Factcheck: What the Climate Change Act does – and does not – mean for the UK

Multiple Authors

10.07.25Multiple Authors

07.10.2025 | 2:39pmThe UK’s Climate Change Act is a landmark piece of legislation that guides the nation’s response to global warming and has proved highly influential around the world.

Increasingly, the law has come under attack from right-wing politicians, who want to scrap the UK’s net-zero target and the policies supporting it.

Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch has announced that her party would “repeal” the Climate Change Act entirely, if her party is able to form the next government.

The opposition leader said she still believed that “climate change is real”, but offered no replacement for the legislation that the Conservatives have backed since its inception.

Her proposal drew intense criticism from scientists, business leaders and even senior Conservatives, who argued that abandoning the act would harm the UK economy and drive more climate extremes.

Meanwhile, the hard-right populist Reform UK party – which is currently leading in the polls – has also rejected climate action and promised to “ditch net-zero”.

Below, Carbon Brief explains what the Climate Change Act does – and does not – mean for the UK, correcting inaccurate comments as the UK’s political right veers further away from the previous consensus on climate action.

- Why does the UK have the Climate Change Act?

- What does the Climate Change Act require?

- The costs and benefits of the Climate Change Act

- How nearly 70 countries followed the UK’s Climate Change Act

- What comes next under the Climate Change Act?

- What would happen if the Climate Change Act was repealed?

Why does the UK have the Climate Change Act?

It is well-known that the Climate Change Act was voted through the UK parliament with near-unanimous cross-party support. In October 2008, some 465 MPs voted in favour, including 263 Labour members, 131 Conservatives, 52 Liberal Democrats. Just five Conservatives voted against.

Less widely appreciated is the fact that the Labour government only agreed to legislate in the face of huge public and political pressure, including from then-Conservative leader David Cameron.

Jill Rutter, senior fellow at thinktank the Institute for Government (IfG), tells Carbon Brief that the Conservatives “can also claim significant credit for the Climate Change Act”.

This is at odds with comments made by Badenoch, who described it as “Labour’s law”, when pledging to repeal it if she were ever elected as prime minister.

In early 2005, two Friends of the Earth campaigners – Bryony Worthington and Martyn Williams – had drafted a Climate Change Bill, inspired by the “worsening problem of climate change and the inadequacy of the government’s policy response”, according to a 2018 academic paper.

Worthington tells Carbon Brief they had “decided [the government’s plan] was rubbish and we needed a different approach”, based on five-yearly carbon budgets rather than single-year goals.

Their draft was introduced into parliament that July, as a private members’ bill, by high-profile backbench MPs from the three main political parties: Labour’s Michael Meacher; the Conservatives’ John Gummer (now Lord Deben); and Norman Baker for the Liberal Democrats.

This was the centrepiece of Friends of the Earth’s “Big Ask” campaign, gaining huge public support and backing from more than 100 other NGOs, 412 MPs and celebrities such as Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke.

Then, in December 2005, Cameron was elected Conservative leader, using support for climate action as part of his efforts to “‘decontaminate’ the Tory brand”, according to an IfG retrospective.

With the Labour government still resisting the idea of new climate change legislation, Cameron made what the IfG called a “really significant political intervention” on 1 September 2006, throwing his weight behind the “Big Ask” and publishing his own draft bill, on green recycled paper.

Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

As the Guardian reported at the time, a letter from Cameron and others “call[ed] on the government to enshrine annual targets for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions into a bill, to be introduced in the next Queen’s speech…the government believes a bill is unnecessary”.

At prime minister’s questions on 25 October 2006, Cameron continued to press Labour prime minister Tony Blair, who was still not committed to legislation.

Cameron went beyond the “Big Ask” draft by calling for an independent commission with executive powers, able to adjust the UK’s climate goals. Cameron asked Blair:

“Are we getting a bill: yes or no?…Will it include the two things that really matter: annual targets and an independent body that can measure and adjust them in the light of circumstances?”

The IfG says a former aide to David Miliband, who was then environment secretary, “remembers him commenting that Labour could not get into the position of being the only major party not in favour of the proposed bill”.

Finally, in November 2006, the Labour government confirmed in the Queen’s speech that it would introduce a new climate change bill.

Emphasising the cross-party consensus, Lord Deben tells Carbon Brief: “It was the Tories who wrote it and it was the Labour Party who accepted it – and all parties supported it.” He adds:

“It’s not just that every Tory leader since [then] has supported climate change, the Climate Change Act [and the] Climate Change Committee, but it’s simply that, actually, they ought to, because they invented it.”

The Labour government published its own draft climate change bill in March 2007 and this, after lengthy negotiation, went on to become the 2008 act.

Cameron continued to campaign for “independent experts, not partisan…ministers” to set the UK’s statutory climate targets, but this responsibility was, ultimately, left to the government.

Rutter tells Carbon Brief that, in pledging to repeal the 2008 act, Badenoch is “rejecting” a Conservative “inheritance” on climate change that runs back to Margaret Thatcher. She says:

“One of the defining features of climate policy to date in the UK has been the political consensus that has underpinned it. That may have been because Margaret Thatcher was the first leading world politician to draw attention to climate change in 1989 [via a speech at the UN in New York].”

Rutter adds that David Miliband had only been able to convince then-chancellor Gordon Brown to accept legally binding targets as a result of Cameron’s enthusiasm for the cause. She says:

“Although it was Labour legislation, brought forward by David Miliband (though implemented by brother Ed), the reason Miliband was…able to convince a sceptical Gordon Brown at the Treasury that the UK should set legally binding targets, was the enthusiasm with which new Conservative leader David Cameron embraced the Friends of the Earth ‘Big Ask’ campaign as part of his moves to detoxify the Conservative party after its 2005 defeat. Theresa May then increased the target [in 2019] from 80% to net-zero as part of her legacy. It is that long Conservative inheritance on climate action that Badenoch is now rejecting.”

What does the Climate Change Act require?

The Climate Change Act sets out an overall “framework” for both cutting the UK’s emissions and preparing the country for the impacts of climate change.

At its heart is a legally binding goal for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Originally envisaged as a 60% reduction on 1990 levels, this was quickly increased to 80%.

In 2019, amid a surge in concern about climate change, the then-Conservative government strengthened the target again to a reduction to “at least 100%” below 1990 levels, more commonly referred to as net-zero.

![The target for 2050: (1) It is the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure that the net UK carbon account for the year 2050 is at least [F1100%] lower than the 1990 baseline. (2)“The 1990 baseline” means the aggregate amount of— (a)net UK emissions of carbon dioxide for that year, and (b)net UK emissions of each of the other targeted greenhouse gases for the year that is the base year for that gas.](https://www.carbonbrief.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/cca-rag-scaled.webp)

On the pathway to this long-term goal, the act also requires the government to set legally binding interim targets known as ”carbon budgets”. These must be set 12 years in advance, to allow time for the government and the rest of the economy to plan ahead.

The carbon budgets set limits on emissions over five-year periods, providing greater flexibility than annual goals, while tackling the cumulative emissions that determine global warming.

Section 13 of the act specifies that the government has a “duty to prepare proposals and policies for meeting carbon budgets”. There is also a requirement for the government to explain how its actions will achieve its climate goals.

(In addition, the act requires the government to set out a programme of measures for climate adaptation and how it intends to meet them.)

The final key pillar of the act is the creation of the Climate Change Committee (CCC), an independent advisory body. The CCC advises – but does not decide – on the level at which carbon budgets should be set and the climate-related risks facing the UK.

The committee also produces annual assessments of “progress” and recommendations for going further, which the government is obliged to respond to, but not to accept.

Each time the secretary of state sets out their plan for a new carbon budget – taking the CCC’s advice into account – or responds to a progress report from the committee, parliament scrutinises the government’s activities.

Contrary to recent criticisms from the opposition Conservatives and the hard-right populist Reform UK, however, the act says nothing at all about how the government should meet its targets.

The only requirement is that the government’s plan should be capable of meeting its targets.

Moreover, it was the Conservatives under Cameron that had wanted to give the CCC executive and target-setting powers. This was opposed at the time by the then-Labour government.

Rachel Solomon Williams, executive director of the Aldersgate Group, notes on LinkedIn that this was a “closely debated” issue, but that, ultimately, the act puts the government “in control”:

“A closely debated aspect of the bill at the time was whether the CCC should have an executive or an advisory function. In the end, it was appointed as an expert advisory committee and the government remains entirely in control of delivery choices.”

The Conservative press release announcing Badenoch’s plan to “repeal” the act is, therefore, incorrect to state that the legislation “force[s]” governments to introduce specific policies.

(Speaking at the 2025 Conservative party conference, shadow energy secretary Claire Coutinho caricatured what she called “Ed Miliband’s…act” as requiring “1970s”-style “central planning” that “dictate[s] what products people must buy, and when”.

Just 18 months earlier, she, as energy secretary, had written of her “government’s unwavering commitment to meeting our ambitious emissions targets, including the legislated carbon budgets and the net-zero by 2050 target”.)

The press release also falsely describes the targets set under the act as “arbitrary” and falsely suggests they were set without consideration for the impact on jobs, households and the economy.

(In 2021, Badenoch herself, then a government minister, told parliament: “We will put affordability and fairness at the heart of our reforms to reach net-zero.”)

Specifically, section 10 of the act lists “matters to be taken into account” when setting carbon budgets, including the latest climate science, available technologies, “economic circumstances”, “fiscal circumstances” and the impact of any decisions on fuel poverty.

As for the net-zero target, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that reducing emissions to net-zero is the only way to stop global warming. The target was set on this basis, following detailed advice from the CCC that took climate science, economic and social factors into account.

The Conservatives have also taken aim at the CCC itself as part of their rejection of the Climate Change Act, highlighting the committee’s advice on meat consumption and flying.

In an echo of widely circulated conspiracy theories, Badenoch even told the Spectator that the CCC “wants us to eat insects”. This is not true.

Despite the framing by right-leaning media and politicians, the CCC’s recommendations for contentious topics such as meat consumption and reductions in flight numbers are modest.

The committee notes that “meat consumption has been falling” without policy interventions and says this will help to free up land for tree-planting. It says “demand management measures” to curb flight numbers “may” be needed, but only if other efforts to decarbonise aviation fail.

More importantly, the government decides how to meet the carbon budgets. It can – and often does – ignore recommendations from the CCC, including those on diets and airport expansion.

The costs and benefits of the Climate Change Act

The debate over whether to tackle climate change, how quickly and to what extent has almost invariably centred on the costs and benefits of doing so.

Those opposed to climate action have, in general, sought to exaggerate the supposed costs, while playing down the losses and damages already being caused by global warming.

Yet serious efforts to weigh up the costs and the benefits have concluded – again and again and again – that it would be cheaper to cut emissions than to face the consequences of inaction.

Indeed, this was precisely the conclusion of the landmark 2006 Stern Review, to which the 2008 Climate Change Act partly owes its existence. The review said:

“[T]he evidence gathered by the review leads to a simple conclusion: the benefits of strong and early action far outweigh the economic costs of not acting.”

More specifically, it said that the cost of action “can be limited to around 1% of global GDP [gross domestic product]”, whereas the damages from climate change would cost 5% – and as much as 20% of GDP.

When the act was passed in 2008, it was again estimated that the UK would need to invest around 1% of GDP in meeting its target of cutting emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

Since then, estimates of the cost of cutting emissions have fallen, as the decline in low-carbon technology costs has outperformed expectations. At the same time, estimates of the economic losses due to rising temperatures have tended to keep going up.

(Some years after the review’s publication, Stern said he had “got it wrong on climate change – it’s far, far worse…Looking back, I underestimated the risks.”)

When it recommended the target of net-zero by 2050, the CCC estimated that the UK would need to invest 1-2% of GDP to hit this goal. It later revised this down to less than 1% of GDP.

Most recently, the CCC revised its estimates down once again, putting the net cost of reaching net-zero at £116bn over 25 years – roughly £70 per person per year – or just 0.2% of GDP.

In July 2025, the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) went on to estimate that the UK could take an 8% hit to its economy by the early 2070s, if the world warms by 3C.

It concluded that while there were potentially significant costs to the government from reaching net-zero, these would be far lower than the costs of failing to limit warming.

Despite all this, Conservative leader Badenoch has falsely argued that the UK’s net-zero target will be “impossible” to meet without “bankrupting” the country and that the the Climate Change Act has “loaded us with costs”.

Her party has also pledged to “axe the carbon tax” on electricity generation – a significant source of government revenue – claiming that this “just adds extra costs to our bills for no reason”.

Prof Jim Watson, director of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, tells Carbon Brief that the costs of climate policies are “sometimes exaggerated” and are not the main reason for high bills:

“Policies that are in place to meet the UK’s carbon targets have costs, but these costs are sometimes exaggerated. These policies are not the primary cause of the energy price shock businesses and households have experienced over the past three years.”

Watson says that high gas prices were the “main driver” of high bills and adds that shifting away from fossil fuels “will also reduce the UK’s exposure to future fossil-fuel price shocks”.

How nearly 70 countries followed the UK’s Climate Change Act

In the interview announcing her ambition to scrap the Climate Change Act, Badenoch falsely told the Spectator that the UK was “tackl[ing] climate change…alone”. She said:

“We need to do what we can sensibly to tackle climate change, but we cannot do it alone. If other countries aren’t doing it, then us being the goody-two-shoes of the world is not actually encouraging anyone to improve.”

This is a common claim among climate-sceptic politicians and commentators, who argue that the UK has gone further than other nations and that this is unfair. Badenoch’s predecessor, Rishi Sunak, used similar reasoning to justify net-zero policy rollbacks.

The UK has indeed been a leader in passing climate legislation, but it is far from the only country taking action to tackle climate change.

The Climate Change Act was among the first comprehensive national climate laws and the first to include legally binding emissions targets.

It has inspired legislation around the world, with laws in New Zealand, Canada and Nigeria among those explicitly based on the UK model.

Indeed, 69 countries have now passed “framework” climate laws similar to the UK’s Climate Change Act, as the chart below shows. This is up from just four when the act was legislated in 2008. Of these, 14 are explicitly titled the “climate change act”.

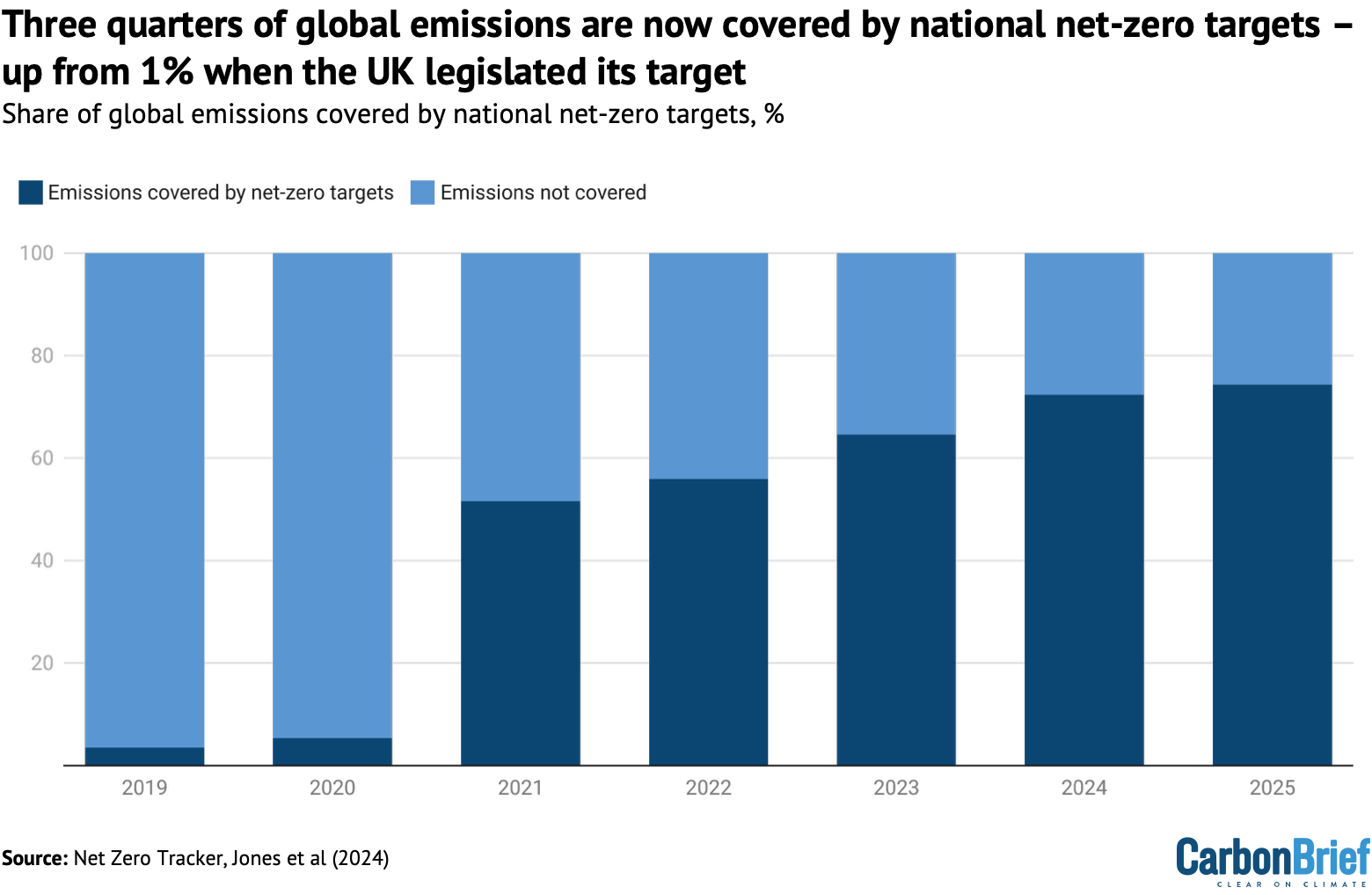

The UK was also the first major economy to legislate a net-zero target in 2019, but since then virtually every major emitter in the world has announced the target. (Not all of these targets have been put into law, as the UK’s has.)

When the UK announced its target in June 2019, around 1% of global emissions were covered by net-zero targets. By the end of that year, France and Germany brought this up to nearly 4%.

Over the following years, major economies including China and India announced net-zero targets, meaning that around three-quarters of global emissions are now covered by such goals, as the chart below shows.

(This figure would be even higher if the Trump administration in the US, which accounts for around a tenth of annual global emissions, had not abandoned the nation’s net-zero target.)

While it is true that the UK is “only responsible for 1% of global emissions”, as Badenoch has also noted, this does not mean its actions are inconsequential. Around a third of global emissions come from countries that are each responsible for 1% of global emissions or less.

Moreover, as a relatively wealthy country that is responsible for a large share of historical emissions, many argue that the UK also has a moral responsibility to lead on climate action.

This historical responsibility is implicitly invoked by the Paris Agreement, which recognises countries’ “common but differentiated responsibilities” for current climate change.

Finally, Badenoch’s position diverges from that of recent Conservative leaders.

Theresa May and Boris Johnson spoke positively of the UK “leading the world” in low-carbon technology and expressed pride about the nation’s climate record.

They framed the UK’s success in tackling climate change as a good reason to do more, rather than less. “Green” Conservatives also argue that the UK should race to gain a competitive advantage in producing low-carbon technologies domestically.

Responding to Badenoch’s plan to scrap the act, May issued a statement criticising the “retrograde step” following nearly two decades of the UK “[leading] the way in tackling climate change”.

What comes next under the Climate Change Act?

The debate over the future of the Climate Change Act, triggered by the Conservative pledge to repeal it, comes ahead of two key moments for the legislation.

First, the government has until the end of October 2025 to publish a new plan for meeting the sixth carbon budget (CB6), covering the five-year period from 2033-2037.

In 2021, the then-Conservative government passed legislation to cut emissions to 78% below 1990 levels during the sixth carbon budget period, centred on 2035. The government set out its “carbon budget delivery plan” for CB6 in October 2021, as part of a wider net-zero strategy.

In July 2022, however, this plan was ruled unlawful by the High Court for failing to publish sufficient details on exactly how the target would be met. The revised plan, published in March 2023, was once again found unlawful by the High Court in May 2024.

The High Court then gave the government a deadline of May 2025 to publish another version, later extended to October 2025 as a result of last year’s general election.

Second, the government has until June 2026 to legislate for the seventh carbon budget, covering the period 2037 to 2042. This legislation will be subject to a vote in parliament.

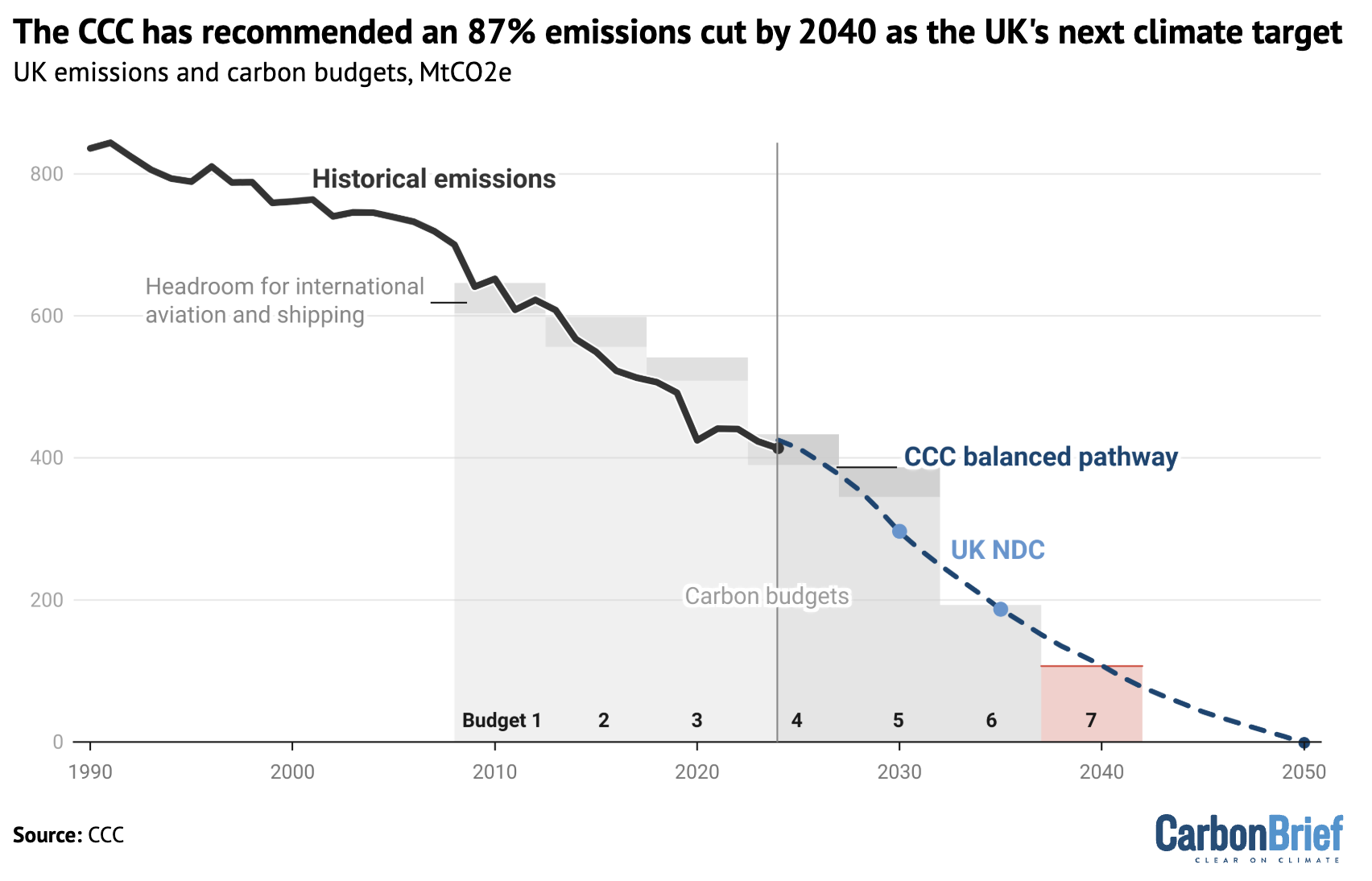

In February 2025, the CCC advised the government to set this budget at 87% below 1990 levels, in order to stay on track for the goal of net-zero by 2050, as shown in the chart below.

Both the CB6 delivery plan this October and the parliamentary vote over CB7 next June are likely to be hotly contested, with the Conservatives and Reform having come out against climate action.

After publishing two unlawful carbon budget delivery plans and ahead of a widely anticipated election loss, the Conservatives began calling for greater scrutiny around carbon budgets in 2023.

Then-prime minister Rishi Sunak said in September of that year that parliament should be able to debate plans to meet the next carbon budget, before voting on the target. He said:

“So, when parliament votes on carbon budgets in the future, I want to see it consider the plans to meet that budget, at the same time.”

Then-secretary of state Coutinho subsequently wrote that a draft delivery plan for CB7 should be published alongside draft legislation setting the level of the carbon budget. She also argued that CB7 be debated on the floor of the House, rather than in the “delegated legislation committee”.

In response, the current government has pledged to provide “further information” to parliament, ahead of the vote on CB7. In a July 2025 letter to the chair of the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee (EAC), energy secretary Ed Miliband wrote:

“Prior to parliament’s vote, we will publish an impact assessment which will clearly articulate the full range of benefits and costs of the government’s chosen CB7 target and the cross-economy pathway to deliver it.”

However, Miliband said the government would not publish a CB7 delivery plan until “as soon as reasonably practicable after” the parliamentary vote on the level of the budget.

The EAC itself is holding an inquiry on the seventh carbon budget and how the “costs of delivering it will filter through to households and businesses”. It is likely to report back in February 2026.

What would happen if the Climate Change Act was repealed?

If any future government wanted to repeal the Climate Change Act and its legally binding net-zero goal, it would not be a straightforward process.

The government would need to introduce a new bill in parliament just to repeal the act.

This process would involve seeking approval from both the House of Commons and the House of Lords before receiving Royal Assent to become law. Within the make-up of the current UK parliament, it is likely that such a bill would face significant challenges.

Any new law repealing the Climate Change Act would need to introduce new climate commitments of a similar nature – or else the UK would be in breach of several international laws and treaties, explains Estelle Dehon KC, a barrister specialising in climate change. She tells Carbon Brief:

“In short, repeal of the Climate Change Act without any replacement commitments of a similar type would be in breach of the UK’s international obligations under: the climate change treaties (so UNFCCC, Kyoto and Paris); international human rights law and customary international law, as well as specific sources like UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

Under the Paris Agreement, the UK has made pledges to cut its emissions by 2030 and 2035, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs).

The UK’s NDCs are directly informed by its domestic emissions-cutting targets, known as carbon budgets. The act specifies that the government has a “duty to prepare proposals and policies for meeting carbon budgets”.

Any move in breach of international laws and treaties could be vulnerable to legal challenges, particularly in light of a recent opinion on climate change by the International Court of Justice.

Repealing the Climate Change Act could also put the UK in opposition with its international trade agreements.

The most recent trade agreement between the UK and the EU states that each party “reaffirms its ambition of achieving economy-wide climate neutrality by 2050”.

It also contains rules on “non-regression” in relation to climate protection.