“One major risk is losing the momentum of ‘transitioning away’ in the midst of changing international context, including the US situation.”

In addition to the UAE dialogue on carrying forward last year’s stocktake, parties at COP29 also discussed a number of related issues.

They fought over a separate dialogue, held at Bonn in June 2024, where they had discussed how the first stocktake informs their next climate pledges (NDCs).

The EU, small island states (AOSIS) and least-developed countries (LDCs) wanted to use the process to “send a strong signal ahead of the next round of NDCs”, due by February 2025, reported the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

In the end, however, stalled discussions were subject to “rule 16”, meaning there was no outcome and they will be resumed in June 2025 at Bonn.

They had been unable to agree “key messages” from the process – an idea opposed by the LMDCs and the African group – and whether to hold repeat meetings each year.

In a related set of negotiations, parties were unable to agree on further guidance for the next set of NDCs. This means any guidance will come too late for the NDCs due next year.

A compilation of views, published deep into COP29 on 18 November, showed how far apart countries remained on this matter.

AOSIS and Colombia, among others, wanted to see guidance encouraging parties to align their targets with 1.5C. The LMDCs, in contrast, said guidance should not “renegotiate the Paris Agreement” with new “policy-prescriptive elements from the global stocktake”.

Finally, parties were unable to reach a substantive agreement on how to improve the second global stocktake, beginning in 2026, based on experience with the first cycle.

Instead, they reached a procedural decision to pass a heavily-bracketed “informal note” to the next round of talks in June.

Unresolved sticking points included whether to “invite” the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to “align its work” with the five-year rhythm of the Paris Agreement.

The IPCC has already been wrangling with this question and how best to inform the next global stocktake, which concludes in 2028. It is due to finalise its timelines early next year.

Article 6

COP29 finally reached agreement on carbon trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, bringing nearly a decade of negotiations to a close.

The rules governing country-to-country trading under Article 6.2, as well as a new international carbon market under Article 6.4, are now more or less complete.

“It’s time to implement,” said Andrea Bonzanni, international policy director at industry group the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), in a message to Carbon Brief.

The COP29 presidency hailed the agreement as a “breakthrough” that “achieves full operationalisation of Article 6”.

Pedro Martins Barata of the Environmental Defense Fund wrote on LinkedIn that the significance of the deal “cannot be understated”. He wrote:

“For the first time since 2013, we may see the emergence of a viable, UN-backed mechanism to broaden and link carbon markets across the world.”

While carbon markets have a chequered history, the new Article 6.4 “Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism” (PACM) is “significantly different from what’s come before”, said Martin Hession, EU Article 6 negotiator and vice-chair of the PACM supervisory body (SBM).

Speaking at a week-one side event at COP29 attended by Carbon Brief, Hession said:

“We think that we’ve delivered the world’s first Paris-aligned crediting standard.”

However, observer groups continued to voice concerns. Erika Lennon, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), told Carbon Brief this was “overselling it”, adding: “Saying something is Paris-aligned doesn’t make it so.”

Jonathan Crook, policy lead on global carbon markets for NGO Carbon Market Watch, told Carbon Brief that while there are “good elements” in the new rules on methodologies under Article 6.4, aspects of the requirements on carbon removals “have a lot of shortcomings”.

The highly complex talks on Article 6 have seen repeated failure, having broken down without agreement at COP25 in Madrid and COP28 in Dubai.

In Baku, they hit the ground running, after the presidency pushed through a day-one deal endorsing the Article 6.4 documents on methodologies and removals.

While there were some complaints over this process, this was a “distraction” from the substance of the new Article 6.4 mechanism, Hession told Carbon Brief.

This includes a mandatory “sustainable development tool” that offers environmental and human-rights safeguards, downward adjustment of the “baselines” against which carbon credits can be issued and “additionality” checks to avoid projects “locking-in” high emissions.

The work of the supervisory body continues. Before credits can be bought and sold under the PACM, it must approve methodologies for specific types of carbon-cutting activities and receive registrations from projects aiming to implement them.

Also speaking at the COP29 side event, another supervisory body member, Mbaye Diagne, said the first methodologies might be approved in the second half of 2025.

In addition, the SBM is working on further guidelines. Another COP29 decision “encourages” the body to “expedite” its work on baselines, additionality and the risk of removals being reversed, which is a particular concern for “nature-based solutions”, such as reforestation.

The decision also allows afforestation and reforestation projects from the “clean development mechanism” (CDM) – the Paris crediting mechanism’s predecessor – to enter the PACM, subject to meeting rules on removals.

(A separate negotiating track at COP29 was unable to agree to bring the CDM to an end, even though it is now defunct.)

Reflecting on the Article 6.4 deal, Olga Gassan-Zade, former chair of the supervisory body, told Carbon Brief it remained to be seen what difference the mechanism would make:

“Whether it will be able to deliver mitigation at scale or whether it will become yet another expensive toy to virtue signal some parties’ agenda, only time will tell.”

COP29 also reached a decision on Article 6.2, giving a firmer footing to the implementation that is already underway between some countries and giving negotiators a break until 2028.

The decision “requests” more upfront information from countries reporting on their activities. This was a key ask of parties and observers who fear this mechanism could become a “wild west”, where trading can take place with limited transparency.

It also says there can be no changes to carbon credits that have already been “first transferred”, unless this possibility is agreed upfront between both sides of the trade.

Industry groups had said that an unrestricted potential for changes after credits had been bought would make it hard for the private sector to participate in the process.

COP29 reached a messy compromise on the registries that will track the trade in credits. It creates a dual-layer system to cater for countries that lack their own national registry.

Elsewhere, the Article 6.2 deal sets limited consequences for “inconsistencies”. Firmer consequences “would have been a key breakthrough”, Crook told Carbon Brief.

Juliana Kessler, research associate at thinktank Perspectives Climate Research, told Carbon Brief:

“The successful adoption of the Article 6.2 decision in Baku makes a big difference for ensuring more consistent and transparent implementation of cooperative approaches.”

Striking a more cautious note, Christina Hood, head of Compass Climate, told Carbon Brief:

“Sunlight and scrutiny on what units are being traded and how countries are counting transfers toward their targets will matter a lot…There is going to be a critical role for civil society to hold every government to account for high integrity.”

Finally, the talks in Baku agreed a deal on Article 6.8, regarding non-market cooperation.

Mitigation work programme

The mitigation work programme (MWP) was established at COP26 to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade”.

It was formally adopted at COP27, but has since seen limited progress, as negotiators have struggled to deliver more than a series of workshops and exchanges.

At COP28 in Dubai, discussions stalled for days amid divisions over whether it should send high-level political messages or whether that falls outside its mandate.

Much of these disagreements continued at the Bonn negotiations in June 2024, where parties were unable to agree on draft conclusions. Again, the bulk of the disagreement was around the inclusion of substantive or procedural outcomes, with an added fight over whether to create links to the global stocktake agreed in Dubai a year earlier.

Ultimately, negotiations at COP29 ended in deadlock.

Starting on 12 November, MWP negotiations quickly echoed previous meetings, reported Third World Network (TWN). This included disagreements on high-level political messages, the link with the global stocktake and any link to countries’ NDCs.

Paragraph 186 of the global stocktake “invites…relevant work programmes” to integrate “relevant outcomes” of the stocktake into their future work, “in line with their mandates”.

As such, the main bone of contention was whether the MWP should include mitigation actions such as “transitioning away from fossil fuels” as it was a “relevant outcome”, or whether that fell outside of its dialogue-focused mandate.

For China on behalf of the LMDCs and Saudi Arabia for the Arab group, the inclusion of the stocktake or NDCs was a “red line”, Lola Vallejo, co-chair of the MWP, told Carbon Brief. For developed nation blocs, including these elements was key.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Teppo Säkkinen, advisor on climate, energy and industries at the

Finland Chamber of Commerce, said:

“We would hope to see [the] kind of language that is taking forward what was agreed in Dubai, reaffirming that and going a bit further. Not to state new objectives or prescribe, but rather to outline how to get there, to kind of keep the momentum, to carry this forward.”

At the end of week one, parties failed to find consensus on the informal note the MWP co-facilitators had prepared.

Developing country groups, including the LMDCs, the African group and the Arab group, rejected the note saying it went beyond the mandate of the MWP and amounted to using the work programme as a vehicle to “prescriptive, top-down” targets.

In particular, paragraph 32 of the informal note, which referred to the phaseout of coal, fossil-fuel subsidies and the transition to renewable energy, proved controversial.

Reporting on the negotiations at the end of the first week, the ECO newsletter dubbed the disagreements a “pathetic squabble”, adding that “what we have seen in the MWP is nothing short of disgraceful”.

Despite the MWP being subject to “rule 16” as a result – when consideration of an item is not completed and, therefore, is pushed to the next meeting of subsidiary bodies in Bonn the following summer – the presidency revived the programme for the second week.

Speaking in the plenary session on 18 November, the COP president said: “COP29 cannot and will not be silent on mitigation. We will address the matter from every direction.”

Norwegian minister Tore O Sandvik and South African minister Dr Dion Travers George, were chosen by the COP29 presidency as the ministerial pair on mitigation, presiding over the MWP and the UAE Dialogue, wherein the debate about how to carry forward the stocktake also continued. (See: UAE dialogue and the global stocktake.)

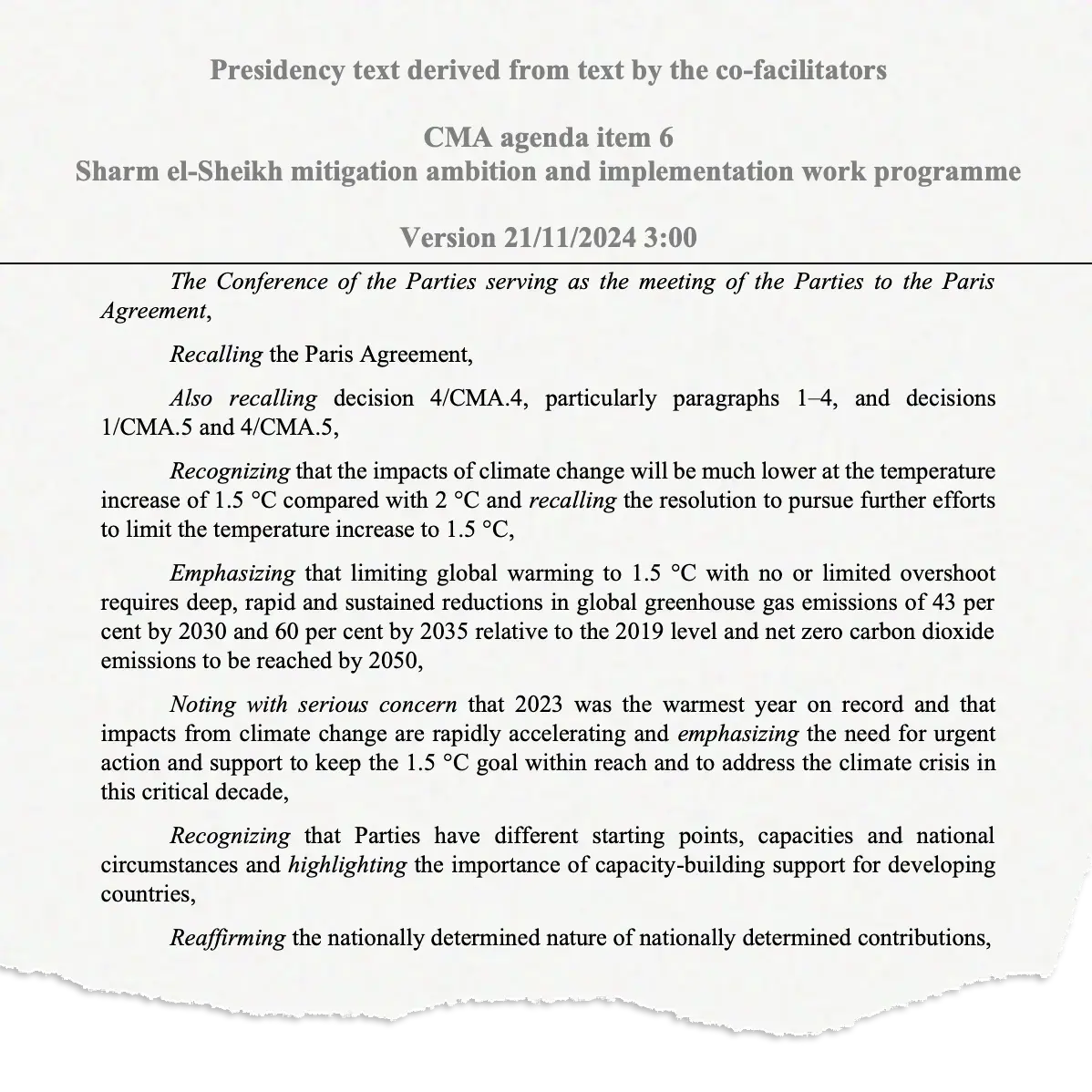

Despite continued negotiations, it was not till 22 November – which was intended to be the penultimate day of the summit – that the first draft MWP negotiating text was released.

The text included no mention of the stocktake or fossil fuels. And, rather than offering guidance on the next round of NDCs, it merely “reaffirmed” their “nationally determined nature”.

In the introduction, the draft high-level comments were, however, fairly strong, “noting with serious concern” that 2023 was the warmest year on record and clearly referencing 1.5C.

The draft was met with criticism from global-north countries who were frustrated by the lack of reference to the stocktake within the MWP text.

During the “Qurultay” plenary session that followed the release of the texts, comments from delegates included:

- LDCs: Called for guidance on how the stocktake can raise ambition in the MWP;

- US: Argued that the stocktake outcomes should form the core of the MWP;

- UK: Said the MWP does not reflect the need to set ambitious NDCs;

- South Africa: Criticised “cherry-picking” of stocktake outcomes in the MWP text;

- Angola: Argued the MWP was not the place for high-level messages.

The following day, a second, “clean” draft negotiation text was released, with no square brackets around passages of text that were subject to disagreement. This was little changed from the previous text and maintained the lack of reference to the stocktake.

However, the preamble was changed, softening the high-level political messaging within it, including removing all references to 1.5C.

Following the release of the MWP negotiating draft text on 22 November, Harry Camilleri, a researcher at E3G, said in a statement that the text “misses the chance to send high-level messages on the NDC update process”.

The text instead focused predominantly on the dialogues undertaken within the MWP, which this year were focused on “Cities: buildings and urban systems”.

It noted the productive conversations had within the MWP on the topic and called for submissions on the topic for further dialogues.

Ultimately, a deal on the MWP was adopted without intervention during the closing plenary, with the only substantive outcome being continued discussions.

It was almost identical to the previous draft, with just a small change referring to the “mobilisation” of financial, technology and capacity-building support to developing countries rather than its “provision”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Lola Vallejo, co-chair of the MWP, said that while much of the focus was on the political messaging under the MWP, a lot of “good work” had been done within the dialogues, adding:

“Countries are willing to talk about what they’re doing and I think that’s really something to hold on to. But, to a certain extent, having a [COP] decision within this process means that inevitably things become very political. So, in some ways, it is the kiss of death to all the good things that we’re doing within the MWP.”

Adaptation

At COP29, there were five areas being covered under adaptation, with national adaptation plans (NAPs) and the global goal on adaptation (GGA) as the most prominent.

At COP28, a “framework” to guide national efforts to protect their people and ecosystems from climate change was adopted under the GGA, in a “historical decision”.

Under this UAE framework for global climate resilience (UAE framework), there are seven thematic targets and four-dimensional targets, focused on everything from water through to cultural heritage.

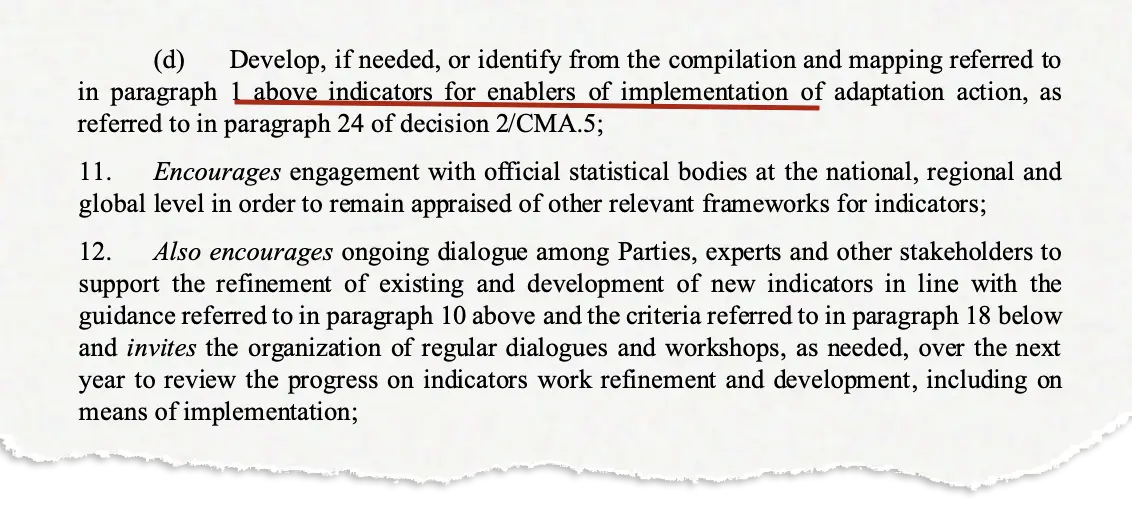

Additionally, the decision in Dubai in 2023 established a two-year work programme dubbed the UAE-Belém work programme on indicators for measuring the progress made and developing indicators for the above-mentioned targets.

With COP29 forming the mid-way point in this programme, “parties ha[d] stressed that a decision in Baku is critical”, stated TWN.

However, after informal consultations on adaptation began on 12 November, divergences quickly emerged over whether there should be indicators on “means of implementation” (MOI) of the GGA targets – generally understood to mean finance – on establishing GGA as a permanent agenda item, as well as on the notion of “transformational adaptation”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, explained that MOI, “although broader language in theory”, is politically understood by parties to mean finance in a “very tangible way”. She added:

“It has always been the case within the GGA that MOI has been understood to be one of the most divisive areas within the negotiations, as it is so essential to mobilising the large-scale adaptation and resilience actions that are necessary for the protection of communities and the natural environment alike.”

Despite “tireless” work across four informal consultations over the first week of COP29, parties could not conclude matters. A draft negotiating text released early on 16 November still included 41 square brackets across its nine pages, indicating areas of disagreement.

Later that day, negotiators decided to forward the work-in-progress draft text to the ministerial-level talks in the second week.

According to TWN, the main points of opposition were developed countries pushing back against the MOI language including its indicators, plus a reluctance by the LMDCs, LDCs, the African group and Arab group to discuss “transformational adaptation”.

To help move the conversation forward, the COP29 presidency announced a new ministerial pairing for adaptation on 18 November. Irish minister Eamon Ryan and Costa Rican minister Franz Tattenbach were appointed.

Throughout “informal informals” in the second week, there was some agreement on deferring the review of the GGA framework until after the second stocktake concludes in 2028. But other disagreements remained – in particular, on means of implementation and transformational adaptation.

Speaking to Carbon Brief ahead of the conclusion of negotiations, Ana Mulio Alvarez, researcher on adaptation at thinktank E3G, said the EU was being “quite difficult”.

This was because it did not want MOI included, as it was trying to balance expectations with regards to finance across the GGA and other tracks, she said. The EU is also in a challenging geopolitical position, Alvarez added, saying:

“They have competing priorities and the US is no longer [once Trump is in power] being a strong partner in climate action. So I would say they’re probably one of the biggest blockers to getting this deal done. In a twist, the UK came out last week in support of MOI. So we’re hoping they build a bridge and can find some criteria for MOI to be included.”

A new GGA text was finally produced on 21 November, with 13 options still remaining, including on the inclusion of MOI and transformational adaptation.

Reacting to the text in the “Qurultay” plenary session, developed nations such as Australia opposed the establishment of MOI indicators for adaptation and emphasised the importance of “transformational” adaptation. Developing countries such as Pakistan and Zambia called for the inclusion of MOI indicators.

The following day, a negotiating text was released without any brackets or options. It “decide[d] to launch” the “Baku Adaptation Roadmap” and put the GGA firmly on the agenda for future meetings.

Language around “means of implementation” was softened, however, to “enablers of implementation” in a move likely designed to appease developed countries.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Jeffery Qi, a policy advisor with the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s resilience programme, explained:

“It’s a compromise. Enablers include MOI, but it also includes things like governance, transparency, anti-corruption etc. So, it’s a mix of developing countries’ MOI demand and developed countries’ enabling conditions demand.

“It definitely adds the connotation of conditionality on receiving support, but it addresses two demands at once.”

While an attempt to bridge divisions in the GGA, some developing countries expressed their disappointment with the change and with the inclusion of transformational adaptation, which they were concerned could create “barriers to access” for adaptation finance.

During the closing plenary, this GGA text was adopted without intervention. The final text includes MOI rather than “enablers of implementation” (although “enabling factors” are mentioned), recognises “transformational” adaptation and launches the Baku Adaptation Roadmap.

Beyond the GGA, NAPs made “significant progress” during the first week, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

While the presidency initially indicated that it would not take NAPs through to the second week as it was only a matter for the technical talks in the first week, this was met with disappointment from various groups.

But with a “constructive atmosphere in the room and that agreement was in sight”, the matter was forwarded to week two for further consultations, according to ENB.

In the second week of COP29, discussions on NAPs gathered “critical force”, according to the G77 and China, although divergent views remained on numerous issues.

On 19 November, a six-page draft negotiations text was published with 158 square brackets in it, highlighting the level of disagreement.

Given time constraints, the co-facilitators leading the negotiations proposed capturing progress in procedural conclusions and continuing the debates in Bonn in June 2025. Ultimately, this proposal was accepted.

Shortly before midnight that day, a final draft negotiating text was published pushing the discussion of NAPs to Bonn, with a view to recommending a draft decision for consideration and adoption at COP30 in November 2025.

An updated six-page draft negotiating text was published the following day, including 159 brackets and 18 options, which will form the basis of discussions in Bonn.

With regards to the other adaptation elements, consideration of the adaptation fund, the report of the adaptation committee and the review of the progress, effectiveness, and performance of the adaptation committee were all pushed to Bonn next year.

Loss and damage

A key issue at recent COPs has been how to raise money to help nations deal with the “loss and damage” caused by climate-related disasters. This came to a head last year with the launch of a “fund for responding to loss and damage” at COP28.

This year, the most politically charged issue relating to loss and damage was the question of whether it should be covered by the new climate-finance goal (NCQG).

Developing countries and climate-justice groups were adamant that loss and damage should be covered by the NCQG, perhaps as a sub-goal within the overall target.

Developed countries were generally reluctant to expand the range of activities that must be supported by the climate-finance target. Loss and damage was not covered by the previous $100bn climate-finance goal.

In the end, parties agreed that loss and damage will not be addressed by NCQG finance.

The final NCQG text mentions “loss and damage” three times, but merely “acknowledges” that “gaps remain” in dealing with it and that it requires public, grant-based finance. (For more details of these negotiations, see: Climate finance.)

The launch of the loss and damage fund at COP28 in Dubai last year was widely celebrated, but attention quickly turned to the task of filling its coffers.

An early presidency-hosted ceremony at COP29 involved signing key documents to enable the fund to finally start distributing money from 2025. Sweden used the ceremony to announce $19m of support and later pledges brought the fund total up from $674m to $759m.

While these pledges were welcomed, the feeling among observers was captured by UN chief António Guterres, who told attendees that the “initial capitalisation” of the fund had not “come close to righting the wrong inflicted on the vulnerable”.

Meanwhile, various negotiations continued to focus on loss and damage. Two strands covered the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), which was established in 2013 at COP19 to help support loss-and-damage activities.

The third “review of the WIM” this year was an opportunity to establish how it works, alongside newer components of loss-and-damage governance, such as the fund and the Santiago Network.

Nate Warszawski, a climate research associate at the World Resources Institute, told Carbon Brief that the last WIM review “catalysed one of the most consequential five-year periods in UN history for loss and damage”.

Parties also discussed the joint report of the WIM’s executive committee and the Santiago Network’s advisory board. Parties decided that COP29 should produce a single decision text combining this report and the WIM review.

There were various areas of disagreement. Developing countries in the G77 and China wanted regional offices for the Santiago network. They pushed for the executive committee to produce guidelines for reporting on loss and damage in official climate plans. In both cases, they faced pushback from some developed countries.

There was also a call from the G77 and China for the creation of a regular loss and damage “gap report”. These documents could mirror the annual “adaptation gap report” produced by the UN Environment Programme, which includes cost estimates.

Developed countries were more hesitant about the creation of such a report, questioning how frequent and detailed it would be.

Ultimately, disagreements meant talks were subject to “rule 16” at the end of the first week. Despite being started up again for week two, ultimately, countries made no more progress and talks were once again pushed back until the June 2025 climate negotiations.

Agriculture and food security

Despite having held more importance at previous COPs and featuring in the global stocktake last year, actual outcomes on agriculture were constructive but relatively muted in Baku.

There is only one formal negotiation track for agriculture and food systems at the UNFCCC, known as the Sharm-el-Sheikh Joint Work on the Implementation of Climate Action on Agriculture and Food Security (SJWA).

At COP29, the debates on the SJWA were largely around the functions and structure of the Sharm-el-Sheikh online portal, where countries and observers can submit information on how climate action can support agriculture and food security.

On the very first day of negotiations, Egypt sought to clarify “how small farmers can make submissions” and called for the website to be more accessible.

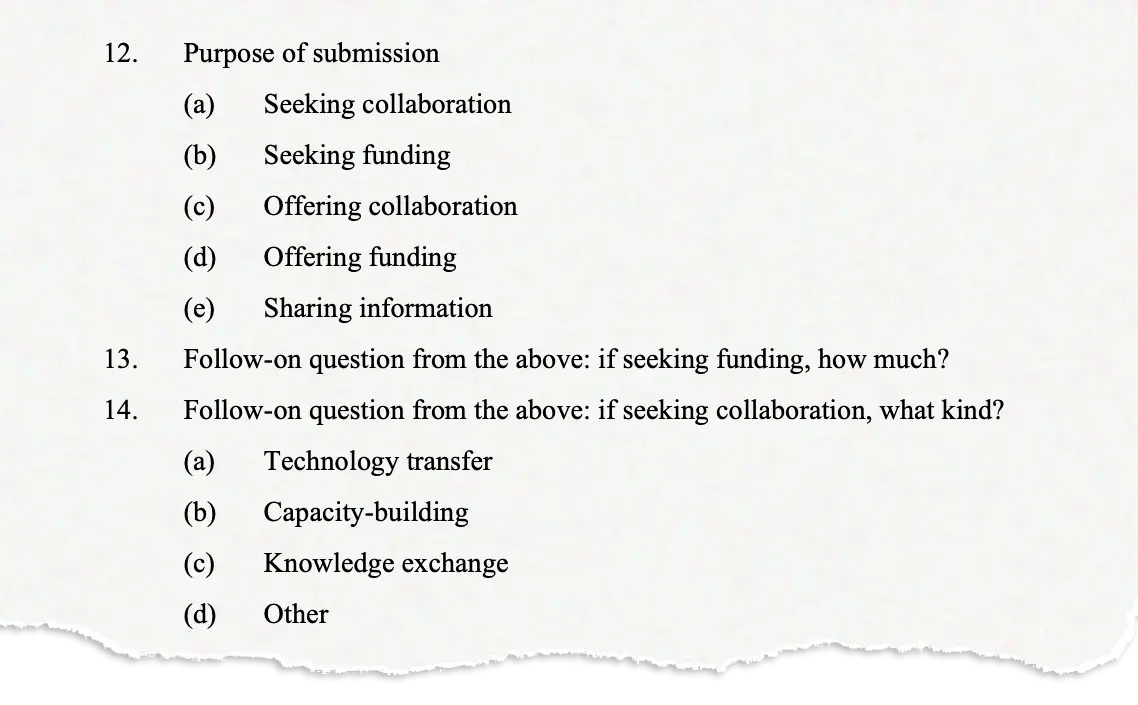

Later, the G77 group led by the Dominican Republic and Kenya proposed “enhancing” the portal to make it more usable, searchable by region and theme, and to allow projects to seek collaboration and finance, such as from the Adaptation Fund.

Carbon Brief understands that, while this was initially resisted by Australia, Canada and the US, countries eventually agreed to consider a submission template developed by the G77 and, later, Australia.

On 15 November, a clean four-page text with no brackets was approved at the mid-week plenary of the subsidiary bodies, wrapping up the negotiating track.

It includes a draft template for submissions and “request[s]” the UNFCCC secretariat to make the portal more accessible and functional, while developing elements, such as how projects can link to financial or practical support.

ActionAid’s global climate justice lead Teresa Anderson told Carbon Brief:

“In all, agriculture served a meagre salad this year. There was a low-key online portal fight and an attempt to get the indicators on agriculture under adaptation to make sense.”

Response measures

At UN climate talks, “response measures” are a forum for discussing the effects of carbon-cutting policies on countries and, as such, are particularly relevant to nations where emissions or deforestation controls pose a risk to their people and economy.

At COP29 in Baku, countries agreed on establishing a four-year work plan to discuss response measures for 2026-2030.

Importantly, the work plan includes an item on the “cross-border impacts” of “measures taken to combat” climate change.

This means that trade-related climate measures – such as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) – now have a formal space to be discussed and their impacts assessed in UN climate talks.

Confirming that this “could be the first time” trade has a seat in the UNFCCC, Tennant Reed, director of climate change and energy at the Australian Industry Group, pointed to a parallel conversation in the World Trade Organization on climate. Reed told Carbon Brief:

“Rather than the way it was in the past, with both forums saying, ‘oh, the other one is the appropriate place to discuss this’, there is some discussion now about to happen in both and more conversation between those tracks would be good, because broadly: the trade people in the WTO don’t know anything about climate, and the climate people in the UNFCCC don’t know anything about trade, and they have a lot to learn from each other and from other stakeholders.”

With ongoing geopolitical and “green-trade tensions” looming over the COP, response measures had assumed agenda-setting importance for the second year.

On 6 November – the day after Donald Trump’s election victory – China submitted a proposal on behalf of the BASIC group to add “climate-change-related unilateral restrictive trade measures” to the COP agenda.

This proposal was one of three items that drove an eight-hour “agenda fight” on the first day of COP29, along with the UAE dialogue and finance. (See: UAE Dialogue.)

Ultimately, the presidency dropped trade measures from the agenda, but committed to consultations on the matter.

According to the COP president speaking at the end of the talks, these consultations amounted to “constructive discussions, [but found] no consensus” on the way forward.

Trishant Dev, a programme officer at New Delhi-based thinktank Centre for Science and Environment, told Carbon Brief:

“Unilateral trade measures in the name of combating climate change absolutely belong in COP discussions. The UNFCCC warns against such measures, yet they continue to be pushed without sufficient scrutiny.”

Adopting a four-year work plan for the response measures forum was seen as essential to COP29’s agenda. Activists and industry observers considered it one of the few “real wins” in Baku.

The final text “encourages” countries to integrate just transition and “decent” job creation in their climate pledges.

This decision captures substantive progress through 2024 by the forum and its council of experts, the Katowice Committee on Impacts (KCI).

Before COP29, the KCI drafted a work plan and recommendations on how countries can promote a just transition in their new climate pledges and better measure and report socio-economic impacts.

KCI experts met in Bonn in May and Accra, Ghana, in September of this year to draft these elements. Of the 161 potential activities listed by experts that could be part of the work plan on impacts, only 17 were adopted in the final text.

Negotiations in the response measures forum were fraught, with developed and developing countries sparring over the optimum “balance” of positive and negative impacts in the workplan.

A draft with eight different options emerged around 3am on the final Thursday of COP29. The draft offered two wording choices – “unilateral measures” or “cross–border impacts” – the former of which was subsequently dropped.

The final response-measures text uses the wording “cross-border impacts.”

In its fiery objection to the final finance goal, India brought up CBAM and “other measures”, adding that “it is quite difficult to enable such a transition in a very, very competitive, hostile environment that we are facing at the moment”.

To Reed, however, the work plan could provide a place where countries can “engage with the substance of how border adjustment really works” and focus on issues such as access to capital and investment in production, “rather than a blanket opposition to do border adjustment as inherently unfair and destructive” to developing countries. Reed added:

“I think familiarity will breed comfort.”

Just transition work programme

COP29 closed without agreement on the just transition work programme (JTWP), in what one observer called a “betrayal of workers, communities, young people and everyone on the frontlines of this transition”.

Last year – despite tense negotiations around whether the programme should be focused on a labour transition or have a broader focus – a text was agreed that for the first time in UNFCCC history (according to observers) established a recognition of labour rights.

However, follow-up talks in June stalled. Developing countries pushed for outcomes that would ensure the programme was more than just a “talk shop”, while developed countries criticised efforts to produce a workplan as being premature.

As talks got underway at COP29, the same divisions began to emerge. The EU and EIG emphasised mitigation in their approach, while the G77 and China pushed for a bigger focus on adaptation and finance, according to WWF.