Guest post: China’s ‘capacity payments’ boosted coal-plant revenue by up to 8%

Mingxin Zhang

06.12.25

Mingxin Zhang

12.06.2025 | 2:44pmAt the start of 2024, China introduced a new system of “capacity payments” designed to help coal-fired power stations shift into a supporting role, alongside low-carbon sources.

In theory, the payments should make it financially viable for coal plants to operate less frequently, switching off unless there is insufficient output from renewables and nuclear.

However, new Global Energy Monitor (GEM) analysis finds that, despite channeling 107bn yuan ($14.9bn) to China’s coal-plant owners during its first year, there is no clear evidence that the scheme has reduced the amount of hours during which coal plants are operating.

Moreover, the analysis shows that some 70-100% of China’s coal plants received payments, depending on the province, boosting their revenues by around 5-8%.

As such, the way the mechanism has been implemented continues to raise questions about its effectiveness in supporting renewable growth and China’s wider energy-transition targets.

Rather than encouraging operators to reduce operating hours and emissions, the loose application of eligibility “guardrails” means it could be prolonging coal-plant lifetimes instead.

A ‘supporting’ role for coal

Like many other countries, China faces the complex challenge of how to decarbonise its power sector while keeping the electricity grid reliable.

Following widespread power outages in 2021 and ongoing debates over how to manage the transition, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s powerful central planner, announced a new coal capacity payment mechanism in late 2023.

The policy, which took effect in January 2024, aims to maintain grid reliability, while supporting coal-fired power plants as they shift from a primary electricity source to a “regulating and supporting” role in China’s power mix, according to Han Xue, associate researcher at China Development Research Centre of the State Council.

The mechanism provides what is essentially a monthly “standby” payment to eligible public coal plants (see below). The payments are designed to help cover fixed operating costs during periods when coal plants’ output is low, often as a result of high renewable generation. They are also intended to ensure that coal plants are available to switch on during peak demand periods.

The national framework sets payment levels at either 30% or 50% of a benchmark coal plant’s total fixed costs, which the NDRC determined to be 330 yuan ($45.8) per kilowatt (kW).

The higher 50% rate applies in provinces where the role of coal power supply is transitioning rapidly, such as Chongqing and Sichuan in southwest China as well as Hunan in the south. However, from 2026 the rate will increase to at least 50% of the fixed costs nationwide.

To illustrate the mechanism’s impact, consider a 600 megawatt (MW) coal plant running at China’s 2024 average rates. It would be operating for 4,628 hours a year and selling electricity at 0.452 yuan ($0.063) per kilowatt-hour (kWh). This plant’s annual revenue would stand at about 1.2bn ($174m) yuan.

If it receives a 30% capacity payment, roughly 59.4m yuan ($8.2m) would be added to its bank account, driving up the revenue by 4.7%. If the rate is at the 50% level, the bump rises to 7.9%.

Capacity market criticism

From the outset, the policy drew questions and criticisms. Capacity markets in other countries have also sparked debate, including in the UK, Chile and Spain.

Early in the first year of implementation of China’s capacity payments, energy media outlet China Energy News quoted experts saying that the mechanism would gradually change the coal producers’ mindset of “the more they generate, the more they earn”.

However, other “restrictions” of the mechanism, such as the 330 yuan pay rate being “too low”, would “limit” its “effect” on transition, according to the outlet.

Sign up to Carbon Brief's free "China Briefing" email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

Energy research institute the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP) had pointed out that the mechanism is restricted to coal, excluding the “participation of alternative resources” able to offer similar services, such as energy storage or demand response.

Issues with the policy meant that it could encourage older coal plants to remain online, as well as potentially “exacerbating” the continued construction of new capacity, according to RAP.

After one year of China’s programme, GEM’s analysis finds that, while the policy has contributed to coal power plant revenue, there is still little definitive evidence to show that it is shifting coal to a “supporting” role, as intended.

This raises continued questions about the mechanism’s design, its implementation and whether it aligns with China’s long-term climate and energy objectives such as the “dual-carbon” goals.

Adding to the complexity, Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at thinktank the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, highlights a regional divide in China’s power mix from 2020 to 2024 in an article for Dialogue Earth.

He says that northern provinces have made more progress towards integrating clean energy than the southern regions, which have been “complacent” due to rich hydro resources. In contrast, others have invested more in wind and solar capacity, as well as in coordinating grid operation with neighbouring areas so as to better manage variable renewable output.

These regional disparities complicate any assessment of the capacity mechanism’s impacts.

Capacity payments ‘top 100bn yuan’

Only 12 provincial governments have released lists of qualifying plants, providing rare insight into how the capacity payment policy is being implemented.

These provinces represent just 38% of the country’s total operating coal capacity, meaning most of the national implementation remains undocumented in the public domain.

This partial picture makes it difficult to assess the policy’s broader outcomes, particularly as provinces appear to apply eligibility and enforcement criteria differently.

Based on the national policy’s payment levels and the 12 provincial recipient lists, the capacity payments in these provinces alone was more than 40bn yuan ($5.5bn) in the first year of the scheme, as shown in the figure below.

Combining the total operating capacity and payment numbers from the 12 provinces that have published data with GEM’s most recent national capacity figures, our analysis estimates that the total national payout in 2024 was approximately 107bn yuan ($14.8bn).

(This figure is uncertain. Greater transparency would help clarify how the mechanism is functioning and its role in shaping the future of coal in China’s power system.)

As shown in the figure above, capacity payments vary significantly across provinces. Of those 12 provinces with detailed published data, Henan in central China received the largest share, totaling approximately 9.4bn yuan ($1.3bn), driven by both its large eligible capacity of 56.9 gigawatts (GW) and the high payment rate (50% level).

Among the 12 provinces, Guangxi (20.5GW) and Yunnan (11.2GW) in southwest China, as well as Qinghai (2.9GW) in northwest China also applied the 50% payment rate, but their smaller eligible coal capacity resulted in comparatively lower total payments.

Broadly, the rankings of total capacity payments align with those of total operating coal capacity by province, which is expected given the direct link between capacity and payment eligibility.

However, the alignment is not exact. Yunnan, for example, ranks 11th out of 12 provinces in terms of operating capacity but 8th in total capacity payments.

This reflects how provincial differences in payment rates and eligibility shares, not just installed capacity, are shaping the financial impact of the policy.

Despite restrictions, most coal capacity is eligible

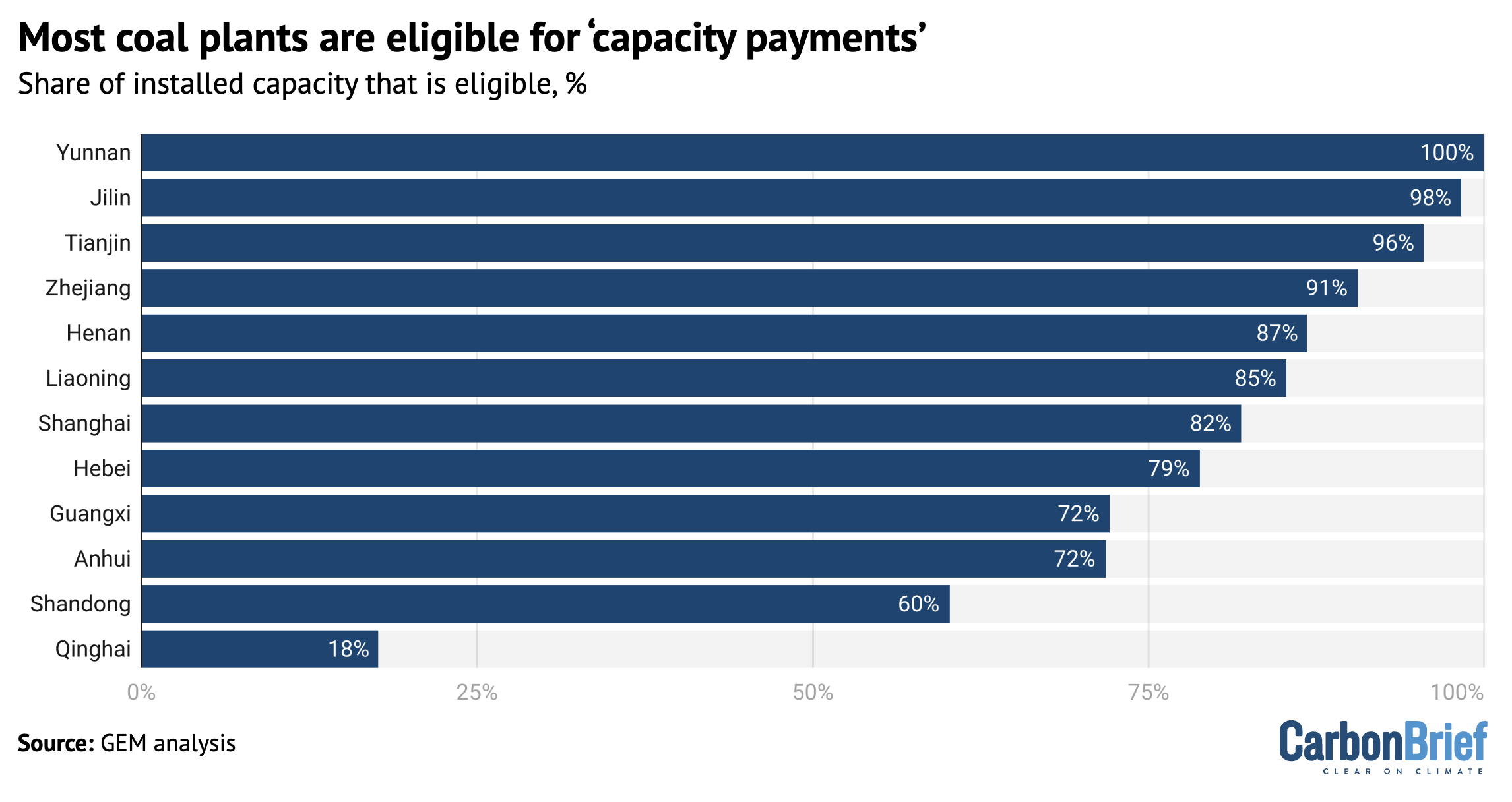

By cross-referencing provincial recipient lists with GEM’s Global Coal Plant Tracker (GCPT), it is possible to estimate the share of each province’s coal capacity receiving payments.

In almost all of the 12 provinces that published recipient lists, a large majority of coal capacity is eligible for payments, as shown in the figure below.

The NDRC national guidelines published alongside the policy announcement stipulate that only “compliant, public operating coal units” are eligible for the capacity payments. The guidelines identify three categories of coal-fired power plant units that are excluded:

- “Captive” units, which exclusively serve specific industrial or commercial entities and operate independently from the public power grid;

- Units failing to meet energy efficiency, environmental performance, or operational flexibility standards;

- Units not compliant with the broader “national plan”, a criterion that is not further clarified in the guidelines.

Despite these restrictions, most provinces with available data include between 70% and 100% of their total coal capacity under the mechanism, as the chart above shows.

In some cases, this appears inconsistent with the eligibility criteria. For example, the Mancheng Mill power station in Hebei in northern China has two 35MW combined heat and power (CHP) units, which started operating in 2018 to provide heat and power exclusively to a pulp and paper industrial park. This appears inconsistent with the “captive unit” exclusion.

In line with concerns raised by RAP, some newly built coal power plants were included in the initial provincial recipient lists, or added at a later date. For example, Beihai Bebuwan power station Unit 4 in Guangxi began operating in March 2024 and was added to the recipient list in September 2024. The inclusion of such projects could be interpreted as an incentive for new coal capacity, under the banner of grid reliability.

Although plant age is not explicitly disqualifying, coal power plants in China generally have a 30-year design lifespan. Yet older units are included in recipient lists in multiple provinces.

Shenhua Panshan power station Units 1 and 2 in Tianjin in northern China, for instance, began operating in 1994 and were retrofitted in 2023. Their continued inclusion raises questions about whether the policy supports transition, or extends the operational life of ageing assets.

It also highlights uncertainty around how retrofits will be treated, if undertaken after the policy entered force at the start of 2024, and whether such units will be firmly excluded from eligibility.

Finally, several provincial lists include smaller units, which may have limited ability to contribute to peak demand management. For example, five 57MW units from Shaoxing Binhai power station in Zhejiang, southeast China, built to provide heat demand for local dyeing and printing industries, were accredited for capacity payments.

Their actual contribution to evening peak load, when generation from solar and wind is low, is unclear from the list or other available provincial assessments.

More questions than answers?

There was only two months between the announcement of coal capacity payments and their implementation, leaving no time for pilot programmes or detailed feedback. This may help explain the ambiguities that have emerged during the provincial execution process.

Our analysis of the first year of the scheme suggests that provincial discretion has played a major role, with national criteria loosely applied in practice.

Moreover, there is no clear evidence to date that the mechanism has led to reduced coal utilisation hours, or significantly increased solar and wind generation.

While electricity generation from coal decreased in northern provinces during 2024, our analysis found that this was not the case in southern regions.

Different factors contribute to these regional differences, such as power demand and clean-energy resources. With only one year of data from the capacity payment scheme, it is not possible to attribute these changes solely to the capacity payment scheme.

To better align the mechanism with its stated goals, future adjustments could consider specifying coal-plant eligibility criteria more clearly and transparently.

Expanding the scheme to non-coal resources, such as energy storage, demand response or energy efficiency, could help it contribute to wider system flexibility and transition objectives.

Finally, ongoing monitoring of provincial implementation and energy trends will allow for a clearer assessment of how the policy evolves in the coming years.