Q&A: How ‘Fit for 55’ reforms will help EU meet its climate goals

Multiple Authors

07.20.21Multiple Authors

20.07.2021 | 3:43pmThe European Commission has published proposals on how the European Union should reach its legally binding target to cut emissions to 55% below 1990 levels by 2030.

Spanning thousands of pages, its “Fit for 55” package includes a wide range of reforms, covering the key EU climate policies, as well as various related laws on transport, energy and taxation.

The package of 13 proposals includes tightening the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), pricing emissions from heat and transport in a parallel ETS and adding a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) to tax high-carbon imports, such as steel and cement.

Other proposals include phasing out petrol and diesel car sales across the bloc by 2035, raising targets for renewables and energy efficiency, setting higher, binding national targets for sectors outside the EU ETS and, separately, setting binding goals for carbon dioxide (CO2) removals.

A new “social climate fund” is proposed to help vulnerable households disproportionately affected by higher fossil fuel prices, offering “temporary” income support and longer-term investment.

Lengthy negotiations will now begin between the EU’s executive branch, member state governments and the European Parliament. Many details are likely to change before the reforms are adopted.

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief explains what is in the commission’s proposals and how they intend to “fundamentally transform” the EU economy and society on the way to net-zero by 2050.

- The ‘Fit for 55’ package

- Expanding and tightening EU carbon markets

- Pricing high-carbon imports with a border tax

- Higher targets for renewables and energy efficiency

- National emissions limits under the ‘Effort-sharing regulation’

- Ending aviation and shipping’s exemption from energy taxation

- Targeting an end to combustion engine cars

- Including land use and forestry in EU targets

- Boosting tree-planting with the EU forestry strategy

The ‘Fit for 55’ package

Collectively, the EU’s 27 nations are a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for some 3.5bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent in 2019, behind only China, the US and India.

Ahead of the Paris Agreement in 2015, the bloc had committed to cutting its emissions to “at least 40%” below 1990 levels by 2030 and to 80% below 1990 by 2050.

In December 2020, political leaders from the EU member states endorsed a new target to cut emissions to “at least 55%” below 1990 levels by 2030 and to reach “climate neutrality” (net-zero) by 2050.

These targets were made legally binding by the European Climate Law, which formalises the aims of the European Green Deal. The law was agreed in April and formally adopted in June.

The EU has also committed internationally to its 55% reduction target, in its revised “nationally determined contribution” to the Paris Agreement.

The make-or-break decade has already started.

— European Commission 🇪🇺 (@EU_Commission) July 14, 2021

Our first major climate milestone will be a 55% reduction of emissions by 2030.

And by 2050, we aim to make the EU climate neutral.

Today, we present concrete proposals to reach these goals: https://t.co/h20a4iwgap#EUGreenDeal pic.twitter.com/jw7l1G6V7e

Whereas many countries have now increased their climate ambition through long-term net-zero targets, few have spelt out the details of how their goals will actually be met.

The new “Fit for 55” proposals from the commission mark the beginning of the process of reform that will, ultimately, aim to align the EU’s laws and policies with its overall climate targets.

The proposals reflect on progress to date, with EU emissions now 24% below 1990 levels, as well as the challenges to come – particularly in sectors such as transport, where emissions have risen.

The commission proposals do not cover all of the changes needed to deliver the 2030 and 2050 goals. Another package is due in December, covering building efficiency rules and gas markets.

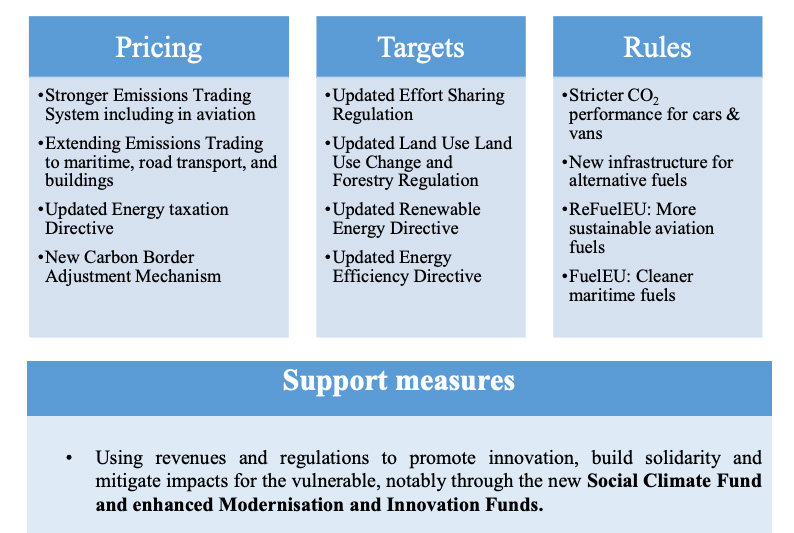

Overall, the package contains proposals for strengthening eight existing pieces of legislation as well as five new initiatives. The commission says that this includes a “careful balance” between pricing, targets, standards and support measures, shown in the figure below.

Although drafts of many of the documents were widely leaked before the announcement, it will take time for the details to be understood, analysed and haggled over.

Some of the reforms have strong support from certain member states and attract deeply held opposition from others. Negotiations over the package will take years and could involve horse-trading over national priorities in each area.

The plan to include heat and transport in an emissions trading scheme – a priority for Germany, which has a domestic version – is already attracting criticism from the likes of Poland.

It may be difficult to negotiate a “grand bargain” between member-state priorities across the Fit for 55 package, says Johanna Lehne, senior policy adviser at climate thinktank E3G, not least because the European Parliament also has a say in the process.

There will also be intense lobbying by NGOs, activists and various parts of industry – as well as opponents of climate action. (There is overwhelming public support for ambitious EU climate action, according to a recent poll carried out by Eurobarometer.)

The CBAM is likely to be particularly charged, both within the EU and internationally, as it would impose import taxes on goods arriving from outside the EU, while triggering a shift away from the existing approach to protecting industry from “carbon leakage”.

In a statement ahead of the launch, E3G said:

“A deep analysis of the thousands of pages of proposals will take weeks, and the negotiations between European Parliament and national government years.”

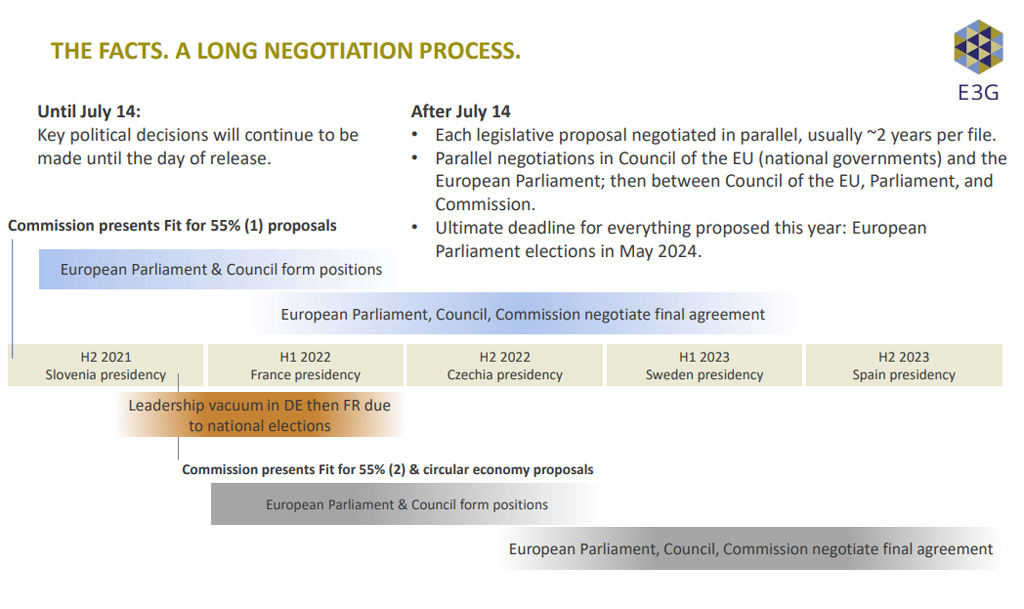

According to E3G, negotiations over the package could continue for more than two years under the six-monthly EU presidencies of Slovenia, France, Czechia, Sweden and Spain (timeline below).

The “ultimate deadline” for agreement is the May 2024 European Parliament elections, E3G adds.

In its communication summarising the package, the commission invites the European Parliament and the Council of the EU to “swiftly” begin their work on the proposals and “ensure that they are treated as a coherent package, respecting the multiple interconnections between them”:

“The commission has now presented the necessary proposals for the EU to fulfil our commitments and targets, and to genuinely embrace the transformation that lies ahead.”

Expanding and tightening EU carbon markets

One of the most significant changes being proposed by the commission relates to the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the cap-and-trade carbon market that currently regulates airlines and industrial sites responsible for nearly half of the bloc’s overall emissions.

There are two parts to the reforms. The first, more dramatic proposal is to significantly increase the scope of EU carbon trading to cover emissions from shipping, buildings and road transport.

The second part of the reforms is a series of administrative changes designed to bring the existing EU ETS into line with the more ambitious 2030 EU climate target.

Under the commission proposals, emissions from buildings and road transport would be regulated by a parallel ETS, operating separately from the existing scheme, but with a similar design. Revenues would be reserved to support vulnerable households and invest in climate measures.

The proposal to include buildings and transport in an ETS was the focus for much of the media coverage ahead of the “Fit for 55” launch. Reuters called it “the biggest revamp…since the policy launched in 2005” and French MEP Pascal Canfin was widely quoted calling it “politically suicidal”.

The parallel ETS would start to operate in 2025, with upstream energy suppliers obligated to buy emissions allowances sufficient to cover the use of their products from 2026. The new and existing ETSs could be merged in the future.

Unlike the existing EU ETS, where around half the allowances are given away for free, the buildings and road transport scheme would run under full auctioning.

As with the existing scheme, the total number of allowances in the new ETS would be subject to a shrinking “cap” that limits the number of emissions and declines each year according to a “linear reduction factor” (LRF) that would start at 5.15%.

The new ETS would, ultimately, cap emissions from buildings and transport at 43% below 2005 levels by 2030, with the LRF being adjusted as necessary to meet the target.

Also similar to the existing scheme, the parallel ETS would have a “market stability reserve” (MSR). Further allowances would be added to the reserve or released from it for auction, under certain conditions, designed to stabilise market prices.

The extension to buildings and transport is widely seen as controversial, with potentially regressive social impacts unless higher fuel costs are addressed with other policies.

2. Probably the most far-reaching & controversial element of the proposals is the extension of the Emissions Trading System to the buildings & transport sector. Could have major ramifications for the existing policies, the price of fossil fuels & equity. https://t.co/a6RUBO40IM

— Jan Rosenow (@janrosenow) July 14, 2021

A study from consultancy Cambridge Econometrics – published before the commission proposals had been finalised – concluded that including buildings and transport would have “little additional impact on emissions…but would significantly increase living costs for poorer households”.

The Regulatory Assistance Project concluded that the move to price these emissions should be “gradual and measured” and that “a comprehensive and ambitious buildings policy framework” with “significant efforts” to protect poor households would be needed, alongside emissions trading.

Media coverage of the measure and responses from NGOs and thinktanks have frequently invoked the “boogyman” of the “gilets jaunes” protests in France in 2018/19, as a warning against any policy that would raise consumer prices as a result of carbon pricing.

A blog by historian Adam Tooze argues against simplistic readings of the gilets jaunes crisis, however, in the context of the commission proposals on pricing heat and transport carbon:

“The lesson of the gilet jaunes crisis is not that carbon pricing is impossible, but that it has to be done with an awareness of the distributional effects. If you want to adjust energy prices you have to offset the higher costs with redistributive payments to those whose incomes are squeezed most severely.”

With the potentially regressive and contentious impact of its proposals in mind, the commission has also set out plans for a new “social climate fund” – heavily promoted at the launch – with €72bn from the EU’s central budget during 2025-2032 that should be match-funded by member states.

It says this would be equivalent to 25% of the revenues from the new ETS. Member states would have to publish “social climate plans”, by June 2024, for approval by the commission, setting out how they would spend the money, giving a one-year lead before higher prices impacts are felt.

The pot of money would be allocated between member states according to their share of vulnerable households, with over half going to Poland, France, Italy, Spain and Romania.

In a speech launching the Fit for 55 package, commission president Ursula von der Leyen said the fund “embodies our commitment to a just transition” and added:

“The fund can compensate vulnerable groups for higher costs of heating and transport fuels, and help invest in cleaner solutions…It can provide temporary direct income support, help citizens finance zero-emission heating or cooling systems, or purchase a cleaner car.”

In terms of the existing EU ETS, the commission is proposing to include maritime emissions in the scheme and to tighten the emissions cap more quickly to align with the new 2030 target.

It wants to increase the LRF from 2.2% to 4.2% so as to cut EU ETS emissions to 61% below 2005 levels by 2030, some 18 percentage points more than under the existing rules. At the same time, the inclusion of shipping adds about 7% to the emissions regulated by the scheme.

Thread: Following today’s #FitFor55 package, here’s my initial analysis of the #EUETS revision proposal. Long story short: It becomes more difficult to pollute, but sustainable frontrunners are still disadvantaged compared to laggards.

— Leon de Graaf (@Leondegraaf7) July 14, 2021

The commission is also proposing a “one-off reduction” of 117m allowances available for auction, to correct the trajectory of the market in the years before the tighter LRF kicks in.

Other changes being proposed include a tightening of the process of giving free emissions allowances to sectors at risk of carbon leakage, with free allocation continuing until “at least 2030”.

Sectors subject to the new carbon border adjustment mechanism would see their free allocation phased out by 2035 (see below).

The reforms would also end free emissions allowances for aviation within the EU by 2026 and, for flights to or from the bloc operated by EU-based airlines, they would implement the UN’s “Corsia” scheme for capping international aviation emissions.

The existing EU ETS would be extended to 100% of maritime greenhouse gas emissions due to voyages between EU member states, as well as 50% of emissions from “extra-EU” voyages, meaning outbound voyages from the EU and inbound ships arriving from elsewhere.

This would amount to around two-thirds of the EU’s overall shipping emissions from domestic and international maritime transport, according to the commission.

(The proposal to only include half of emissions from extra-EU shipping is explained as “a practical way to solve the issue of common but differentiated responsibilities and capabilities, which has been a longstanding challenge in the UNFCCC context”.)

Shipping operators would have a three years transition, with an obligation to buy allowances for 20% of regulated emissions in 2023, 45% in 2024, 70% in 2025 and 100% in 2026.

Further changes proposed by the commission relate to the use of auction revenues from the sale of emissions allowances on the existing and new ETSs, which mostly accrue to member states.

Under the commission proposal, member states would retain control over the money, but would be obligated to spend all auction revenues in listed climate- and energy-related areas. Currently, they only have to spend half the money on supporting emissions reductions.

This section of the legal text includes binding language (“shall”) on the use of revenues that is likely to trigger political disagreement and negotiation, as the details of the proposals are worked out.

The list of allowable uses for the money is also likely to become a point of negotiation.

In addition to existing areas they can fund, such as renewables or energy efficiency, the proposals say member states could use the money to support the decarbonisation of heating or cooling and to accelerate the take-up of electric vehicles and related infrastructure.

💥💥ERCST Publications After the Fit for 55 Package!

— ERCST (@ERCST_org) July 16, 2021

1) Revision of the EU ETS – https://t.co/wx6lz8pjdE

2) The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – https://t.co/W2Iw2QkZPS pic.twitter.com/hSHdwfvnxO

The commission is also calling for changes to the “modernisation fund” that supports power-sector modernisation in poorer member states, using a small percentage of EU ETS auction revenues.

Under the existing rules, member states have wide latitude to choose how they spend this money, but the reforms would exclude investments in fossil fuels and target 80% towards “priority” areas.

According to the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST), this would prohibit investments in coal-to-gas switching, for example.

The “innovation fund”, designed to “support breakthrough innovations towards climate neutrality” with the revenues from selling 450m EU ETS allowances would be boosted with another 50m EU ETS allowances and 150m allowances from the buildings and transport ETS.

In addition to its existing remit, it would support projects in the maritime sector, as well as “carbon contracts for difference”, a new instrument designed to help bring innovative industrial decarbonisation technologies to market by bridging the gap of high initial costs.

In a briefing sent to journalists, Sebastien Rilling, analyst for EU power and carbon markets at information provider ICIS, said that the commission proposals, as they currently stand, would push EU ETS prices from current levels of around €50 per tonne to €90/t by 2030.

However, Rilling added that the European Parliament and member states governments can be expected to challenge the proposals.

Pricing high-carbon imports with a border tax

Probably the most widely anticipated part of the commission proposals is its plan to tax certain high-carbon imports via a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

In her 2019 manifesto as candidate to become European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen said she would “introduce a carbon border tax to avoid carbon leakage”.

Carbon leakage occurs where industries subject to a carbon price lose market share to competitors from other jurisdictions, where the carbon price is lower or non-existent.

Sectors thought to be at risk of carbon leakage currently receive free allowances in the EU ETS and member states can add compensation for the indirect carbon costs of higher electricity prices.

Evidence suggests carbon leakage has been minimal in practice. This shows existing protections have been effective, according to the commission proposal, but it adds that this has come at the cost of the “carbon price signal [being] significantly reduced”.

A Q&A on the measure explains: “[Free allocation] has been effective in addressing the risk of leakage, but it also dampens the incentive to invest in greener production at home and abroad.”

Following von der Leyen’s appointment as president later in 2019, her commission’s European green deal gave a more nuanced justification for the idea of a CBAM.

It narrowed the focus of the proposal to “selected sectors” and made more explicit reference to a second role for the CBAM, as leverage over other countries, stating the measure would be introduced “should differences in levels of ambition worldwide persist”.

Moreover, the green deal made clear that the CBAM would be “an alternative” to existing protections against carbon leakage under the EU ETS, namely free allowances.

Finally, the text said the measure would be “designed to comply with World Trade Organization [WTO] rules and other international obligations”.

WTO chief @NOIweala talking about “greening trade”, reiterates wind/solar being cheapest in many countries

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) March 31, 2021

“WTO rules must support” climate action

“need to look at” border carbon adjustments and if it accords with WTO rules#NetZeroSummit pic.twitter.com/Ew3Scur2e7

The proposed CBAM would come into force in 2023, with a three-year transition phase consisting only of reporting requirements. Payments for emissions would be phased in over another 10 years from 2026-2035 during which the obligation would be progressively ramped up.

In a Q&A on the proposal, the commission explains how it would work:

“EU importers will buy carbon certificates corresponding to the carbon price that would have been paid, had the goods been produced under the EU’s carbon pricing rules. Conversely, once a non-EU producer can show that they have already paid a price for the carbon used in the production of the imported goods in a third country, the corresponding cost can be fully deducted for the EU importer.”

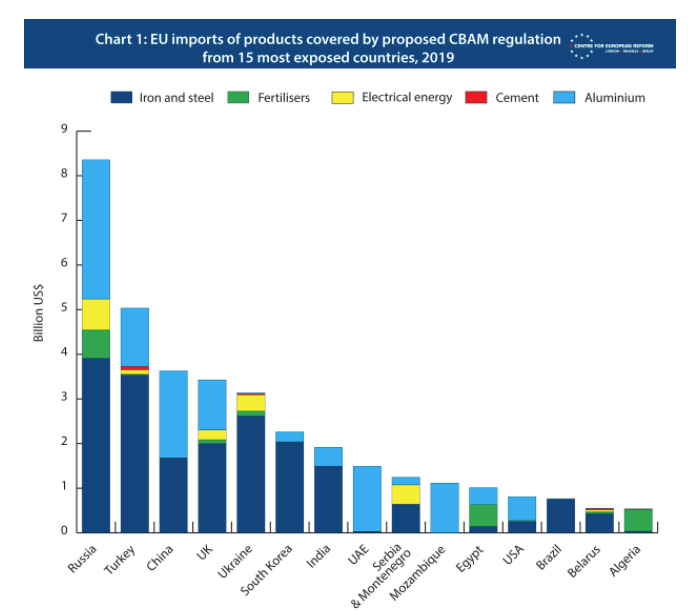

The commission is proposing a CBAM for imports in five sectors, namely iron and steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers and electricity. The proposal points to it later expanding to more sectors.

Current imports in the five sectors represent around 200m tonnes of CO2 emissions, according to a briefing shared with journalists by data provider ICIS.

Switzerland would be exempt from the CBAM as its ETS is linked to the EU scheme. Others, such as Norway, would also be exempt as they participate in the EU ETS directly. The UK ETS is not currently linked to the EU ETS, meaning UK exporters would have to pay the CBAM.

Russia would be hardest hit, exporting relevant goods worth more than €8bn in 2019, according to the Centre for European Reform, followed by Turkey (€5bn), China and the UK (each around €3.5bn. This is shown in the chart, below.

Importers would have to register with a regulator and buy carbon allowances (“CBAM certificates”) to cover the emissions embedded in their products.

Only emissions directly produced by importers would be counted, also called “scope 1” emissions. Indirect emissions associated with purchased heat or electricity (“scope 2”) would not count, but would be reviewed in 2026 with a view to future inclusion in the scheme.

EU producers would continue to receive free allowances during 2026-2035, equal to a benchmark, based on the 10% of producers in their sector with the lowest emissions.

Emissions embedded in imports would be calculated in a three-tiered approach, depending on data availability, with the default being verified actual emissions.

If an importer were unable to provide data on its actual emissions, it would have to pay an amount based on the average for comparable goods from the exporting country.

Finally, if this data were also to be unavailable, then emissions would be assumed equivalent to the 10% worst performing installations for comparable products in the EU.

From 2026 onwards, EU producers would progressively lose 10% of their free allowances each year and importers would have to buy an equivalent number of CBAM certificates.

Importers would have the option to prove that they have already paid an equivalent carbon price.

The price of CBAM certificates would be tied to the average of EU ETS prices in the previous week and would be updated weekly.

The allowances would not be tradable and could not be “banked”, meaning they could not be bought in the current year for use in the future, as a hedge against rising prices.

Why do we need a ‘Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism’?

— European Commission 🇪🇺 (@EU_Commission) July 17, 2021

As we raise our climate ambition, we need to prevent business moving abroad to countries with weaker rules.

The Mechanism will ensure that companies importing into the EU have to pay a carbon price as well.#EUGreenDeal pic.twitter.com/Xz9COP8080

The commission estimates that the measure would raise around €9bn in 2030, based on its assumption that EU ETS prices will reach around €85 per tonne.

Some €7bn of this would come indirectly from EU producers buying EU ETS allowances that they currently get for free. Another €2bn would come from importers paying the carbon border tax.

The estimated €2bn raised directly by the CBAM in 2030 would go towards the EU’s “own resources”, making it a revenue-raising tool to help the commission pay back its €750bn in pandemic recovery funds.

The details of the scheme will be negotiated between member state governments, the European Parliament and the commission over the months and years ahead.

Key questions include the treatment of free allowances under the EU ETS, the use of CBAM funds, compatibility with WTO rules and impacts on the EU’s relationship with international partners.

According to Clean Energy Wire, France and Germany have been supportive of the CBAM proposals, as has Poland. It says “positive remarks” have also come from Italian and Spanish officials, but notes that detailed positions will only now start to emerge.

Member states including Denmark and Sweden are more cautious, seeing the initiative as potentially protectionist if it is not “very carefully” designed.

According to Politico, France is the “leading voice in favour”, whereas Germany is only “ambivalent”, fearing knock-on or retaliatory impacts on its export-intensive economy.

According to the ERCST, EU producers could lose out as they would not get relief from carbon prices when they export goods overseas. It says they “will rally against the lack of provision for European exports, which will be vulnerable to leakage as free allocation subsides”.

EU heavy industry is in favour of the CBAM, as long as it continues to receive free allowances, whereas the commission sees this as “double protection” that “should not coexist in the long run”.

The aluminium industry is calling to be exempted from the initial phase of the CBAM, arguing that importers could send their lowest-carbon output to the EU in order to avoid the levy, the Financial Times reported ahead of the “Fit for 55” launch.

Although the CBAM has been designed with WTO rules in mind and experts argue it is possible to design a WTO-compliant scheme, the measure could still face challenges.

Moreover, ahead of the crucial COP26 climate summit in November, the potential for tension over the CBAM could be seen as unhelpful when cooperation is vital to the success of the talks.

As a briefing from climate thinktank E3G explains, border carbon adjustments are “controversial because they represent the external projection of a country or region’s climate policies”. It adds:

“Critics argue that this represents a break from the multilateral approach to climate action: where the emphasis has been on a collective effort to cut carbon emissions. BCAs, by contrast, could unilaterally impose higher standards on trade partners.”

The briefing argues that the EU will need a “complementary cooperation agenda” that makes a “credible offer” to international partners in order to win their support for the CBAM:

“Several academic papers suggest that revenues should be earmarked for international climate funds or disbursed to third countries to clearly position BCAs as a non-protectionist measure and to garner support among international partners.”

The measure is already making waves internationally. A Clean Energy Wire briefing on the proposal reports concerns that it could spark a “trade war”, triggering retaliatory tariffs.

Politico points to pushback over the CBAM proposal from the US, China, Australia and others. Russia has argued the CBAM would “contravene” WTO rules, EurActiv reported last year.

In a joint statement issued in April, the BASIC group of Brazil, South Africa, India and China “expressed grave concern” over the idea, calling it “discriminatory”.

The EU released its #CBAM proposal today as part of its #Fitfor55 package

— Johanna Lehne (@JohannaLehne) July 14, 2021

A 🧵on the political economy of it all (1/n)https://t.co/IzD9xBCwtm

One South African trade official told Climate Home News “they were concerned developing nations would shoulder most of the burden” and compared the CBAM to Trump’s border wall with Mexico.

Michael Liebreich, senior contributor to BloombergNEF writes that he is supportive of a CBAM in principle, but fears the implications of a poorly designed intervention:

“The current focus on CBAMs risks raising tensions that could derail climate diplomacy and trade liberalisation, at a time when those are needed more than ever.”

A July 2020 comment article for Technology Review said a CBAM would be “hypocritical” and “unust”. The piece said such proposals were “the latest form of economic imperialism and are antithetical to the principles of equity enshrined in the Paris Agreement”.

There are particular fears that a CBAM could unfairly penalise the world’s least developed countries (LDCs), unless they are exempted from or compensated for its impact.

According to the Centre for European Reform, LDC exports to the EU are small, meaning an exemption would “not materially undermine” the bloc’s carbon reduction efforts.

An editorial in the Financial Times backed the CBAM, saying it was “a necessity”.

Along with international pushback, the CBAM discussions have also triggered introspection on the part of high-carbon exporters that may be affected by the measure.

For example, in December, several officials from the Bank of Russia wrote that the CBAM “may affect almost 42% of Russian exports”. This demanded a response from government and the private sector, they argued, perhaps including a domestic Russian carbon market:

“The private sector and the state should take active measures to maintain economic competitiveness in the world of growing climate risks.”

Analysis published by the Sydney Morning Herald argued it would be better to “pay a carbon tax to our own government” rather than “someone else’s” under the CBAM. The Australia Institute called a CBAM a “serious risk for some goods in Australia” and added:

“Under all circumstances, the safest course of action is for Australia to diversify its production by investing in the production of clean exports.”

(The Australian Industry Group sees the CBAM as a limited risk, saying: “Early results suggest Australia’s exports to Europe will be about as profitable after CBAM as they are today.”)

The EU is not alone in considering the idea. The UK is reportedly “looking into” it and the Canadian government has pledged to consult on border carbon adjustments.

The Democratic election platform pledged to apply a “carbon adjustment fee at the border” and a group of Democratic senators recently introduced a concrete proposal for a border tax, though it is not clear if the Biden administration supports the specific details.

Higher targets for renewables and energy efficiency

The package also includes updates to the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and its Energy Efficiency Directive (EED), which set targets for the share of renewables and lower energy use.

The RED reform proposal would increase the 2030 target for renewables from 32% of the EU energy mix to 40%, roughly double the level reached in 2019 of 19.7%.

As for the EED, the reform proposed by the commission would increase the existing non-binding goal of keeping energy use 32.5% below projected levels in 2030 – equivalent to limiting primary energy use in the bloc to 1,128m tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe).

This would be replaced with a binding target of keeping energy use to 39% below projected levels in 2030, equivalent to a limit of 1,023Mtoe.

The commission says its proposals not only target an increased share of renewables – with sub-targets for transport, heat, buildings and industry – but also aim to “creat[e] an energy system able to integrate large shares of renewables for end users as efficiently as possible”.

7. The current RES target of 32% by 2030 will be increased to 40% roughly doubling the share of solar, wind and other renewables in Europe’s energy mix by the end of the decade. The good news is that we can do even more and move even faster. https://t.co/35DF0aXMul

— Jan Rosenow (@janrosenow) July 14, 2021

The commission calls bioenergy a “key part of the EU energy system” and says its “sustainable use contributes to the decarbonisation of the EU economy”. It sets out further rules on the sourcing of bioenergy, including to “minimise” the use of “quality roundwood” for energy production.

The changes have been roundly criticised by some NGOs and thinktanks for failing to stop “an explosion in the amount of wood being harvested for ‘renewable heat’”.

For buildings, the commission is proposing an indicative goal of getting at least 49% of energy needs from renewable sources by 2030, including renewable electricity, heat pumps, solar thermal and district heating.

This is to combine with its “Renovation Wave Strategy”, published last year, to help shift building heat and cooling towards renewable sources. Later this year, the commission will also set out reforms to the energy performance of buildings directive.

#Fitfor55, #Heating and #Cooling beyond the #RenewableEnergyDirective. A quick thread.

— Pedro Guertler (@enfinnEU) July 15, 2021

Levers to decarbonise heating and cooling – responsible for 50% of energy consumption with 75% provided by fossil combustion – are highly fragmented across the proposals so far. pic.twitter.com/dsdTtwLzJ1

The energy efficiency directive reforms include a first EU-level definition of energy poverty, as well as a target for member states to reduce final energy consumption by 1.5% a year from 2024-2030, nearly double the current required rate of 0.8%.

National emissions limits under the ‘Effort-sharing regulation’

Along with the EU ETS and the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation, the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) is one of the three pillars of the EU’s climate targets.

The ESR applies to sectors not included in the EU ETS and sets binding annual national emissions targets for member states, amounting to an overall cut of 29% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

The covered sectors, namely buildings, transport, agriculture, waste and some industrial emissions, collectively account for around 60% of EU emissions.

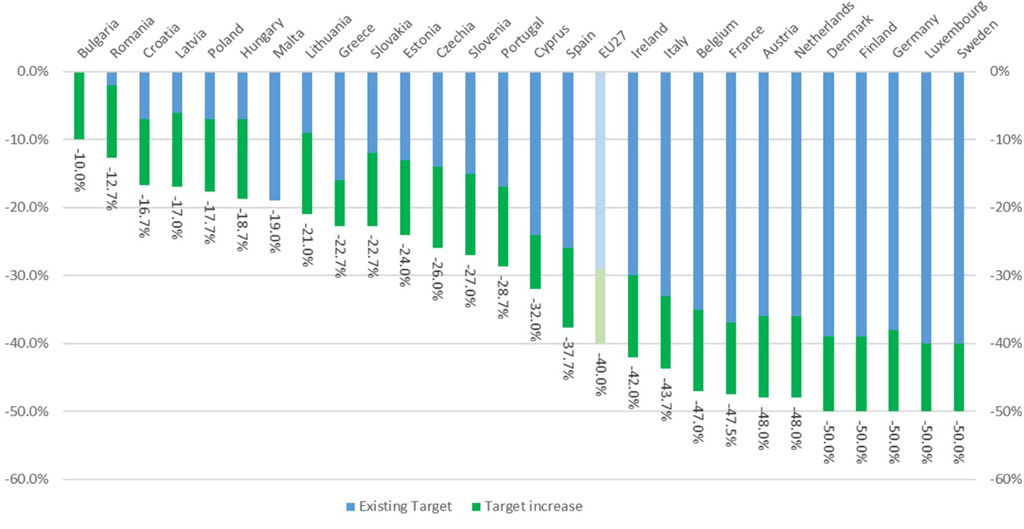

To meet the bloc’s new climate target by 2030, the commission is now proposing to reduce ESR emissions by at least 40%, with member-state targets ranging from cuts of 10-50%.

The idea of “effort sharing” is that member states contribute in a “fair and just manner to EU climate action”, with national targets set based on GDP.

The chart below shows the division of ESR targets between member states, with the blue bars indicating existing 2030 targets and the green bars indicating the commission’s new proposals.

However, the “fairness” of the ESR has always been a source of controversy and will likely be a source of conflict in the months of discussions to come.

The ESR will overlap with the new ETS for buildings and transport. This is not an entirely new phenomenon, given that vehicle CO2 standards, for example, already overlap with the ESR.

The commission explains the reasoning behind the inclusion of these sectors, both of which have seen very slow progress in cutting emissions, in both systems:

“These are sectors where price incentives should be complemented by government action such as tackling market failures, investing in infrastructure, favouring the uptake of zero-emission cars and promoting building renovation. In turn, such policies will enable and facilitate consumers and businesses’ required investment decisions, enhancing cost-effective action and reducing the impact of carbon pricing on individual consumers to the minimum necessary.”

In the run-up to the Fit for 55 launch, NGOs were concerned over the “completely unacceptable” prospect of the ESR being scrapped as emissions trading was expanded to new sectors.

The increased targets were, therefore, broadly welcomed with NGO CAN Europe emphasising the importance of national targets so that governments “take responsibility for climate action”.

Ending aviation and shipping’s exemption from energy taxation

The EU energy taxation directive (ETD) sets minimum rates of excise duty on fuel for transport, heat and electricity. It has not been updated since 2003.

The commission’s proposals for reform argues that the directive is no longer consistent with the bloc’s climate goals – and “de facto favours the consumption of fossil fuel” – thanks to a mixture of low minimum rates combined with member state exemptions and reductions.

These loopholes are “forms of fossil fuel subsidies”, the commission adds, which have “been persistent over the last decade” and amounted to around €40bn in 2016. Notably, the commission wants to end the full exemption currently enjoyed by aviation and shipping.

It also says that the current directive “does not adequately promote greenhouse gas emission reductions, energy efficiency, or alternative fuels”, such as hydrogen or electricity.

The commission is proposing a new structure for the directive, linking tax rates to the energy content and environmental performance of fuels and electricity.

It says “conventional fossil fuels”, including “gas oil” and petrol, would face the “reference” rates of €10.75 per gigajoule (GJ) of energy content for transport uses and €0.9/GJ for heating.

Another category of fossil fuels, including fossil natural gas, would face a transitional rate of tax set at two-thirds of the reference figure for 10 years. The commission says such fuels, “while fossil-based, can still lend some support to decarbonisation in the short and medium term”.

Electricity, “advanced sustainable biofuels” and renewable hydrogen would face the lowest minimum of €0.15/GJ, with other sources of low-carbon hydrogen getting this rate for 10 years.

The commission says “the new system will ensure that the most polluting fuels are taxed the highest” and will raise the minimum rates of duty, which have “never been updated” since 2003.

It is also proposing to end the exemption for passenger aviation and shipping fuel used for journeys within the EU, with minimum duty increasing gradually over 10 years.

As with the proposed inclusion of heat and transport in a parallel EU ETS, there are concerns that reforms to the energy taxation directive could penalise poorer households.

A commission impact assessment, published last year, says any negative social impacts could be offset, if changes to the directive are paired with compensation via social policy and welfare:

“While tax increases for fossil fuels in the transport or heating sector are powerful incentives towards behavioural change, in the short term, consumers may not be easily able to change their consumption patterns when an important share of their income is involved. This will be carefully assessed. The final impact depends on the way in which the redistributive effect is compensated via accompanying measures through social policy and welfare systems.”

As well as social concerns and opposition from industry, there are major procedural hurdles for the commission to overcome if its proposals are to be adopted.

Under EU rules, anything to do with tax is subject to a unanimous vote by member states, with countries including Sweden – and, formerly, the UK – not keen to change this. Individual member states have been able to veto changes to the ETD, scuppering previous attempts at reform,

The commission is attempting to sidestep the need for unanimity by classing the reforms as environmental, rather than a tax matter, meaning only a “qualified majority vote” would be needed.

However, in order to invoke this “passerelle clause” manoeuvre, the commission needs unanimous support from member states, creating something of a “catch 22”.

Aircraft fuel has historically been exempt from the directive, although member states were able to impose duty on domestic flights or under bilateral agreements with other countries.

The Chicago Convention is frequently cited as preventing the taxation of aviation fuel. This line has been taken by UK government ministers, among others, but is incorrect.

A close legal analysis suggests it is a web of some 5,000 international bilateral “air service agreements” between countries that poses a bigger barrier to charging duty on aviation fuel.

As reported in media coverage ahead of the launch, the commission is proposing to impose a minimum rate of duty on aviation fuels that would be phased in over a 10-year period from 2023.

The commission suggests the minimum rate for aviation fuel should, ultimately, reach the same level as for petrol, namely €10.75 per gigajoule (GJ) of energy content.

Contrary to media coverage ahead of the launch, the minimum rate of duty would apply immediately to pleasure and business flights, without a 10-year phase-in.

However, cargo flights and all flights from the EU to international destinations would be exempt. The commission is proposing to implement the UN’s CORSIA scheme for aviation emissions offsets for these flights, if they are operated by airlines based in the EU.

According to Andrew Murphy, aviation director for NGO Transport and Environment, flights within the EU accounted for about two-fifths of total EU aviation emissions prior to the UK’s departure and the coronavirus pandemic. He tells Carbon Brief that the EU-UK aviation deal allows for taxation.

Dan Rutherford, programme director for aviation and shipping at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), tells Carbon Brief that domestic and intra-EU flights will account for about a quarter of the fuel use and CO2 emissions from EU aviation.

(This share is lower due to the large number of cross-channel flights between the UK and continental Europe, Rutherford explains.)

In addition to the energy taxation changes, the commission is proposing two separate initiatives to promote the use of sustainable fuels for aviation and shipping.

Its RefuelEU Aviation initiative would require increasing amounts of “sustainable aviation fuels” (SAFs) to be blended into the mix supplied to aircraft, with the rate rising every five years.

This would start with a 2% minimum in 2025 rising to 5% in 2030, 20% in 2035 and 63% in 2050, with sub-targets for “e-fuels” made from electricity via the use of hydrogen.

Europe’s proposed SAF mandate is out today. Starts with a 2% requirement in 2025 ramping up to 63% in 2050 (!). A few reflections. 🧵 https://t.co/0HoPWgK8iJ pic.twitter.com/SEtSBmg8q1

— Dan Rutherford (@rutherdan) July 14, 2021

Airlines have long touted the potential of SAFs to cut emissions, but usage has been extremely limited. According to the ICCT, uptake of SAF reached just 0.01% of global jet fuel use in 2019 – some 50m litres – due to “strong economic barriers”.

Even within the EU, uptake of SAF reached just 0.05% of jet fuel use prior to the pandemic.

According to Rutherford, the proposed EU targets would, on their own, raise global SAF use 25-fold by 2030 and 400-fold by 2050.

The recent International Energy Agency (IEA) roadmap to net-zero emissions by 2050 included SAF reaching around 15% of global aviation fuel demand by 2030.

Behaviour changes play a small but essential role in our new @IEA #NetZero2050Roadmap. Some may seem radical – and give only small cuts to emissions- but they’re critical where other decarbonisation options are scarce. Here I’ll unpack what they entail & why they’re important… pic.twitter.com/Rbv5BjhXJj

— Daniel Crow (@djgcrow) May 20, 2021

Rutherford also says the €10.75/GJ tax on aviation fuel, compared with the reduced €0.15/GJ for SAF, would help close the price gap between the two.

One concern is that airlines could bypass a fuel tax and SAF rules by “tankering”, whereby they fill up on spare jet fuel before landing in the EU, to minimise the amount they need to buy in the bloc.

This would increase planes’ take-off weight and CO2 emissions, while reducing the amount of mandated SAF sales and EU aviation fuel duty revenue.

The commission proposal aims to prevent this practice by requiring aircraft operators departing EU airports to refuel with as much fuel as they will need to operate their flight.

For shipping, the FuelEU Maritime regulation would set a maximum limit on the greenhouse gas content of energy used by ships calling at EU ports.

NGO Transport and Environment said the proposal “risks locking in fossil gas” and could mean more than half of shipping fuel being gas in 2030.

Finally, an Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation would aim to ensure adequate recharging and refueling infrastructure for the use of electricity, hydrogen and other alternative fuels.

Targeting an end to combustion engine cars

Emissions from road transport account for a fifth of the EU total – the second-largest share behind energy supply – having increased by more than a quarter since 1990.

According to the commission, transport emissions overall – including harder-to-tackle aviation and shipping – need to fall 90% by 2050 to meet the EU’s net-zero target.

The commission has proposed a 55% fleet-wide cut in CO2 emissions from cars and vans sold in the EU by 2030, escalating to a 100% cut by 2035, in an amendment to its previous regulation. Earlier reports had suggested the cut could be even more dramatic – as high as 65% by 2030.

If such measures are implemented, the Financial Times reported ahead of the launch, then 2035 would be the “de facto deadline for the last petrol and diesel cars to be sold in the EU”.

The 2035 date would then leave 15 years for the remaining fleet of fossil-fuelled vehicles to retire and be replaced with electric models in time for the 2050 net-zero date.

The 55% by 2030 goal is a considerable step up from the last time emissions targets were set in 2018 when, after lobbying by manufacturers, a 15% cut by 2025 and 37.5% cut by 2030 were agreed. The sector is critical to the EU economy, accounting for at least 7% of its GDP.

Yesterday’s @EU_Commission proposal sets a new car CO2 target of -55% for 2030 and -100% for 2035. Read my summary and comment in our new @TheICCT blog post: https://t.co/buBbOxxHHJ pic.twitter.com/37Sas98eXp

— Peter Mock (@MockPeter) July 15, 2021

This time around, however, many in the European car industry are already signalling a major shift to electric vehicles in the coming years.

Volkswagen recently announced it would stop selling combustion engines cars in Europe by 2035 and Renault has stated that 90% of its European sales will be electric by 2030.

Volvo has been vocal in calling for a rapid phaseout of combustion engines and for clear direction from the commission on the matter.

According to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), other manufacturers that have recently committed to phase out sales of combustion engine cars in the EU include Audi (by 2033), Fiat and Ford (2030), and Opel (2028).

Support for the shift to EVs is not universal, however. The German carmakers association VDA issued a statement criticising the effective ban on combustion engines, including hybrids, saying consumer choice was being “unnecessarily restricted”. In a statement ahead of the launch it said:

“Restricting the technology to a single drivetrain option within such a short period of time is worrying and does not give any consideration whatsoever to the interests of consumers.”

The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) issued a similar response, saying “banning a single technology is not a rational way forward at this stage”.

Some member states, such as France, are expected to push back against the proposal and call for more flexibility around the inclusion of hybrids in the targets.

Despite this opposition, Prof Simone Tagliapietra, an EU policy expert at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, wrote in a blog post for the thinktank Bruegel that the targets represent a reasonable compromise.

“This proposal is likely to be approved without major turbulence,” he stated.

To support the switch to electric vehicles, another revision – this time to the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation – would require member states to significantly expand charging capacity.

This expansion would require charging and hydrogen fuelling points at intervals on major highways no further than 60km and 150km apart, respectively.

Including land use and forestry in EU targets

The Fit for 55 package includes a proposed update to the rules governing the inclusion of emissions and removals from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) in the EU’s climate framework, known as Regulation 2018/841.

Under the existing regulation, adopted in 2018, member states have to ensure that their LULUCF emissions are balanced by the equivalent volume of CO2 removals between 2021-2030. This is referred to as the “no-debit rule”.

Member states with removals that exceed this obligation can use a limited volume – up to 280m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) across the entire EU – to cancel out emissions from other areas of their economies.

This flexibility has been criticised by some NGOs as it allows carbon removals by trees and land, which are difficult to account for and not always permanent, to offset emissions from fossil fuels.

“We would prefer it if nothing [from LULUCF removals] would count towards the greenhouse gas reduction target, as we consider them not fungible [not equivalent to each other],” Ulriikka Aarnio, senior policy officer at CAN Europe, tells Carbon Brief.

The no-debit rule has also drawn criticism for failing to encourage member states to either increase the size of their carbon sinks or prevent them from reducing in size.

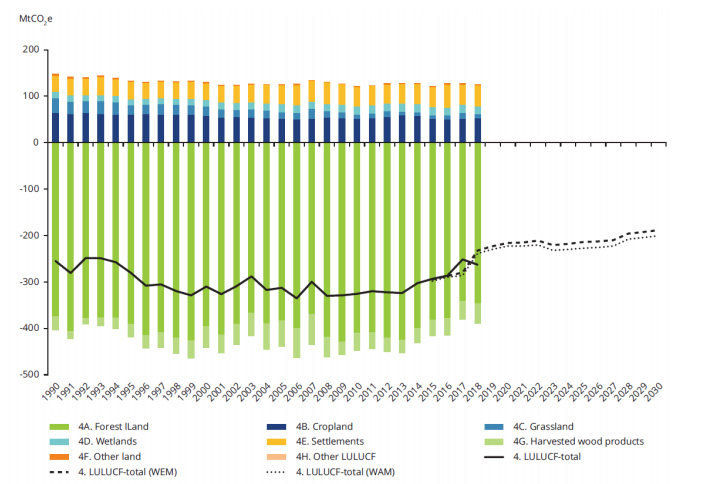

As the chart below shows, there has been a significant decrease in the size of the EU’s overall carbon sink in recent years. This trend is expected to continue and has been attributed to ageing forests, higher tree harvesting rates and climate change-related pressures on forests.

Under the new European climate law, the contribution of LULUCF to the overall 55% emissions reduction target is capped at 225MtCO2e, meaning other sectors must be responsible for at least 53%. This ensures other sectors cannot rely too heavily on removals to offset their emissions.

However, it also means the carbon sink could continue shrinking from its current size of around 265MtCO2e, without the EU and member state targets being missed.

To avoid this, the commission’s new proposals call for an EU target of 310MtCO2e of removals by 2030. This overall target would be further divided up among member states.

Today the European Commission has for the first time proposed a quantitative EU-wide net-removals target of -310 Mt, and translated the EU target into national net-removals targets. This fulfills a pledge made in the negotiation of the EU Climate Law.https://t.co/USl7ECFvCd pic.twitter.com/Lyssexhb3Z

— Andreas Graf (@andreasgraf) July 14, 2021

These annual targets would be “based on the results of a comprehensive review of the reported greenhouse gas inventory” for member states for the years 2021, 2022 and 2023.

Aarnio tells Carbon Brief this shift from the “no debit” system based on “ambiguous forest reference levels” to national targets is “a big positive”.

However, the new overall target of 310MtCO2e removals would only be bringing the sink back up to the level it was around a decade ago.

Environmental groups were critical of the target when it first emerged in a leak, with the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) describing it as “timid”. NGOs have instead called for a much higher LULUCF target of 600MtCOe removals.

From 2031 onwards, the commission has proposed that the regulation would be expanded beyond LULUCF to include non-CO2 emissions from agriculture, meaning methane and nitrous oxide from fertilisers, livestock and other sources.

There are concerns that a lack of specific targets for these non-CO2 emissions means member states could rely on carbon sinks to offset them rather than actually taking steps to cut them.

The new proposals come just weeks after the EU agreed to reform its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), in a move that many saw as insufficient to address a sector responsible for a tenth of the bloc’s emissions.

The new LULUCF regulation would also set a “climate neutrality” objective for EU-wide emissions and removals in these combined sectors by 2035, “generating negative emissions thereafter”.

The document states that, from 2036 onwards, a policy framework “based on a robust carbon removal certification system” could “progressively combine the land sector with other sectors (beyond agriculture) that have exhausted their emissions reduction possibilities, or that have achieved for instance over 90% emission reductions”.

It says that this would provide an incentive to continue increasing carbon removals up until 2050.

Boosting tree-planting with the EU forestry strategy

A few days after the main Fit for 55 package was launched, the commission published its new forest strategy for 2030, including an array of measures to boost tree-planting, encourage better forest monitoring and increase the use of wood products to replace concrete in construction.

It reaffirms the “cascading principle for biomass”, already set out in the previous EU forest strategy.

This says that wood should first be used for long-lived products, such as building materials or furniture, then for extending the life of existing products, followed by re-use and recycling.

Use of wood for bioenergy is ranked fifth in the list of uses and the commission says the use of whole trees and quality roundwood for this purpose should be “minimised”. It also proposes to limit subsidies for bioenergy plants that only generate electricity.

(The UK’s Climate Change Committee has also set out a hierarchy of best uses for biomass, saying the country should “move away” from burning wood for electricity.)

🌲 Forest protection & restoration

— EU Agriculture🌱 (@EUAgri) July 16, 2021

♻️ A sustainable forest bio-economy

🌱 3 billion new trees

These are the key elements of the new #EUForests strategy post 2020 ⤵️

The EU strategy aims to balance the requirements of businesses that rely on harvesting trees with meeting the bloc’s various climate and biodiversity commitments. A leaked draft of the strategy faced strong pushback from parts of the forestry industry.

Although 43% of the EU is covered in forests, there have been concerns about excessive harvesting jeopardising their role as a carbon store. Indeed, the size of the forest carbon sink has shrunk over the past decade (see above).

A report last year by the commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) found that the harvested area of EU forest had increased by nearly 50% between 2016-18.

The authors attributed this to expanding wood markets, including for bioenergy, although the figures have been challenged in another paper which attributed the high figure to “methodological errors”.

The new strategy emphasises that there are:

“Significant opportunities for win-win measures, which simultaneously improve forest productivity, timber production, biodiversity, carbon sink function, healthy soil properties and climate resilience”.

The EU biodiversity strategy included a pledge to plant at least 3bn additional trees across the EU by 2030 “in full respect of ecological principles”.

The forest strategy includes a “roadmap” for the implementation of this target, including the publication of guidelines on “biodiversity-friendly” afforestation by early 2022.

Other components include establishing a “legally binding instrument for ecosystem restoration”, particularly for areas that are well-equipped to absorb carbon, and a “common definition” for primary and old-growth forests, all of which must be strictly protected under the biodiversity strategy.

There are also measures to bolster sustainable forest management and improve the provision of climate-resilient seeds and planting stock.

The strategy also emphasises the importance of encouraging forest managers to increase the area of forest dedicated to “long-lived” wood production, specifically in construction. These wood products can act as a carbon store separate from living forests themselves.

As it stands, this store is around 40MtCO2e each year and there are additional emissions cuts that come from replacing high-emissions building materials with wood. These are estimated to be in the range of 18-43MtCO2e annual savings, the strategy says.

The strategy states that “the most important role of wood products is to help turning the con-

struction sector from a source of greenhouse gas emissions into a carbon sink”.

However, one JRC modelling paper concluded that while increasing tree-harvesting by 20% could boost carbon stored in buildings by 8%, it would cut the significantly larger forest carbon sink by 37% by 2030.

Given this, NGO coalition the Forest Defenders Alliance criticised the “credulity” with which the commission accepted the role of increased harvesting in cutting emissions. “The priority must be protecting, restoring and re-naturalising forests – not increasing harvesting,” it said.

Nevertheless, the commission says in the strategy that it will develop another “roadmap” for reducing lifetime carbon emissions in buildings and a “standard, robust and transparent methodology to quantify the climate benefits of wood construction products and other building materials”.

One proposed method of encouraging landowners to plant trees is through a “carbon farming initiative”, first announced in the EU “Farm to Fork Strategy”, which would reward farmers for climate-friendly practices.

The commission notes that, so far, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has not driven much additional tree-planting, but says there is potential for its new iteration to do so. Many NGOs and scientists have criticised the new CAP for failing to significantly increase support for climate action.

The strategy says the commission will set out an action plan for carbon farming and carbon removal certification by the end of 2021 and is also developing a regulatory framework for certifying carbon removals.

Finally, the commission also says it intends to put forward a new legislative instrument on EU forest planning and monitoring and establish an “EU-wide common digital monitoring framework, using remote sensing technologies”.

A report by Bloomberg highlighted such surveillance measures as a point of contention for “timber merchants wary of stronger restrictions”.

Responding to a leak of the strategy, trade group the Confederation of European Forest Ownerssaid the commission had failed to take views from the sector into consideration and warned any data collected must be corroborated with member states to avoid “misleading information”.