Climate change made ‘fire weather’ in Chile and Argentina three times more likely

Multiple Authors

02.11.26Multiple Authors

11.02.2026 | 11:19amThe hot, dry and windy weather preceding the wildfires that tore through Chile and Argentina last month was made around three times more likely due to human-caused climate change.

This is according to a rapid attribution study by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) service.

Devastating wildfires hit multiple parts of South America throughout January.

The fires claimed the lives of 23 people in Chile and displaced thousands of people and destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands in both Chile and Argentina.

The authors find that the hot, dry and windy conditions that drove the “high fire danger” are expected to occur once every five years, but that these conditions would have been “rarer” in a world without climate change.

In today’s climate, rainfall intensity during the “fire season” is around 20-25% lower in the areas covered by the study than it would be in a world without human-caused emissions, the study adds.

Study author Prof Friederike Otto, professor of climate science at Imperial College London, told a press briefing:

“We’re confident in saying that the main driver of this increased fire risk is human-caused warming. These trends are projected to continue in the future as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels.”

‘Significant’ damage

The recent wildfires in Chile and Argentina have been “one of the most significant and damaging events in the region”, the report says.

In the lead-up to the fires, both countries were gripped by intense heatwaves and droughts.

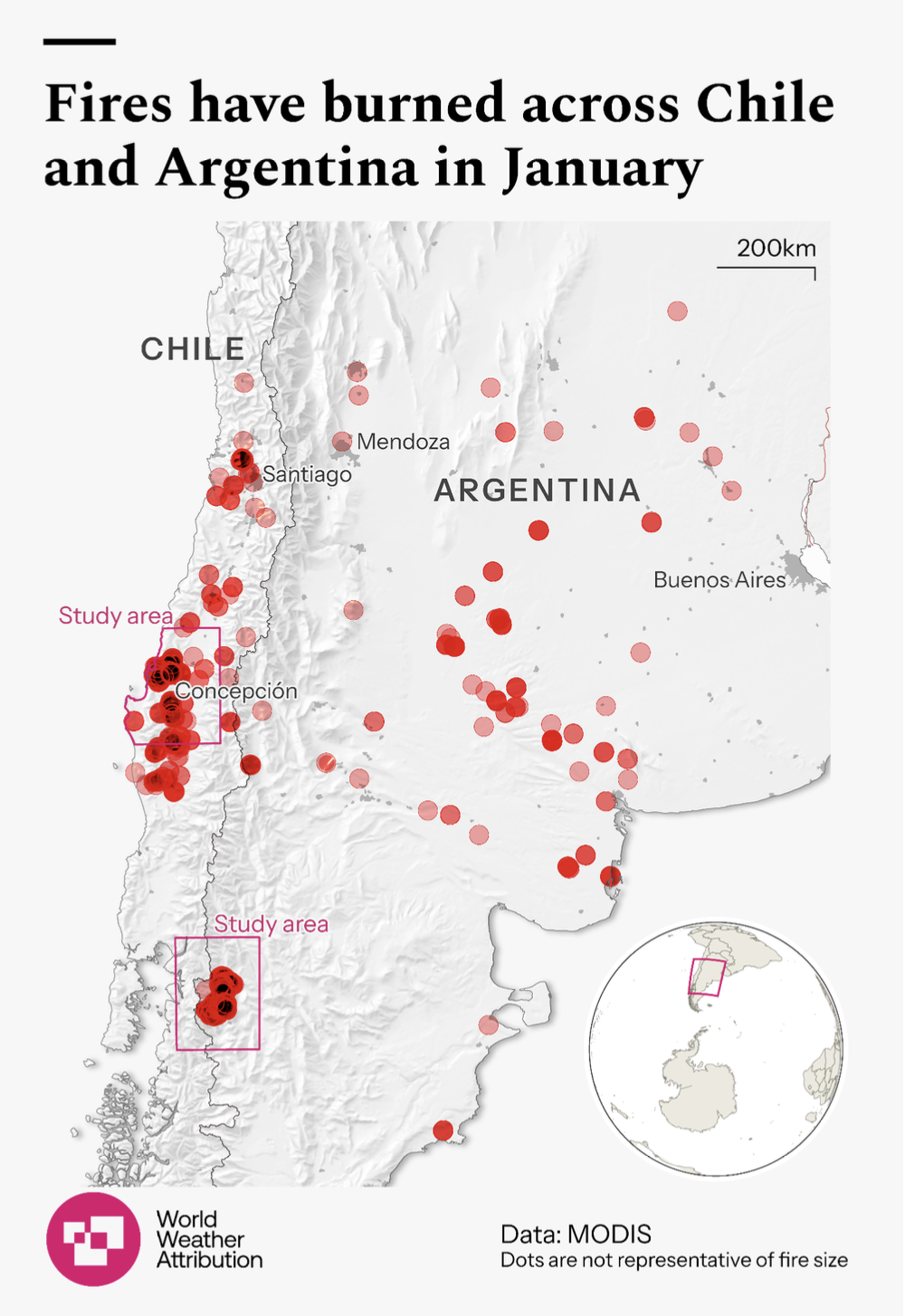

The authors analysed two regions – one in central Chile and the other in Argentine Patagonia, along the border between Argentina and Chile.

For example, in Argentina’s northern Patagonian Andes, the last recorded rainfall was in mid-November of 2025, according to the report. It adds that in early January, the region recorded 11 consecutive days of “extreme maximum temperatures”, marking the “second-longest warm spell in the past 65 years”.

Dr Juan Antonio Rivera, a researcher at the Argentine Institute of Snow Science, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences, told a WWA press briefing that these weather conditions dried out vegetation and decreased soil moisture, which meant that the fires “found abundant fuel to continue over time”.

In the northern Patagonian Andes of Argentina, wildfires started on 6 January in Puerto Patriada and spread over two national parks of Los Alerces and Lago Puelo and nearby regions. These fires remained active into the first week of February.

The fires engulfed more than 45,000 hectares of native and planted forest, shrublands and grasslands, including 75% of native forests in the village of Epuyén, notes the study.

At least 47 homes were burned, according to El País. La Nación reported that many families evacuated themselves to prevent any damage.

In south-central Chile, wildfires occurred from 17 to 19 January, affecting the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

They started near Concepción city, the capital of the Biobío region, where maximum temperatures reached 26C. In the nearby city of Chillán, temperatures reached 37C.

From there, the fires spread southwards to the coastal towns of Penco-Lirquen and Punta Parra, in the Biobío region.

The event left 23 people dead, 52,000 people displaced and more than 1,000 homes destroyed in the country, according to the study.

These wildfires burnt more than 40,000 hectares of forests, “tripling the amount of land burned in 2025” across the country, reported La Tercera.

The study adds that more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including Monterey pine and Eucalyptus trees, were consumed by the blaze and critical infrastructure was affected.

A WWA press release points out that the expansion of non-native pines and invasive species “has created highly flammable landscapes in Chile”.

Hot, dry and windy

Wildfires are complex events that are influenced by a wide range of factors, such as atmospheric moisture, wind speed and fuel availability.

To assess the impact of climate change on wildfires, the authors chose a “fire weather” metric called the “hot dry windy index” (HDWI). This combines maximum temperature, relative humidity and wind speed.

While this metric does not include every component that could contribute to intense wildfires, such as land-use change and fuel load data, study author Dr Claire Barnes from Imperial College London told a press briefing that HDWI is “a very good predictor of short-term, extreme, dry, fire-prone conditions”.

The authors chose to analyse two separate regions. The first lies along the coast and the foothills of the Andes around the Ñuble, Biobío and La Araucanía regions in central Chile. The second sits across the Chilean and Argentine border in Patagonia.

These regions are shown on the map below, where red circles indicate the wildfires recorded in January 2026 and pink boxes represent the study areas.

The authors also selected different time periods for the two study regions, to reflect the “different lengths of peak wildfire activity associated with the fires in each region”.

For the central Chilean study area, the authors focus their analysis on the two most severe days of HDWI, 17-18 January. For the Patagonian region, they focus on the most severe five-day period, which took place over 2-6 January.

To put the wildfire into its historical context, the authors analyse data on temperature, wind and rainfall to assess how HDWI over the two regions has changed since the year 1980.

They find that in both study regions, the high HWDI recorded in January is not “particularly extreme” in today’s climate and would typically be expected roughly once every five years. However, they add that the event would have been “rarer” in a world without climate change, in which average global temperatures are 1.3C cooler.

The authors also use a combination of observations and climate models to carry out an “attribution” analysis, comparing the world as it is today to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change.

They find that climate change made the high HDWI three-times more likely in the central Chilean region and 2.5-times more likely in the Patagonian region.

The authors also conduct analysis focused solely on November-January rainfall.

Both study regions experienced “very low rainfall” in the months leading up to the fires, the authors say. They find that fire-season rainfall intensity is around 25% lower in the central Chilean region and 20% lower in the Patagonia region in today’s climate than it would have been in a world without climate change.

Finally, the authors considered the influence of climatic cycles such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a naturally occurring phenomenon that affects global temperatures and regional weather patterns.

They find that a combination of La Niña – the “cool” phase of ENSO – combined with another natural cycle called the Southern Annular Mode, led to atmospheric circulation patterns that “favoured the hot and dry conditions that enhanced fire persistence and severity in parts of the region”.

However, they add that this has a comparably small effect on the overall intensity of the wildfires, with climate change standing out as the main driver.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Vulnerable communities

The wildfires affected native forests, national parks and small rural and tourist communities in both countries.

A 2025 study conducted in Chile, cited in the WWA analysis, found that 74% of survey respondents did not have appropriate education and awareness on wildfires.

This suggests that insufficient preparedness on early warning signs, response measures and prevention can “exacerbate the severity and frequency of these events”, the WWA authors say.

Aynur Kadihasanoglu, senior urban specialist at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center, said in the WWA press release that many settlements in Chile are close to flammable pine plantations, which “puts lives and livelihoods at risk”.

Additionally, the head of Chile’s National Forest Corporation pointed to “structural shortcomings” in fire prevention, such as lack of regulation in lands without management plans, reported BioBioChile.

In Argentina, the response to the fires has been hampered by large budget cuts and reductions in forest rangers, according to the WWA press release. Experts have criticised Argentina’s self-styled “liberal-libertarian” president Javier Milei for the cuts and the delay to declaring a state of emergency in Patagonia.

According to the Associated Press, “Milei slashed spending on the National Fire Management Service by 80% in 2024 compared to the previous year”. The service “faces another 71% reduction in funds” in its 2026 budget, the newswire adds.

Argentinian native forests and grasslands are experiencing “intense pressure” from wildfires, according to the study. Many vulnerable native animal species, such as the huemul and the pudú, are losing critical habitat, while birds, such as the Patagonian black woodpecker, are losing nesting sites.