EAT-Lancet report: Three key takeaways on climate and diet change

Multiple Authors

10.02.25Multiple Authors

02.10.2025 | 11:30pmA global shift towards “healthier” diets could cut non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane, from agriculture by 15% by 2050, according to a new report.

The EAT-Lancet Commission report on “healthy, sustainable and just food systems” says this diet would require producing more fruit, vegetables and nuts, as well as fewer livestock.

The findings build on the widely cited 2019 report from the EAT-Lancet Commission – a group of leading experts in nutrition, climate, economics, health, social sciences and agriculture from around the world.

The new report notes that one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions come from the global food system.

These emissions are so great that, even if all fossil fuels were phased out, “food can on its own push us beyond the 1.5C limit”, one of the commission co-chairs, Prof Johan Rockström, told a press briefing.

The report details a “planetary health diet” – a concept first introduced in the 2019 report – which focuses on “plant-rich” and “minimally processed” foods.

The latest edition builds on the previous report by adding improved modelling of food-system transformation and adding social-justice considerations.

The 2019 report faced a “massive online backlash” against some of its findings, particularly on cutting meat consumption, DeSmog reported earlier this year, which was “stoked by a PR firm that represents the meat and dairy sector”.

Rockström said the commission is “ready to meet that assault” if it arises again and issued concern “over this return of mis- and disinformation and denialism on climate science”.

Here, Carbon Brief picks out three key takeaways from the latest report.

- A ‘plant-rich’ diet has the best health and climate outcomes

- Transforming food systems could ‘substantially reduce’ the associated emissions

- Social justice should be a ‘central goal’ in transforming global food systems

A ‘plant-rich’ diet has the best health and climate outcomes

The new report recommends a plant-rich “planetary health diet”, which is largely the same as the one first outlined in the 2019 report.

The diet is designed to be flexible and “compatible with many foods, cultures, dietary patterns, traditions and individual preferences”, the report says.

It does not exclude meat or dairy products – the foods that cause the highest emissions – but recommends limited portions, equating to around one glass of milk per day and a couple of servings of meat and two eggs each week, for those whose diets include them.

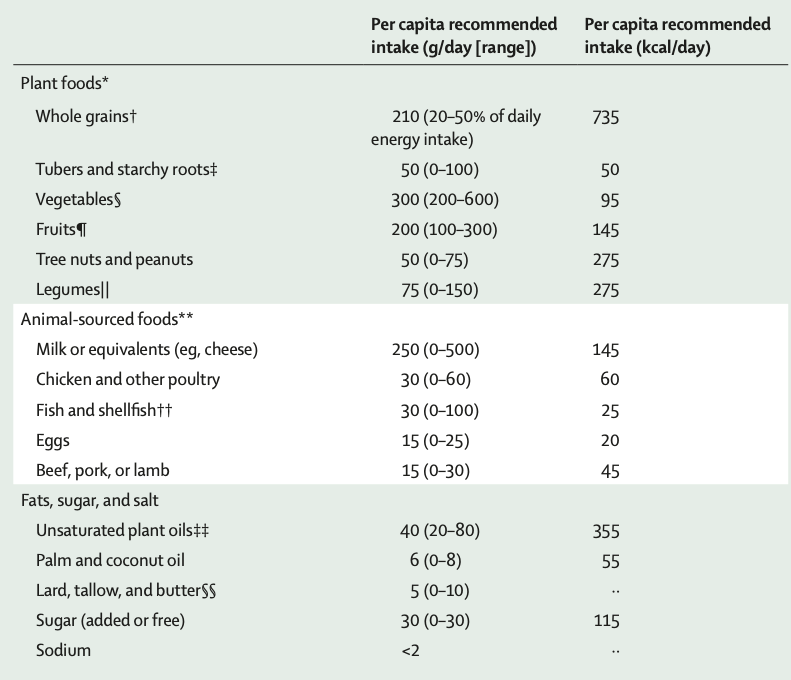

The chart below outlines the recommended intake of different foods, adding up to around 2,400 calories each day. A range is given for each food type to accommodate different diets. The categories with the largest intakes include whole grains, plant oils, nuts and legumes.

The diet is “designed for health…[not] sustainability”, Dr Line Gordon, a commissioner on the report, told a press briefing.

But the report also analyses the climate impact of the recommendations. It estimates that shifting to the planetary diet could reduce global non-CO2 agricultural emissions – from greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide – by 15% by 2050. (See: Transforming food systems could ‘substantially reduce’ the associated emissions.)

Widespread adoption of the diet would require a two-thirds increase in fruit, vegetable and nut production and allow for a one-third reduction in livestock meat production, compared to 2020 levels.

Currently, diets across the globe all “deviate substantially” from the report’s recommendations. But the report claims that, due to the planetary diet’s health benefits, around 15 million “avoidable” deaths could be prevented each year if it were widely adopted.

The report also measures how much global food systems contribute to the nine planetary boundaries – a concept of global thresholds for a “safe and just” planet. It finds that food systems are the largest contributor to five breaches of these boundaries, which include changes in the use of land and freshwater.

In terms of steps to move towards the planetary diet, Gordon listed actions such as changing taxes to make healthy foods more affordable, clearly labelling foods and shifting agricultural production subsidies towards healthier foods.

The report highlights that “transforming food systems is not only possible, it’s essential to securing a safe, just and sustainable future for all”, Rockström says in a statement.

Transforming food systems could ‘substantially reduce’ the associated emissions

Food systems are responsible for about one-third of human-driven greenhouse gas emissions.

These emissions are roughly equally partitioned between livestock and crop production, land-use change and other aspects of the food system, including refrigeration, fertilisers, transport and retail, according to the report.

The authors use global economic models to determine how different actions towards transforming food systems could affect agricultural production, environmental impact and food prices.

For the baseline, they use a set of “business-as-usual” parameters. This scenario uses SSP2-7.0, a high-emissions pathway under which there is a global population of 9.6 billion people and global warming of 2C above pre-industrial temperatures in 2050.

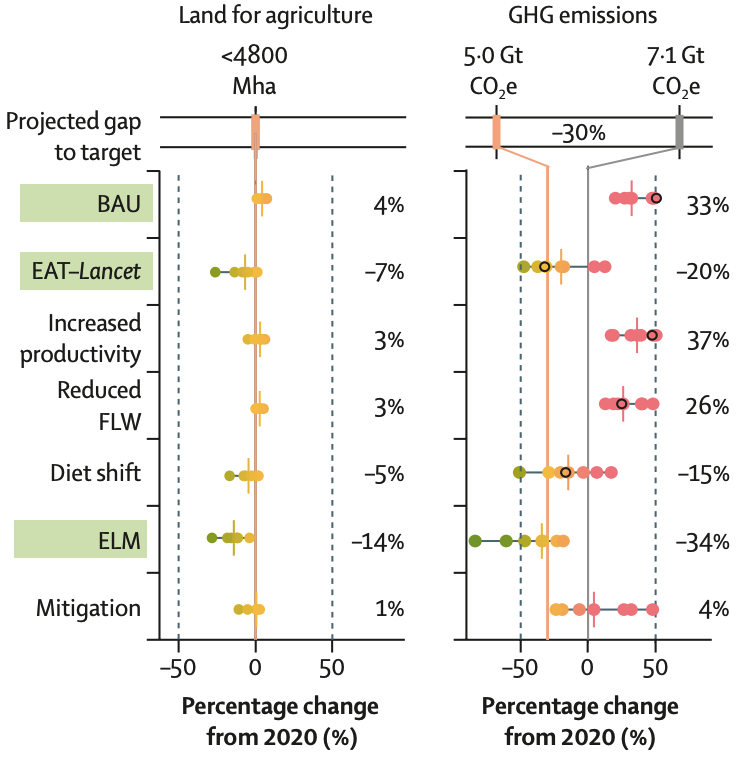

Using these assumptions, the business-as-usual scenario results in a 37% increase in global agricultural production and a 33% rise in non-CO2 agricultural emissions by 2050, compared to 2020. Crop yields increase by nearly one-quarter in this scenario, while the amount of land used for agricultural cultivation expands by 2m square kilometres (km2) – an area roughly the size of Mexico.

The chart below shows the changes in non-CO2 agricultural emissions and agricultural land use under each scenario, with the three main scenarios highlighted in green. The dots indicate the results from different model runs.

The dietary transformation projection assumes a world in which there is total adherence to the suggested diet, a halving of food loss and waste and an additional 7-10% increase in global agricultural productivity.

They find that, in this scenario, agricultural emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases decline by 20% compared to 2020 values. Although cropland will have to expand to account for the increased intake of fruits, vegetables and legumes, the decrease in land needed for livestock-rearing means that agricultural land use will fall overall by 3.4m km2, an area the size of India.

The authors also consider a scenario that combines the dietary shifts with “ambitious mitigation” efforts. This includes policies such as carbon pricing and land-use regulations that could drive the adoption of bioenergy, afforestation and renewable energy, the report says.

Under widespread dietary shifts and ambitious mitigation, the report finds that non-CO2 emissions from agriculture will fall by 34% compared to 2020, and the reduction in agricultural land use will double compared to the scenario that only factors in the dietary shifts.

Social justice should be a ‘central goal’ in transforming global food systems

In a step further than its predecessor, the new report assesses justice in global food systems, by analysing the rights to food, a healthy environment and decent work.

The focus on social equity and justice added a “tremendous broader aspect” to the report, Dr Shakuntala Thilsted, one of the commission co-chairs, said in a briefing.

The report notes that more than half of the world’s population struggles to access healthy diets, which leads to “devastating consequences for public health, social equity and the environment”.

This primarily affects marginalised people living in low-income regions, it says.

The report finds that the diets of the world’s richest 30% of the population contribute to more than 70% of environmental pressures from food systems, such as land use and greenhouse gas emissions. The report says:

“These statistics highlight the large inequalities in the distribution of both benefits and burdens of current food systems.”

Furthermore, living and working in toxic-free environments and stable climate conditions is a “crucial” human right, it adds.

According to the report, “power asymmetries and discriminatory social and political structures” – such as the concentration of power among a small number of agribusiness firms – hinder the fulfilment of those rights.

The report says that social justice, along with environmental sustainability, should be central to global food systems.

It proposes several steps to making healthy, sustainable and just food systems more accessible by 2050: securing decent working conditions, ensuring liveable wages, recognising and protecting marginalised groups and limiting market concentration.

It notes that while taking steps to mitigate climate change will increase food costs – particularly in areas that currently do not consume adequate fruits and vegetables, and where animal-sourced food is less commonly eaten – some of these pressures can be alleviated by introducing subsidies targeted towards those preferred food groups.

Finally, the authors underscore that implementing this diet must consider both cultural context and sustainability.

However, they also warn that meeting these goals requires global action and “transformative change” in both individual and cultural habits.

Rockström, J. et al. (2025). The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable and just food systems, The Lancet Commissions, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01201-2