Bonn climate talks: Key outcomes from the June 2025 UN climate conference

Multiple Authors

06.27.25Multiple Authors

27.06.2025 | 4:20pmClimate negotiators have wrapped up another two weeks of technical talks in the German city of Bonn, seeking to make breakthroughs on critical issues before COP30 in Brazil.

Once again, the UN negotiations were marked by protracted “agenda fights” and calls for developed countries to provide more funding for climate action in developing countries.

This year, the meetings came in the wake of a UN climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, which disappointed many and, combined with the election of Donald Trump as US president, left some questioning the future of multilateral climate negotiations.

The Brazilian COP30 presidency had hoped to see progress in measuring climate adaptation, ensuring a “just transition” for workers and taking forward the “global stocktake” – including its pledge to “transition away” from fossil fuels.

The just-transition talks saw some progress, but there was little convergence on the stocktake and deadlock on adaptation pushed the talks into overtime.

Here, Carbon Brief gives an overview of the key outcomes and disputes at the 62nd biannual sessions of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) subsidiary bodies (SB62).

- ‘Future of the process’

- Adaptation

- Climate finance

- Just transition

- Loss and damage

- Mitigation

- Global stocktake and climate pledges

- Road to COP30

‘Future of the process’

Much of the narrative around the COP29 climate summit in Baku focused on threats to multilateralism. Seven months later, the geopolitical situation has deteriorated further.

Escalating conflict, cuts to foreign aid and efforts by major powers to undermine global institutions all have a bearing on climate politics.

The US, which has withdrawn from the international climate process and did not send any negotiators to Bonn, has loomed large in all of these issues.

In this context – and with 2025 marking a decade since the Paris Agreement – many have started to consider how UN climate talks can be reformed.

This was recognised by the Brazilian COP30 presidency in a letter ahead of the conference, which stated:

“Recognising growing calls for change at COPs, the COP30 presidency invites all parties to reflect on the future of the process itself.”

One strand of the SB62 negotiations dealt with this directly. A note by the UNFCCC secretariat acknowledged the “growing scale and complexity” in climate talks, “particularly with regard to the increasing number of agenda items and mandated events”.

With this in mind, countries used sessions on “arrangements for intergovernmental meetings” (AIM) to discuss how the process could be made more efficient.

Ideas on the table included capping the size of national delegations at 200, “sunsetting” some agenda items and limiting the number of items that could be added to agendas.

Nevertheless, as the talks drew to a close after two weeks in Bonn, Erika Lennon, a senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) told Carbon Brief:

“It seems as though parties wanted to keep discussing ways to increase efficiency as they could not reach agreement on many concrete proposals here.”

Notably, while AIM discussions are normally restricted to SB sessions in Bonn, parties decided that this year they would continue at COP30.

Shreeshan Venkatesh, global policy lead at Climate Action Network International, told Carbon Brief that these AIM discussions were just one part of the wider calls for reform.

“There are deeper questions as well that the UNFCCC and all the parties here need to be a part of…Questions of what it is that is stopping us from making the leap towards transformational progress.”

These ideas were exemplified by a “united call for urgent reform of UN climate talks”, backed by more than 200 civil society groups and released during the SB talks.

One eye-catching proposal from the “united call” is “majority-based decision making” – or voting – if talks fail to reach consensus, which would stop single nations blocking progress. Another idea – following a series of “petrostates” hosting the COP in recent years – is described as “ensuring integrity” of COP presidencies.

In the meantime, existing negotiating tracks continued as normal at SB62. The chairs of the two SBs, Adonia Ayebare from Uganda and Julia Gardiner from Australia, released a joint note ahead of the talks calling for “swiftly advancing” technical work, stating:

“With over 50 agenda items and over 30 mandated events, focused and efficient work at SB62 will be essential.”

Despite this plea, talks did not get off to a good start, as an “agenda fight” delayed them by two days. This followed an attempt by Bolivia, on behalf of the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) – a group that includes China, India and Saudi Arabia – to introduce two additional agenda items.

One, which was backed by the developing-country coalition of the G77 and China, focused on encouraging developed countries to provide more climate finance from their public coffers. The other raised the issue of “unilateral trade measures”, such as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

(This is far from the first time agenda disputes have delayed UN climate talks. At the Bonn sessions in 2023, the agenda was only agreed the day before the event ended.)

In the end, a compromise was reached where both proposals were not added to the agenda, instead being reflected elsewhere in the negotiations. (See: Climate finance and Just transition.)

With all the elements of the Paris Agreement finally operational, the COP process is now meant to be geared towards action, as Alden Meyer, a senior associate at E3G, told journalists on the final day:

“There’s no real central negotiating issue, the way there was in Baku [or Dubai]…So it’s really going to be these real-world impacts that people will measure in Belem.”

The COP30 presidency spoke to this need with another letter, released during the first week of Bonn, which set out an “action agenda” consisting of 30 “key objectives” for the summit.

These objectives are very broad, including some that nations have already agreed at previous summits – such as “tripling renewables” and “transitioning away” from fossil fuels – as well as everything from “water management” to “promoting resilient health systems”.

Adaptation

Global goal on adaptation

Adaptation came to the fore at the Bonn negotiations, with the decision on the “indicators” within the global goal on adaptation (GGA) of particular significance.

Unlike for mitigation, where there are clear metrics of progress relating to national and global greenhouse gas emissions, there have never been any concrete and measurable indicators to track countries’ collective efforts to adapt to a warming climate.

In 2023, parties in Dubai agreed to an overarching framework for the GGA, which defined targets to guide action in key areas, such as food, water and health.

Parties also launched work to define the indicators that can be used to measure progress on adaptation, with 2025 as the deadline for these quantifiable targets.

At one point, there were as many as 9,000 potential indicators on the list.

Going into Bonn, these had been “miraculously” refined down to a list of 490 potential indicators. Still, this was a long way from the aim of agreeing 100 indicators at COP30.

A mandated event took place on the first day of Bonn, despite the agenda fight, within which eight experts ran through the work they had done on the indicators.

While parties broadly welcomed this work, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB), time-consuming problems quickly emerged.

Parties had only been provided with consolidated reports of the experts’ work on the indicators. As such, questions emerged over aspects that were covered in the full reports, slowing the process, one observer told Carbon Brief.

Following the event presentations, negotiations got underway. Debates covered the inclusion of “means of implementation” (MoI) – meaning climate finance – as well as whether the consolidated list of 100 indicators being aimed for should include a headline and subhead structure. Parties also discussed the timeframe of events that would follow Bonn.

MoI has long been a challenge for the GGA, as it broadly refers to financial support from developed countries to support introducing adaptation measures in developing countries.

However, Prof Lisa Schipper, a professor of development geography at the University of Bonn and IPCC author, told Carbon Brief that MoI was core to the GGA:

“It has always been a very challenging agenda item, because…it’s essentially about making sure that there’s finance for adaptation. The idea of the goal is to set a kind of a marker, so that you can say, ‘Okay, this is how much adaptation we need, this is how much we have, this is where the gap is and therefore this is how much money is needed’, right? So that’s kind of the main purpose of it.”

In particular, following on from COP29 as the “finance COP”, which saw a “new collective qualified goal” (NCQG) for international climate finance receive mixed views, questions around funding for adaptation filtered through all of the negotiations within this workstream.

Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, told Carbon Brief as negotiations in the second week of Bonn got underway:

“In general, what we’re seeing this week is the real legacy of the NCQG coming up everywhere. It has come to a head in every negotiating room. It is clear this is what happens when you don’t make adequate financing decisions at COP29. It leads to a week of moderately successful negotiations in week one, followed by stalling and deadlock over finance decisions going up to the wire.”

The divisions over whether to include MoI within the indicators for the GGA followed familiar patterns. Broadly, developed country parties expressed “dislike” for such indicators, while developing countries emphasised their importance.

Other financial elements within the potential list of indicators were also points of division, including those tracking domestic budget allocations.

Prof Schipper told Carbon Brief that there is a “really serious” issue in these discussions on the question of sovereignty. She said that developed countries are asking developing countries to disclose how much of their own budgets they are spending on climate action, including adaptation. This information could then be used against developing countries when they ask for assistance, she explained. Schipper added:

“I think this is really a colonial practice…Countries create climate change and then make the countries that are most affected jump through these hoops, just to get access to funding.”

G77 and China highlighted what they said was a widening adaptation “finance gap”, according to TWN.

At the 2021 COP26 summit in Glasgow, countries had agreed a goal to double the provision of climate finance for adaptation between 2019 and 2025.

A UN Environment Programme report from 2024 found that public adaptation finance flows to developing countries had increased from $22bn in 2021 to $28bn in 2022 – the largest absolute increase and relative year-on-year increase since the Paris Agreement. Yet it noted that even if this trend continued and the doubling goal were achieved by 2025, this would still only meet about 5% of the adaptation finance needed.

With that doubling goal coming to an end in November – and developed countries set to fail to meet it – there were calls for a new goal to triple adaptation finance that filtered through GGA and other adaptation negotiations, as well as actions from civil society groups that took place in the corridors.

A first draft text was published on 19 June, which included a number of options on key points, including the structure of the indicators, MoI and access to and the quality of finance.

Agreement did emerge on having a globally applicable list of headline indicators, which will be complemented by a more context-specific set of sub-indicators to choose from.

However, it remained unclear whether – and if so when – further workshops would take place ahead of COP30, to continue work on these indicators, noted ENB.

As talks continued to progress, discussions also turned to other key elements of the GGA: the Baku Adaptation Roadmap (BAR) and the inclusion of “transformational” adaptation. (This is the idea that fundamental change to the socio-ecological systems that currently exist is required, to truly adapt to global warming.)

There were diverging views on what the BAR should do, what its mandate is and even what evidence there is for needing to create it, as well as its relationship with other agenda items such as the “global stocktake”. Some called for a synthesis report on party submissions on the roadmap, while others pushed for postponing it until COP30.

Similarly, with transformational adaptation, it seemed little agreement could be found. Grupo Sur, for example, stated that the understanding of the concept and what it would entail was not yet sufficiently mature to allow for informed discussion.

Prof Schipper explained that there are wider problems with the concept of transformational adaptation, adding:

“We don’t know how to implement it. [Transformational adaptation] would be the kind of adaptation that really changes the systems and really questions power structures and so on. Of course, no government wants to have those kinds of things coming up. So they got sidetracked by this.”

As the first week’s negotiations came to a close, there were significant disagreements within the GGA discussions in particular on the timelines for work on the GGA indicators, the inclusion of MoI or other financial referencing and both BAR and transformational adaptation.

The ECO newsletter, produced by Climate Action Network, criticised negotiators for “dawdl[ing] over timelines and quibbl[ing] over technicalities”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief at the beginning of the second week of Bonn, Emilie Beauchamp, lead for monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) for adaptation at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), said that given time constraints, there were just “too many” aspects to discuss under the GGA. She added:

“We haven’t had time to discuss fully [the BAR, transformational adaptation and the other aspects of the GGA], so there are many divergences still. Cutting corners on process could risk tricky issues exploding at COP – and issues linked to MoI and finance will definitely still show up in Belém.”

A second draft text was produced on 24 June, as time began to run short at Bonn. This contained many elements that were still bracketed – showing points that are yet to be agreed – or listed as options.

Talks on this draft ran late into the night, with co-facilitators noting that progress was being made. However, haggling over MoI resurfaced on the penultimate day.

This to-and-fro mirrors the GGA negotiations in Baku, when there was a push to soften language from “means for implementation” to “enablers of implementation” or other terms.

Parties eventually agreed to task co-facilitators with streamlining the text further on the indicator guidance, while leaving other sections unchanged.

Throughout the final day of Bonn, negotiations continued. The official end time of SB62 came and went without an agreement on the GGA.

A text outlining draft conclusions on the GGA did not get uploaded until mid-way through the final plenary, causing complaints from parties about their ability to review the contents before it was gavelled through.

Sections on the BAR and transformational adaptation were removed from the draft conclusions, with a final paragraph noting that instead they will be captured in an informal note, which will be used as the basis of negotiations at COP30.

The text in the informal note is identical to that from paragraph 21 down of the previous draft text, meaning there are many outstanding elements in brackets or listed as options – there are still eight separate options for the text on the BAR, for example.

Observers told Carbon Brief that it was unsurprising that the text got split, with BAR and transformational adaptation only captured as an informal note. These elements are not time sensitive and there was a general agreement that the GGA indicators were the priority.

On MoI, the draft conclusions replaced multiple options that had been in paragraph 15 of the previous version with language stating that “indicators for means of implementation and other factors that enable the implementation of adaptation action are to be included, and those that are not relevant to the Paris Agreement are to be removed”.

Lina Yassin, a researcher at IIED who provides support to the LDC Group, told Carbon Brief that paragraph 15 remained a sticking point throughout 25 June, but was “crucial” for developing countries.

Developing countries want MoI to be “grounded” in the Paris Agreement, Yassin explained, whereas developed nations prefer what she called “weaker language from the Baku decision that frames MoI as merely one type of ‘enabler of adaptation’”.

Yassin added that the text adopted in Bonn was a “compromise” but still contained “important gains for developing countries, especially in moving away from the ambiguous Baku language”.

Importantly, the text invites experts to continue working on the indicators, to submit a final technical report and list of potential indicators to the secretariat in August 2025.

This will allow further negotiations at COP30 to further whittle down the list of indicators under the GGA, towards the 100-indicator goal.

NAPs

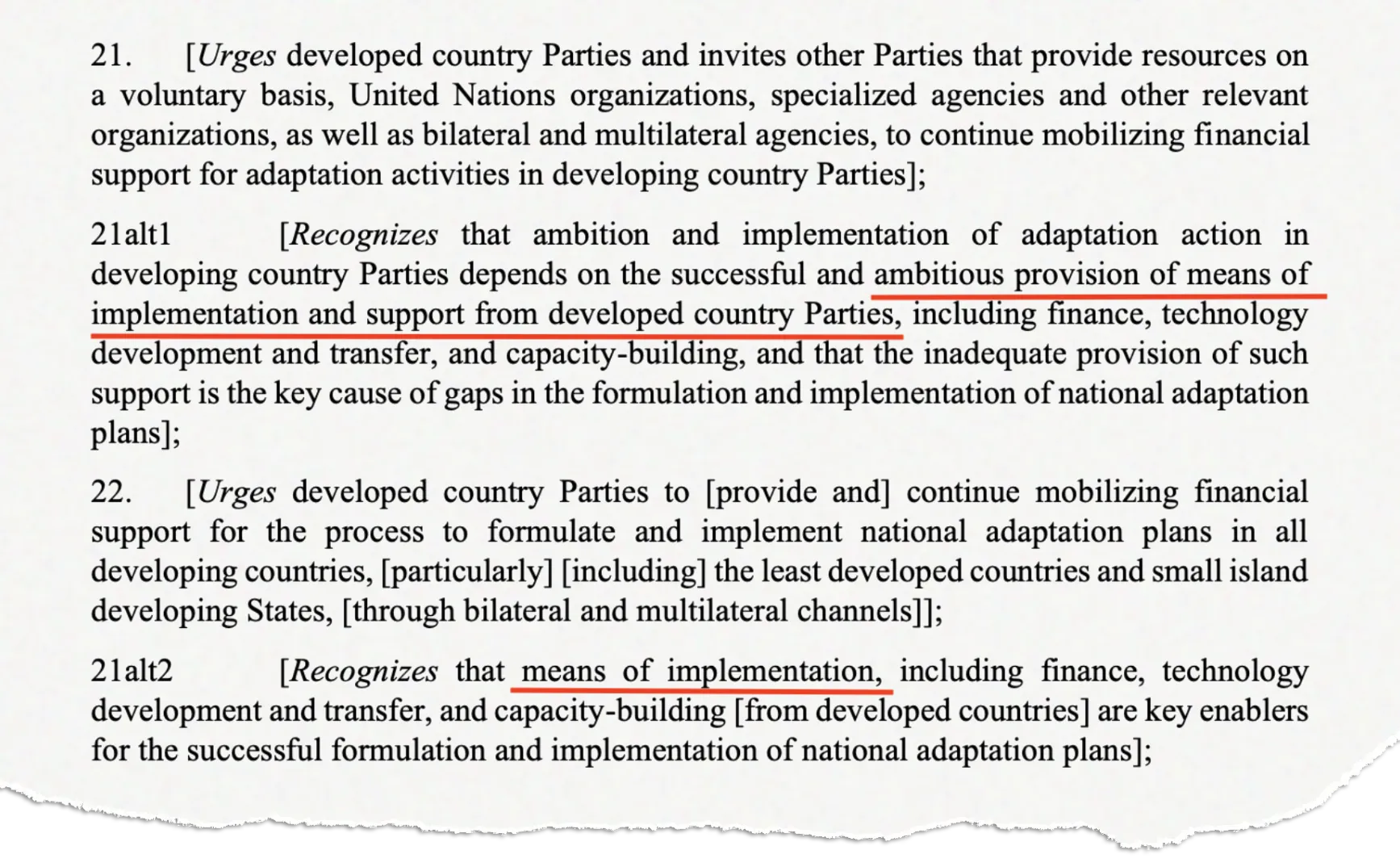

At COP29, despite some progress within negotiations, discussions on national adaptation plans (NAPs) ultimately ended without agreement and were pushed to Bonn.

Talks got underway with the co-facilitators inviting views on the final draft negotiating text from the talks in Baku.

However, discussions quickly ground to a halt when the G77 and China asked for the text to be projected onto the board, a move opposed by the EU and the UK.

Jeffrey Qi, policy advisor with IISD’s resilience program, told Carbon Brief, the text that came out of Baku was “unmanageable”. The first few sessions were therefore dominated by debates as to how to get the text to a position that could truly be negotiated. Qi explained:

“The text from Baku is so unstructured. So I guess the question is, do you open it up for line-by-line negotiation? Like, do you go into drafting mode right away, or do you take general reflections on specific paragraphs?”

The Baku text included 159 brackets and 18 options, highlighting the lack of clarity within it.

After a huddle, the G77 and China submitted a conference room paper (CRP), based closely on the Baku text, but clustered into sections under different headings, according to TWN.

The EU requested additional time to engage with the CRP before proceeding to substantive decisions, but on 21 June, parties returned to negotiations using this new text as the basis.

However, “stark differences” quickly appeared between developed and developing countries, according to TWN.

The ECO newsletter of 23 June called for further action on the NAPs, stating:

“Can someone shake the National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) negotiations out of its slumber?…No more excuses for delaying the much-needed support from developed countries for the formulation and implementation of NAPs in developing countries. Any NAPs decision text not backed by accessible public finance will remain without substance.”

Further informal consultations took place on 24 June and on 25 June, a draft negotiation text was published. However, it was riddled with brackets.

Issues around the inclusion of MoI remained in the text, in particular its role as a key enabler of adaptation.

Ultimately, no further agreement could be reached and Bonn ended without draft conclusions for NAPs.

Qi told Carbon Brief that this was a “disappointing” outcome. He said:

“I think it’s quite disappointing that we are leaving Bonn with essentially the same messy, unbalanced draft texts from Baku. Both developing and developed countries have shared legitimate concerns over the MoI section in the texts and the only way forward is to seek common ground and make a compromise on both sides, so we could move on to the many other substantive elements in the NAP assessment, like gender responsive approaches and adaptation mainstreaming.

Qi added that he expected “the same jujitsu over the texts in Belém”.

Other adaptation negotiations

There were numerous other adaptation-focused negotiation tracks at Bonn, after a series of matters had been pushed from COP29. These included discussions on the adaptation fund, the adaptation committee and adaptation communications.

Discussions took place on numerous elements of the adaptation fund, with parties focusing on the fund’s board membership, its fifth review and arrangements for it to exclusively serve the Paris Agreement, according to ENB.

Ultimately, it was only procedural conclusions that could be agreed upon by parties.

During negotiations on adaptation communications, parties discussed the need for further support for developing countries, the limitations of drafting a universal template for adaptation communications and the need for further training courses, according to ENB.

Numerous texts were produced over the two weeks of intersessionals, with the main takeaway being the need to extend the deadline for parties to make submissions to help inform a synthesis report on adaptation communications.

Draft conclusions on the matter with an invitation for parties to submit further views, but with no firm timelines for this to happen.

On the review of the adaptation committee, disagreements centre on complicated issues of governance relating to whether it serves the Paris Agreement or the overarching UN climate convention.

Ultimately, negotiators could only agree an informal note stating that the issue will be postponed.

There was minimal disagreement over the Nairobi work programme and draft conclusions were published on 23 June. Their main focus was recognition of the importance of the work programme and a call for strengthened collaboration with “diverse knowledge holders”, amongst other points

Finally, negotiations took place on matters related to Least Developed Countries (LDCs) within the adaptation workstream, with parties focusing on a report prepared by the LDC Expert Group (LEG).

The LDCs expressed “profound disappointment” about the barriers they still face to adaptation finance, in particular for NAPs, noting that the lack of resources is “not just frustrating but demoralising”, according to ENB.

Draft conclusions published on the penultimate day of SB62 mostly recognised the findings within the LEG report and invited continued work.

Climate finance

At COP29 last year, nations agreed on a landmark target of at least $300bn a year in “climate finance” by 2035, coming primarily from developed countries.

This money is meant to help developing countries curb their emissions and prepare for worsening climate hazards.

There was broad agreement among global-south nations and NGOs that the $300bn “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) was insufficient to address these challenges.

This is nothing new. Climate finance is a highly contested issue in UN climate talks and developing countries have long argued that they need far more help to take climate action.

Yet the SB talks in Bonn took place against a particularly negative backdrop.

The US, previously one of the biggest contributors, has cancelled virtually all of its climate aid. Major European donors, including Germany, France and the UK, have also announced aid cuts, meaning less support for climate projects overseas.

Negotiators in Bonn were keenly aware of this context. The talks saw developing-country diplomats remind developed countries of their obligations to provide this climate finance, while developed countries highlighted alternative ways to raise money.

As is often the case, finance was a pivotal issue in many of the negotiating strands, from the global stocktake to adaptation. However, there was little time carved out to focus solely on the topic, with just two formally mandated “workshops”.

One of these events gave delegates opportunities to discuss their understanding of Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, which focuses on “making finance flows consistent” with emissions cuts and climate-resilience.

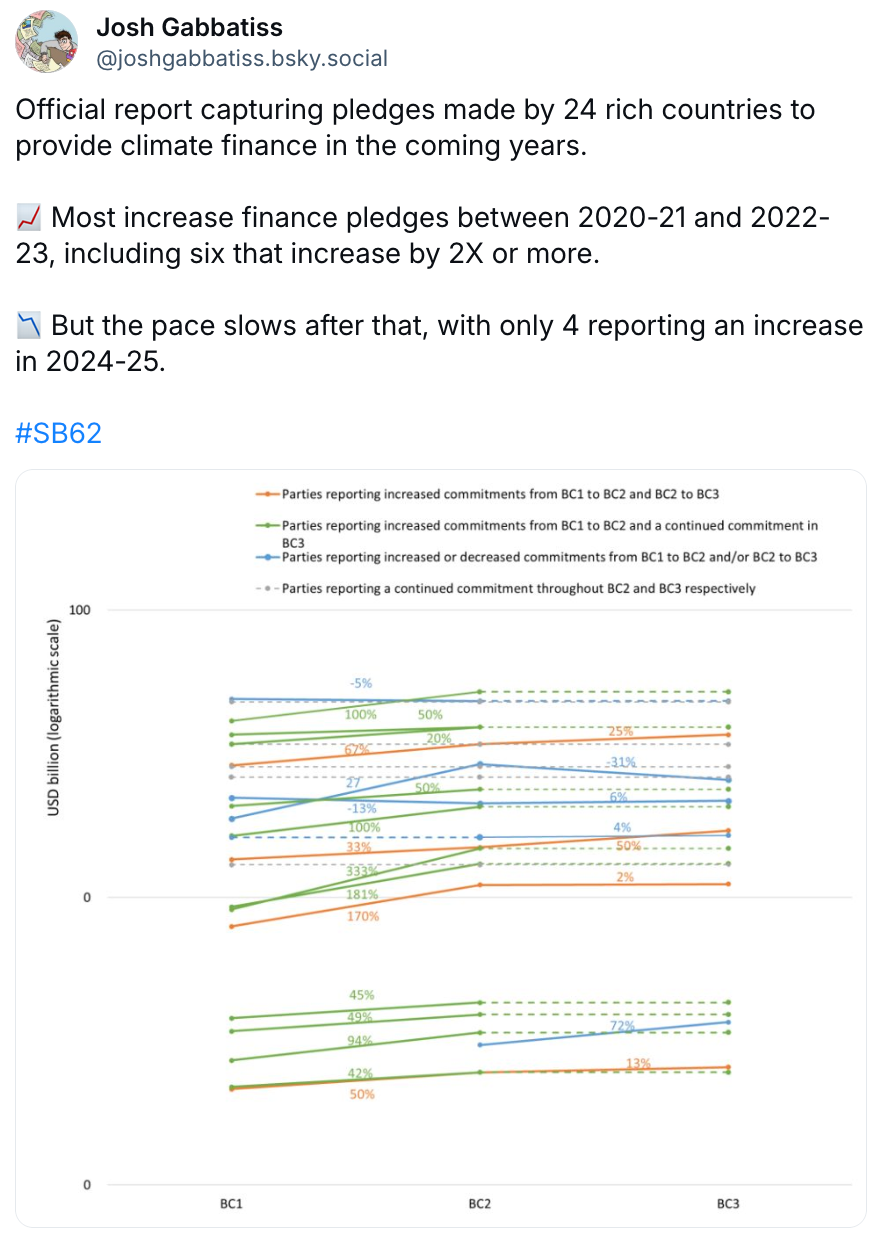

The other workshop allowed parties to discuss the information provided by developed countries in their “biennial communications” of climate-finance pledges, including a new report capturing these commitments.

The most contentious climate-finance discussions took place beyond these mandated events, with the topic at the centre of the “agenda fight” that delayed talks by two days (See: “Future of the process”).

The LMDCs, with support from other developing countries, proposed a new agenda item specifically focusing on the “implementation of Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement” two weeks ahead of the Bonn meeting.

Article 9.1 says developed countries “shall provide” finance to developing countries. This is often interpreted as a legal obligation to provide public, grant-based funding rather than loans or private investments.

Only a fraction of climate finance is currently distributed in this way, but developing countries argue that hundreds of billions of dollars per year should come from such sources.

Developed countries in Bonn pushed back against the proposal, arguing for a broader focus that included contributions from wealthy developing countries and a wider range of sources.

In the end, the new agenda item was dropped, with a compromise of “substantive consultations” on Article 9.1, which would be led by the SB chairs and, ultimately, feed into COP30.

These consultations involved “fiery” exchanges, with developing countries highlighting – among other things – a need for developed countries to triple adaptation finance and provide loss-and-damage finance with public money (See: Loss and damage and Adaptation).

The LMDCs described Article 9.1 as the “weakest link” in finance talks and accused developed countries of “diluting” it across all relevant agenda items.

Notably, the influential group led various middle-income nations in calling for a “work programme” on the topic. They said this could focus partly on overcoming barriers that prevent developed countries from scaling up public finance.

Developed countries argued that they were not averse to providing such funds. Outi Honkatukia, lead EU climate-finance negotiator, told a side event attended by Carbon Brief:

“We’ve heard so much about the 9.1 here over the week-and-a-half so far. I just want to assure [you] that in terms of going forward and priorities for the EU, we honour and abide by our legal commitments on 9.1.”

From the EU’s perspective, Honkatukia said provision of public finance is an “essential part” of the $300bn goal. However, the bloc – and other developed-country parties – also argued for a broader focus that included the “mobilisation” of funds from private finance.

A counter-proposal in the Article 9.1 discussion was made by the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), fronted by Switzerland, with support from several other developed countries.

It involved a new package of three agenda items, with one that covered the whole of Article 9, including parts relating to mobilisation from private sources and other providers. The group suggested this could replace almost all other existing finance agenda items.

Meena Raman, head of programmes of the Third World Network (TWN) – which is closely aligned with the LMDCs – told Carbon Brief the idea was opposed by South Africa and Saudi Arabia. She said the expansion of focus echoed a compromise seen in COP29 NCQG talks:

“[Developed countries] didn’t want 9.1, so the compromise was an Article 9 reference, but, having followed the negotiations, they were very clear this is about mobilisation.”

Both the LMDCs and LMDC member India had already stated plainly in the opening plenary that they intended to continue pushing this issue. The group’s Bolivian spokesperson, Diego Pacheco, told delegates:

“We have been denied this starting point, but rest assured the LMDCs will [go] back to these items at COP30.”

Perhaps the most high-profile finance-related events in Bonn were two consultations on the Baku to Belém roadmap to $1.3tn.

Besides the core $300bn target that emerged from COP29, there was a looser, aspirational call for “all actors” to scale up climate funds to “at least $1.3tn” by 2035.

This reflected the demands of developing countries, based on various needs assessments, for trillions of dollars to meet their climate targets. However, unlike the $300bn – which is expected to mainly come from developed countries – this NCQG element is vague, with the possibility of “all public and private sources” contributing.

The Baku to Belém roadmap was launched in a bid to appease those who were unhappy with the NCQG outcome. It will draw on nations and civil society groups communicating their views on how climate finance can and should be scaled up to reach the $1.3tn target.

The process is coordinated by the Azerbaijani and Brazilian COP presidencies, which will work together to produce a final roadmap document by the end of October.

Going into Bonn, 116 submissions, including 18 from countries or country groups, had been filed, laying out a variety of views on this matter. The SB62 consultations saw a similar diversity of views being offered up, albeit with nations sticking to long-held positions.

For example, the G77 and China argued that the burden of climate finance provision should not be shifted onto developing countries, while the EU encouraged “all with the capacity to do so” to contribute climate finance – implying there ought to be inputs from wealthier developing nations.

The consultations also saw some discussion of the “circle of finance ministers” organised by Brazil, which is also expected to feed into the roadmap discussions.

Ultimately, the roadmap is not yet a formal part of the negotiations. Given this, observers noted that its impact will depend on how it is integrated into the COP30 process in Belém.

When asked about what Brazil’s expectations are for the roadmap report, COP30 executive director Ana Toni told Carbon Brief:

“It’s up to the parties…Many decisions related to finance are not taken by the UNFCCC, like the reform of the multilateral banks is nothing that can be decided here. So, it depends on what comes in the report. Some things, perhaps, will be talking to the negotiation – I would imagine that most to mobilise the $1.3tn won’t.”

Just transition

In Baku in 2024, there was consistent frustration with the management of the just transition work programme (JTWP), which ultimately ended without agreement.

Coming into Bonn, however, the Brazilian presidency made the matter one of its three priorities for COP30, alongside the GGA and implementing the first global stocktake.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Anabella Rosemberg, senior advisor on just transition at NGO umbrella group CAN International, welcomed the priority given to the work programme by the presidency and the secretariat, including “silly things” such as longer time slots for negotiation and a good room during the intersessionals. She added:

“It’s showing that this is being prioritised and that helps. We are not anymore the sort of black sheep at the end, negotiating at 9pm when no one is paying attention, which is where we were last year. So…I’m optimistic, because I feel like the soil is a bit more fertile.”

Additionally, the JTWP ended up absorbing discussions on “unilateral trade measures”, which had been part of the agenda fight at the start of the meeting.

Within the negotiations, old divides quickly emerged between global-north parties that wanted a focus on a workers’ transition and global-south parties that wanted the JTWP to be more holistic, observers told Carbon Brief.

Areas of disagreement included the language around the how to reflect means of implementation (MoI), trade measures, 1.5C pathways, human rights and Indigenous Peoples in the JTWP process, noted the ENB newsletter.

Antonio Hill, advisor at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) told Carbon Brief that overall, negotiations on the JTWP had been more “amenable” than other tracks, adding:

“But I think it’s also true that right throughout, the finance issue keeps cropping up, left, right and centre., And so it’s clear that, as usual, even if things kind of were looking decent, things could get held up because of bigger forces.”

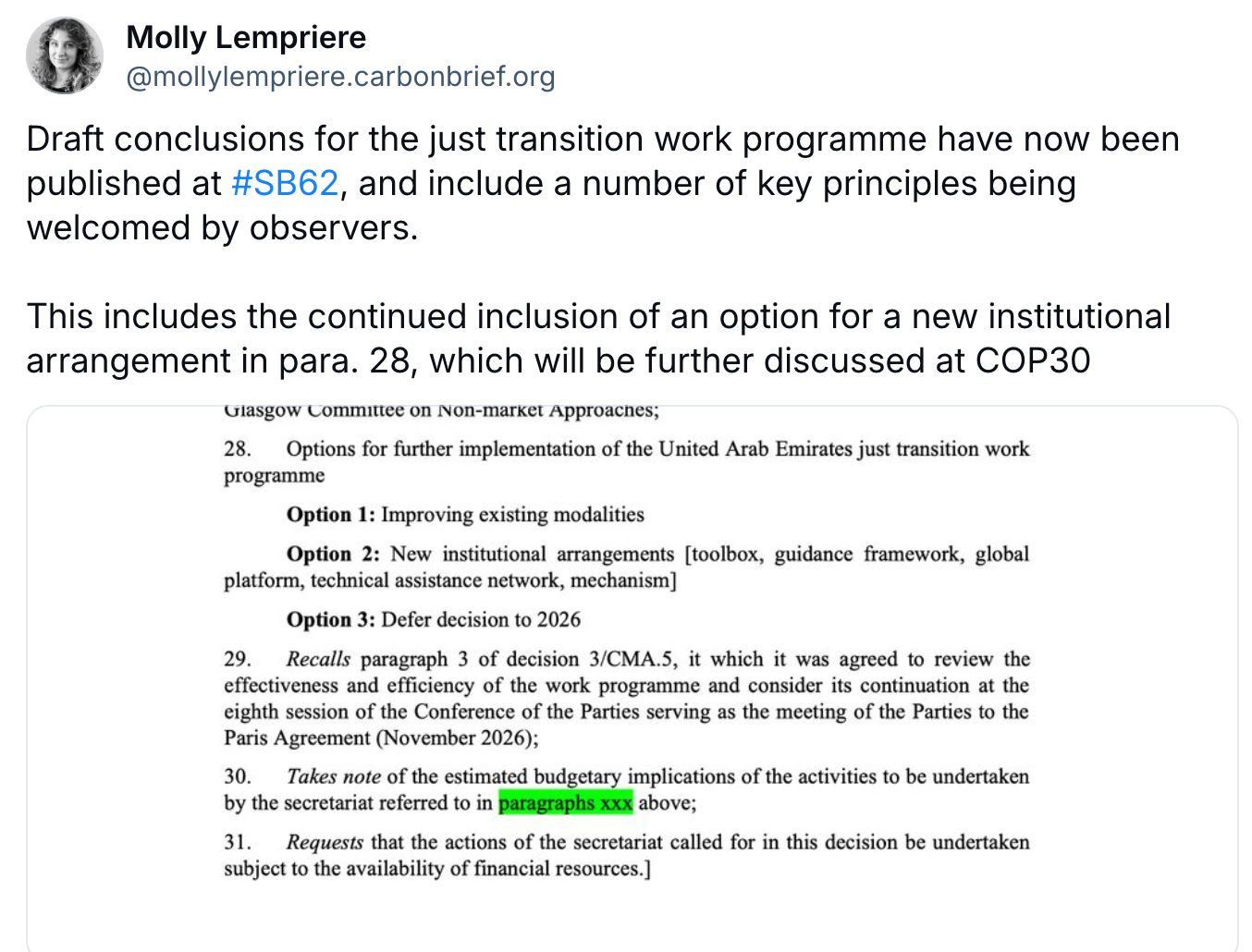

Additionally, there were ongoing debates about the next steps for the JTWP, which is set to come to an end in November 2026.

Parties, including the UK, said it was “premature” to be discussing the next steps, wishing to focus instead on the knowledge sharing dialogues that take place within the JTWP, Dr Leon Sealey-Huggins, a senior campaigner at the charity War on Want told Carbon Brief.

The issue of whether and how to continue the JTWP beyond 2026 was the only significant disagreement remaining, in an informal note published on 23 June.

This included options for a new institutional arrangement, which could set up a mechanism to follow on from the current work programme.

The inclusion of an option for an institutional arrangement is a “big win” for civil society groups, Rosemberg told Carbon Brief.

Similarly, the ECO newsletter also welcomed this option, writing that “the establishment of the Belém Action Mechanism for Just Transition would allow for holistic just transition pathways across the whole economy, covering contexts both within and between countries”.

There were additional points welcomed by civil society groups and parties in the text of the informal note, as Rosemberg told Carbon Brief.

“The idea that a just transition needs to be added in climate plans, it’s the first time that this is stated a bit more formally, directly and with the principles [outlined in the text] in mind. So there is a bit more flesh to how they are brought to the NDC. The idea that climate finance needs to also be made available for covering some of the social justice aspects of the transition, that’s also a very positive message.

However, he acknowledged that the text was far from final agreement, saying “we have to try to keep [these positive elements] for as long as possible”.

Following on from this, a subsequent informal note was published on 25 June, which was nearly identical to the previous version.

The only significant change was the inclusion of options under paragraph 25 on recognising the impact on trade.

The informal note was broadly welcomed, reported ENB. It said that parties, including the UK, AOSIS, the EIG, LDCs, the EU, the Philippines and others, wanted the text to be sent on to COP30 without further changes.

The text was ultimately passed to Belém for further negotiations, despite calls from the LMDCs and the Arab Group to include alternatives to a paragraph on clean energy, an objection from Paraguay to language on gender-based approaches, as well as a Russian call for a reference to unilateral trade measures.

Dr Sealey-Huggins told Carbon Brief that the text was a “good basis” for negotiations in Brazil that could provide an “anchor for our movements on the outside”.

Loss and damage

For years, small islands and other at-risk states fought to raise the status of “loss and damage” at UN talks, securing a new fund in 2023 to support those struck by climate disasters.

Yet, as it stands, the fund has only received $768m in pledges from primarily developed countries, of which just $339m has actually been paid. This is less than 0.2% of developing countries’ estimated needs in a single year.

There was disappointment among climate-vulnerable nations at COP29 when talks failed to produce a new finance target that centres loss and damage.

However, Raju Pandit Chhetri, a climate-finance expert who works with the LDCs, told Carbon Brief in Bonn that “it’s our understanding that the NCQG decision also includes loss and damage”.

He said that while the agreement does not include a specific sub-goal, as hoped, broader references to “climate action” and the “evolving needs” of developing countries encompassed the need for loss-and-damage finance.

Developing countries, therefore, continue to push for a loss and damage focus in finance talks, including consultations on the Baku to Belém roadmap to $1.3tn. (See: Climate Finance.)

Beyond the fund, there is a broader UN loss-and-damage architecture that requires countries’ attention at climate negotiations. This can also provide opportunities for developing countries to push for more loss-and-damage finance.

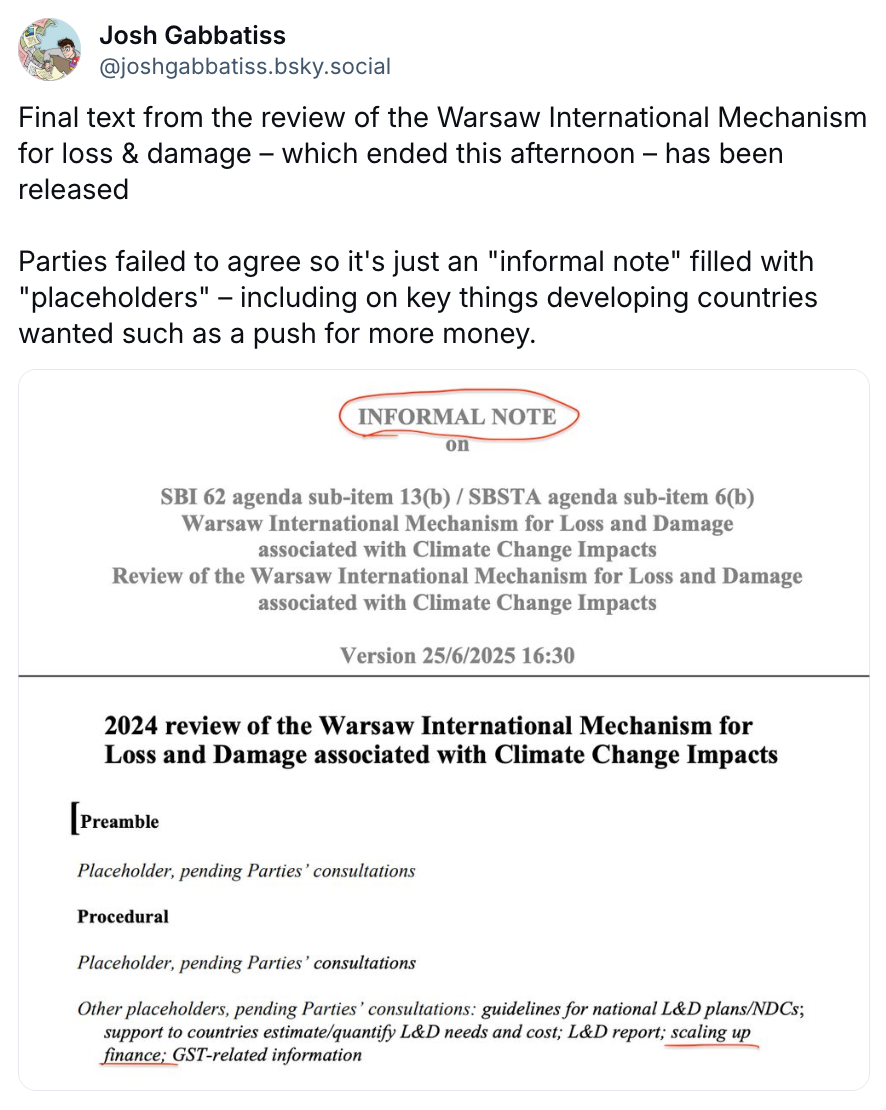

One key component is the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for loss and damage, a work programme that has a goal – among other things – of “enhancing action and support, including finance”.

At COP29, parties were meant to finish discussing a review of the WIM, which takes place every five years. They were also meant to finalise a joint annual report of the WIM executive committee (ExCom) and the Santiago network, another component that is meant to help countries in need gain technical assistance.

Nations failed to reach a conclusion on either of these issues in Baku. Both were simply pushed onto the agenda for the talks in Bonn.

Progress there was limited, despite many hours spent in closed-door discussions.

Negotiators settled on “draft conclusions” for the joint annual report, which will be passed on to COP30. But as the talks reached their final stages, they had failed to agree on a WIM review text.

In the end, an emergency half-hour session was convened on the penultimate day of SB62 that saw negotiators agree to forward an “informal note” to COP30. While the text is less official and full of brackets – indicating areas of indecision – this meant their work had not been wasted.

Hafij Khan, a co-chair of the WIM Executive Committee (ExCom) from Bangladesh, told Carbon Brief:

“We made some progress, even though there is no conclusion – but all the views of the different parties are captured here with bracket, bracket, bracket.”

“Placeholders” in the final text indicate some of the more contentious discussion points, including “scaling up finance”. Text added to the final note, lifted from the NCQG itself, mentions “significant gaps” in loss-and-damage finance and the need to fill them.

Broadly, observers told Carbon Brief that developed countries felt the WIM review was not the venue in which to discuss loss-and-damage finance. Developing countries noted that this is one of the WIM’s functions.

Another function that developing countries wanted to see included in the WIM review was a mandate to launch a global, scientific assessment of loss and damage.

Speaking at a side event in the first week, Vicente Paolo Yu, who leads on loss and damage for the G77 and China, explained that this was one of the group’s priorities. He said that this did not mean nations were unhappy with similar reports produced by NGOs and insurers:

“What we are saying is that many of these kinds of global assessments of disaster risk or whatever are produced by these organisations based on their institutional perspectives.”

Observers have noted that such a report, under the WIM, could be used to map out the scale of the problem and gaps – including finance gaps – in countries’ responses.

Other items left undecided included guidance on the creation of national loss-and-damage plans and discussing the cost-effectiveness of the Santiago network.

These items will continue to be debated when negotiators reconvene at COP30.

Mitigation

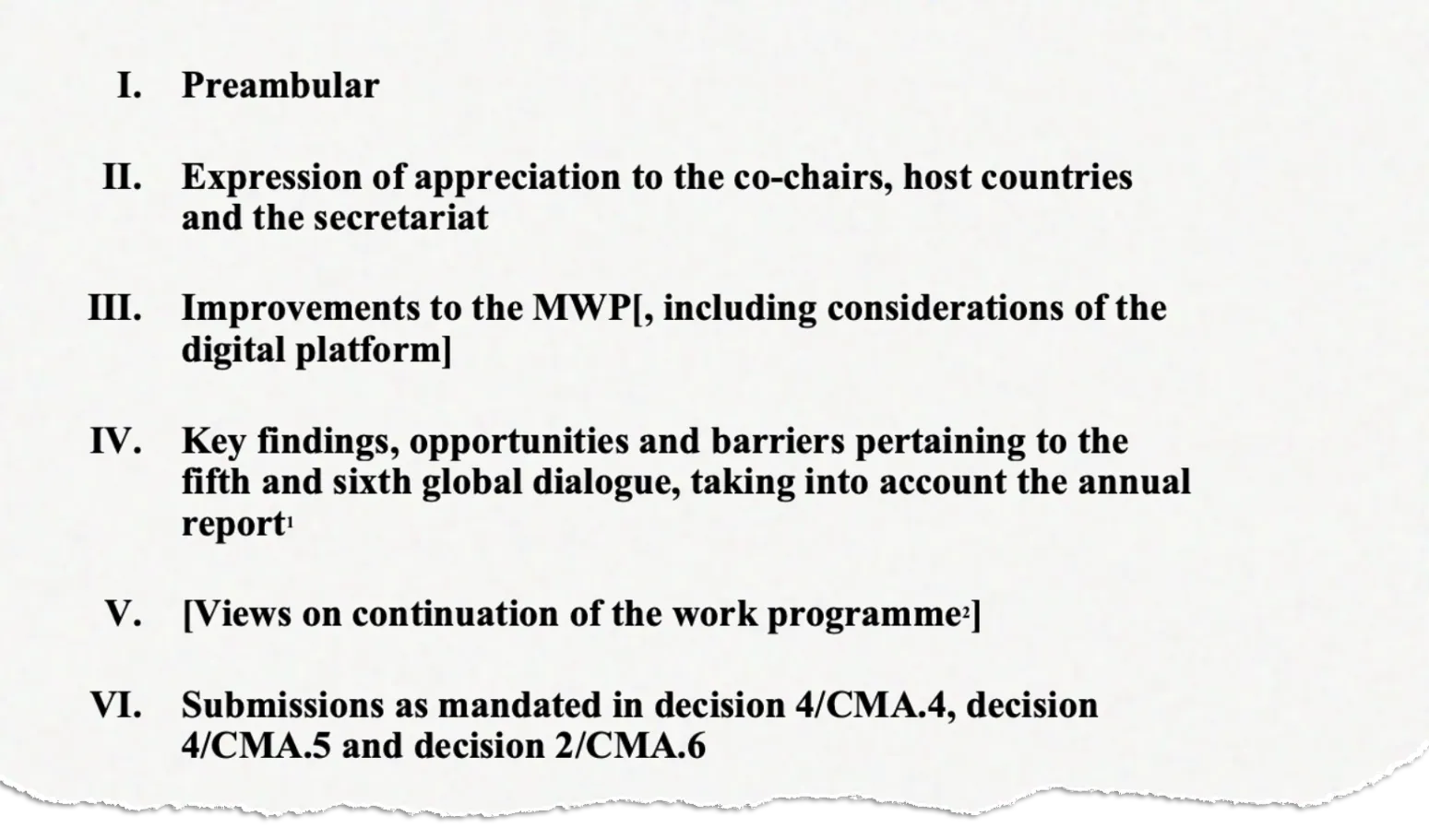

Over the two weeks of Bonn, negotiations took place within the “mitigation work programme” (MWP) over how to ensure it was a “safe space” and on the development of a digital platform.

Consultations began with “heated” discussions on 18 June, according to ENB.

This included AOSIS arguing that the programme was not delivering on its mandate to scale up mitigation ambition and implementation, while AILAC “lamented” the lack of substantial outcomes from the first five dialogues under the MWP, according to ENB.

As part of the discussions on how to ensure that the MWP offers “safe space for overcoming barriers and tak[ing] actionable solutions”, parties including LMDCs, African Group, Arab Group, India, China and others noted that it would remain a safe space as long as its mandate was respected, according to TWN.

As discussions on the MWP moved into their second day, the programme’s purpose and function were called into question. Some want it to remain a space for sharing knowledge, while others want a clearer focus on accelerating action.

One observer told ENB that there was growing frustration as the MWP became “toothless and deadlocked”.

Teppo Säkkinen, advisor on climate, energy and industries at the Finland Chamber of Commerce, told Carbon Brief:

“The main problem in the dynamic with the MWP has stayed the same: for the EU and others with high ambition, it was supposed to be the place to drive the mitigation work; on the other side, some feel that any language on the content of mitigation is prescriptive and top-down.”

Discussions moved onto the establishment of a digital platform and took a “strange turn toward the architecture of IT-infrastructure”, noted ECO.

AOSIS and AILAC cautioned that this should not divert focus from the MWP’s core purpose of scaling up mitigation ambition, noted ENB, a thought shared by wider observers.

Lola Vallejo, diplomacy and partnerships director at the European Climate Foundation (which funds Carbon Brief) and former co-chair of the MWP said that much of the disagreement is on whether the development of a digital platform truly falls under its mandate. She told Carbon Brief:

“There’s disagreement because the idea [of developing a digital platform] didn’t convince everyone – somehow surprisingly maybe some developed countries could give it a try, but others are dead against it on the basis that i) the UNFCCC wasn’t set up for this and doesn’t have the capacity for matchmaking projects to financiers and it’d be veering too far from its skillset ii) see it as a distraction that would scupper the MWP’s ability to be the only space to tackle mitigation head-on.”

Disagreements around what exactly this digital platform would consist of stalled negotiations in the second week.

Informal notes published during the second week mostly consisted of placeholders, outlining the structure of conclusions to be adopted at COP30, with minimal substantive contents. They also made clear that parties disagreed on whether the MWP should continue.

Despite the brevity of the second note, the text is still welcome, Vallejo told Carbon Brief:

“Bonn is about preparing the text of the decisions adopted at COP. Even if ‘just’ headlines are adopted, it’s progress. And no one would expect full decisions to be adopted during SBs.”

As negotiations on the final day of Bonn got underway, the MWP remained one of the streams without draft conclusions.

A final informal note was produced at 2pm, but there was little that was different to the previous version, beyond an additional reference to “global dialogues” and “investment-focused events”.

Fernanda de Carvalho, head of policy for climate and energy at WWF International, told Carbon Brief that it was “unfortunate that after three years, the MWP is far from delivering its mandate of scaling up mitigation ambition and implementation this decade”. She added:

“While developed countries are correctly pushing for mitigation outcomes, we can’t see a single funded partnership on any of the global dialogues’ themes coming out of the MWP, which could build trust among significantly diverging views. Other countries are doing their best to avoid the mitigation work programme to discuss…mitigation, with GST and NDCs becoming forbidden acronyms.”

On the virtual platform, de Carvalho said that it “started as a good idea” but “got trapped in a very visible delaying tactic”. She concluded that despite these challenges, civil society groups “still believe this track can become a ‘safe space’ in Brazil, as part of a political response to the ambition gap”.

Global stocktake and climate pledges

COP30 is taking place in a key year for the international climate regime.

Under the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet” mechanism, countries must submit more ambitious plans for cutting emissions every five years.

In 2025, they are due to offer pledges covering the years, ideally bringing the world on track for the Paris Agreement temperature target.

However, nearly every nation missed the first UN deadline to come forward with a new, more ambitious climate plan or “nationally determined contribution” (NDC).

NDCs are expected to trickle in over the coming months in time for the extended September deadline, setting the tone for COP30 talks.

In the meantime, the Brazilian presidency has highlighted the work triggered by the global stocktake (GST) back in 2023 as a priority, describing it as a “blueprint to course correct on the climate trajectory towards a 1.5C-aligned future”

It says the GST, with its pledges to triple global renewable energy capacity and “transition away” from fossil fuels, should function as a “global NDC”:

“Using the GST as a reference, we will be able to transform climate action from cacophony into an orchestrated symphony – where multilateral negotiations set the score, and NDCs and the action agenda provide the instruments.”

In practice, the GST has proved highly contentious since it was agreed at COP28. GST negotiations continued across three agenda items at the climate talks in Bonn, after they failed to reach a substantial outcome at COP29 last year in Baku.

The stocktake continued to stoke division in Bonn, particularly in discussions on the United Arab Emirates (UAE) dialogue on “implementing GST outcomes”. As talks drew to a close, Alden Meyer from E3G told Carbon Brief:

“There is a fundamental divide in the room on what the purpose of these dialogues should be and what the outcomes should be.”

Broadly speaking, developed countries, small-island states, LDCs and the Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) want to see more focus on some of the “mitigation” outcomes from the GST, including the transition away from fossil fuels.

Some developing countries – particularly the LMDCs – would rather the dialogue focus exclusively on finance. They argue that, because the paragraph establishing the UAE dialogue was under a subheading for “finance” in the GST text, this should be the only focus.

As negotiations dragged on, it became clear by the final day that parties were simply not going to reach any kind of common ground.

The final text to emerge was simply two documents – separate iterations that negotiators had been considering – combined together, with no attempt to seek consensus.

There is no direct reference to “transitioning away” from fossil fuels, but an allusion survives in one of the iterations.

In bracketed text, meaning it has not been agreed, the document makes a reference to “decid[ing] that the UAE dialogue will…consider collective progress and identify opportunities for implementing the elements that do not have an institutional home, including collective calls on energy transition”.

The document states clearly at the top that it “includes divergent views, has not been agreed upon, does not reflect consensus, is not exhaustive, has no formal status and is open to revision”.

Both texts within the document contain many brackets and “options”, indicating even more areas of divergence that will need to be addressed before COP30.

Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, told Carbon Brief that parties had not “given up” on fossil-fuel language, adding “we heard many bringing it up in the rooms”. Abreu said:

“The vast majority of countries remain committed to what was agreed at COP28…But we’ve seen an active attempt from a tiny number of parties to unravel the agreement in the last couple of years, across multilateral spaces not just the UNFCCC – and the same tactics were on full display in Bonn.”

However, Abreu noted that for many countries, a deal on this topic was “contingent” on progress in other areas, particularly on finance and adaptation.

Road to COP30

With Bonn coming to a close, attention is turning to COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November.

Once again, discussion around the host country’s oil and gas industry has drawn criticism from observers and environmental campaigners.

In June, Brazil’s oil sector regulator, ANP, announced that the country would auction the exploration rights for 172 oil and gas blocks spanning 56,000 square miles, mostly offshore.

Despite opposition from environmental campaigners and Indigenous communities, the auction is still set to go ahead, just months before the country hosts the climate summit.

Throughout the Bonn intersessionals, the challenges of finding accommodation in Belém were highlighted in a number of forums. Over recent months, there have been reports of people paying more than $15,000 for a hotel room and more than $400,000 for an apartment, for the two weeks of the summit.

After the Brazilian presidency attempted to alleviate concerns by suggesting delegates could dock boats near the venue, one observer joked to ENB, “now I just need to get my yacht to Brazil”.

Beyond logistics, civil society groups have been setting out their hopes for the Brazilian presidency’s focus areas of measuring adaptation, just transition and the stocktake.

But the underlying issue of finance remains “unresolved”, meaning “we have only seen baby steps when what we need is a giant leap”, said Cosima Cassel, programme lead on climate diplomacy and geopolitics at thinktank E3G, in a statement. She added:

“COP30 must mark a decisive step change in delivery. Brazil has shown energy and creativity in shaping its presidency vision, but this alone is not enough. In the coming months, it must get specific and transparent about what the COP30 package – both negotiated and non-negotiated – will include.”

Cassel said this package would need to “credibly close the ambition gap” that was likely to remain, even after countries submit their new climate pledges, due by September 2025.

David Waskow, director of the international climate initiative at the World Resources Institute, said in a statement that national leaders “need to start delivering”:

“With the 1.5C window closing fast, every fraction of a degree – and every decision – matters.

Beyond Brazil, there is yet to be a decision as to who will host COP31 in 2026. There are competing bids from Australia, with the Pacific Islands, and Turkey.

In the closing plenary, both reaffirmed their commitment to working with the presidency to resolve this decision – and to upholding multilateralism more broadly.

| 30 June to 3 July 2025 | Fourth finance for development summit, Spain |

| 14-23 July 2023 | High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development |

| 9-29 September 2025 | UN general assembly, New York |

| 10-21 November 2025 | COP30, Belém, Brazil |

| 22-23 November 2025 | G20 summit, South Africa |