COP30: Key outcomes for food, forests, land and nature at the UN climate talks in Belém

Multiple Authors

11.26.25The COP30 climate summit – held in the city of Belém, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest – saw the Brazilian presidency launch a new forest fund and promise a “roadmap” to put an end to deforestation.

Almost every country in the world signed off on a final COP30 package called the “global mutirão” – meaning “collective efforts” – after two weeks of talks ran into overtime amid deepening divisions, compromises and even a fire in the conference venue.

Countries also agreed on a set of indicators for countries to track their efforts on climate adaptation, including within the food and agriculture sectors.

Brazil’s much-anticipated tropical forest fund, launched just before COP30 officially began, raised $6.6bn, more than half of which will come from Norway and Germany.

In the second week of the negotiations, dozens of countries backed plans to agree on roadmaps to guide the move away from fossil fuels and deforestation.

Although these roadmaps did not make it into the final negotiated text, COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago said they will be developed outside the formal UN process.

The final mutirão text mentioned biodiversity loss, land rights and deforestation, but did not feature food – which disappointed some observers, including one expert who said food systems had been “erased” from COP30.

Meanwhile, the formal agriculture negotiations ended without a substantive outcome and talks are expected to continue next year.

Indigenous peoples featured strongly at COP30 and attended the summit in larger numbers than ever before. During the talks, $1.8bn was pledged for land rights and Brazil announced new Indigenous territories.

Below, Carbon Brief breaks down the main COP30 outcomes on food, forests, land and nature.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of key outcomes for food, forests, land and nature from COP29, COP28, COP27 and COP26.)

‘Global mutirão’

COP30 saw countries agree to a new “global mutirão” decision, a text calling for a tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 (later than some hoped), a new “Belem mission” to increase collective actions to cut emissions and – to the disappoint of many countries – no new “roadmaps” on transitioning away from fossil fuels and reversing deforestation. (See Carbon Brief’s snap analysis.)

“Mutirão” is a Portuguese word originating in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language that refers to people working together towards a common aim with a community spirit – something the COP30 presidency was keen to emphasise.

The presidency was also keen to stress that the mutirão text was not a cover text (sometimes referred to as a “cover decision”). However, like a cover text, it sought to bring together important issues that were not on the formal agenda with negotiated targets, acting as the key agreement from COP30.

The first draft of the mutirão put forward by the Brazilian presidency on 18 November included optional text to create a “high-level ministerial round table”, aimed at supporting countries to develop their own national roadmaps on transitioning away from fossil fuels and halting and reversing deforestation. (See: Deforestation roadmap.)

The language around this was criticised as weak by some observers, but its inclusion was widely welcomed.

The final mutirão decision did not mention fossil fuel or deforestation roadmaps. It did mention deforestation once, “emphasising” the importance of boosting efforts to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030 to help achieve the Paris temperature goal.

It noted that this is “in accordance with Article 5 of the Paris Agreement”, which is a section of the landmark climate deal that calls for strengthening of the world’s carbon sinks, including forests. (Carbon Brief understands that a large group of rainforest nations, called the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, were particularly keen to have Article 5 referenced in the final mutirão decision.)

The final mutirão decision makes multiple brief mentions of nature and the need to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss in a synergistic way.

Paragraph two of the agreement, in the section sometimes called the “preamble”, “emphasises” the importance of “conserving, protecting and restoring nature and ecosystem”.

Further down, in a section “recalling” the first global stocktake of climate action conducted at COP28 in Dubai in 2023, the text “underlines” the “urgent need to address, in a comprehensive and synergetic manner, the interlinked global crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and land and ocean degradation in the broader context of achieving sustainable development”.

This inclusion likely reflects the presidency’s keenness to prioritise “synergies” between climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation. (See: Climate and nature ‘synergies’.)

While the mutirão text included references to safeguarding Indigenous rights, conserving biodiversity and maintaining nature-based stores of carbon, no mention of food or agriculture appeared in any draft of the text.

Prof Raj Patel, a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), said in a statement that it was as if food systems were “erased” from the negotiations, adding:

“Two years ago, 160 countries signed a Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture with great ceremony. Today, they cannot bring themselves to mention the word ‘food’ in the mutirão decision.”

Adaptation

One of the major negotiated outcomes of the Belém summit was the agreement of a set of indicators for countries to measure their progress towards the global goal on adaptation (GGA).

The GGA, agreed at COP28 in Dubai, sets out 10 targets for countries to measure their progress towards, including targets on water scarcity, climate-resilient food systems and reducing climate impacts on ecosystems.

The initial list of indicators for these targets numbered 10,000. These had been whittled down by experts since COP28 and, at COP30, negotiators were tasked with agreeing on just 100 for countries to use.

Divisions were apparent from the first day of COP30, with the African group and Arab group proposing a two-year period for refining the GGA indicators before formally adopting them in 2027, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. This move was opposed by several other blocs, including the Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) and the EU.

Disagreements arose between countries on the need for finance in order to implement the GGA, whether indicators infringed on countries’ sovereignty and indicators around domestic financing.

Richard Muyungi, African group chair, told Carbon Brief in the first week:

“We need to put guardrails or caveats on the adoption [of the indicators]. For example…the indicators should not infringe on the sovereignty of countries, asking countries to change their laws, their strategies. I mean, you cannot ask my country to change laws, because they want to address the global goal.”

Ultimately, countries adopted a set of 59 indicators and agreed to a two-year work programme “aimed at developing guidance for operationalising the Belém adaptation indicators”.

The set included five indicators on assessing progress towards climate-resilient and sustainable food systems.

The indicators on ecosystems and biodiversity included measuring the proportion of ecosystems “providing services to populations that depend on them”, the level of adaptive capacity due to the implementation of nature-based solutions and the levels of threat status of ecosystems and species.

However, observers noted that the indicators were heavily caveated, with the introductory text of the agreement “emphasis[ing]” their voluntary nature.

(For more on adaptation and the GGA, see Carbon Brief’s explainer of COP30’s key outcomes.)

Tropical Forest Forever Facility and other forest pledges

At the COP30 leaders’ summit, Brazil officially launched the Tropical Forest Forever Fund to “reward” countries that conserve their tropical forests.

During the negotiations, the facility raised $6.6bn and had the support of 53 countries, including countries with tropical forests and those that will act as investors.

This instrument is intended to be a financial vehicle to raise $125bn from countries, philanthropy and private investors, which will then be invested in the global bond market. It is intended to be able to support up to 74 countries that have tropical forests across many regions, such as the Amazon and the Congo Basin.

The TFFF has been described as “the largest forest-finance mechanism ever created” and praised by Brazil’s finance minister, Fernando Haddad, as “innovative” for combining public and private financing.

However, it has also received criticism.

As Carbon Brief has previously reported, experts have concerns around fragmenting existing climate finance and inadequate accountability. Other criticisms have focused on worries that the fund could benefit investors over forest countries and that 20% of the funds being directed to Indigenous peoples is insufficient.

For Sandra Guzmán, founder and general director of the Climate Finance Group for Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC), the Brazilian government focused on moving forward with the TFFF and neglected other aspects of financing, such as the Baku to Belém roadmap to mobilise $1.3tn per year in climate finance by 2035. She told Carbon Brief:

“The TFFF is not a mechanism that has been agreed upon multilaterally. [If the fund fails in its mission], it would only confirm that Brazil could have [capitalised] on other funds that are within the [UN climate] convention and do have a future.”

After the launch of the TFFF, it was rejected by 150 civil society groups and Indigenous peoples’ organisations, who said the fund “does not seek to address the true structural causes of forest destruction” and “does not prioritise Indigenous peoples and local communities”.

The COP30 presidency stated that, in the second week of negotiations, governments, multilateral funds and Indigenous leaders met to discuss how an Indigenous governance model – known as Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM) – can “inform and strengthen the emerging generation of climate finance facilities”.

Analysis by the civil society organisation Leave it in the Ground (LINGO), presented at COP30, suggested that not extracting fossil fuels beneath forests eligible for the TFFF would prevent 4.6tn tonnes of CO2 from being released.

These emissions would be saved if countries “were to adopt a pledge of no fossil-fuel extraction in its forests”, the report said.

Kjell Kǘhne, director of LINGO, said in a press conference attended by Carbon Brief that while restrictions on fossil fuels are not part of the scope of the discussions of the TFFF, this would make it “even stronger”.

Other forest funds

Elsewhere at COP30, countries renewed their COP26 commitment to help protect rainforests in the Congo Basin, which contains the world’s second-largest area of tropical forest.

A Belém “call to action” pledged to raise more than $2.5bn for the cause over the next five years. This was put forward by Gabon and France and signed by Germany, Belgium, Norway and the UK, alongside development banks and other groups.

A new pledge of $1.8bn was put forward from more than 35 governments and philanthropic organisations to help secure land rights across forests and other ecosystems for Indigenous peoples, local communities and Afro-descendent communities, according to the Forest & Climate Leaders’ Partnership. (See: Indigenous representation.)

The UK also announced almost £17m in funding for the Accelerating Innovative Monitoring for Forests (AIM4Forests) programme, a cooperation between the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the UK that supports countries in monitoring and reporting on forests.

Meanwhile, Brazilian development bank BNDES approved R$250m (£35m) for ecological restoration and tree-management projects in parts of the Amazon and Atlantic forests, Brazilian outlet InfoMoney reported, adding that the funding will help to recover up to 19,000 hectares of forest land.

On 17 November, when forests featured as one of the COP30 themes of the day, more than 70 civil-society groups called on governments to set up forest “fossil-free zones” – areas where oil, coal and gas are not extracted – to protect forests and the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Earlier that week, Colombia said it was the first Amazonian nation to keep its entire Amazon forest area “free from oil and mining activities”, InfoAmazonia reported.

Countries that hold the Amazon rainforest, including Brazil, Peru and Colombia, also launched an initiative, called Amazonia Forever, to gather more than $1bn to invest in Amazonian infrastructure and cities.

Brazil’s planning and budget minister, Simone Tebet, said this programme for cities and resilient infrastructure would “enable us to take action not only on forest and water resources, but also on urban challenges”.

Agriculture and food security

With agribusiness giant Brazil hosting this year’s summit, many expected COP30 to have a stronger focus on agriculture and food than previous years.

Formal negotiations for agriculture and food systems under the UN climate convention fall under the Sharm el-Sheikh joint work on the implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security (SJWA). COP30 ended without a substantive outcome for the SJWA.

The current four-year mandate of SJWA – which runs workshops, is developing an online portal and prepares an annual synthesis report of agriculture-relevant work undertaken by UN climate convention bodies – began in 2022 and runs out at COP31 next year.

At COP30, the main points of discussion for countries were a consideration of the outcomes of a workshop on “systemic and holistic approaches” to implementing climate action on food and agriculture, as well as countries weighing in on a special forum of the standing committee on finance (SCF) on financing for sustainable food systems and agriculture.

As the summit got underway in Belém, several parties began pushing the idea of capturing key messages from the workshop and forum into a formal SJWA decision.

Observers told Carbon Brief that Argentina, the African group and the least-developed countries (LDCs) wanted “means of implementation” – shorthand for finance – added to the text, while the EU opposed references to “Article 9.1” in the agriculture workstream. (See: Climate finance in Carbon Brief’s main COP30 outcomes piece.)

The next day, various blocs circulated text proposals on recognising the workshop outcome. These texts, seen by Carbon Brief, included proposals from the EU and the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) on food systems “which span the entire value chain”, links to biodiversity, “precision agriculture” and market-based rewards for farmers.

G77 and China, meanwhile, flagged 13 points for inclusion in the draft text, including recognising the “fundamental priority of ending hunger” and a call for developed countries to “significantly scale up…grant-based finance for adaptation actions in agriculture”.

Language from all of these proposals was incorporated into a draft text released on the first Thursday of COP30.

This draft – with 23 square brackets, indicating text not yet agreed – included many references, ranging from agroecology to AI-farming and using “high-integrity carbon-market approaches under Article 6” to reward farmers.

It also recognised that the World Trade Organization (WTO) “can be useful in ensuring a stable, predictable global agricultural trade underpinned by rules” that support climate action.

Five hours later, this was replaced by a brief draft, which postponed further discussions until June next year, taking into account the earlier text.

Many observers expressed their dismay at negotiations finishing so abruptly, before the end of week one and without a substantive outcome.

Teresa Anderson, global climate justice lead at Action Aid International, told Carbon Brief that negotiations “took a turn for the worse” after Australia and the EIG “pushed for dodgy language” on what could be considered “systemic” and “holistic”. Anderson said:

“In June, many countries talked about agroecology. And yet here in the COP, Australia and others just submitted language on precision agriculture, on AI and just basically a lot of corporate greenwash…Countries weren’t able to agree on [this] because there was just too much new nonsense in there.”

The final draft conclusions “recognised that progress was made at these sessions” and “noted that more time is needed to conclude the discussions thereon”.

Article 6

Carbon markets – particularly relating to forests – were expected to be a key priority for the Brazilian presidency at COP30.

On 7 November, the Brazilian presidency launched a global coalition on “compliance carbon markets”, endorsed by 18 countries.

The voluntary initiative said it is designed to allow members to “share experiences and learn from each other”. It also said the coalition will “explore options to promote interoperability of compliance carbon markets in the long term”.

Finally, it mentioned information exchange on the “potential use of high-integrity offsets”, referencing a sector that has faced intense scrutiny in recent years.

The same day, Honduras and Suriname announced a deal to issue “high-integrity rainforest carbon credits” in partnership with Deutsche Bank, German agrochemical giant Bayer and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations (CfRN).

Formal negotiations on carbon trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement were expected to be somewhat muted, but ended up being rather complicated.

In Baku last year, countries had finally agreed on the rules for country-to-country carbon trading under Article 6.2 and for a new international Paris Agreement carbon market under Article 6.4, bringing a decade of negotiations to a close. Countries also agreed to undertake a review of these rules in 2028.

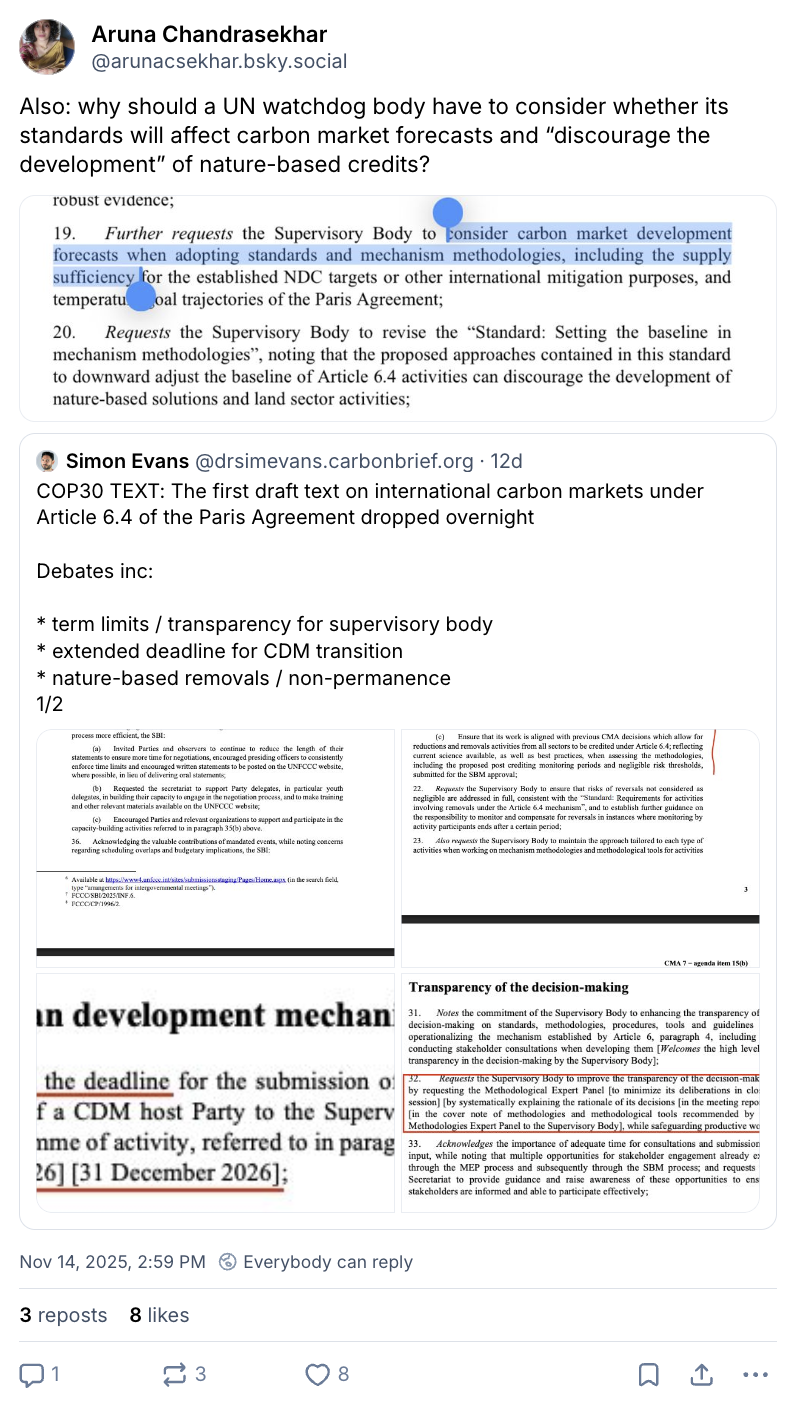

Within the Article 6.4 market, key tools for “nature-based” removals and rights safeguards were still being developed after COP29 by the “supervisory body” in charge of standards.

At COP30, negotiations focused on the annual report of this body, which had been given autonomy to set these standards at COP29.

The supervisory body had recently adopted a standard on non-permanence on 10 October, which had been the subject of heated debate in the sector.

The standard describes how to handle the risk of someone selling carbon credits for a project that removes CO2 from the atmosphere, only for this stored carbon to be released back into the atmosphere. This is a phenomenon known as “reversal” and is particularly pertinent for tree-planting projects, which may be at risk from wildfires and drought.

In a joint letter published on 12 November, a group of NGOs and carbon-trading advocates said this and other standards “could exclude all land-based activities”, such as forests, from the Article 6.4 market.

They called for new guidance to be given to the supervisory body to prevent this from happening. Their recommendations on amending the rules around reversal risk to give more scope to include nature-based projects – which were opposed by some scientists and other NGOs – were picked up and reflected in an early draft text at COP30.

This text, published on 14 November, asked the market’s supervisory body to “consider carbon market forecasts” and revise its standards so as not to “discourage the development” of nature-based solutions.

At the same time, text options “urging” the body to make its decisions more transparent and “minimise time in closed-door sessions” were heavily bracketed.

In response to this draft text, Isa Mulder of Carbon Market Watch told Carbon Brief:

“All of the pro-market flexibility in there [would] completely undermin[e] the Paris Agreement.”

On 15 November, Climate Action Network awarded Indonesia its “Fossil of the Day” for repeating “lobbyists’ talking points” surrounding weaker rules on the permanence of nature-based credits – “sometimes verbatim” – in its intervention in Article 6.4 negotiations.

While explicit references to nature and nature-based carbon crediting projects were removed in a second draft issued late on 15 November, the text still asked the body to apply a “tailored approach” and weigh the “economic feasibility” of its standards.

In the end, references to these two terms were also dropped. Many countries saw the effort to give detailed guidance to the supervisory body as an attempt to “micro-manage” its work, creating uncertainty for market actors.

The final decision on Article 6.4 gave carbon-credit projects registered under the “clean development mechanism” (CDM) a six-month deadline extension, until June 2026, to “transition” into the Paris Agreement’s new carbon market.

In theory, this could allow up to another 760m tonnes of CO2-equivalent of credits to enter the Paris Agreement regime.

The final Article 6.4 decision “averted disaster” and could potentially make the UN-backed carbon market “marginally” more inclusive, according to Carbon Market Watch, which added that these improvements “do little to change the rather worrying course that Article 6 seems to be on”.

The decision “reiterates” that supervisory body members should not have “any financial or other interests” that could affect – or be seen to affect – their impartiality.

It also “requests” that the body strengthen its consultation processes by informing, reaching out to and including Indigenous peoples, local communities and others who “cannot easily participate” in the complex mechanism.

While there are fewer rules that govern country-to-country carbon trading under Article 6.2, countries were supposed to submit “initial reports” of these bilateral carbon-trading deals for review by technical experts ahead of COP30.

The first six reviews – including a Swiss-supported project to promote “climate-smart” rice cultivation in Ghana and sustainable forest management in Guyana and Suriname – were completed ahead of the summit.

A particular issue being considered at COP30 was the fact that, to date, “all trades” under Article 6.2 so far have been flagged with “inconsistencies” during expert review.

The COP30 Article 6.2 decision simply “notes” these inconsistencies and “urges” countries to sort them out, while adding that the reporting and review process is still “in the early stages”. It also asks reviewers to “clearly explain” any issues they find and how to resolve them.

Deforestation roadmap

During the Belém talks, momentum began to build around agreeing a roadmap to end deforestation, although it was largely overshadowed by the push for a similar fossil-fuel phase-out plan.

At COP26, more than 130 countries had signed on to a non-binding pledge to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. This pledge was formally recognised in the global stocktake agreed at COP28. Although the rate of deforestation is decreasing, countries are off track to meet this goal.

A roadmap aimed to help achieve this deforestation target did not appear in the final mutirão decision agreed at COP30. However, in the closing plenary of the summit, Corrêa do Lago said the Brazilian presidency would work to create deforestation and fossil-fuel roadmaps outside the COP negotiation process.

In a speech at the opening of the leaders’ summit before COP30 began, Lula had called for roadmaps to “reverse deforestation, overcome dependence on fossil fuels and mobilise the resources required to achieve these goals in a fair and planned manner”.

By the second week of negotiations, around 45 countries backed a deforestation roadmap, including Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, the EU and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to a Carbon Brief tracker. This increased to at least 92 countries by Friday 21 November, after a large group of more than 50 rainforest nations got behind the proposal.

WWF and Greenpeace had urged countries to adopt the deforestation roadmap “as a formal outcome at COP30”, while Colombia’s environment minister, Irene Vélez-Torres, wrote in Backchannel, a climate commentary platform:

“We need to see the global north come behind a roadmap – and quickly.”

However, the final text signed off on 22 November did not include mentions of either roadmap. (See: ‘Global mutirão’.)

Although more than 90 countries backed the deforestation roadmap, “wider political will to secure this in Belém was lacking”, WWF said in a statement.

Carolina Pasquali, executive director of Greenpeace Brazil, said that Lula’s government had “set the bar high” in calling for deforestation and fossil-fuel roadmaps, but the “divided multilateral landscape was unable to hurdle it”.

After the talks ended, Prof Nathalie Seddon, the director of the nature-based solutions initiative at the University of Oxford, said in a statement:

“Until we have coupled roadmaps for ending deforestation and phasing out fossil fuels, grounded in rights and direct finance for those who safeguard ecosystems, we will remain off track for a safe and just future.”

‘Unilateral trade measures’

After several failed attempts to bring climate-related “unilateral trade measures”, such as the EU’s deforestation regulation, onto the agenda at previous COPs, the issue was taken up in Belém as part of presidency-led discussions and reflected in the key outcome of the summit, the “global mutirão”.

This decision creates three annual “dialogues” on trade, to be held at the Bonn intersessional meetings in 2026, 2027 and 2028. It also “reaffirms” that climate measures, “including unilateral ones, should not constitute” trade restrictions that are “arbitrary” or “discriminat[ory]”.

This is the first-ever mention of trade measures in a COP cover decision.

While the issue of trade has received a significant level of attention at recent summits, it is not a new one for the UN climate regime. The text agreed in Belém, below, precisely repeats the language in article 3.5 of the 1992 UN climate convention.

In Belém, the issue of such measures had once again been raised by Bolivia on behalf of the like-minded developing countries (LMDCs, a group that includes China, India and others).

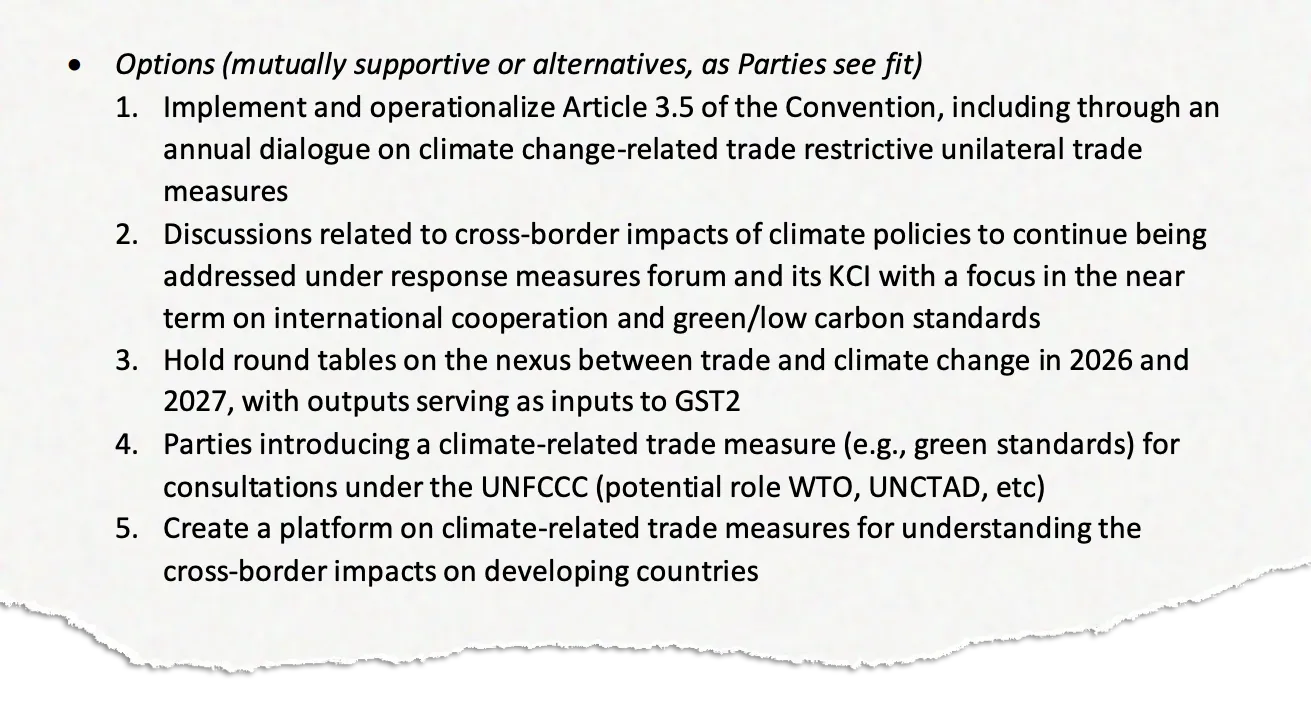

Within the presidency-led consultations, the LMDCs called for a recurring agenda item on trade, Tuvalu supported a dialogue and the African group proposed a system for countries to report new trade measures to the UN climate convention, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

On Sunday in the middle of COP, the presidency published a summary of its consultations, containing five options for a decision on trade measures, including dialogues, roundtables or the creation of a platform.

David Waskow, director of the international climate initiative at the World Resources Institute thinktank, told a media briefing that trade is a “real issue” for some countries and not just a “bargaining tactic or some sort of chit that’s being put on the table”.

He added that the EU “feels strongly” about the ways trade measures support climate action, but developing countries have “real concerns” about how those measures play out.

Avantika Goswami, climate-policy lead at Delhi-based thinktank the the Centre for Science and Environment, told Carbon Brief that, while it is “not ideal to not have a formal agenda item” on unilateral trade measures, the reference to the UN climate convention in the text “is welcomed”, as well as the dialogues that will take place over the next three years. Goswami added:

“At the very least, this will elevate the issue of unilateral trade measures to be more high-profile within the COP space and will provide a forum for countries to discuss their concerns and challenges, as well as possible solutions for the way forward.”

Alongside the discussions under the presidency, these measures continued to crop up within different negotiation streams, including on just transition, “response measures” and technology.

The final decision on the just transition work programme removed all references to trade, although it recognised the role of smallholder farmers and food production.

Anderson, from ActionAid, told Carbon Brief that civil society had “fought hard” to make sure food and farmers were included in the just transition discussion. She told Carbon Brief:

“We’ve been calling for a just transition in agriculture because agriculture is the [second biggest] polluter after fossil fuels, and the [biggest] employer in the world.

“We know we need to transition in agriculture, but it has to be fair to protect jobs, livelihoods, families, communities and global food security. That is really, really important, because we know there’s a lot to learn from many years of climate action that hasn’t always put rural communities, who are often marginalised, first in the conversation.”

Biofuels

On 14 October, at the pre-COP in Brasilia, the Brazilian presidency launched the Belém 4x pledge, which aimed to gather high-level support to quadruple the production and use of “sustainable fuels” – such as hydrogen and biofuels – by 2035, as compared to 2024 levels.

The pledge was co-sponsored by Italy and Japan, supported by India and has been backed by 23 countries so far, including Canada and the Netherlands. On 14 November, Brazil announced a partnership with the Clean Energy Ministerial to “advance Belem 4x”.

However, the pledge was “rejected” by some NGOs, including Climate Action Network and Greenpeace, who criticised the environmental, social and food security impacts of biofuels.

Hikmat Soeriatanuwijay at Oil Change International said in a statement:

“The Belém 4x pledge uses the language of sustainability to justify continued fossil-fuel use. The [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] states that forest protection will have the highest mitigation value; however, exploitation of natural forests and cropland for bioenergy undermines this priority.”

The 4x pledge was based on the International Energy Agency’s report on “delivering” sustainable fuels, which included “woody biomass” being converted into biofuels.

However, the IEA report also warned that, for fuels to be considered sustainable, they “need to comply” with other criteria, “such as preservation of biodiversity, sustainable water management and compliance with social safeguards”.

In a statement from the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA), former Tasmanian Greens leader Peg Putt from the Biomass Action Network called the pledge’s promotion of liquid and gaseous fuels derived from wood a “dangerous distraction”. Putt said:

“The combustion of wood for bioenergy releases massive amounts of stored greenhouse gases immediately and the myth of its carbon neutrality is based on flawed accounting that ignores the decades forests need to regrow, if they ever do. The true carbon cost rarely appears on any national balance sheet.”

Many observers feared that biofuels would be included in the negotiations or in COP30’s cover decision.

As of an 18 November informal note, elements for a decision on the just transition work programme still referred to the role of “transitional fuels”.

That term has no officially agreed definition, although many states believe that it covers bioenergy and biofuels.

This option was deleted from draft text published on 21 November, and is not reflected in the final just transition work programme decision.

The final global mutirão decision also had no explicit mention of biofuels, transitional fuels or sustainable fuels.

Food systems and water

Transforming food systems and agriculture was one of the six “pillars” on the COP30 “action agenda”, but many observers were disappointed with the outcomes on food in Belém.

Food solutions were “on display” at COP30 – in the form of local dishes served to delegates and new pledges announced – but “none of this made it into the negotiating rooms or the final agreement”, said Dr Elisabette Recine, a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food). She added in a statement:

“Despite all the talk, negotiators failed to act, and the lived realities of those most affected by hunger, poverty and climate shocks went unheard.”

Outside the formal negotiations, a number of new pledges were announced, including the Belém declaration on hunger, poverty and human-centered climate action, which aims to address the “unequal distribution of climate impacts”.

This was adopted by 43 countries and the EU and focused on a number of actions, including supporting climate adaptation for small farmers and expanding social-protection systems, such as government unemployment and illness pay. The German cooperation and development minister described it as a “pioneering step in linking climate action, social protection and food security”.

The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) launched a food waste initiative to help halve food waste by 2030 and also target a reduction in methane emissions of up to 7%, as food waste is a source of the potent greenhouse gas. (See: Methane.)

The food waste pledge was backed by Brazil, Japan and the UK, alongside several cities and private companies, and included goals for governments to integrate food waste into climate and biodiversity plans.

The thematic days for food and agriculture on 19 and 20 November saw a raft of other new announcements, including Brazil launching the resilient agriculture investment for net-zero land degradation (RAIZ).

This initiative is aimed at bringing together governments and investors to restore degraded farmland. It was backed by 10 countries, including the UK, Australia and Saudi Arabia.

An FAO press release said RAIZ will help governments to attract more funding and allocate investment towards restoring agricultural land. No specific financial goal was mentioned, but Bruno Brasil from Brazil’s ministry of agriculture said in a statement that it could “unlock billions globally to restore degraded farmland, protect biodiversity and ensure food security”.

Brazil and the UK also put forward a declaration to spur action around reducing the environmental impact of fertilisers. This expressed “intent” to prioritise sustainable production of fertilisers and improved nutrient management, alongside recognising that improper use of fertilisers “threaten[s] our ecosystems and food systems”.

Additionally, some initiatives launched at previous COPs were updated in Belém. Colombia, Italy and Vietnam joined the Alliance of Champions for Food Systems Transformation – a coalition of countries pledging to take strong action on transforming food systems that was first launched at COP28.

A number of reports released during the talks looked at how food systems were included in countries’ climate plans, called “nationally determined contributions”, or NDCs. A report from WWF and Climate Focus found that 93% of new NDCs included at least one measure around agriculture or food systems, an increase from 86% of previous pledges.

Another NGO assessment of how food systems were incorporated into 10 NDCs found that pledges from Somalia and Switzerland were “very strong” in this regard and included actions from across the entire food system. Climate pledges from Brazil and New Zealand, on the other hand, were ranked as “weak”, the report said.

Sebastian Osborn from Mercy for Animals, one of the organisations involved in the assessment, told a press conference:

“Overall, countries are not fully embracing the potential benefits of incorporating food systems into their climate policies.”

Elsewhere, the Gates Foundation put forward $1.4bn for smallerholder farmer climate adaptation in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia. The Rockefeller Foundation announced more than $5.4m to “strengthen the resilience” of food systems and provide children’s school meals.

In terms of water and ocean outcomes, six more countries joined the “blue NDC challenge”, an initiative launched by Brazil and France earlier this year that encourages nations to integrate ocean measures into their climate pledges.

Finally, analysis from the World Resources Institute, Ocean & Climate Platform and Ocean Conservancy found that more than 90% of new NDCs submitted by coastal and island countries included ocean-based climate actions, an increase from 73% in 2022.

Climate and nature ‘synergies’

Some hoped that a first-of-its-kind outcome on jointly addressing climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation could emerge from COP30.

However, in the end, pushback from some nations scuppered plans for a new “synergies” agreement.

At the Rio Earth summit in 1992, the world decided to address Earth’s most pressing environmental problems under three separate conventions: one on climate change, one on biodiversity and the final one on land desertification.

But, for the past few years, a growing number of scientists, politicians and diplomats have questioned whether tackling these issues separately is the right approach.

And, at the most recent biodiversity and land desertification COPs, countries agreed to new texts calling for closer cooperation between the three Rio conventions.

Speaking at a side event on nature at COP30, Juan Carlos Monterrey, Panama’s hat-sporting special climate envoy, said that countries committed a “big sin” when they decided to “decided to split the environment into three different structures”.

(Panama has plans to be the first country to publish one document that will function as both its climate plan – known as a “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) – and its nature plan – known as a “national biodiversity strategy and action plan” (NBSAP).)

After pledging to make COP30 a “nature COP”, the presidency held consultations on an agenda item called “cooperation with other international organisations”, with the hopes of producing the first substantive outcome on addressing climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation together.

A draft “areas of interest” text linked to the issue spoke of “creat[ing] a space for continuous discussions to enhance cooperation among the Rio conventions” and the “establishment of a process to come up with a set of recommendations on how to enhance cooperation and policy coherence”.

However, several nations, including Saudi Arabia, vocally opposed the progression of a substantive outcome – and the final version of the “synergies” text is just five paragraphs long, containing little that is new.

Observers pointed out to Carbon Brief that Saudi Arabia’s opposition was particularly puzzling, given it currently holds the presidency for the desertification COP.

In an interview with Carbon Brief, Dr Osama Faqeeha, deputy environment minister for Saudi Arabia and chief adviser to the COP16 desertification presidency, said that the nation did not support any action that might lead to “dissolving the conventions”.

When pressed on whether, as the COP16 desertification presidency, it should be prioritising more “synergistic” work between the three Rio conventions, Faqeeha added:

“We have to realise the convention is about land. Preventing land degradation and combating drought. These are the two major challenges.”

Bethan Laughlin, a senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, said the final synergies text “fell short of the high ambition championed by many countries and civil society”, but does offer some hope for future collaboration. She told Carbon Brief:

“This agenda item may not have had a substantive outcome in the text, but it also did not fail. Countries have committed to continued dialogue and collaboration, moving [the agenda item] beyond its previous relegation as a brief annual intersessional discussion – towards meaningful political engagement.”

Indigenous representation

COP30 achieved several milestones for Indigenous peoples, including securing recognition of their land rights in the mutirão decision and agreeing on a just transition mechanism that ensures that Indigenous peoples rights are included.

Belém’s climate summit was attended by more than 3,000 representatives of Indigenous peoples, making it the largest participation of Indigenous peoples in the history of COPs.

However, Cultural Survival – a not-for-profit organisation that supports Indigenous rights worldwide – said in a statement that this COP was “one of the most frustrating and disappointing” for Indigenous peoples. It noted that only 14% of 2,500 Indigenous representatives from Brazil received accreditation to access the official negotiations area.

Fany Kuiru, general coordinator of the Coordinator of Indigenous Organisations of the Amazon Basin (COICA), told Carbon Brief that some Indigenous representatives felt discontent due to a lack of “full and effective” participation.

On the second day of COP30, dozens of Indigenous protesters clashed with security guards in order to enter the negotiations and demand climate action and forest protection.

Emil Gualinga, a member of the Kichwa Peoples of Sarayaku, in Ecuador, said in a press release that Indigenous peoples continue to be excluded from negotiation rooms and most of their proposals were not incorporated into final decisions.

In Belém, Brazil’s minister of Indigenous peoples, Sonia Guajajara called for the mutirão text to integrate the demarcation of Indigenous lands as a climate policy.

Indigenous peoples viewed this statement as “quite positive”, Toya Manchineri, general coordinator of the Coordination of Indigenous Organisations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB), said at a press conference attended by Carbon Brief.

Currently, few countries’ climate plans recognise the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples as climate instruments, according to a recent report that analysed the NDCs of 15 countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

One of the major outcomes of COP30 for Indigenous peoples was the commitment to allocate $1.8bn to support Indigenous peoples and Afrodescendants’ tenure rights from 2026 to 2030 as part of the Forest and Land Tenure Pledge. Another finance-related outcome was the establishment of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility, which guarantees that 20% of its funds will go to Indigenous groups. (See: Tropical Forest Forever Facility and other forest pledges.)

Additionally, 15 countries committed to a collective target to recognise and secure land tenure of 160m hectares by 2030 for Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant communities. Brazil announced the demarcation of 10 new Indigenous territories and acknowledged that 59m hectares must be secured over the next five years.

The preamble of the mutirão decision also recognised Indigenous rights, including their land rights and traditional knowledge.

Gualinga, the Ecuadorean Indigenous leader, said in a press release that this recognition was an “important step forward and it gives us tools to continue advocating for our rights in future decisions”.

However, he noted that Indigenous groups had proposed more robust language in the mutirão text, such as including their full and effective participation in the development and implementation of NDCs, as well as direct access to financing.

Indigenous peoples also demanded that the climate finance received by countries must include their traditional knowledge and “explicit guarantees” of principles such as free, prior and informed consent, legal security of land, Indigenous land tenure and complaint mechanisms, Kuiru told Carbon Brief.

She added that Indigenous communities have their own mechanisms for managing funds and that “have already demonstrated to be efficient”, which is why they advocate for direct funding to Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples around the world have struggled to receive such funding directly. Only 0.7% of climate finance provided to developing countries mentions the word “Indigenous”, a new study by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) found.

The mutirão decision ultimately did not include direct access to climate finance for Indigenous peoples.

Methane

Methane – the potent greenhouse gas that is the second-biggest contributor to global warming, after CO2 – featured in several COP30 pledges and announcements, but overall did not make major waves in Belém.

A UNEP report released during the summit looked at countries’ progress towards meeting the voluntary global pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030, which has been backed by almost 160 countries since its launch at COP26.

The report found that while progress has been made on the extent of the increase in methane, emissions are still rising each year. Based on current government pledges, methane emissions will reduce by 8% by 2030, but they could reduce by 32% with more ambition and “full implementation of existing technically feasible reductions”, the report found.

Martin Krause, the director of the climate-change division at UNEP, said at the report’s launch that drastically cutting methane is “like pulling the climate emergency brake”, saying countries should “pull that brake hard and fast”.

Caitlin Smith at the Changing Markets Foundation campaign group said in a statement that to make progress on cutting methane, governments must “ramp up action on agriculture – the biggest source of methane, yet a blind spot for most rich countries”.

Research from thinktank Planet Tracker – released just before COP30 – found that 52 of the world’s largest meat, dairy and rice companies emit a combined 22m tonnes of methane every year.

The report also found that only seven of these 52 companies directly report the distribution and scale of their methane emissions and just one – Danone – has a specific methane-reduction target.

Also during the talks, the Changing Markets Foundation launched an interactive tool tracking agricultural methane emissions from companies and countries around the world.

Meanwhile, Farmers Weekly reported that the UK government “quietly shelved” plans to announce a national pledge to cut livestock methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

The UK, Brazil and China hosted a methane summit on the weekend before talks officially began. During this event, the Climate and Clean Air Coalition launched an “action accelerator” to help governments in developing countries cut emissions from super pollutants, including methane.

Brazil, Cambodia, Nigeria and four other countries have been initially chosen for this initiative and will receive a combined $25m to “advance their efforts in this area. The plan aims to work with up to 30 countries by 2030 and gather around $150m in funds. Additionally, 11 countries signed a statement committing to “drastically reducing” fossil methane emissions.

Other measures were announced in Belém, including a joint strategy to boost methane reductions across the agriculture, energy and waste sectors in developing countries, launched by the Global Methane Hub and the Global Green Growth Institute.

This initiative will focus on Mexico, Nigeria and Senegal, a statement said.

On 19 November, a scheme to boost efforts to cut methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture was launched. The farmers’ initiative for resilient and sustainable transformations (FIRST) aims to help countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia share “practical, low-cost solutions that cut emissions, strengthen food security and improve resilience”, a statement from the Climate and Clean Air Coalition said.

Some funding was also put forward for tackling methane, with businessman Mike Bloomberg announcing $100m in investment towards methane-cutting efforts, such as satellite monitoring of leaks of the gas.

Bloomberg told a press briefing attended by Carbon Brief that methane is an “extremely important part of the climate puzzle”.

Agricultural greenwashing

Brazil is a major producer of soya beans, beef, rice, biofuels and many other agricultural products. As a result, observers and media outlets were keenly watching out for any instances of agribusiness-related greenwashing or lobbying at COP30.

Before the negotiations began, DeSmog published a list of eight “big ag greenwashing terms” to watch out for in Belém. These included phrases such as regenerative agriculture, as well as arguments around fossil fuels and ways of measuring methane emissions.

The outlet published a number of other articles during the talks, reporting (alongside the Guardian) that more than 300 agricultural lobbyists attended COP30, mapping out the food and farming companies and trade groups at COP30 and detailing the social media influencers “enlisted” by agribusiness companies ahead of the talks.

“Sustainable” claims around biofuels also came under scrutiny in Belém. DeSmog identified nearly 60 events on the benefits of biofuels at COP30, led by both industry groups and related companies.

These included a “high-level event on the critical role of biofuels” and a “sustainable biofuels” section in the summit’s action agenda.

Unearthed reported that a COP30 sustainable agriculture pavilion, located around 2km outside the official “blue zone” where negotiations took place, was “sponsored by agribiz interests linked to deforestation and anti-conservation lobbying”.

Campaigners protested against “big agriculture lobbyists” outside this “AgriZone” pavilion during the negotiations, the Grocer said.

The Associated Press said the pavilion sought to “spread a message of lower-carbon agriculture possibilities”, but added that “industrial agriculture retains a big influence at the climate talks”.

Brazilian outlet Agência Pública, meanwhile, reported that Brazil placed the “billionaire brothers” who own JBS, the world’s largest beef producer, on a “VIP list” at COP30.

The Changing Markets Foundation also published a report looking at COP30 events led by the agriculture industry and assessing Brazil’s “agricultural methane blind spot”.

Teresa Anderson, global climate justice lead at Action Aid, told Carbon Brief that agribusiness was the “elephant in the room” at COP30. She added:

“We’ve had this COP set in the Amazon, with the Brazilian presidency, talking a big game on forests, but absolute crickets when it comes to naming the biggest threat to forests, which is big industrial agriculture.”