Rapid emissions cuts would avoid 64cm of ‘locked in’ sea level rise by 2300

Ayesha Tandon

10.24.25Ayesha Tandon

24.10.2025 | 11:44amCutting emissions in line with the 1.5C warming limit, rather than following current climate policies, could curb long-term sea level rise by 64cm, a new study says.

The research, published in Nature Climate Change, projects how much sea level rise will be unavoidable – or “locked in” – by the year 2300, due to emissions over the coming decades.

According to the authors, 29cm of global average sea level rise is already in the pipeline due to the emissions that were released up to the year 2020.

Following current climate policies until the year 2090 will “lock in” an additional 79cm of sea level rise for the year 2300, the study finds.

However, reducing emissions in line with 1.5C would cut this additional sea level rise to 15cm.

The analysis shows that “if we reduce emissions rapidly in the coming decades, there is a clear path to limiting the legacy of sea level rise”, the lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief.

The study also explores regional sea level rise, showing that Pacific small-island nations will face some of the highest rates of sea level rise.

A scientist not involved in the research tells Carbon Brief that the paper “exposes a deep inequity” between nations, arguing that this makes “ambitious” action to cut greenhouse gas emissions “not just a climate necessity, but a climate-justice imperative”.

‘Locked in’

Average global sea level has risen by more than 20cm since 1900, driven mainly by human-caused climate change through thermal expansion of the ocean and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

Rising seas are already threatening to wipe out small-island nations, jeopardising the security, livelihoods and cultures of people who live in these areas. Meanwhile, coastal regions around the world are facing more frequent flooding, erosion and saltwater intrusion.

The authors of the new study explain that emissions released over the coming decades will affect global sea levels for hundreds of years. This is because the oceans and ice sheets respond slowly to past and present warming, they note.

The authors call this “locked in” or “committed” sea level rise.

The study explains that sea level projections are generally based on 21st century emissions pathways, but notes that “late-century emissions then dominate the longer-term sea-level response and mask the impact of near-term emissions”.

In contrast, this study assesses the impact of emissions both early and late in the 21st century – including past emissions and those projected to occur under different emissions pathways. The research investigates how much sea level rise will be locked in by the year 2300 through these emissions.

According to the authors, 29cm of global average sea level rise, compared to 1995-2014, is already locked in due to the emissions that were released up to the year 2020.

Rising seas

The study uses emulators – simple climate models with lower time and computational costs than full-scale Earth system models – to model how much sea level rise will be locked in by 2300 due to 21st century emissions.

The authors chose five emissions pathways and ran multiple model runs where they simulated sudden stops in emissions at the end of each decade for each pathway. This allowed them to isolate the emissions just until these dates.

For example, modelling a sudden drop in emissions in the year 2050 allows the authors to calculate how much sea level rise over the next two centuries is driven solely by human-caused emissions released over the next two decades.

The authors use five emissions pathways:

- SSP1-1.9: A very-low emissions reductions pathway “consistent with” the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit

- SSP1-2.6: A “low” emissions pathway consistent with 2C of warming

- SSP2-4.5: A “current climate policy-like trajectory”

- SSP3-7.0: A “high” emissions pathway

- SSP5-8.5: A “very-high emissions” pathway

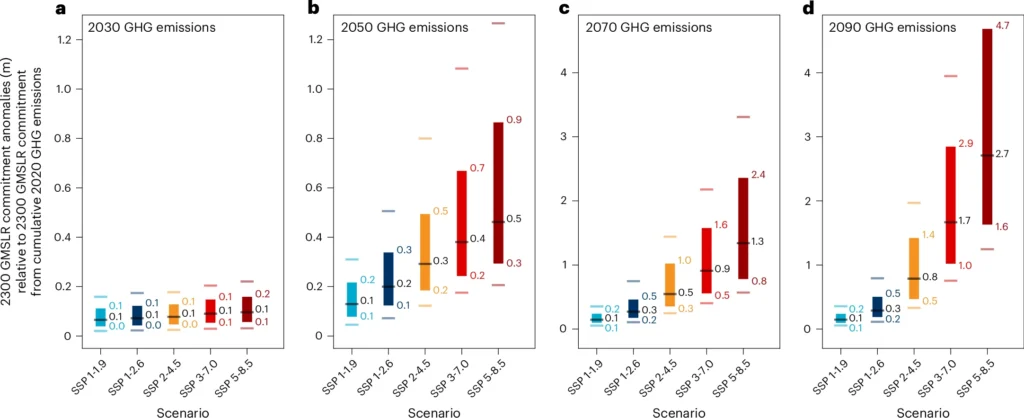

The left-most panel shows how much additional sea level rise is locked in for the year 2300 due to emissions produced between 2020 and 2030. The next three panels show the results for emissions produced between 2020 and 2050, 2070 and 2090, respectively.

The plot shows that higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions lock in more sea level rise for the year 2300.

The authors find that, under the SSP2-4.5 “current climate policies” scenario, human-produced greenhouse gas emissions over 2020-50 will lock in an additional 29cm of sea level rise by the year 2300. This number grows to 79cm when including emissions out to 2090 under this scenario.

Meanwhile, under the scenario consistent with the 1.5C limit, only 15cm of additional sea level rise will be locked in by 2090.

This means that efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions over the coming decades could curb long-term sea level rise by an extra 64cm.

The study authors say that their results “reinforce how every increment of additional peak warming from cumulative emissions irreversibly increases sea level rise”.

Dr Alexander Nauels is a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and lead author on the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the world is “already committed to a really substantive amount of sea level rise” and stresses that this must be considered in terms of “adaptation, planning and risk management”.

However, he adds, “if we reduce emissions rapidly in the coming decades, there is a clear path to limiting the legacy of sea level rise that we would produce in the coming decades”.

Dr Catia Domingues, is a researcher at the UK’s National Oceanography Centre and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that the study’s methodology is “clever and necessary”. She adds:

“[The study] clearly shows how the emissions from just the next 30 years, under current climate policies, will write an irreversible chapter for centuries to come, locking in significant sea level rise on their own.”

Warming levels

The authors also calculate the committed sea level rise at different warming levels.

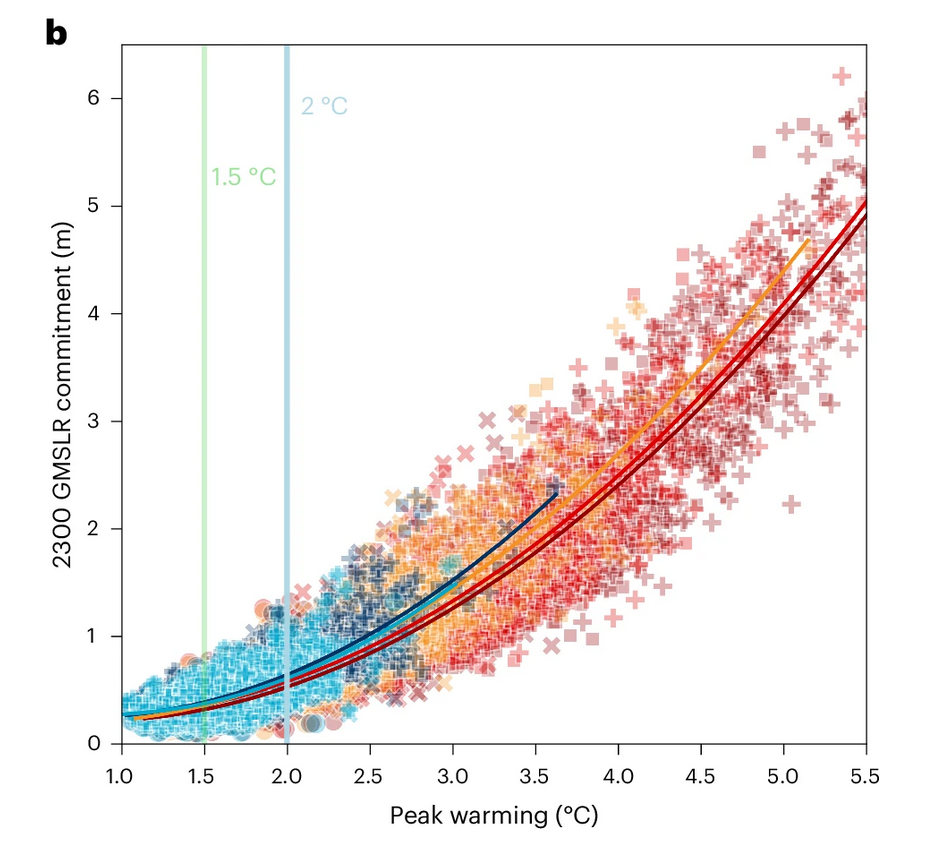

The chart below plots sea level rise against warming level for every scenario and time period used in the study. It highlights how higher levels of warming commit the world to ever higher seas.

The authors note that the relationship between global temperature and committed sea level rise to 2300 is not “linear”, noting that the amount of sea level rise that is locked in by warming accelerates as global temperatures rise.

The authors explain that this is due to a “non-linear increase in ice mass loss in a warmer world” – in other words, physical feedbacks mean that higher levels of warming could see disproportionately large increases in ice losses.

Nauels tells Carbon Brief many sea level processes, such as ice-sheet responses, are still not “fully understood”. This means that when looking out to 2300, there can be “large uncertainties” in results, he adds.

Nevertheless, he argues that it is “still very important to explore the longer-term sea level response, because of the huge risk that is attached to it”.

Inequity

The main findings of the study focus on global average sea level rise. However, the authors note that sea level rise is not consistent across the world, with some regions facing faster rates of sea level rise than others.

This is largely due to ocean currents, driven by wind, warming, evaporation and rainfall, which push large masses of water around the planet. It is also caused by the bumpy, non-uniform surface of the earth.

To show these differences, the authors also selected a handful of coastal regions to study.

Nauels tells Carbon Brief that the study authors decided to focus on a handful of regions that “diverge” from the average global trend.

For example, they find that Pago Pago – the capital of American Samoa, which is made up of a string of coastal villages – will experience greater committed sea level rise than the global average.

On the other hand, Oslo is experiencing “land uplift” and actually shows a drop in sea level under the lowest warming scenario.

The NOC’s Domingues tells Carbon Brief that the study “exposes a deep inequity” between nations. She adds:

“This makes ambitious mitigation not just a climate necessity, but a climate-justice imperative.”

Nauels, A. et al. (2025), Multi-century global and regional sea-level rise commitments from cumulative greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-025-02452-5