Q&A: What does ‘subsidy-free’ renewables actually mean?

Simon Evans

03.27.18Recent announcements in the UK and across the rest of Europe seem to be ushering in a new era of “subsidy-free” renewables, which can be deployed without government support.

Yet “subsidy-free” is a nebulous phrase that means different things to different people. In fact, many of the “subsidy-free” schemes announced over the past 12 months would not meet the purest interpretations of the term.

While the arrival of subsidy-free renewables means zero-carbon electricity at reduced costs for consumers, it is not without challenges. Overcoming the higher cost of financing subsidy-free schemes is one hurdle; managing variable renewables on the grid is another.

Meanwhile, governments must weigh the appeal of hoping the market delivers zero-carbon electricity without policy support, against the risks of failing to meet other priorities. For the UK, this includes legally binding climate change targets.

Where are subsidy-free renewable schemes going ahead?

Last week saw the announcement of the world’s first “subsidy-free” offshore windfarm, the 750 megawatt (MW) Hollandse Kust Zuid scheme, due to be built by 2022 off the coast of the Netherlands, by Swedish state-backed utility Vattenfall.

This follows several subsidy-free German offshore windfarms agreed last year and due to start generating slightly later than the Dutch scheme, in 2024 and 2025.

The arrival in Europe of subsidy-free schemes, on a large scale, is a “revolution”, says Mateusz Wronski, head of product development for energy market research firm Aurora.

He told an audience in Oxford last week: “I think the world revolution is befitting, not just because of the sheer scale…but also because it is a marked departure from the old paradigm, where renewable deployment was driven by government intervention. This revolution brings a new paradigm, where decarbonisation can be brought about by sheer market force.”

“The last 12 months have been something of a watershed for subsidy-free schemes [in Europe],” Wronski said, pointing to planned projects announced in Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and elsewhere.

These include a 650MW onshore windfarm at Markbygden in Sweden. Set to be the largest onshore scheme in Europe, it is under construction and due to be completed by the end of 2019. In November, aluminium firm Norsk Hydro agreed to buy a fixed amount of electricity from the windfarm for 19 years.

In September, UK energy and climate minister Claire Perry opened the country’s first “subsidy-free” solar park, a 10MW project built by Anesco at Clayhill in Bedfordshire, added to an existing site.

Developer Renewable Energy Systems (RES) has planning permission to build 200MW of onshore wind and solar capacity in the UK, which it intends to develop without government support.

Meanwhile, in Spain, auctions held in 2016 and 2017 secured 9 gigawatts (GW, thousand MW) of subsidy-free capacity, mainly onshore wind and solar.

Separately, UK firm Hive Energy has planning permission for a 46MW unsubsidised solar farm in Andalucia, which it hopes to start building this spring. The firm’s 40MW subsidy-free solar farm in Hampshire has permission and is to be built this summer. It also plans a 350MW subsidy-free solar farm in Kent, though this needs planning permission and is unlikely to open before 2021.

What does subsidy-free renewables really mean?

Renewable sources of energy have been helped into the market by an array of government subsidies, tax breaks or mandates. In the UK, this has included the Non-Fossil Fuel Obligation, the Renewables Obligation, Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs) and, most recently, Contracts for Difference (CfDs).

The idea was to help renewable technologies mature through “learning-by-doing”, developing the industries, production volumes and supply chains needed to bring down costs, so that subsidies would one day become unnecessary.

In practice, this path has been far from smooth, as politics and economics have intervened, notably in the wake of the financial crisis and changes of government.

For example, investment halved after a UK government policy “reset” in 2015 ended subsidies for onshore wind and solar. The change has been particularly dramatic for solar, where only around 150 megawatts (MW) has been installed since the subsidy window closed in March 2017.

This follows a similar pattern of boom-bust cycles that have characterised the European renewables sector, as successive government subsidies have created new markets, helped drive down unit costs and then been abruptly ended.

Solar deployment has followed a boom-bust cycle in major EU economies.

(Source: BP statistical review) pic.twitter.com/W8GnMWQg0W

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) March 23, 2018

Subsidy-free deployment holds the promise of upending this cycle.

At its simplest, subsidy-free means deployment without government-mandated support in the form of the types of scheme mentioned above. So, for example, without a FiT or CfD. On this measure, almost all of the projects listed above would count as subsidy-free.

Peel back the layers on each scheme, however, and things quickly become more complicated.

Magnus Hall, CEO of Swedish state-backed utility giant Vattenfall, tells Carbon Brief what “subsidy-free” means for his firm’s Dutch offshore wind project:

“The Dutch state has set out that they will connect your windfarm at sea, but, everything else, you have to take care [of] and you also have to take the risk on [market] price development for the future. So there will be no state subsidies in terms of price stabilisation or anything.”

Regarding the grid connection, Hall says: “It’s a good way of de-risking the project. But it also means that [the project] is not fully subsidy-free, if you want to say so.” He says estimates putting the value of this connection at up to €10 per megawatt hour are “not unreasonable”. Compared to market electricity prices in the region of €45/MWh, this is not insignificant.

Still, a near-subsidy-free offshore windfarm would have been unthinkable just a couple of years ago. Hall says their costs have come down by 55-60% over the past three years as the industry has improved its logistics and deployed bigger turbines, at larger and more clustered sites. While we may already have seen the steepest cuts, there is still room for costs to fall further, he adds.

The “subsidy-free” German offshore windfarms similarly benefit from grid connections provided by government, as well as having the right to build ready-defined sites without having to manage the risk of site scoping, environmental assessment or planning permission.

Meanwhile, some subsidy-free schemes may benefit from cross-subsidisation. For example, by co-locating with projects that already have a connection to the grid or battery storage.

What about hidden subsidies?

The Spanish renewable auctions, touted by the government as offering new capacity at zero cost to the consumer, are actually underwritten with a minimum price of €21-24 per megawatt hour (MWh), according to (pdf) law firm Osborne Clarke. Though this floor may never kick in, it still helps reduce the risk faced by the projects, which could be viewed as an implicit subsidy.

In the UK, there has long been discussion around the idea a “subsidy-free” or “market stabilising” CfD. The government would still award contracts at auction, for certain schemes to go ahead, but the fixed price for electricity offered via the CfD would have to be cheaper than a reference value.

One idea, put forward by the UK government’s Committee on Climate Change, was to suggest that if renewables were cheaper than new gas-fired power stations facing the full cost of their CO2 emissions then this might arguably be considered subsidy-free. Gas is the cheapest conventional technology available, given the UK’s 2025 coal phaseout.

Alternatively, a project costing less than the market price for electricity across the lifetime of its 15-year CfD term could be considered subsidy-free. Last year, consultants Baringa Partners found that 1GW of subsidy-free onshore wind could be deployed in Scotland, if measured in this way.

A yet more stringent test would require a subsidy-free scheme to cost below the market price – currently around £50/MWh in the UK – from day one. Carbon Brief understands this latter definition is favoured by the UK Treasury.

This effectively demands that electricity from building new renewables is not only cheaper than from building new gas, but is also cheaper than from running existing gas capacity, even if this was built years ago and has long since paid off its costs of construction.

In each of these cases, the CfD offered by government would cut the risk to the renewable developer by offering a fixed price for any electricity generated. This, too, can be considered a subsidy of sorts, even if it may lead to beneficial outcomes for consumers and government.

Hugh Brennan, UK managing director for Hive Energy, tells Carbon Brief:

“What made [government] contracts work was not prices, it was a guarantee over long-term revenues. Now investors need to get comfortable with risk.”

Beyond the various measures above, there is another layer of hidden transfers of costs and risks between individual power generators, the electricity grid, consumers and government. Each of these could be considered a subsidy of one sort or another.

Fossil generators across the UK and Europe pay carbon prices that are below the cost that CO2 imposes on society, known as the social cost of carbon. From this perspective, raising CO2 prices removes hidden subsidies to the fossil fuel sector.

Another example is the UK’s capacity market, which pays power stations a fee to ensure supply is available to meet electricity demand during winter peaks. (Officially, this is thought of as a market support mechanism rather than a subsidy. But, as Tom Edwards, senior consultant at consultants Cornwall Energy, tells Carbon Brief: “If it looks like a duck…”)

Then there is the cost of integrating variable renewable output onto the grid, estimated at up to £10/MWh in the UK. Though part of this falls on the renewable generators that create it, some of the cost is shared more widely, including through the capacity market.

Aurora’s Wronski tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a system in place which is not perfect at being cost-reflective, so there are a lot of hidden and not so hidden subsidies, where costs are not passed on to those that create them…It’s probably true that everything in the electricity market is subsidised.”

Many of the costs of providing a stable electricity system around the clock and throughout the year are socialised, Wronski adds, meaning that they are spread between consumers, producers and government in some way. He tells Carbon Brief: “The true subsidy-free, if we’re being pedantic, doesn’t exist…In practice, the world is murky.”

Keith Anderson, CEO of Scottish Power, one of the UK’s ‘big six’ electricity firms and the company behind the £2.5bn 714MW East Anglia One offshore windfarm, told the Oxford conference:

“I hate that expression ‘subsidy-free renewables’. Right now in the UK, nothing is being built without subsidy, from the network to thermal generation and nuclear. So why is the renewable industry running around trying to be subsidy-free? If you think we would build a £2.5bn offshore windfarm at market risk then you are bonkers, completely bonkers. It’s just not going to happen.”

(See below for more on market risk). Tom Glover, chief commercial officer for RWE Supply and Trading, reinforced this point, saying: “I can’t build a gas station without a capacity market contract. Is it a support or a subsidy?”

The construction of Sandbank offshore windfarm. Credit: Vattenfall.

What is the potential for subsidy-free renewables?

Around 60 gigawatts (GW) of new renewable capacity could be built by 2030, without subsidy (pdf), across six northwest European countries, according to Aurora. This would make up two-fifths of total renewable deployment in the period for the UK, Germany, France, Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands, it says. In Spain, there is a pipeline of 19GW, according to another estimate.

Vattenfall’s Hall told the Oxford meeting: “In Sweden, some onshore wind would cost below €30 per megawatt hour. The question is how to bring it to market…[and] how to share risk.”

In the UK, around 4GW of subsidy-free schemes are waiting to be developed, Aurora’s Wronski says. This includes more than 1GW of solar farms that have entered the planning system after the government ended subsidies, meaning the developers can have no expectation of getting support, according to specialist website Solar Power Portal.

The Aurora estimate has drawn mixed responses, with some saying it is hopelessly pessimistic and others arguing that, on the contrary, large-scale subsidy-free deployment is a long way off.

At the optimistic end is Rachel Ruffle, managing director for UK and Ireland of Renewable Energy Systems (RES). She tells Carbon Brief:

“I was really surprised by the Aurora analysis. It seems out of touch in saying subsidy-free onshore wind will be viable in the UK by 2025. I completely disagree: it’s possible now.”

The firm has 200MW of projects with planning consent in the UK – mostly onshore wind in Scotland – and projects totalling 1GW in development. “I very much hope to close at least one project this summer,” Ruffle says. This might then take up to two years to build.

As to how much could ultimately be deployed, Ruffle says: “In some ways, the sky’s the limit – I really do believe that – because [onshore] wind is the cheapest form of generation.” RES itself hopes to deploy around 200MW per year in the UK, Ruffle says.

This sunny outlook is hardly universal, however. Cornwall Energy’s Edwards tells Carbon Brief:

“There are all sorts of reasons [subsidy-free] won’t happen overnight, though it could be possible in certain circumstances…There are some routes to market, but they’re very niche…Big projects, depending on their finance route, are not going to be able to accept the volatility inherent in taking full merchant risk.”

Merchant risk means developers earn only what the wholesale electricity market will pay, rather than having earnings secured against a government contract. It is one of the key hurdles to subsidy-free deployment, as explored in the next section.

Despite the risks, developers may have reasons to push ahead with subsidy-free schemes that go beyond pure financial considerations. For example, there may be valuable for securing future business, or for accessing favourable locations or connections to the grid, all of which are limited.

On the flip side of this non-financial equation, there is a risk that pushing the boundaries of subsidy-free deployment could erode other types of value, for example, in terms of environmental protection or community engagement.

Léonie Greene, director of advocacy and new markets for the UK’s Solar Trade Association, tells Carbon Brief she is concerned that the quality of new developments could be lost under intense cost pressure. This could mean leaving cabling above ground at a solar farm rather than burying it, for example, meaning it is not possible to graze livestock at the site.

In the case of the German and Dutch offshore bids, the winning companies get the right to build windfarms during the next five years, while their competitors have to look elsewhere. Meanwhile, they may hope that falling technology costs, changes to market rules, renewed investor interest or a combination of all three will turn just-about-viable schemes into profitable ones.

Vattenfall’s Hall plays down the idea that the bids were speculative, however. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You can see [the German subsidy-free offshore wind bids] as an option as there is a way to pay your way out of it. But if you were to choose that, it’s not only the money, it’s also reputation, it’s your future business – so it’s a big issue. I would guess that it’s not so easy [to pull out]…The types of business who do this, they are very serious.”

Hall says his own firm’s bid for subsidy-free offshore wind was based on existing turbines already on the market, rather than the even larger and more cost-effective models set to be deployed in a few years. He adds that Vattenfall is making “conservative” assumptions about future power prices (pdf).

What are the risks to subsidy-free deployment?

Many of the schemes in the subsidy-free pipeline may never get built. Companies may have secured only enough finance to get a project through the planning process, rather than to build it.

Planning decisions are another source of uncertainty, particularly for the largest schemes.

Lenders may be scared off investing when the earning potential of the project is at the mercy of the wholesale electricity market, rather than guaranteed via government contract. According to Aurora, this merchant risk (pdf) is a key challenge to subsidy-free deployment.

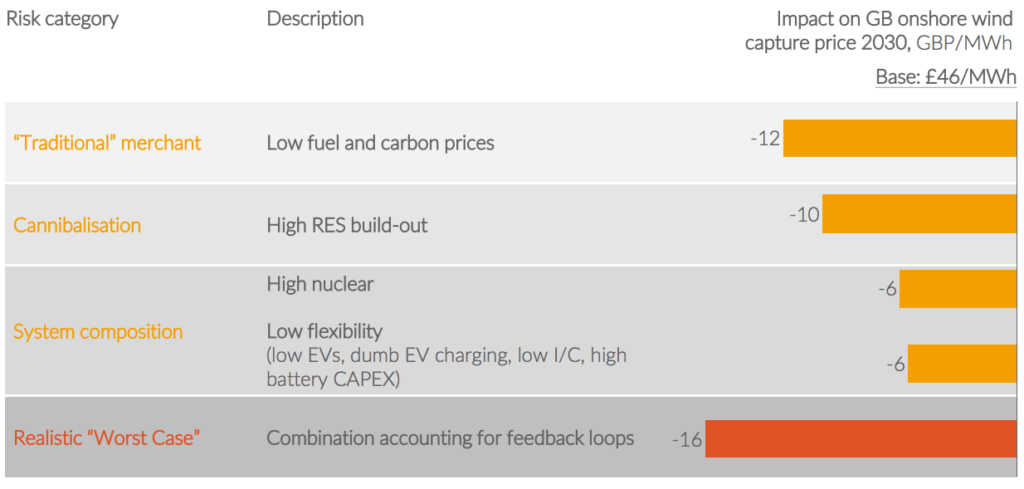

Its reference assumption is for UK wholesale electricity prices to reach £46/MWh in 2030, similar to today’s level. However, if gas is cheap and the price on CO2 emissions is low, then this could fall by £12, to £34/MWh, Aurora estimates.

In continental Europe, there is a general expectation that electricity prices will rise in the years to 2030. Yet the scale and pace of change is dependent not only fuel prices but on policy decisions ranging from when Germany decides to phase out coal power to whether EU carbon prices continue to rise, or if other countries join the Netherlands and UK in setting a floor price for CO2.

The reason this price uncertainty matters is that the cost of electricity from low-carbon sources, such as wind and solar, is heavily dependent on the cost of securing finance to build new capacity, whereas the cost of coal or gas generation depends more on fuel costs.

CfDs were introduced for precisely this reason: by fixing the earnings potential of low-carbon sources, CfDs make them more bankable investments. This means lower risk premiums and lower-cost finance from lenders.

Moving from this safe, low-risk investment environment to the riskier world of subsidy-free deployment means financiers are likely to demand higher returns to match that risk.

Gordon Edge, former policy director for wind industry group RenewableUK and now director of his own consultancy firm Inflection Point Energy, tells Carbon Brief: “Banks would not touch that kind of risk with a barge pole. Pension funds won’t do it [either].”

He thinks only private equity firms would be willing to take that risk and would demand returns of perhaps 15% to lend the money. “I fail to see how that flies, as once you load that cost of debt onto the project it gets really expensive…Someone needs to be there taking away that price risk. The best player as it stands is government.”

However, Ruffle, whose RES plans to build subsidy-free windfarms in the UK, says her “direct experience” is of lenders willing to accept “single digit” returns.

Aurora’s Wronski agrees that some investors will be willing to take lower returns: “The question is not whether there will be some capital willing to invest at 9%, the question is whether there is enough [to deploy the 60GW we identified]. We think there is.”

This uncertain volume of subsidy-free deployment has important implications for governments as they work towards the internationally agreed goal of keeping warming well-below 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, discussed in the final section, below.

What is ‘price cannibalisation’?

Another reason why financiers might shy away from investing in subsidy-free renewables is price cannibalisation. This is where, for example, plentiful solar output on sunny days floods the system and depresses the price that the solar plants earns.

As a result, “the biggest risk to renewables are renewables themselves,” says Dr Manuel Koehler, managing director of Aurora’s Berlin office.

This effect reduces the market electricity price when renewables are supplying power, known as their “capture price”. During windy or sunny periods, it makes electricity cheaper for consumers (via the “merit order effect”), but it also cuts returns for renewable developers. This effect intensifies as each new unit of wind or solar is added, setting the sector up to be a victim of its own success.

If large volumes of renewables are built in the UK, then capture prices might fall from the base case assumption of £46/MWh in 2030 to just £36/MWh, Aurora says.

A further uncertainty is that the nature of the wider electricity system has a big impact on the capture price. More flexible grids may be able to respond to sunny periods by turning up demand – by charging electric vehicles, for example – counteracting the impact of price cannibalisation.

Grid flexibility, price cannibalisation and merchant risk overlap and only partially cancel each other out, Aurora says. In combination, it puts a worst-case 2030 capture price for onshore wind at £30/MWh, a third below its base-case assumption, as the chart below shows.

Factors affecting the capture price for onshore wind in Great Britain in 2030. Source: Aurora.

How can subsidy-free schemes get off the ground?

Long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) signed between an electricity generator and a consumer – typically, a large industrial or commercial user – are one way to spread the risks of uncertain future capture prices.

However, Scottish Power’s Anderson questioned the idea that PPAs could replace government contracts to support renewable expansion. “I don’t think the market exists for PPAs to support the scale of industry we want,” he said. “It might exist in five or 10 years, but not now.”

Duncan Sinclair, partner at consultants Baringa, tells Carbon Brief that PPAs often only run for five or maybe seven years, which is not long enough to secure low-cost finance for investment. The new financing approaches needed to unlock investment in subsidy-free schemes will take a while to appear, he says: “We need a few projects to break cover. Then the market might start piling in.”

The European market for PPAs is relatively shallow, amounting to perhaps 1GW per year, says Wronski. Examples include the Norsk Hydro PPA for Swedish onshore wind, mentioned above.

This market is already expanding and there is scope for it to grow, because many large consumers could benefit from hedging their risk via PPAs. Even so, there is a limited number of firms – the likes of Google, Amazon or Ikea, perhaps – both willing and able to sign up to PPAs. Each of these firms owns only so many stores or data centres that need power.

Another option is to allow renewables to bid into a range of other markets, adding to their income from selling wholesale electricity. This so-called “revenue stacking” could advance the date for subsidy-free onshore wind and solar UK deployment by five years, Wronski says.

For example, windfarms have already shown they can provide frequency response services, helping the grid maintain electricity supplies at a steady 50Hz.

Analysis I've been doing shows how rare it is for low wind output to coincide with high demand. It seems wind can help meet the winter peak in the UK #renewables @AuroraER_Oxford pic.twitter.com/cdAFpeJDWt

— Felix Chow-Kambitsch, PhD (@FelixChowK) March 16, 2018

Revenue stacking might also see renewables allowed to bid into the UK government’s capacity market, which is designed to ensure there is enough supply to meet demand during cold, dark winter evenings. A review of the capacity market later this year may consider whether to allow this.

How do subsidy-free renewables fit into UK climate plans?

The new buzz around subsidy-free renewables comes at an interesting time for the UK, as it debates how to meet its legally binding fourth and fifth carbon budgets out to 2032.

The government’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) says current plans fall short, including in the electricity sector. It says another 50-70 terawatt hours of low-carbon generation needs to be contracted for the 2020s, in addition to current commitments for another offshore wind auction and the Hinkley C new nuclear plant. This is equivalent to 14-20% of current UK demand.

In contrast, the government’s own projections suggest there will be limited need for additional renewables. Its figures rely heavily on imported electricity to meet up to a quarter of UK demand during the 2020s, plus additional new nuclear plants, for which no contracts have been signed.

This illustrates another type of risk relating to internationally agreed (and in the UK’s case legally binding) carbon targets. The UK government could cross its fingers and assume that subsidy-free renewables will help meet those targets, but doing would constitute a risk.

“It is absolutely the case that government has a broader spectrum of risk than financials,” Aurora’s Wronski says. Vattenfall’s Hall tells Carbon Brief:

“You have to have enough players who want to go in to that [market] in order to drive that development…I’m not sure it will happen without a stabilising factor…It’s easier for a company to deploy much more capital if you have stabilising factors than if you don’t. So, in the end, it’s about attracting capital to this type of investment on a big scale…That’s why we urge governments to look at more stabilising factors, because you do want to attract a lot of capital.”

Vattenfall is one of many major energy firms active in the UK that wants the government to run a CfD auction for onshore wind and solar, even if the price is capped at the current wholesale price.

Cornwall Energy’s Edwards tells Carbon Brief:

“The consumer and developer both benefit from a stable relationship – for instance, a CfD – because it gives access to cheaper capital…There’s capital out there that wants to invest. It doesn’t necessarily need more than the wholesale price, it just needs certainty.”

However, having committed to end new subsidies for onshore wind, aim for the lowest possible energy costs and meet UK carbon targets, the ruling Conservatives are arguably caught in a political trap of their own making, where offering onshore wind CfDs appears difficult.

Politicians like to talk about the energy trilemma, RES’s Ruffle points out. This is the idea that the cost of energy, security of supply and climate change objectives have to be traded off against each other in a three-way tug-of-war. “There’s no trade off now,” Ruffle tells Carbon Brief. “The cleanest electricity is the cheapest.”

Ruffle adds: “The government says it wants the lowest cost for consumers but is also discriminating against the lowest cost generation.”

Baringa Partners’ Sinclair says the CfD framework has been extremely successful: “It’s been a revelation with CfDs just how quickly costs have come down…So it’s ironic – now we have the right policy in place, we should be reaping the benefits. Instead, government has pulled the plug.”

At Budget 2017, the chancellor opened the door to the possibility of subsidy-free government contracts, with a Treasury document published alongside his speech stating: “New [low-carbon electricity] levies may still be considered where they have a net reduction effect on bills.”

.@claireperrymp: “we will have another auction that brings forward [onshore] wind and solar, we just haven’t yet said when” (in interview with The House magazine) pic.twitter.com/eV2njR7NWZ

— Adam Vaughan (@adamvaughan_uk) March 22, 2018

The door to subsidy-free CfDs seems to have been opening wider in successive statements from Claire Perry, the UK’s energy and climate minister. In her latest comments, in a March 2018 interview with the House magazine, Perry said: “We will have another auction that brings forward wind and solar.”

-

Q&A: What does ‘subsidy-free’ renewables actually mean?

-

What is the potential for subsidy-free renewables?