Coal prices have halved since 2011 because of China’s “anything but coal” power plans and competition from cleaner sources of energy, the Financial Times reports. Prices will probably rebound, but analysts tell the paper the recovery may be slow.

Back home, the UK has a coal problem. Use is up a fifth in four years due in part to low prices and the government has been looking at extending the life of coal plants. German use is up 13 per cent too.

Some are saying the shift to coal, the most polluting of all fossil fuels, has been at the expense of cleaner gas and nuclear. If it persists it would be a threat to EU plans to cut emissions by 40 per cent in 2030.

So is cheap coal bad news for the climate?

Supply and demand

First, let’s take a look at today’s coal price and why it has become so cheap.

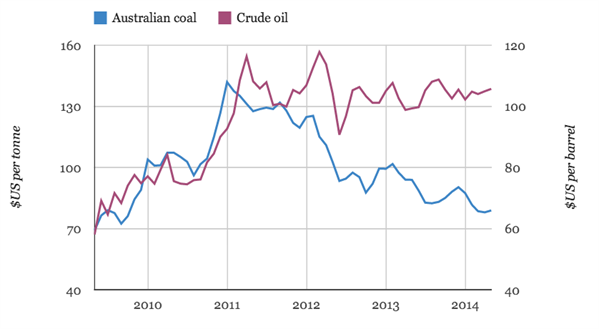

Coal prices haven’t been this low since 2009, as the chart below shows, and have almost halved since a peak in 2011. Over the same period crude oil has remained above the historically unprecedented $100 per barrel level (purple line). So low coal prices aren’t being caused by generally weak demand for energy.

Source: Index Mundi commodity price indices

The latest coal price outlook from analysts Thomson Reuters notes that demand remains “bearish” (tending to fall).

Luke Sussams, senior researcher at thinktank the Carbon Tracker Initiative says the low prices have come about because markets are suffering from over-supply. “I don’t think prices have fallen all the way yet,” he adds.

The consensus range of predictions is that the coal price will rise but remain well below peak levels during 2015 and 2016. Some, like Sussams, are expecting further price reductions.

It isn’t only Australian coal firms that are struggling as a result of low prices. Some Chinese mining companies are reported to be selling at a loss and many smaller players in the country are expected to go out of business.

Shares in several major US coal firms including Peabody Energy have lost three-quarters of their value since 2011.

There are a number of reasons why coal prices have fallen so far explains Paul Baruya, market analyst for the IEA’s Clean Coal Centre.

Stockpiling at power stations has reinforced already slower demand since the economic slowdown, he says. Cheap shale gas in the US has also been a factor, with excess US coal spilling over into overseas markets.

Another cause of low coal prices is a glut of shipbuilding in 2007-8 that expanded the global fleet just when demand dropped out of the market, causing the cost of shipping coal around the globe to plummet.

Producing at a loss

Production levels have not slackened despite weaker demand with the top exporter, Indonesia, boosting output by nearly 10 per cent in 2013.

Australian firms have also raised production, despite their financial troubles. Many are locked into expensive rail and shipping contracts that make it cheaper to sell coal at a loss than to halt production. Some Australian companies have been forced to try to sell uneconomic mines and ports.

Sussams says these are early examples of ‘stranded assets‘, where investments in fossil fuel resources cannot be paid back.

“I think we’re seeing asset stranding already and will see more as the market tries to correct oversupplyâ?¦ it isn’t only mines but coal plants that are becoming stranded. The logical conclusion is that emissions have to fall.”

The stranded asset concept has usually been put forward as a consequence of climate action. The coal market appears to be demonstrating this in reverse, Sussams says, with similar effects emerging despite the lack of strong global climate action.

But while low prices might be causing pain for coal mining firms they can provide relief for coal-fired electric utilities in tightly regulated markets like China, Baruya says. These firms are prevented from passing on cost increases to consumers but will have become more profitable as a result of low coal costs.

Even if the cost of coal were to rise substantially, coal-fired power is likely to remain much cheaper in Asia than power from gas. Exports of shale gas from the US won’t change that. Even though the gas is cheap, transport costs are not.

Will low coal prices lead to a surge in coal-fired power output and emissions? That depends, says Baruya. Power output cannot grow in a vacuum: there needs to be a corresponding rise in demand as a result of GDP growth.

Structural, not cyclical

So the key question, says Sussams, is whether low coal demand and low prices reflect structural changes in the global economy or whether the cyclical ebb and flow of market supply and demand has been more important.

The indications are that structural changes are at work, Sussams continues.

For example US coal consumption grew last year but that is unlikely to last as its overall electricity needs have fallen.

At least 50 gigawatts of US coal capacity was due to be retired by 2020 even before President Obama announced his plan to cut US power plant emissions. Plants face the combined pressure of cheap shale gas and tightening air pollution rules.

A similar situation prevails in Europe, even though coal use in the likes of the UK and Germany has recently risen. The general consensus is that this has been “a very short term response”, says Sussams.

A recent analysis from green thinktank the Heinrich Böll Foundation agrees, saying that current additions to the German coal fleet are “a one-off phenomenon”. Like in the US, coal plants across the EU face closure in response to stricter air pollution rules.

In any case coal demand in the EU and US is relatively insignificant on the global scale, with China responsible for four-fifths of the increase in demand for coal since 2000.

Peak coal?

Last year Chinese coal use grew just three per cent according to BP. That is the lowest growth rate in years and streets away from the double-digit growth rates recorded in the 2000s.

Some are predicting China’s coal use will soon peak, through others are less sure. Financial analysis firm Citi Research says Chinese coal demand may flatten or even peak before 2020.

Sussams expects to see a structural shift to lower economic growth and coal demand in China, as it moves from a workshop-based to a consumer-based economy. The country’s troubles with smog are another reason to expect structural change in the demand for coal.

There is a wide range of predictions for peak coal in China. Sussams says he’s seen dates ranging from 2015 to 2030. Recent discussions of a possible carbon emissions cap make an earlier coal peak for China more plausible, he says.

Excess coal supplies

China is building hundreds of gigawatts of new coal plant but most of it is to replace old and inefficient generation. If Chinese demand really does fall away, who will pick up excess coal supplies?

India is the obvious answer. It is currently building around 100 gigawatts of new coal capacity, says Baruya. But Sussams says that India’s capacity to bring coal plants online at the scale necessary for it to pick up China’s pace is limited by its access to capital.

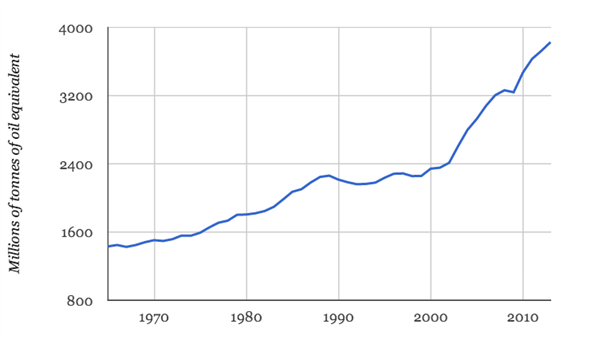

For now, coal use just keeps on growing as the chart below shows. Its share of the global energy mix reached a 40 year high in 2013 up from 25 to 30 per cent in the last decade.

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2014

Expected US and EU coal-plant closures probably won’t counterbalance new Asian additions, Baruya thinks, so that line won’t be turning south just yet.

That means despite the woes of some in the coal industry analysts are arguing that rumours of the death of coal have been greatly exaggerated. Predictions from the IEA, BP and others are for coal demand to keep on rising for years to come.

Very little will dent the developing world’s “prodigious” appetite for coal-fired power according to Reuters market analyst John Kemp.

He writes:

“There is no conceivable energy future over the next 30 to 40 years in which coal does not play an enormous role.”

Coal emissions were responsible for half the increase in the global total over the past decade and continued coal emissions growth are not thought to be compatible with limiting global warming to 2 degrees.

All this means that without new efforts to curb coal use or install carbon capture facilities, coal remains likely to steer the world towards dangerous climate change – whether coal prices stay low or not.

A version of this blog was originally published on 23 June.