Q&A: What UK’s record auction for offshore wind means for bills and clean power by 2030

Multiple Authors

01.15.26Multiple Authors

15.01.2026 | 2:47pmA record-breaking amount of new offshore wind capacity has been secured at the UK’s latest auction for renewable energy projects.

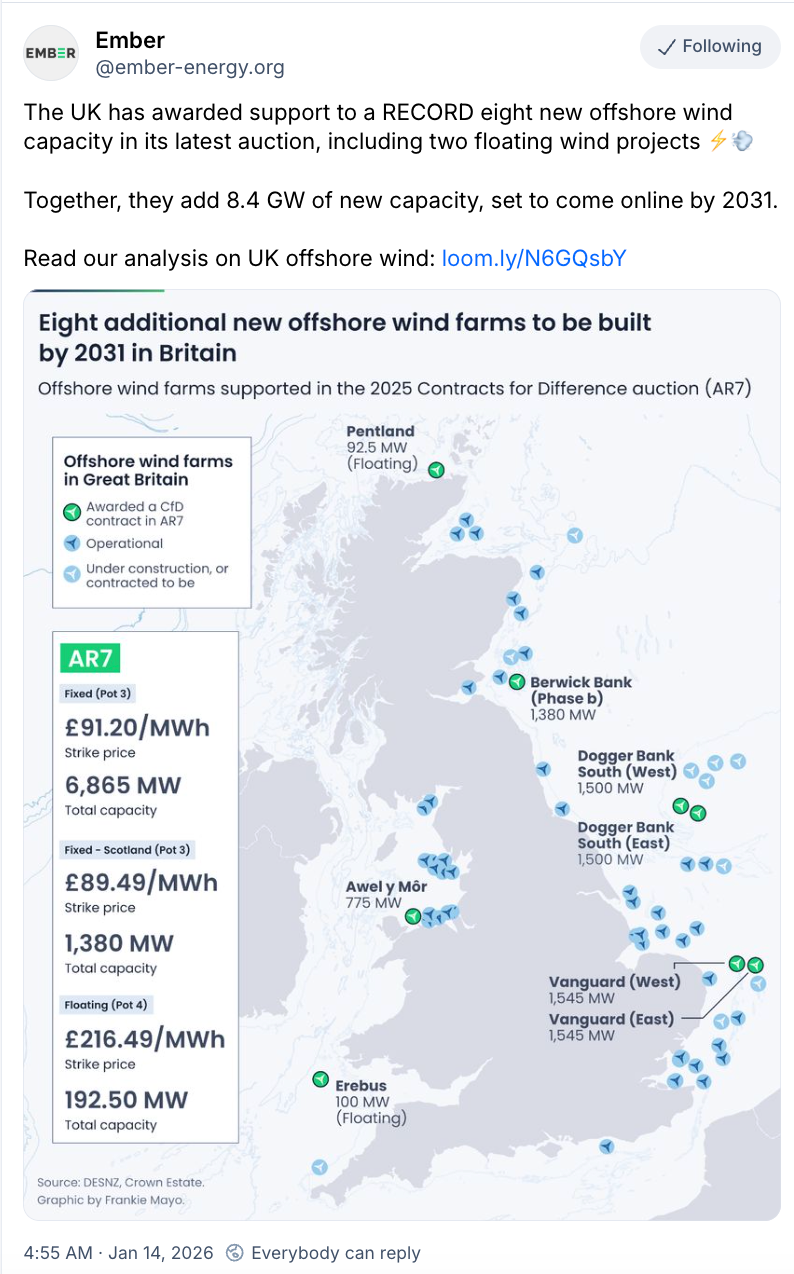

Five fixed-foundation projects, amounting to 8.25 gigawatts (GW), secured fixed-price “contracts for difference” (CfDs) to supply electricity for an average of £91 per megawatt hour (MWh).

Additionally, two floating offshore wind projects with a combined capacity of 192.5 megawatts (MW) won contracts, securing a “strike price” of £216/MWh.

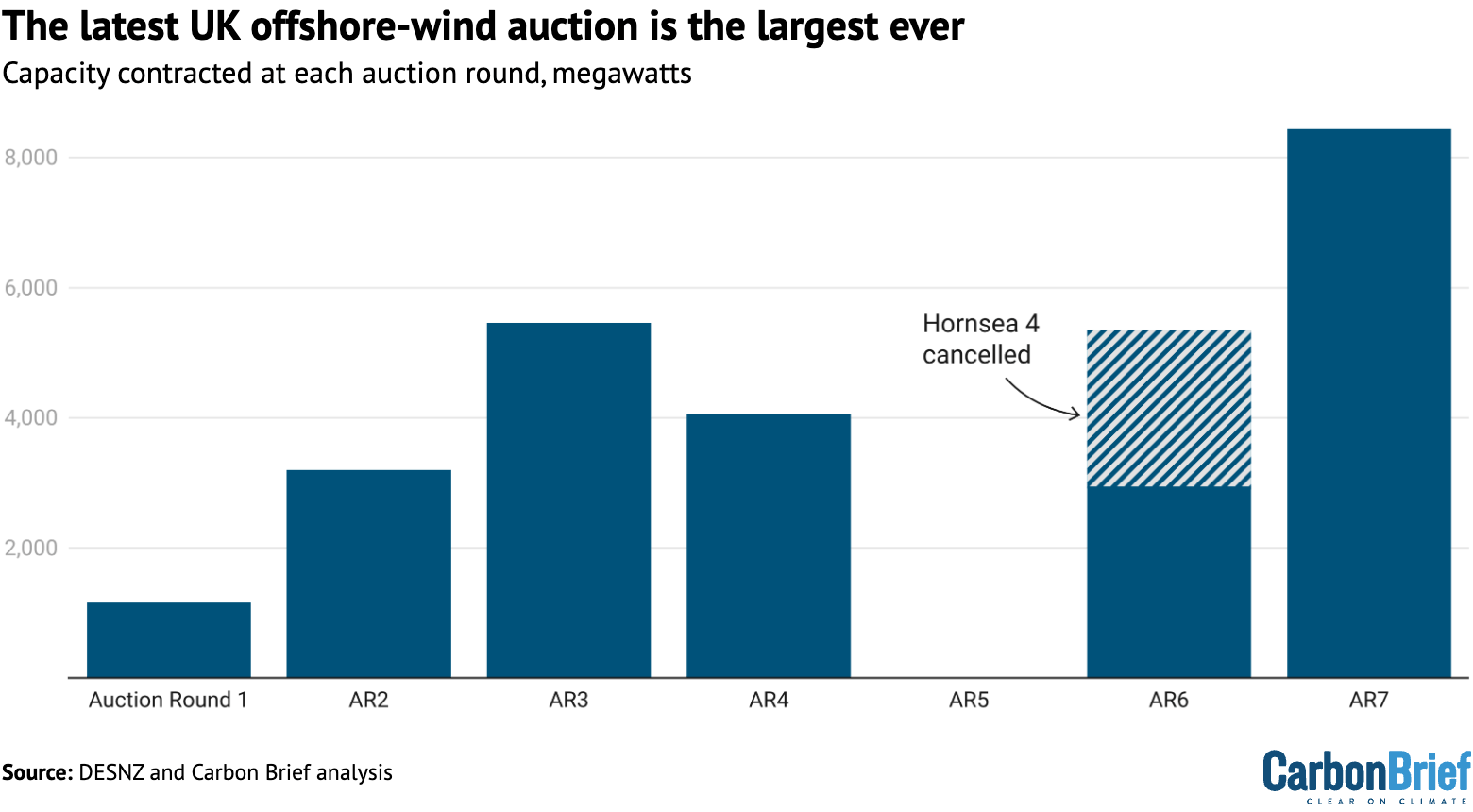

This new capacity, totalling 8.4GW, marks a significant increase from last year’s sixth auction, when 5.3GW had been secured as part of a bounce back from the “failed” fifth round.

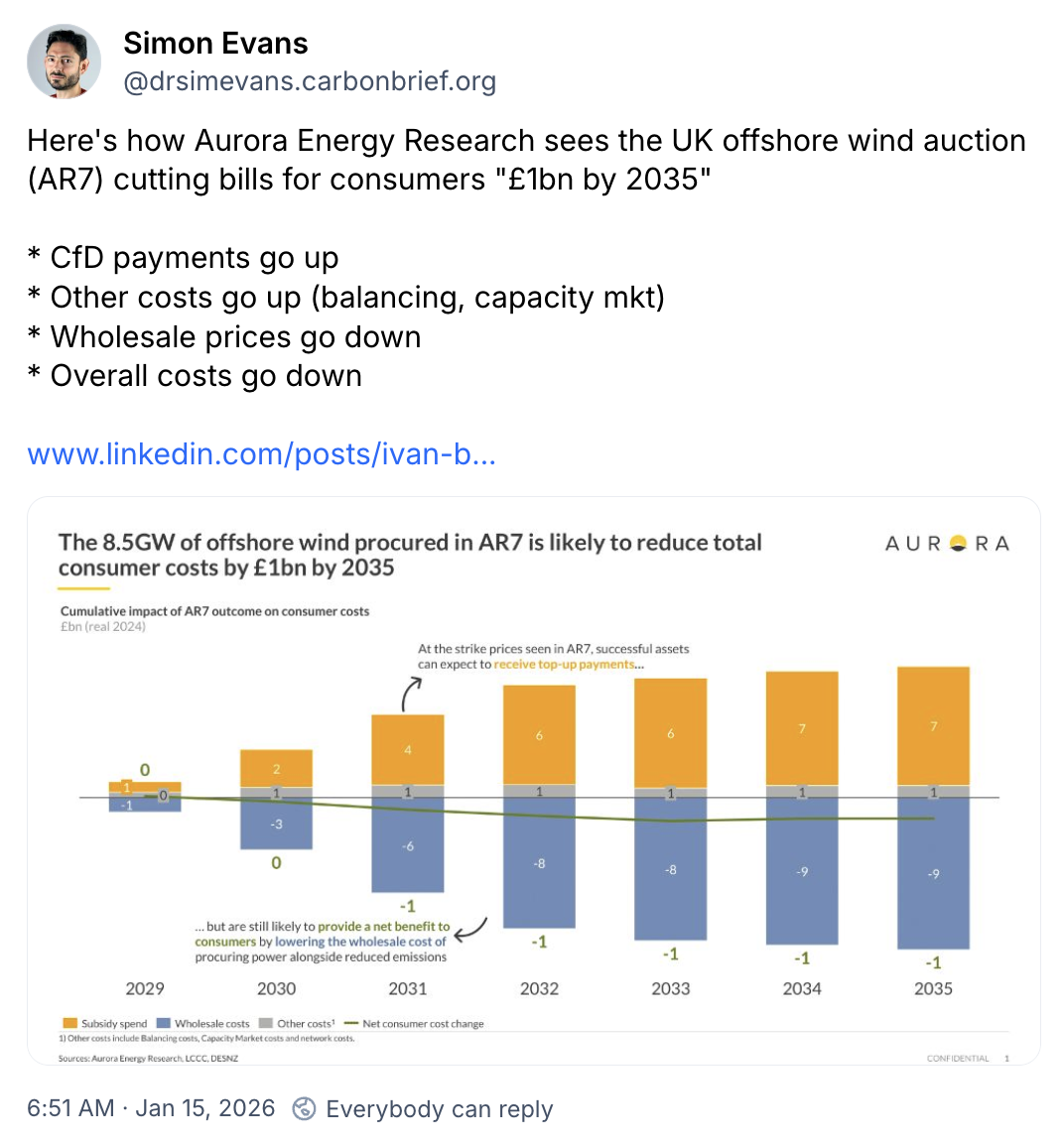

While the latest auction saw offshore wind prices rising by around 10% since the previous round, analysis suggests that the outcome will, nevertheless, be roughly “cost neutral” for consumers.

Contrary to simplistic and misleading comparisons made by some opposition politicians and media commentators, this is because CfD payments would be balanced by lower wholesale costs.

The government welcomed the “stonking” results, saying that it put the country “on track” to reach its 2030 targets for clean power, create jobs and bring new investment.

Below, Carbon Brief looks at the auction results, what they mean for bills and the implications for the UK’s target of “clean power by 2030”.

- What happened in the seventh CfD auction round?

- What does the record offshore-wind auction mean for bills?

- What does AR7 mean for reaching clean power by 2030?

What happened in the seventh CfD auction round (AR7)?

The UK government announced the results of the seventh auction round (AR7) for new CfDs on 14 January 2026, hailing the outcome as a “historic win”.

The CfD scheme was introduced in 2014 and offers fixed-price contracts to generators via a “reverse auction” process. The first auction was held in 2015.

Projects bid to secure contracts to sell electricity at a fixed “strike price” in the future.

If wholesale prices are lower than this set amount, the project receives a payment that makes up the difference.

However, if the market prices are higher than this level, then the project pays back the difference to consumers. For example, according to a report from thinktank Onward, between November 2021 and January 2022, CfD projects paid back £114.4m to consumers.

For the seventh auction round, the results have been split into two, as part of reforms to help expedite the process for offshore wind. As such, the publication of results on 14 January covers fixed-foundation offshore wind and floating offshore wind.

A second set of results will be released between 6-9 February 2026, covering technologies including large-scale solar and onshore wind.

A total of 17 fixed-foundation offshore wind projects totalling 24.8GW of capacity were competing for contracts at this auction, meaning many have missed out.

Still, a record 8.4GW of offshore wind secured contracts, making it the biggest ever offshore wind auction in Europe, according to industry group WindEurope.

This includes 8,245 megawatts (MW) of fixed-foundation offshore wind and 192.5MW of floating offshore wind, which, collectively, will generate enough to power more than 12m homes.

As such, there was an increase of more than 3GW in offshore wind capacity compared to the sixth allocation round, as shown in the chart below.

(The 2.4GW Hornsea 4 scheme, which had been awarded a CfD at the previous auction round, went on to be cancelled in May 2025, with developer Ørsted citing cost inflation.)

This follows on from the “fiasco” of the fifth allocation round in 2023, where no offshore-wind projects secured contracts due to the limit on prices set by the government.

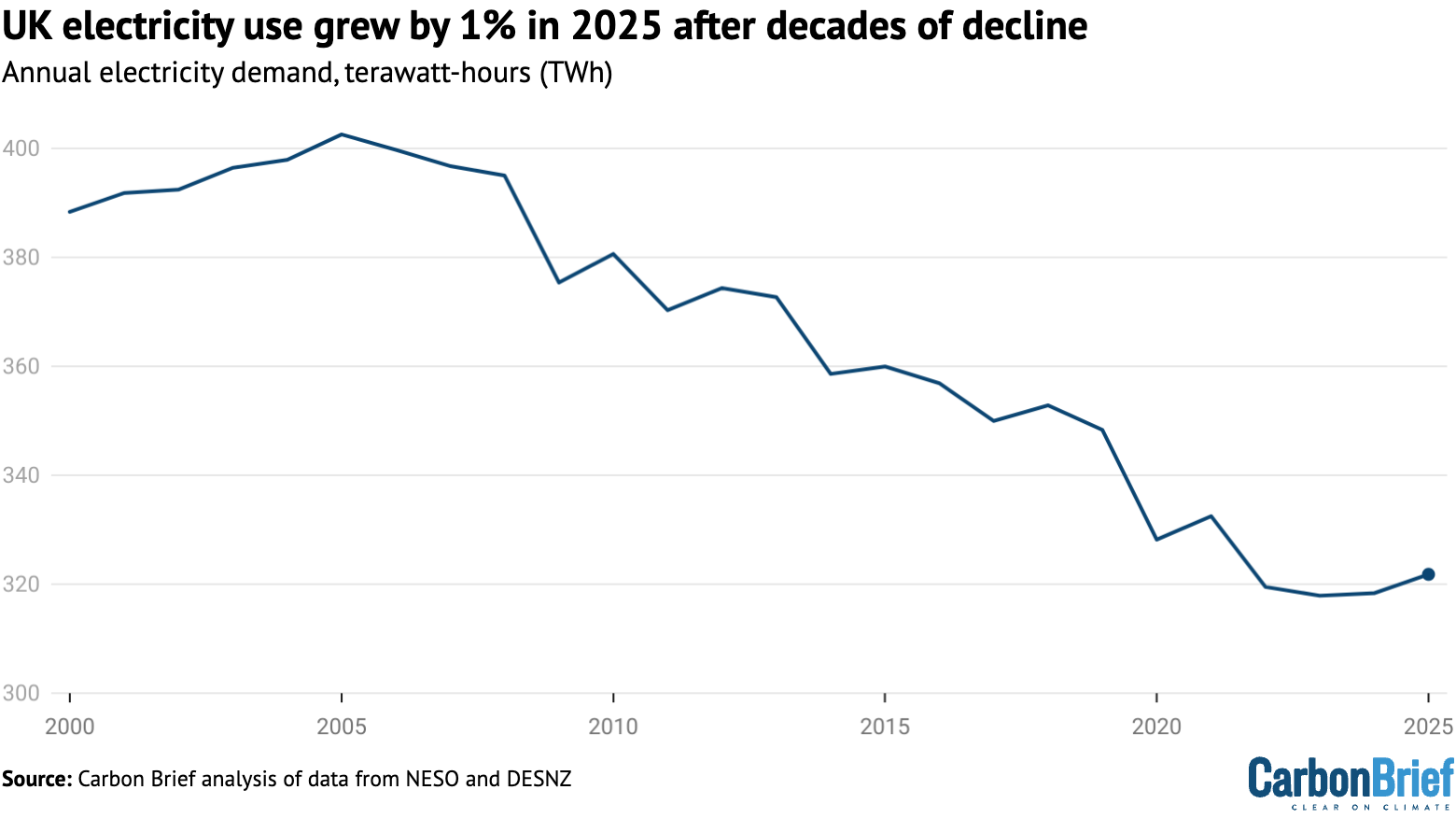

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that the capacity secured in the latest auction will generate around 37 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity each year, around 12% of the nation’s total demand.

With onshore wind and solar results still to come, this means that projects with CfDs will generate some 135TWh of power by the time they are all completed, or nearly half of current demand.

When the current Labour government took office in 2024, a number of changes were made to encourage offshore wind capacity bids. This included separating the technology from solar and onshore wind into a separate “pot”, an allowance for “permitted reduction” projects in AR6 and a significant increase to the “budget” for the auction overall.

Since then, there have been continued reforms to help meet the government’s target of decarbonising power supplies by 2030. (See: What does AR7 mean for clean power by 2030.)

This includes extending the contracts from 15 years to 20 years, relaxing eligibility requirements related to planning consent and legislating to allow the secretary of state for energy – currently, Ed Miliband – to see anonymised bid information ahead of setting a final budget for that technology.

Initially, the government set a total budget of £900m for fixed-foundation offshore wind projects and £180m for floating offshore wind.

The budget for fixed-foundation offshore wind projects was then raised to £1,790m.

(Note that the “budget” is a notional limit on the amount of CfD levies that can be added to consumer electricity bills. This does not come from government coffers and – as explained below – it does not translate into an equivalent increase in consumer costs, because CfD projects also reduce wholesale electricity prices, which make up the bulk of bills.)

Ahead of the auction, the maximum “administrative” strike price was set at £113/MWh for offshore wind and £271/MWh for floating offshore wind.

The four winning fixed-foundation offshore wind projects in England and Wales secured a strike price of £91.20/MWh in 2024 prices and the one in Scotland £89.49/MWh, as shown in the table below. This comes out at a blended average of £90.91/MWh.

| Projects (fixed-foundation) | Capacity (MW) | Owners | Strike price (2024 prices) | Delivery year (phase one) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awel y Mor | 775 | RWE, SWM, Siemens Financial Services | £91.20/MWh | 2030/31 |

| Dogger Bank South | 3,000 | RWE, Masdar | £91.20/MWh | 2030/2031 |

| Norfolk Vanguard East | 1,545 | RWE | £91.20/MWh | 2029/2030 |

| Norfolk Vanguard West | 1,545 | RWE | £91.20/MWh | 2028/2029 |

| Berwick Bank | 1,380 | SSE Renewables | £89.49/MWh | 2030/2031 |

The two floating offshore-wind projects will see a strike price of £216.46/MWh, shown below.

| Projects (floating) | Capacity | Owners | Strike price (2024 prices) | Delivery year (phase one) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentland | 92.5 | CIP, Eurus Energy, Hexicon | £216.46/MWh | 2029/2030 |

| Erebus | 100 | TotalEnergies, Simply Blue Energy | £216.46/MWh | 2029/2030 |

These prices are around 19% below the maximum level set ahead of the auction – a figure that had been cited by opposition politicians as “proof” that the round would be a “bad deal” for consumers.

Successful projects include RWE’s Awel Y Mor (775MW), the first Welsh project to win a CfD contract in more than a decade.

Dogger Bank South in Yorkshire and Norfolk Vanguard in East Anglia – which will be two of the largest offshore windfarms in the world – at 3GW and 3.1GW, respectively – both secured contracts.

Additionally, Berwick Bank in the North Sea became the first new Scottish project to win a CfD since 2022. At 4.1GW, the project being developed by SSE Renewables is the largest planned offshore-wind project in the world.

The projects are located around the UK, which is expected to ease grid connections. Nick Civetta, project leader at Aurora Energy Research, noted in a statement:

“83% of the capacity connects in areas of high power demand and greater network capacity, lowering the cost of managing the system.”

In terms of companies, German developer RWE has dominated the auction outcome, with 6.9GW of the capacity being developed overall.

What does the record offshore-wind auction mean for bills?

The auction results arrive at a moment of intense interest in energy bills, which remain significantly higher than before the global energy crisis in 2022.

The government, along with much of the energy industry, said the new offshore wind projects would lower bills, relative to the alternative of relying on more gas.

Meanwhile opposition politicians and right-leaning media used misleading figures to argue that gas power is cheap or that the new offshore wind projects would add large costs to bills.

Broadly speaking, there is some evidence to suggest that electricity bills will rise over the years to 2030 – largely as a result of investment in the grid – before starting to decline.

However, this is the case whether the UK pushes forward with its efforts to expand clean power or not – and is mainly dependent on the timing of electricity network investments and the price of gas.

At the same time, electricity demand is starting to rise as the economy electrifies – as shown in the figure below – and many of the UK’s existing power plants are nearing the end of their lives.

This means that new electricity generation will be needed, whether from offshore wind, gas-fired power stations or from other sources.

Adam Berman, director of policy and advocacy at industry group Energy UK, said ahead of the auction that renewables were the “cheapest” source of new supplies.

Similarly, Pranav Menon, senior associate at consultancy Aurora Energy Research, tells Carbon Brief that the key question is how to meet rising demand most cost-effectively. He says:

“Here, it is quite clear that the answer is renewables (up to a certain price and volume), given that new-build gas is much more expensive…(even after accounting for costs and intermittency for renewables).”

The government said that the price for offshore wind secured through AR7 was “40% lower than the cost of building and operating a new gas power plant”. It added:

“Britain has taken a monumental step towards ending the country’s reliance on volatile fossil fuels and lowering bills for good, by delivering a record-breaking offshore wind result in its latest renewables auction.”

In a similar vein, Dhara Vyas, head of Energy UK said in a statement that the results would “deliver lower bills”. She added:

“Today’s auction results will deliver critical national infrastructure that will strengthen our energy security and deliver lower bills, as well as provide jobs, investment and economic growth right across Great Britain.”

These statements rely on updated government estimates of the cost of different electricity-generating technologies, published alongside the auction results.

They also rely on two studies published by Aurora and another consultancy, Baringa, both commissioned by renewable energy firms involved in the auction.

The government’s new cost estimates reflect the inflationary pressures that have hit turbines for gas-fired generation, as well as offshore wind supply chains.

Carbon Brief analysis of the latest and previous figures suggests that the government thinks the cost of building a gas-fired power station has more than doubled. (Reports from the US point to even steeper three-fold increases in gas turbine costs.)

As such, building and operating new gas-fired power stations would be relatively expensive, at £147/MWh, according to the government. (This assumes the gas plant would only be operating during 30% of hours in each year, in line with the current UK fleet.)

While the offshore wind prices secured in AR7 are around 10% higher than in AR6, at £91/MWh, they would still be considerably lower than the cost of a new gas plant.

However, these figures for new gas and for offshore wind in AR7 do not reflect the wider system costs of keeping the electricity grid running at all times.

In late 2025, Baringa concluded that a strike price of up to £94.50/MWh for up to 8GW of offshore wind would be “cost neutral”. This does not include system balancing costs, which the study argues are relatively modest for each additional gigawatt of capacity.

Carbon Brief understands that, when taking this into account, the “cost neutral” price for further offshore capacity would be reduced by a few pounds. This implies that the AR7 result at £91/MWh is likely to be in or around the “cost-neutral” range, based on Baringa’s assumptions.

Also, in late 2025, Aurora concluded that new offshore wind could be secured at “no net cost to consumers”, provided that contracts were agreed at no more than £94/MWh.

In contrast to Baringa’s work, this study is based on what an Aurora press release describes as a “total system cost analysis”. This means it takes into account the cost of dealing with the variable output of offshore wind, such as system balancing and backup.

In an updated note following the results of the auction, Aurora said that it would “generate net consumer savings of just over £1bn up to 2035”. This is relative to a scenario where no offshore wind had been procured at the latest auction.

(In its pre-auction analysis, Aurora pointed to a reduction in consumer electricity bills of around £20 per household per year by 2035, relative to relying on more gas power instead.)

Writing on LinkedIn, Aurora data analyst Ivan Bogachev said that this was the case, even though it might appear to be “counterintuitive”. He added:

“Moreover, AR7 projects are primarily clustered in areas which see few network constraints, limiting any contribution to higher balancing costs.”

In contrast, Conservative shadow energy secretary Claire Coutinho and right-leaning media commentators cited misleading figures to claim that the auction was “locking us in” to high prices.

Coutinho has repeatedly cited a figure for the cost of fuel needed to run a gas-fired power station in summer 2025 – some £55/MWh – as if this is a fair reflection of the cost of electricity from gas.

However, this excludes the cost of carbon, which gas plants must pay under the UK emissions trading system and the “carbon price support”. It also ignores the cost of building new gas-fired capacity, which as noted above has soared in recent years.

Dr Callum McIver, a researcher at the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) and research fellow at the University of Strathclyde, tells Carbon Brief that “you can’t credibly strip out the cost of carbon” and that the £55/MWh figure is not an “apples-to-apples” comparison with the AR7 result.

McIver says that a fairer comparison would be with a new-build gas plant, which, according to the latest DESNZ cost of generation report, would come in at £147/MWh – and would remain at £104/MWh, even if the cost of carbon is ignored.

UKERC director Prof Robert Gross, at Imperial College London, tells Carbon Brief that Coutinho’s £55/MWh figure for gas is “unrealistically low” because it is below current wholesale prices, which averaged around £80/MWh in 2025.

Gross adds that, as well as ignoring carbon pricing, the figure is also for “existing and not new gas stations, which we will need and which will need to recover much increased CAPEX [capital cost]”.

Another factor often not taken into account by those criticising the price of renewable energy contracts is that these projects reduce wholesale prices, as noted in Aurora’s modelling.

Separate analysis published by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) thinktank finds that wholesale power prices would have been 46% higher in 2025 – at £121/MWh rather than £83/MWh – if there had been no windfarms generating electricity.

This is because windfarms push the most expensive gas plants off the system, reducing average wholesale prices. This is a well-known phenomenon known as the “merit order effect”.

What does AR7 mean for reaching clean power by 2030?

Offshore wind is expected to be the backbone of the UK’s electricity mix in 2030, making the stakes for this CfD auction particularly high.

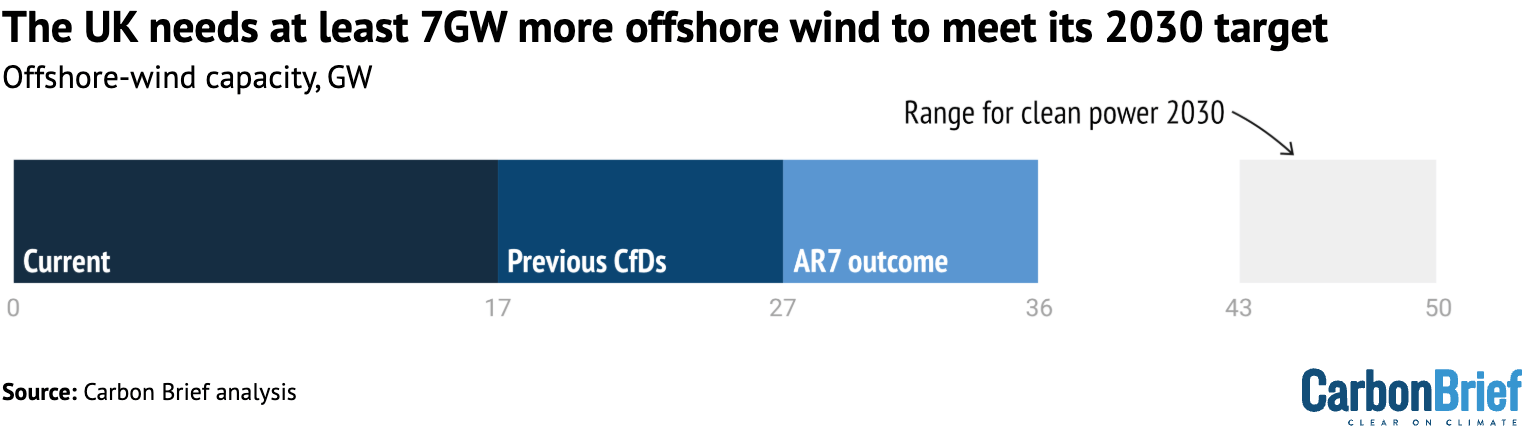

Under the National Energy System Operator’s (NESO) independent advice to the government, half of electricity demand will be met by offshore wind by 2030. It says this requires between 43GW and 51GW of generating capacity from the technology.

This advice informed the government’s action plan for meeting 100% of electricity demand with clean power by the end of the decade, which also sets a target of 43-50GW of offshore wind.

Currently, the UK has around 17GW of installed offshore wind capacity, leaving a gap of 27-34GW to the government’s target range.

A further 10GW of capacity already had a CfD prior to the latest auction, excluding the cancelled Hornsea 4 project. The additional 8.4GW contracted in AR7 means the remaining gap to the minimum 43GW end of the government’s range is just 7GW, as shown below.

Speaking to journalists after the auction results were announced, Chris Stark, who is head of “Mission Control” for clean power 2030, told journalists that securing 8.4GW in AR7 put the UK on track for its targets. He added:

“The result today actually takes us now to within touching distance of the goals that we set for 2030 – more to come on that, as I mentioned, with the onshore technologies and the storage projects up and down this country.

“But this is, I think, a real endorsement for the steps that Ed Miliband has taken to bring about that goal of clean power by 2030, it will bring huge benefits to people here in the UK.”

There remain a number of challenges with the delivery of these offshore-wind projects – including securing a grid connection – that could threaten delivery before 2030.

Writing on LinkedIn, Bertalan Gyenes, consultant at LCP Delta, says that with a third of the new capacity set to deliver before 2030, a “swiftly delivered and ambitious [allocation round eight] would put DESNZ within touching distance of its targets”. However, he adds:

“The job is not over yet, the windfarms need to be connected, the network upgraded, consenting pipelines de-clogged – there can be no more delays and certainly no cancellations like what we had seen with Hornsea 4 after last year’s auction.”

McIver wrote on LinkedIn that the auction result “takes us into the goldilocks zone that just about keeps CP30 targets alive, if AR8 can similarly deliver”. He added:

“OK, looking at delivery years [for the contracted projects], maybe we’re aiming for roughly CP33 [clean power by 2033] now? Maybe that would be no bad thing.”

Within the briefing for journalists, Stark highlighted a number of steps undertaken by the government over the past 18 months to ease the challenges around the expansion of the renewable energy sector.

This includes removing “zombie projects” from the queue for connecting projects to the electricity network and announcing £28bn in investment for gas and electricity grids.

As such, the auction results fit within a “host of policies” designed to make the ambitious clean power by 2030 target possible, said Stark.

The second half of the CfD results, covering technologies such as onshore wind and solar, are expected out next month. DESNZ’s action plan set a range of 27-29GW and 45-47GW of capacity for the two technologies, respectively, if the country is to meet its 2030 clean-power target.