UK budget 2025: Key climate and energy announcements

Multiple Authors

11.26.25UK chancellor Rachel Reeves has announced new measures to cut energy bills alongside a “pay-per-mile” electric-vehicle levy as part of Labour’s second budget.

The policy changes are expected to cut typical household bills by around £134 per year, amid intense political scrutiny of energy prices and a government pledge to reduce them.

This cut is achieved through a combination of moving a portion of renewable-energy subsidies from bills to general taxation and ending a support scheme for energy-efficiency measures.

Reeves has also retained a long-standing freeze on fuel-duty rates on petrol and diesel, albeit with a plan to “gradually” reverse the extra cuts introduced under the previous government.

With fuel-duty receipts set to fall as people opt for electric vehicles, the government has also laid out its plan for an “electric vehicle excise duty” from 2028, to replace lost revenue.

The government has also announced new “transitional energy certificates” to allow new oil and gas production at or nearby to existing sites, as part of its plan for the future of the North Sea.

Below, Carbon Brief runs through the key climate- and energy-focused announcements from the budget.

- Energy bills

- Electric vehicles

- Fuel duty

- North Sea oil and gas

- Nuclear, ‘green finance’, critical minerals and rail

Energy bills

The chancellor used her budget speech to announce two major changes that will cut dual-fuel energy bills for the average household by £134 per year from April 2026.

The first is to bring the “energy company obligation” (ECO) to an end, once its current programme of work wraps up at the end of the financial year. This will cut bills by £63 per year, according to Carbon Brief analysis of the forthcoming energy price cap, which will apply from 1 January 2026.

The second is for the Treasury to cover three-quarters of the cost of the “renewables obligation” (RO) for households, for three years from April 2026. This will cut bills by £70 per year.

The total impact for typical households – those using gas and electricity – will be to cut bills by an average of £134 per year over the three-year period to April 2029.

(As explained in footnote 77 of the budget “red book”, this rises to an average of £154 per year, when including households that use electric heating and are not connected to the gas grid. This figure is then rounded to £150 per year in government communications around the budget.)

Notably, given the political attention on energy prices, this three-year period of discounted bills runs through to just before the next general election, which must be held by August 2029.

There has been furious debate over the past year over the causes and the most effective solutions to the UK’s high energy bills. A Carbon Brief factcheck published earlier this year showed that it was high gas prices, rather than net-zero policies, which has been keeping bills high.

Nevertheless, a politicised debate has continued and there has also been increasing attention on the factors that will put pressure on bills in the near future, such as efforts to strengthen the electricity grid.

At the same time, the advisory Climate Change Committee (CCC) has repeatedly advised the government that it should make electricity cheaper, as so much of the UK’s climate strategy depends on getting homes and businesses to use electricity for heat and transport.

The changes in the budget will go some way to addressing this.

Carbon Brief calculations show that they would cut unit prices for domestic electricity users by around 4p per kilowatt hour (kWh) – roughly 16% – from 28p/kWh under the next price-cap period from the start of 2026, down to around 23p/kWh.

However, the red book says the government wants to further “improve” the price of electricity relative to gas, often referred to as “rebalancing”. It explains:

“The government is committed to doing more to reduce electricity costs for all households and improve the price of electricity relative to gas…The government will set out how it intends to deliver this through the ‘warm homes plan’.”

Under ECO, which has been in place since 2013, utility firms must install energy efficiency measures in fuel-poor homes, funded by a levy on energy bills.

It replaced two earlier schemes, known as CERT and CESP, with reduced funding after then-prime minister David Cameron reportedly told ministers to “get rid of the green crap”. This shift coincided with a precipitous decline in the number of homes being treated with new efficiency measures.

The ECO scheme has been hit by a series of scandals, with a recent National Audit Office report citing “clear failures” in its design, resulting in “widespread issues with the quality of installations”.

Pre-budget media reports had speculated that the government would pay for ongoing energy efficiency initiatives after scrapping ECO, using funding from the forthcoming “warm homes plan”. This speculation had suggested that subsidies for heat pumps would be cut as a result.

Instead, the budget includes an extra £1.5bn of funding for the warm homes plan, to cover the additional cost of taking over from ECO. (The total cost of ECO was around £1.7bn.)

Adam Bell, head of policy at the consultancy group Stonehaven and the government’s former head of energy policy, tells Carbon Brief that, while this £1.5bn is not the total cost of ECO, the scheme had been “terribly inefficient”. He adds that a government-run alternative that tackles home upgrades on an area-by-area basis was “likely to be cheaper”.

Contrary to much pre-budget speculation in the media, the chancellor did not reduce the already-discounted 5% rate of VAT on energy bills. Nor did she scrap the “carbon price support”, a top-up carbon tax on electricity generators.

Finally, the budget red book says that the government “recently confirmed” an increase in the level of relief for certain industrial users, from electricity network charges.

It says that, in total from 2027, the “British industrial competitiveness scheme” will cut electricity costs for affected businesses by £35-40 per megawatt hour.

Electric vehicles

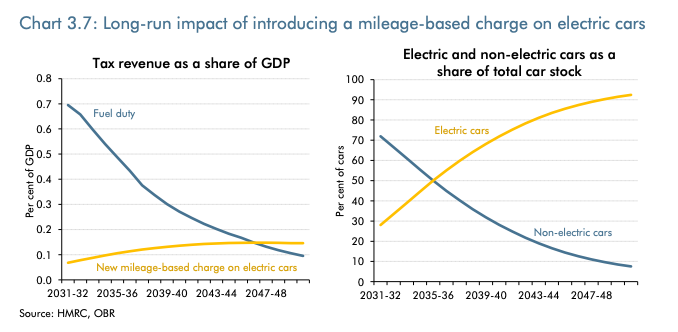

The budget confirmed the introduction of a new “pay-per-mile” charge for electric vehicles, to raise more than £1bn in additional tax revenue by the end of this decade.

It has long been expected that fuel-duty receipts will begin to fall as electric vehicles start making up a rising share of cars on the road.

In its report accompanying the budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts a decline to around half of current levels in the 2030s in real terms, before falling to near-zero by 2050.

As such, the new charge on EVs will help maintain road infrastructure, the budget states. The “red book” notes that the new tax will see EV drivers paying a “fair share”. It adds:

“All vehicles contribute to congestion and wear and tear on the roads, but drivers of petrol and diesel vehicles pay fuel duty at the pump to contribute their fair share, whereas drivers of electric vehicles do not currently pay an equivalent.”

The electric vehicle excise duty (eVED) will come into effect in April 2028 at a rate of 3p per mile for battery electric vehicles and 1.5p per mile for plug-in hybrid cars, according to the OBR report.

The budget red book says this will mean the average driver of a battery electric vehicle paying “around £240 per year”. This is roughly half of the rate of fuel duty paid per mile by petrol and diesel car owners. (See: Fuel duty.)

(EVs will remain significantly cheaper to run than their combustion-engine equivalents. According to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit thinktank, EVs would still be £1,000 cheaper to run per year than petrol equivalents, even after the new eVED charge.)

Currently, there is no equivalent to fuel duty for electric vehicles. Excise duty was brought in for EVs for the first time in April 2025, costing £10 for the first year and then rising to a standard rate of £195 per year – an increase announced in last year’s budget.

The introduction of the eVED is expected to raise £1.1bn in 2028-29 and £1.9bn in 2030-31, dependent on electric-vehicle uptake in the coming years.

The revenue generated by the eVED will “support investment in maintaining and improving the condition of roads”, the budget adds, with the government committing to £2bn in annual investment by 2029-30 for local authorities to repair and renew roads.

A consultation will be published seeking views on the implementation of eVED, the budget notes. It adds that there will be no requirement to report where or when the miles are driven, or to install trackers in cars.

The OBR report states that the additional charge of the eVED “is likely” to reduce demand for electric cars, due to increasing their lifetime costs.

Overall, it estimates that there will be around 440,000 fewer electric car sales across the forecast period relative to its previous forecast.

New support for EV buyers and manufacturers also announced in the budget could help offset 130,000 of this impact, the report notes.

This includes a boost to the electric car grant, which was launched in July and currently offers up to £3,750 off eligible vehicles.

The budget announces an increase of £1.3bn in funding for the programme, as well as an extension out to 2029-30.

Additional measures include an increase in the threshold at which EV owners have to pay the “expensive car supplement” from £40,000 to £50,000 from April 2026. This is expected to cost the government £0.5bn in 2030-31, the OBR notes.

The government will delay changes to “benefit-in-kind” (BIK) rules for employee car-ownership schemes until April 2030. This is a continuation of a policy announced in Reeve’s first budget as chancellor in 2024, which delayed the previously planned increase in BIK rates to 9% per year for electric vehicles by 2029, instead increasing them to just 2% per year out to 2029-30.

EV manufacturers will see the research and innovation Drive35 programme extended, with a further £1.5bn allocated to the project to 2035. This takes total funding for the project to £4bn over the next 10 years, according to the government.

Beyond the vehicles, the budget includes investment for EV charging infrastructure – also partly funded through the eVED revenues, it notes – with an additional £100m allocated. This builds on the £400m announced in the spending review in June.

Additionally, funding will be allocated to local authorities to support the rollout of public chargepoints, a consultation will be launched on permitting rights for cross-pavement EV charging and a 10-year 100% business-rates relief for eligible EV chargepoints will be introduced.

Fuel duty

Former Conservative governments repeatedly cancelled inflation-linked increases in fuel duty – a tax paid on petrol and diesel – every year since 2010.

Fuel duty was cut by an additional 5p per litre in 2022 by then-Conservative chancellor Rishi Sunak in response to the energy crisis.

Successive freezes in fuel duty have substantially increased the UK’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by lowering the cost of driving and, therefore, encouraging people to use their cars more and low-carbon transport options less.

Last year, Reeves opted to maintain the existing freezes and cuts introduced by her predecessors.

In the new autumn budget, she has once again announced a freeze on fuel-duty rates for an additional five months from April until September 2026.

Beyond that, the government says the 5p additional cut introduced in 2022 will be reversed – “gradually returning to March 2022 levels by March 2027”. However, the planned increase in fuel-duty rates in line with inflation for 2026-27 will be cancelled.

Then, from April 2027 onwards, the government says that fuel-duty rates will increase annually to reflect inflation.

In total, the 16 years of delays to expected increases in fuel duty rates – plus the “temporary” 5p cut – will have cost the Treasury £120bn by 2026-27, compared to the expected rise in line with inflation from 2010 onwards, according to the OBR.

Increasing fuel duty is very unpopular. However, research by the Social Market Foundation thinktank suggests persistent freezes have “done little for average Brits”, with the wealthiest in the country disproportionately benefiting.

Meanwhile, the government is also responding to the long-term decline in fuel-duty receipts “as more people choose to switch to cleaner, greener electric cars” by introducing a new per-mile charge on electric-vehicle use from 2028. (See: Electric vehicles.)

North Sea oil and gas

Much of the environmentally focused coverage previewing the budget centred on government plans to allow for new oil and gas production on or near existing field sites in the North Sea.

This was formally announced in the North Sea future plan, a 127-page document outlining the government’s approach to put the region “at the heart of Britain’s clean energy and industrial future” and “deliver the next generation of good, new jobs”.

(The plan was published in response to a consultation held earlier this year on the North Sea’s future, involving nearly 1,000 responses from stakeholders, including oil and gas companies and environmental groups.)

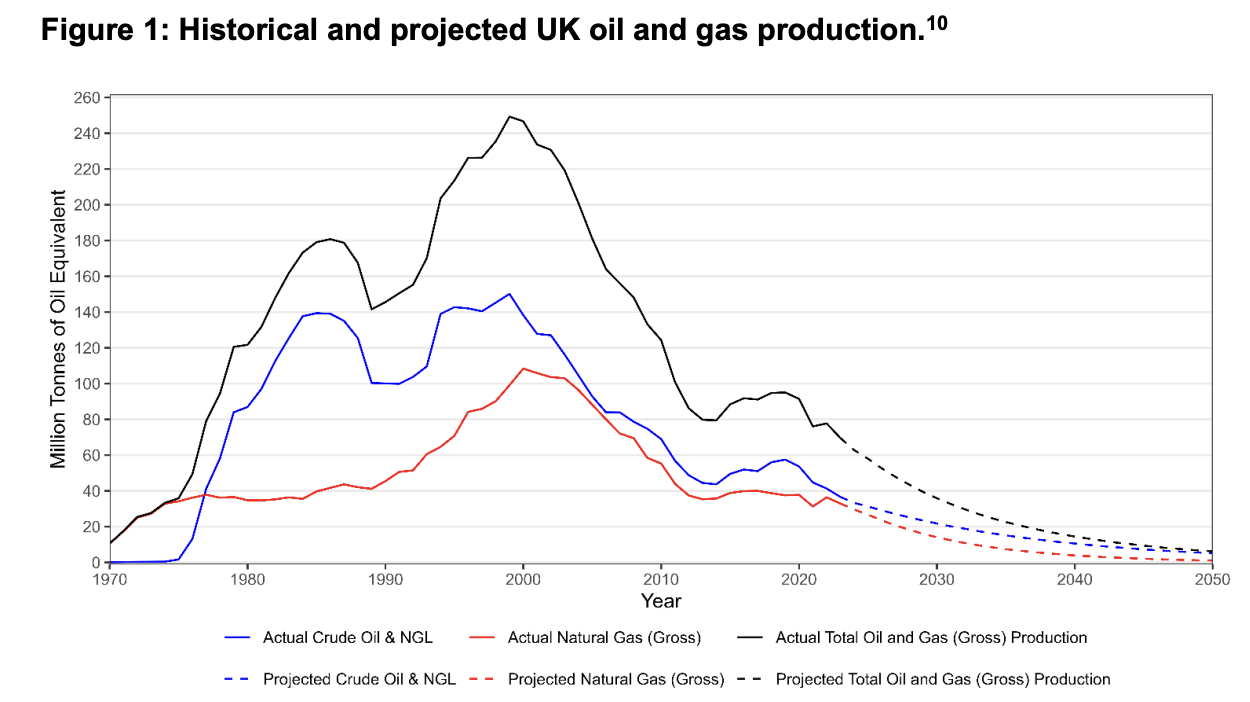

The future plan outlines that the North Sea is an ageing oil and gas basin, “much more so than other areas of the world”, and that production has been “naturally declining over the past 25 years”.

It includes the chart below, showing past and projected oil and gas production.

It adds that the decline of the basin caused direct jobs in oil and gas production to fall by a third between 2014 and 2023, according to official statistics.

The plan also has a section on the UK’s “proud history” of international climate leadership.

It notes that the UK is committed to the Paris Agreement, which has the aim to keep global warming to well-below 2C, while pursuing efforts to keep it at 1.5C, by the end of the century.

It continues:

“Scientific evidence from the International Energy Agency, UN Environment Programme and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that new fossil fuel exploration risks exceeding the 1.5C threshold. The IPCC warns that emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure alone could surpass the remaining global carbon budget, reinforcing the urgency to phase out fossil fuels.”

The plan says that the UK “now has the opportunity to lead in clean energy”, which “is both a national and global imperative”.

With this backdrop, the plan reaffirms Labour’s manifesto commitment to not issue any new oil and gas licences.

However, the plan says that the government will introduce “transitional energy certificates” to allow new oil and gas drilling on or near to existing fields, as long as this additional production does not require exploration.

An analysis by the North Sea transition charity Uplift found that the amount of oil and gas that could be produced by such certificates is “relatively small”.

It suggested that new discoveries within a 50km radius of existing productions contain just 25m barrels of oil and 20m barrels of oil equivalent of gas.

(By comparison, the Rosebank oil field, which is currently seeking development consent from the government, would produce nearly 500m barrels of oil and gas equivalent in its lifetime.)

In a footnote on page 36, the plan says that these certificates will have no effect on the process for giving development consent to new oil and gas projects.

Last year, Carbon Brief reported that several large oil and gas projects are currently seeking development consent from the government.

Because they already have a license, these projects are able to get around Labour’s policy on not issuing any new oil and gas licenses and still seek final approval.

However, a landmark legal case in 2024 means that all of such projects, including Rosebank, will now have to present the government with information about how much emissions will come from burning the oil and gas they plan to produce, before they can be approved.

Responding to today’s budget news, Tessa Khan, executive director of Uplift, said that the “government is right to end the fiction of endless drilling”, but should “put an end to all new fields, including the huge Rosebank oil field”.

The North Sea future plan also says that the government will change the objectives of the North Sea Transition Authority, the government-run company that controls and regulates offshore oil and gas production.

Before the change, the NSTA was in the awkward position of being responsible for both ensuring the oil and gas sector reaches net-zero and maximising the economic recovery of oil and gas reserves from the North Sea.

Now, the government wants the NSTA to balance three objectives: to “maximise societal economic value”; support the energy secretary in meeting net-zero goals; and consider the long-term benefits of the transition for North Sea workers, communities and supply chains.

In addition, the North Sea future plan also announces that the government will establish the “North Sea jobs service”, a national employment programme offering support for oil and gas workers seeking new opportunities in clean energy, defence and advanced manufacturing.

Nuclear, ‘green finance’, critical minerals and rail

The section in the budget about “investing in the UK’s energy security” largely focuses on the government’s plans for nuclear power.

At the last spending review, the government announced £14.2bn of investment in the planned Sizewell C nuclear-power plant in Suffolk.

The plant is set to be supported under the “regulated asset base” (RAB) model, which levies an extra charge on consumer energy bills to support the cost of the development. OBR analysis concludes this will generate £0.7bn in receipts in 2026-27, doubling to £1.4bn in 2030-31.

The budget also says the prime minister is issuing a “strategic steer” on the “safe and efficient delivery” of nuclear developments through “proportionate regulation and stronger collaboration”.

It says the government will additionally issue an “implementation plan”, within three months, in response to the recently published report on nuclear regulation. It says it will “complete implementation within two years”.

The government has also updated its “green financing framework”, which sets guidelines for the type of expenditures that can raise funding from investors under the UK’s green financing programme. It has now added nuclear power to the list of eligible expenditures.

Other climate-related measures mentioned in the budget include regional funding, such as £14.5m for a new low-carbon industrial centre in Grangemouth, Scotland, and support for “critical minerals, renewable energy and marine innovation” in Cornwall.

This builds on the government’s “critical mineral strategy” released last week, which specifically highlights Cornwall as a site of “mineral wealth”, where mining for lithium, tin and tungsten is being undertaken.

The government has also announced a one-year freeze on rail fares, which it states could save commuters taking expensive routes “more than £300 per year”.